Peter Hujar: The Art of Queerness

If you were to do a quick google of “cruising utopia,” the first ten results are live links to Jose Esteban Muñoz’s Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity that are either book reviews or websites to purchase the book directly. I’m not here to explicitly discuss the late Muñoz’s contribution to Queer Theory and Performance Studies. Pace Gallery’s latest staging of an online exhibition of Peter Hujar’s work spans from ’60s to the ’80s borrows the title, Cruising Utopia, from Muñoz. The title of the show gestures towards queer futurity, but do Hujar’s photographs actually match up with Muñoz's concept?

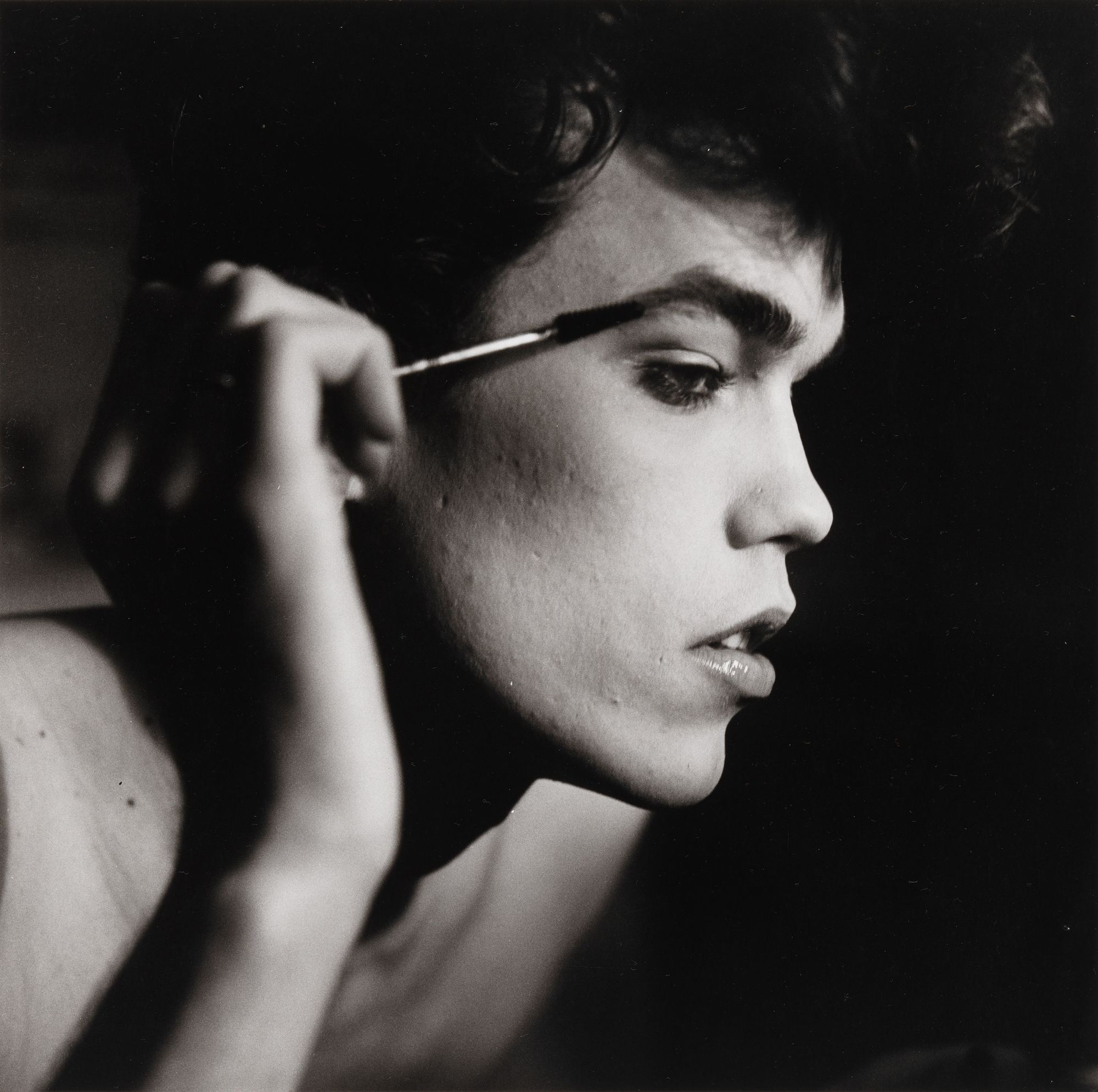

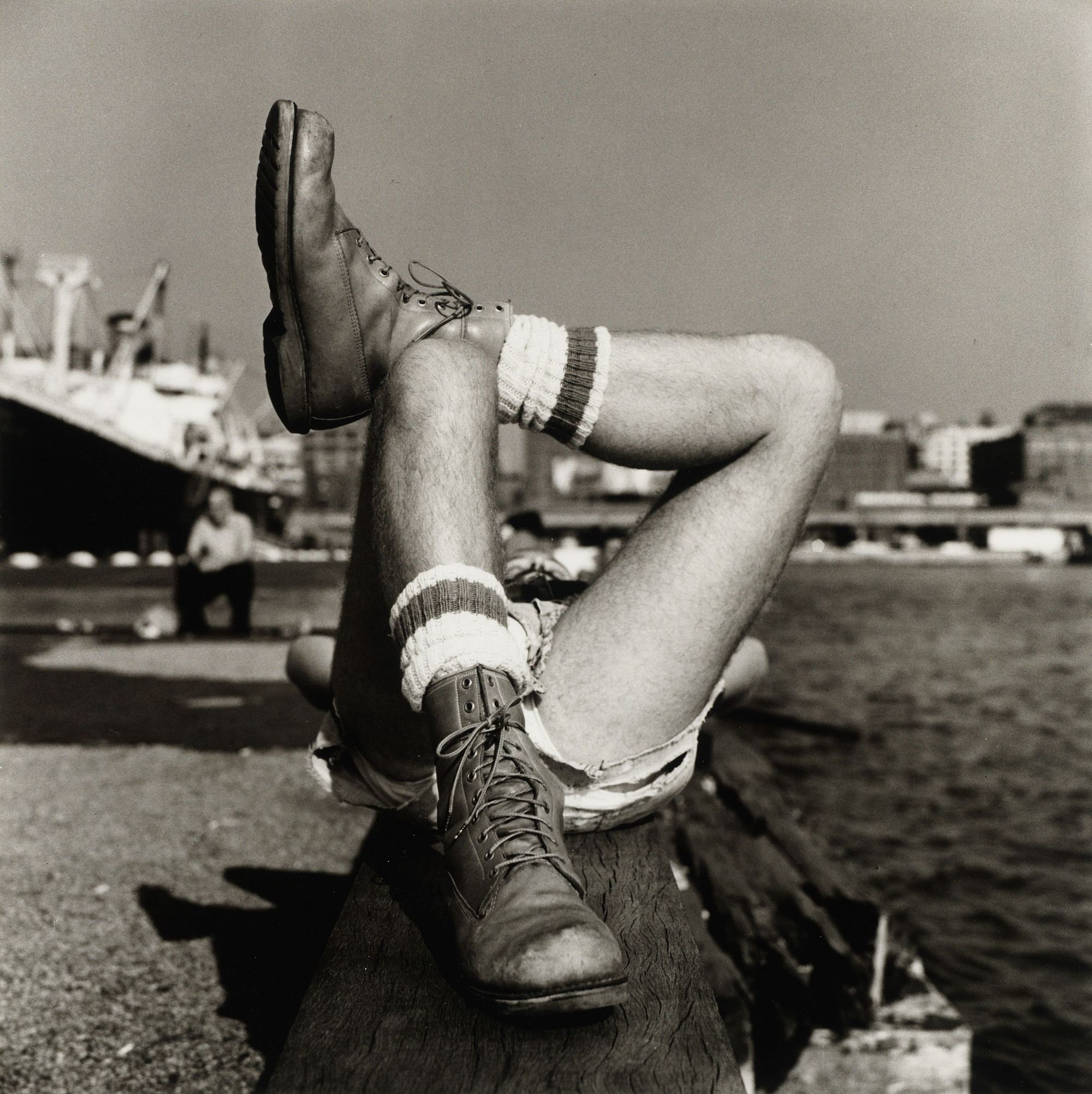

Being gay, being queer, is about more than just rainbow flags, solidarity, and the Stonewall Inn. It should be about creating and sustaining a practice of questioning, imagining, and forming new coalitions and communities beyond constructing a cohesive and legible historic account of what occured. We’re currently in this feedback loop of queerness being cosmetic, embodied through hand gestures, language, style, and memes. In Hujar’s work we see authentic accounts of what queerness could be, varying by class, identity politics, and gentrification. His work is self-effacing and doesn’t stage a certain explicit set of politics; he took stunning portraits of people who explored the limits of being a person, being gendered, and being raced. The commonalities that factor in all of those photographed by Hujar is that they had texture, depth, and a story to tell. The way in which Hujar was able to categorize and classify queerness was through details and dressing a person in a specific context, be it in a bedroom with a wallpapered background and a blanket to match the pattern; he paired knee high socks and the pier to show you where and how to cruise which locations. He didn’t have to sell you on the radical possibilities of what queerness could be but shows what it was, both as something to acknowledge as having existed in this specific iteration, not something to be embodied as an aesthetic practice. Munńoz writes, “This book offers a theory of queer futurity that is attentive to the past for the purposes of critiquing a present.” It’s hard to imagine what solidarity is now and what it should shift into moving forward.

In Feeling Utopia, the introduction of Cruising Utopia, Muñoz minces J.L. Austin’s term, felicitous speech act, where he writes, “felicitous speech acts are linguistic articulations that do something as well as say something.”

The show, Cruising Utopia, calls on us, as viewers, to imagine a different world, a place that has never existed. What are tools that are necessary to build and maintain a utopia, we’re expected to solely imagine utopian ideals but not embody or fully grasp one? Many of the people Hujar photographed suffered or died because of the Aids epidemic. The same people whose image now lives in books, archives, and galleries and the like aren’t compensated for their imagination that provides hope and context for what queerness looked like and felt like in the late '70s. These people and the movements that they created and stumbled into are useful as a way to combat discrimination and homophobia writ large. As a culture, we have sensationalized and sanitized these groundwork movements by trying to be legible to a body of people and a world order that isn’t so much concerned with our existence but with our cooperation and complacency. Marches are one way to organize a voice, but a real shift would be in organizing structures to support these creative liminal communities, to get more sustained traction and create more resources.

The photographs by Peter Hujar in the exhibition were conducted post-stonewall and pre-HIV aids movement, a moment that would come to devastate and displace a body of people who were cast aside for health concerns of the commonplace (heteronormative) people, which resulted in real estate exploitation, and the data of deaths were unreliable until 1987—the same year Hujar passed. The titling brings to mind the more controversial Benneton ad campaigns of the early ’90s that depicted: an array of colorful condoms to promote the practice of safe sex; a priest and a nun kissing in their respective garb; a newly born baby with its umbilical cord attached; an image of an interracial couple with their adopted baby; Therese Frare’s image of the late David Kirby, gay activist and aids victim, previously published in LIFE magazine as David lay on his death bed, that was originally published in black-and-white, was colored for the campaign by the artist Ann Rhoney with oil paint; an image of buttocks stamped with HIV-positive; and three identical hearts labeled: White, Black, Yellow. The Benetton photographs, to me, exercise Austin’s felicitous speech act–they incite action, conversation, and ground the moment in revealing and amplifying a useful truth and a show of them rather than Hujar might be more appropriate to title “cruising utopia”. In the midst of a pandemic, a race war, and on the tail-end of pride month, the concerns of the late '80s and early '90s are painstakingly clear today. We’re being forced to grapple with the reality of what the occupant of the White House has termed the invisible enemy, and yet again people are dying, are being killed, and displaced from their homes as we sit on the eve of what has been predicted to be the next biggest recession, because of the inaction of an administration that has failed to intervene and lead by example.

We’re familiar with the longing that lies in the eyes of Hujar’s subjects. He has choreographed and staged moments in images of places that no longer exist. When you see a Hujar photo it’s not a reality that you can recreate; it’s a distilled moment in that it not only captures the essence of what once was, but of something that can never be again. His image-work requires of us, as viewers, to reckon with the place we now call home (if you’re in New York), and that what remains in these images in large part has been forgotten–past architectural arrangements and nonexistent cityscapes. We are shown men standing, sitting, and laying at the Christopher Street Pier, both shirtless and clothed, lounging about as the day passes them by. We see a cropped image of the Hudson River water, Westside Parking Lots, a Black man, jacketed, leaning against a car at night, a white man in the midst of masturbation, an image of mainly white queers, for the Gay Liberastion Front Poster Image, who seem to be rushing towards a futurity (perhaps their own), walking shoulder-to-shoulder down the middle of a street with fists in the air; portraits of a posed Greer Lankton; relaxed Susan Sontag; Paul Thek; with Fran Lebowitz semi-nude, and a smoking David Wojnarowitz.

Currently what’s cycling my social media channels is pages specifically dedicated to funding black displaced transwomen and what’s deftly devastating for me is thinking about the necessities: food, healthcare, shelter, and housing. I’ve been thinking about how we can put systems in place so that those who are consistently producing culture are propped up and put in positions where they can live comfortably. I’m trying to imagine a utopia where it’s a sustained giving to those who are disenfranchised and either don’t and can’t play into the capitalistic production system. We’re of the mind of creating discourse around a moment or movement but have failed to construct meaningful fellowships and housing initiatives that can serve as a long term solution and better enact allyship. What I’ve noticed over the past few weeks as we’ve reckoned with the moral and social politics of the workforce, the shuddering and removal of the mostly white presidents, CEOs, and founders of companies, these same people have come out of the woodwork and completely copted the language of those disenfranchised to perform a respectability politic that doesn’t fully rectify the everlasting impacts of their inaction or willful ignorance.

To imagine a utopia, to claim a utopia, we have to ask for more and stop at nothing. To be sold our rights, to reason with empty gestures by corporations and institutions and the like is to stage an aestheticized politic that isn’t so much radical as it is a prop of desire many people are willing to claim as their personal politic but fail to practice in their day-to-day lives as a commitment to be better and do better by those less fortunate than themselves. We’re nostalgic for a time that never existed, hungry for a freedom we must stake and claim for ourselves on our own terms. We can’t cruise a utopia we must demand and enact it.

Subscribe to Broadcast