Perpetual Motion

I first saw The Great Wave off Kanagawa (1830-1832) by Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) ten years ago during his first retrospective in Europe at Berlin’s Martin-Gropius-Bau. I had to line up early on closing day to see an exhibition that was always packed. I saw the print again this year at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Unlike my first encounter with the work, I didn’t plan to see it and there was no line to enter the gallery. During the intervening years a great deal had changed, not only in the public’s habit of museum-going, but more generally in the state of the world, and also in my life. But whatever these changes might be, there are strangely enough similarities that remain between now and Hokusai’s time.

The great Japanese printmaker chronicled life in Japan during the Edo Period (1615-1868) and part of why his prints remain popular is their ability to remind audiences that someone from the past had similar experiences. The Thirty-six Views, of which The Great Wave was part, were made when Hokusai was in his seventies, both as a response to a domestic travel boom and as part of a personal obsession with Mount Fuji. Although he had a prosperous middle age, a series of setbacks—intermittent paralysis and the death of his second wife—left him in financial straits in his later years. In The Great Wave, the sea takes on the shape of an eagle’s talons about to devour the men clumped on one end of their kayaks. Mt. Fuji is a small figure in the middle of the composition, a perfect cone that punctuates the horizon, symbolizing serenity that contrasts with the chaos in the foreground. It was this work that secured Hokusai’s international fame and is said to have inspired Debussy’s La Mer (1905) and Rilke’s Der Berg (1906-1907).

The enthusiastic reception of his works at Martin-Gropius-Bau came just four months after a whopping magnitude 9.0 earthquake struck Japan in 2011. It was the fourth most powerful earthquake in the world since modern record-keeping began in 1900, and it triggered powerful tsunami waves, similar to those depicted by Hokusai, that reached up to 133 feet in Miyako in Tōhoku’s Iwate Prefecture. Its strength was such that the earthquake shifted the earth on its axis and the tsunami that followed ended the lives of nearly 20,000 people.

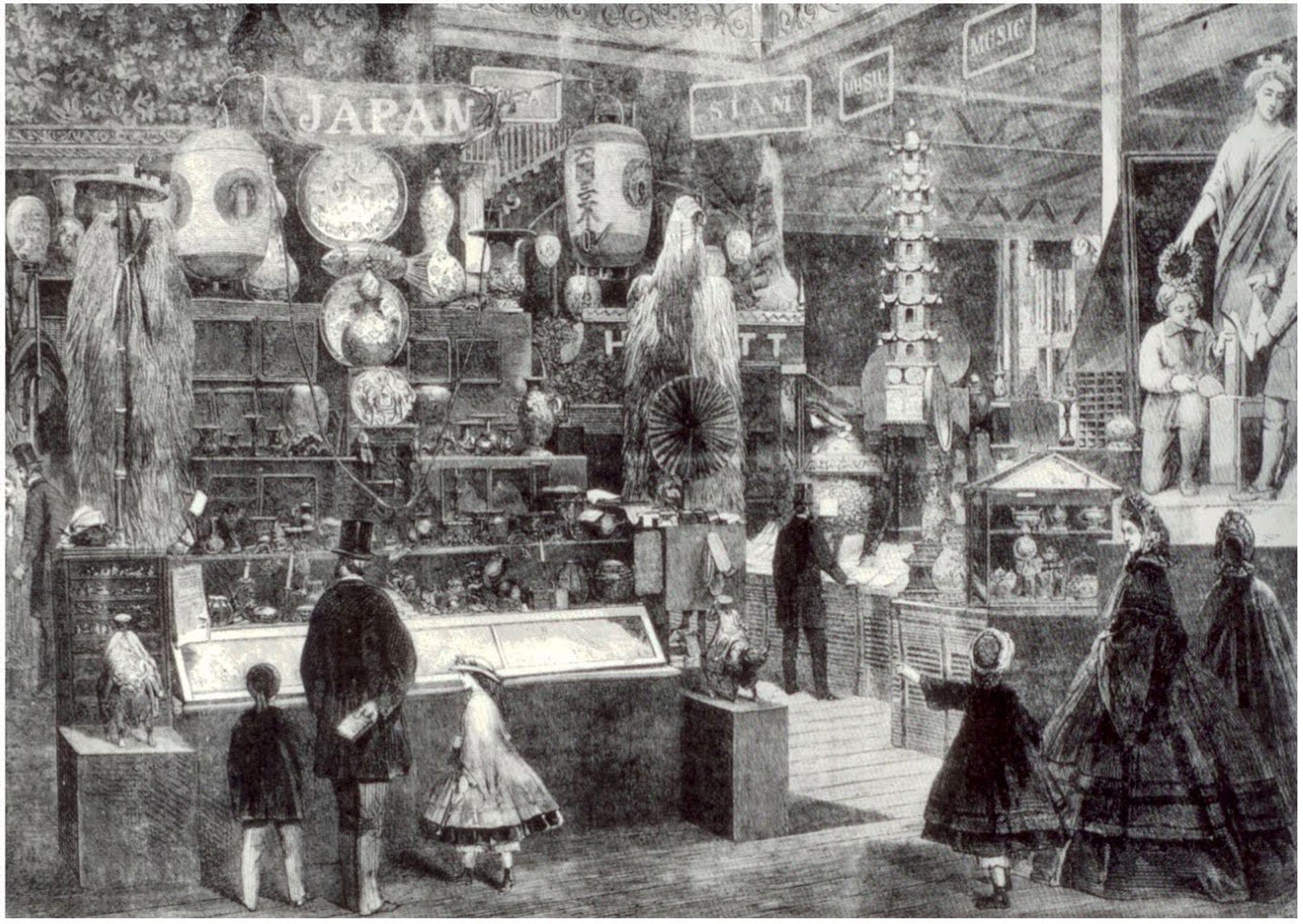

With Hokusai’s sustained popularity and with the staggering commercial viability of Asian contemporary art, it’s hard to imagine that before Hokusai’s prints reached Europe, Japan went through two centuries of isolation. If not for a small window opened to the West via the Dutch trading outpost of Deshima outside Nagasaki in the early 19th century, we would not have learned of Japan’s art and crafts until much later. Through Japan’s participation in World’s Fairs in 1862 in London, 1867 in Paris, and 1873 in Vienna, Western obsession with its arts and crafts grew exponentially.

Up until Hokusai’s exhibition in these fairs, most of his woodblock prints in Europe remained in private collections. Philipp Franz von Siebold, a German doctor, was one of the few specialists of woodblock prints from Deshima. His collection was opened to the public in Leiden in 1837, but it would take three more decades before the brothers Edmond and Jules de Goncourt visited his collection and wrote a monograph which started the ripple of “Japonisme,” a cultural wave that conquered bourgeois Paris in the nineteenth century.

Unknown to early admirers of Hokusai’s works, the colors that he used were imported from the West. The dominant color in these prints was Prussian blue—also called Berlin blue—which was introduced by the Dutch to Japanese printmakers around 1820. The synthetic process of making the pigment lowered the price enough that the shade of blue became feasible to use in prints for the first time.

Hokusai’s talent in retaining detail despite the uneven pressure he placed on the paper sheets is another intriguing characteristic of his prints. His process is more about rubbing than pressing the plate on the paper. The pressure is manually applied and not—as with his counterparts in Scandinavia at that time—with the iron press. The result of this technique can be appreciated in the delicate lines of the nets in Kajikazawa in Kai Province (Kōshū Kajikazawa) (1830-1832), another print series in the Thirty-six views, or the sea spray from Choshi in Shimosa Province (Shoshu Choshi) (1833-1834), and in the delicate pictures of flowers and birds, such as in Hydrangeas with Swallows (1830-1834).

The aspects and variations of the views of Kanagawa that I witnessed in the Hokusai retrospective seemed limitless given the fact that he worked with traditional tools and rare color options. I left inspired by a collection of thoughts about humanity’s relationship with nature that was both beautiful and punishing. This is a theme that persistently appears in Hokusai’s work; human gestures and their depicted facial appearances reveal deeper narratives about Japanese animistic culture. They also comment profoundly on the precariousness of humanity in the face of nature’s wrath.

Lost in the barrage of news about the COVID-19 pandemic was the resurfacing of Hokusai’s drawings from the British Museum, which included Shikinamigusa or Waves of Potential Immigrants from Many Lands (1796) last seen in 1948 during an auction in Paris. The collection of drawings include an array of subjects: playful cats, serene landscapes, even severed heads such as the one depicted below.

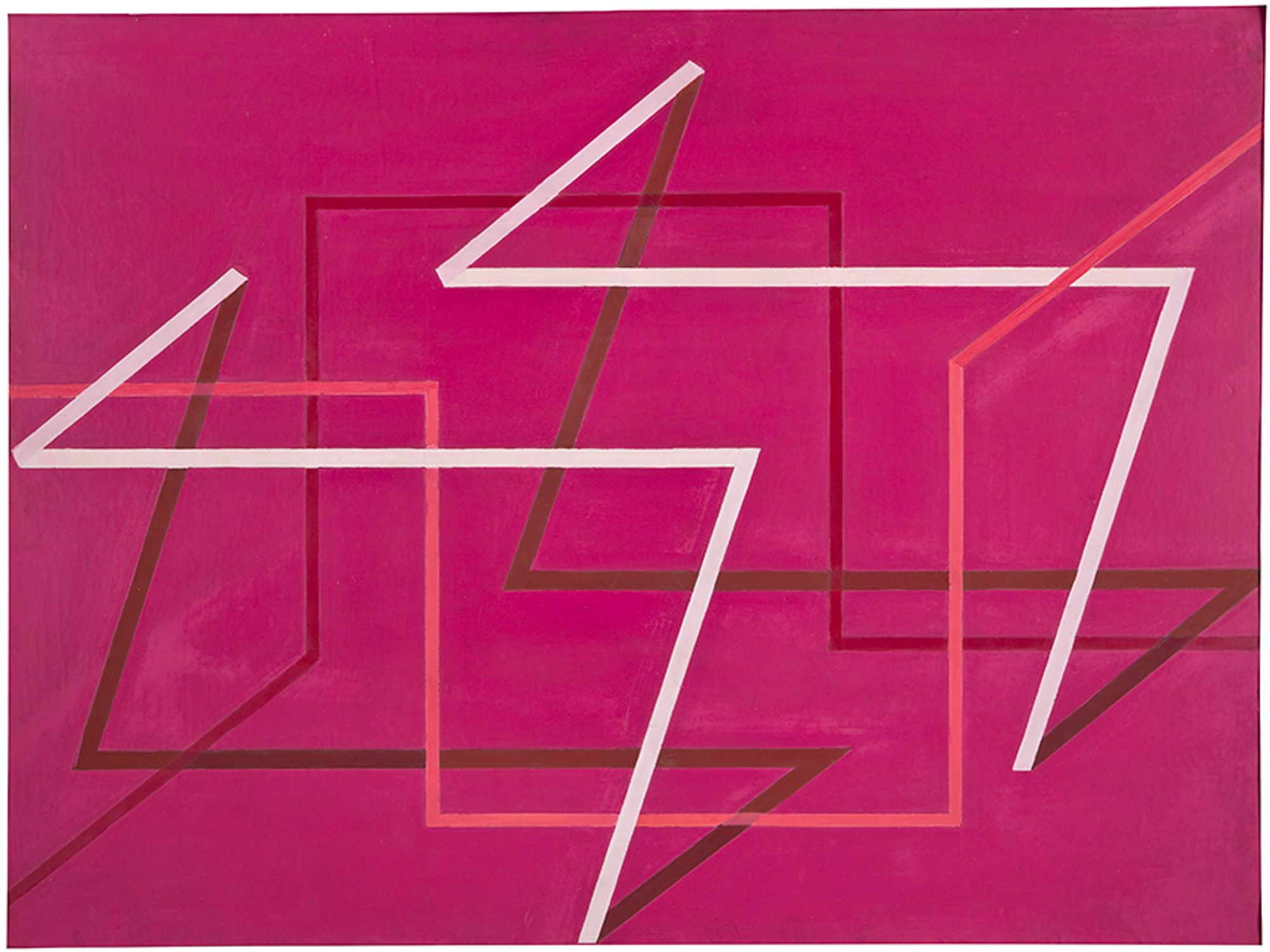

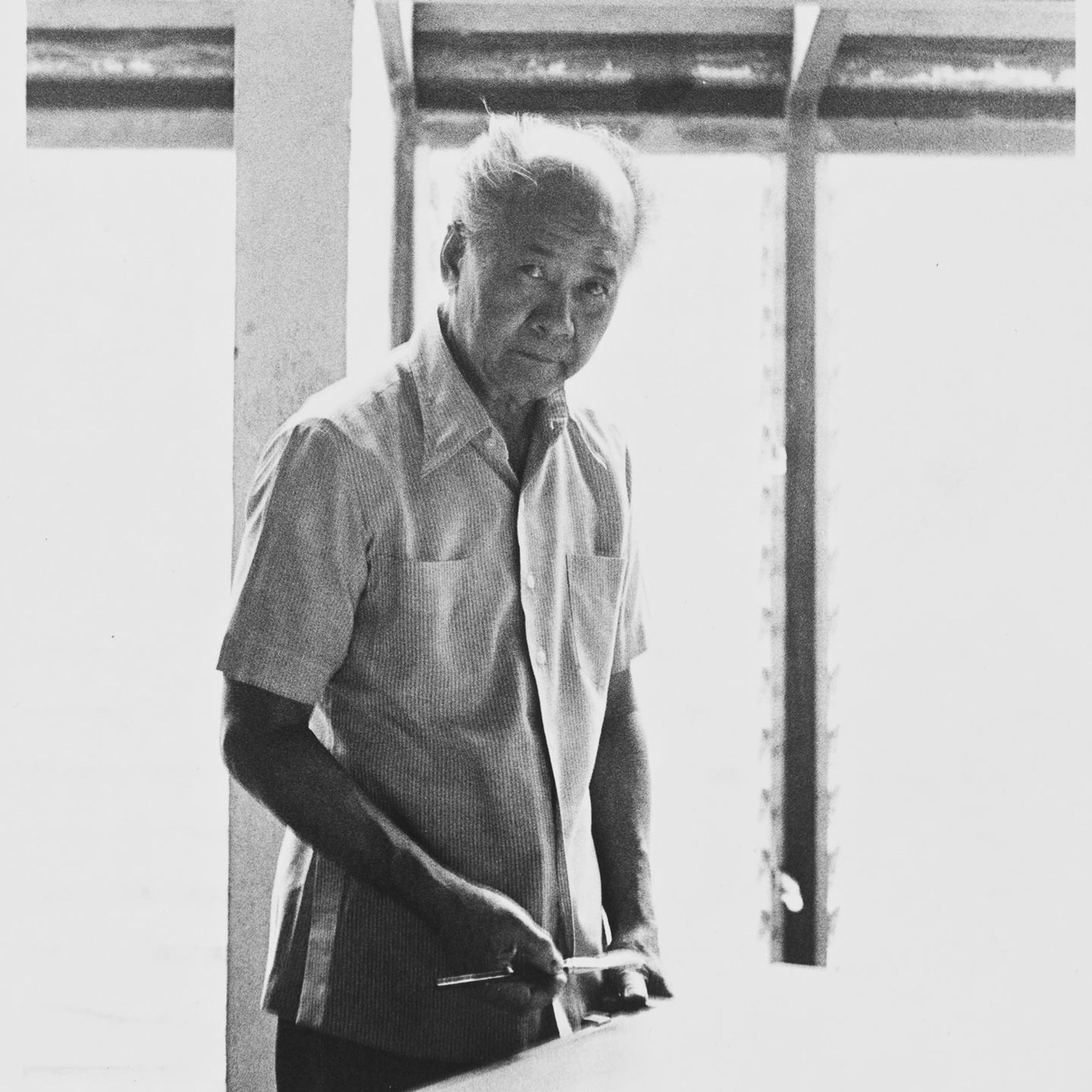

Reflecting on the work of Hokusai amidst lockdown led me to comparisons with a Filipino artist who is the main protagonist of my research on Southeast Asian Modernism. Like Hokusai, Constancio Bernardo (1913-2003) lived and worked in an archipelagic country and his long career in the arts was often punctured by tragic events and personal loss. Born on December 22, 1913 in American-occupied Philippines, Bernardo was originally trained as a figurative painter under the colonial academy, but he turned to abstraction after being mentored by Bauhaus veteran and German immigrant Josef Albers at the Yale School of Art in the 1950s. Bernardo thoroughly internalized Albers' teaching within a brief but intense period from 1948 to 1952, culminating in his painting Perpetual Motion, the centerpiece of his Master’s thesis

In the painting, a horizontal rectangle of thinly applied red paint is animated by bold white lines that form acute angles and are overlaid with bold blue diagonal lines. The lines create illusions of depth through the suggestion of recession and of shadows. Thinner lines add to the geometric complexity, suggesting axiomatically rendered rooms and portals. Cubic volumes interchangeably recede and protrude—space yields to volume, mass dissolves into

Rather modest in size and stark in composition, nobody knew the pioneering significance of the painting during Bernardo’s lifetime. Albers is said to have sat for hours on end studying this painting and told Bernardo, “You are not my student; you are my

Bernardo’s artistic training, which involved finding not only his signature in art but also his identity, finds parallel in the life of Hokusai. Both were fishermen and created works about life in their fishing villages. After years of training as an apprentice for a woodblock printing workshop, Hokusai entered the studio of Katsukawa Shunshō at the age of eighteen. Shunshō was an artist of ukiyo-e, a style of woodblock prints and paintings that Hokusai would master, and head of the so-called Katsukawa school. Ukiyo-e, as practised by artists like Shunshō, focused on images of the courtesans (bijin-ga) and kabuki actors (yakusha-e) who were popular in Japan’s cities at the time. After a year, Hokusai's name changed for the first time, when he was dubbed Shunrō by his master. It was under this name that he published his first prints, a series of pictures of kabuki actors, in 1779.

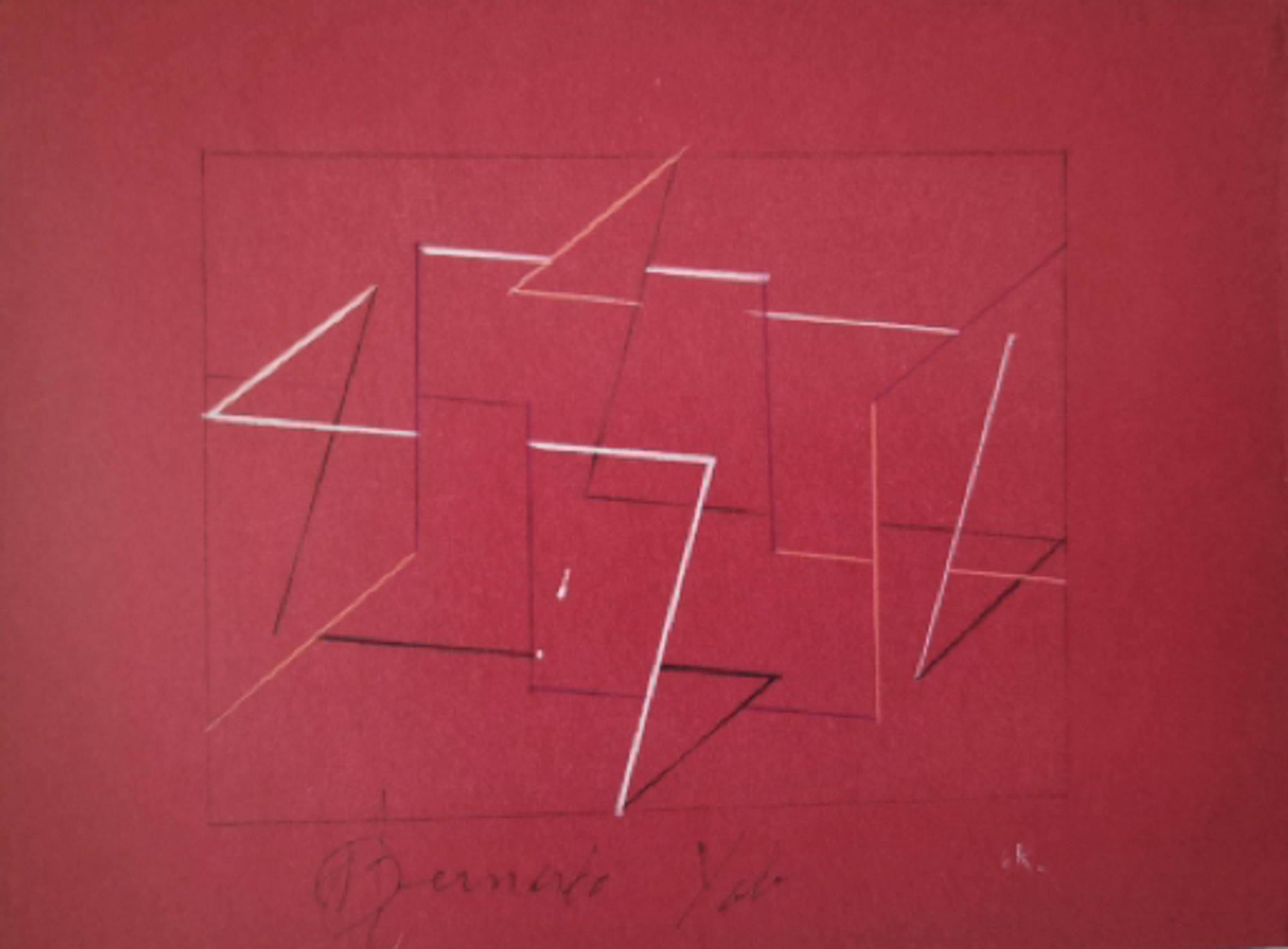

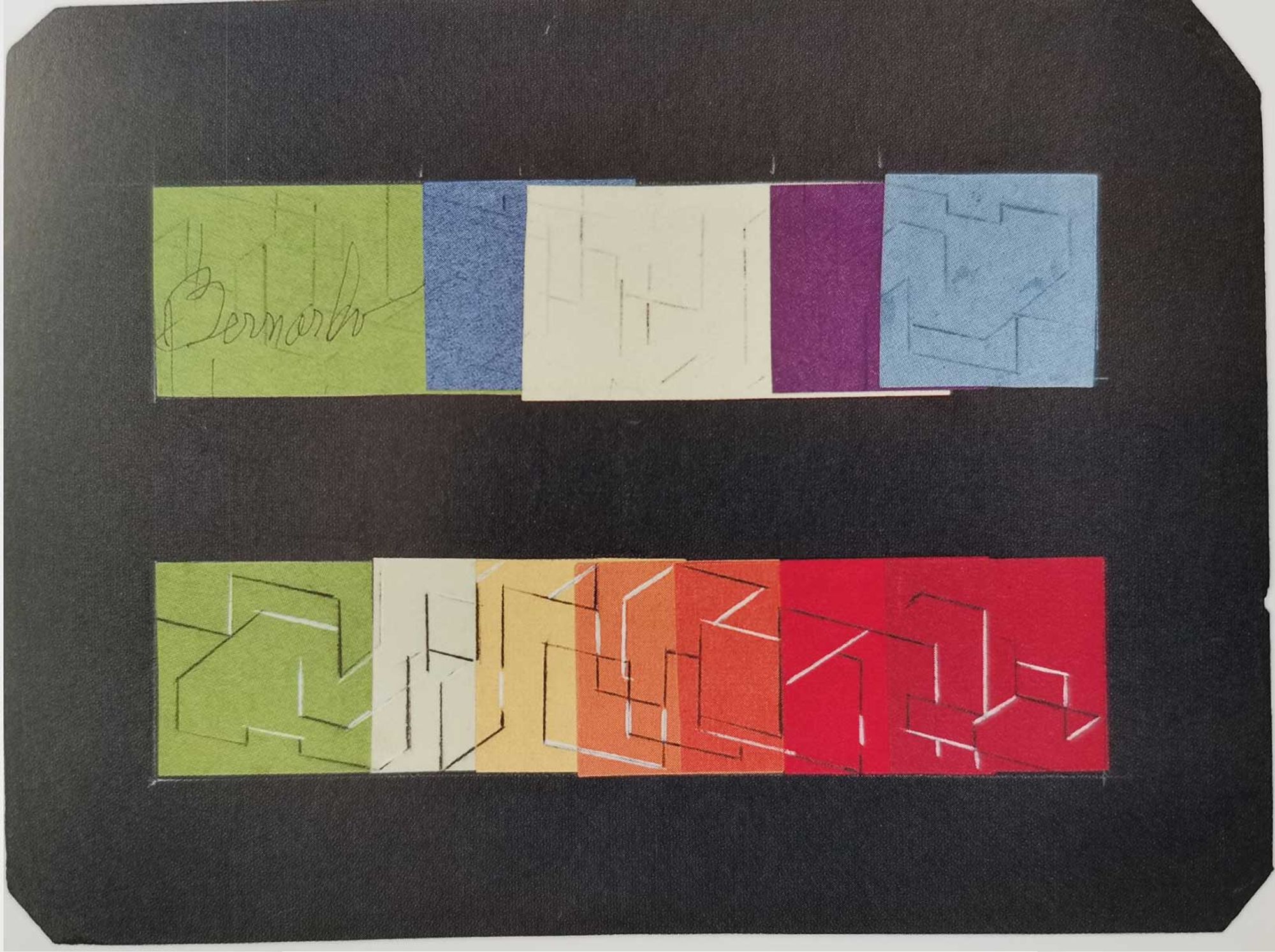

Like Hokusai, Bernardo started painting from an early age, initially as a self-taught artist. He was mentored by academic painter Fernando Amorsolo as an undergraduate student in the University of the Philippines School of Fine Arts in Manila. He was in his early thirties when he enrolled for an MFA at Yale and was mentored by Albers. The elegance of Perpetual Motion could not have been achieved without the hundred abstraction studies Bernardo had made before his thesis exhibition. Extant examples of these studies show improvisations on the horizontal rectangular format, a monochromatic ground (red, blue or purple), and abstract linear compositions that explore the tectonic and kinetic possibilities of angular lines or “inclined planes that seem to bounce off the edges within prescribed

In the preparatory version of Perpetual Motion (a 20 X 27 cm version, 1952), two stacked horizontal color bars overlaid with black and white lines evoke a schematic cityscape. Bernardo’s multiple studies were made shortly after Albers’s first linear Structural Constellations in 1949. Both artists were exploring volume shifts and vibrating forms through linear constructions. This exploration did not merely involve sitting in front of a canvas and waiting for inspiration. The process was physical and performative, and Albers, who found gestures more effective than words, often asked his students to get on their feet and follow his movements.

Hokusai and Bernardo understood movement. For them, mobility was more than just a creative act, it was a response to life’s circumstances. Hokusai relocated ninety-three times due to floods and earthquakes. He lost his studio to a fire at the age of seventy-nine. Despite the neatness of his prints and his impeccable drafting skills, he often worked in derelict places filled with dirt and grime. He was so averse to the task of cleaning that when the floods came in and coated his works with mud, he preferred to move to another studio. Hokusai not only abandoned places but also identities as evidenced by his difficulty settling on a single name. He went by more than thirty, each one associated with a specific period of his career. The name on his tombstone signaled an undiminished energy to continue creating: “Gakyo Rojin Manji,” which translates to “Old Man Mad about Painting.”

Bernardo, too, had to relocate his practice a number of times in the face of war and political turmoil. When the Second World War erupted he moved his family to the rural enclave of Obando, the countryside of his youth, and when dictator Ferdinand Marcos assumed the presidency [of the Philippines] in 1965, he moved his studio deep into the forested campus of Diliman and then in Baguio, away from the glitzy urban art scene in order to continue making art.

When Bernardo began graduate studies at the Yale School of Art in 1948, he planned to study only for a few months but he ended up staying for four years. The long sojourn made him feel profoundly disconnected from his origins in the Philippines and the life he led there as a US colonial subject, an apprentice to his professors, a husband, and a father. Bernardo would emerge from his encounter with the mainland of American and training under Albers as a completely modern man. Albers, too, retreated to his hometown of Bottrop during the First World War and lived in Weimar and Dessau before migrating to the United States. For Hokusai, Bernardo, and Albers, then, movement and beginning anew in new milieus informed their respective takes on modern art.

From Hokusai and Bernardo I learned how painting is a distilling of experiences in the world. Through Hokusai I was able to see an image of our current selves through the lens of the past, and how nature can be a mirror to our world of machines and skyscrapers, one that nonetheless always threatens to wipe out our existence on this earth. Through Bernardo’s Perpetual Motion, I noticed how it isn’t the shape or the colors that is the real subject of the painting, but the vibrations of our vision, the feeling of transience, of things observed and caught between the interaction of color. Bernardo did not paint a specific image, but rather an echo of sensations we may recognize: namely, mourning and grief. He painted them as forms that never seem to sit still, or as reflections. The forms seem edged in blue like a shadow, or like the leading of a stained glass window.

Both Hokusai and Bernardo’s pictures have a habit of looking different after you've peered closely at key details. The parts begin to fit together. For example, the lines in Perpetual Motion suggest a split horizon as if the frames have been caught in an instant, a momentary gift of light. The brushwork and colors strangely remind me of the delicacy of the tense scenes depicted in Hokusai. Once reminded of the birdlike qualities of The Great Wave, Perpetual Motion's abstract lines are evocative of waves, of light, of falling water. And always a sureness of tough, swift, supple fracture.

Bernardo’s earlier sketches, particularly his Death March Study (1942-1943), which depicts the Japanese cavalry on a murder spree in the Philippines during World War II, remind me of the Shesun landscape jottings. Rapid lines follow the trail of a shadow. They have a calligraphic quality, just bold guidelines steering the eye, keeping the eye restless, like a sudden change in the wind. Or tracks, half lost in the sand. They’re wonderfully subtle and evocative despite the violence of the scene depicted.

Bernardo’s turn to abstraction was carried out during the flood tide of American action painting; it has all the wild vigor of that hectic era. His Perpetual Motion seemed as though it was reacting against too much gesture, like it was completed overnight with a yardstick on one hand and a great sweeping brush in the other. In fact, it took Bernardo eighteen months of agony, grieving over the loss of his youngest son whose funeral he could not attend because he could not afford a return trip home.

He tried to figure out the ideal composition through numerous drawings, as well as six different versions of the painting. At one stage, Bernardo became so disillusioned that he almost abandoned the project. When Albers later inquired about the work, Bernardo took the canvas out of storage and suddenly felt encouraged to continue. This time there was balance between line and color. In May 1952 the finished painting was exhibited, and Albers predicted an auspicious career for Bernardo: “When you return to Manila, you will create an explosion in art.” But when it was exhibited in Manila the following year, it was panned by critics. The painting sat in storage for another seventy-fve years before it was rediscovered and recognized as the first example of modern abstract painting in Southeast Asia.

The painting has become a talisman for the uneven development of abstract art in the Philippines. People didn’t understand it. In the 1960s, the art critic Leonides Benesa labelled Bernardo the “Father of Philippine and the title sat uneasily on his shoulders. His geometric abstraction masks a thoughtful and reflective man. At Yale, he was also trained by Willem de Kooning and he personally saw how the so-called action painter didn’t come up with paintings instantly but reworked an image a hundred times.

Light and energy rush into Bernardo’s paintings, bleaching the colors, dispersing forms until only a few disconnected shapes survive. It's curious how light, which enables us to detect the smallest details in everyday objects, so often in art melts or obscures those very details. Bernardo is an artist who reduces, who eliminates the longer he looks. And this reductionist vision is one he shares with earlier masters of landscape, who in old age discover light to be an obsession: Turner, Cezanne, Monet, Matisse. The lines begin to grow as familiar as zips of flight or light at the end of a tunnel, the colors float just as these do among fields of red. There’s no need for a figure or a literal visualization of movement, just the gulf between abstract and representational painting, which Bernardo bridged with a leap of his imagination.

Just as Bernardo’s journey to Yale had been decades in the making with the specter of war framing its twists and turns, so too was Albers’ journey to Yale similarly overdetermined by war and displacement.

In 1915, while many of his friends and classmates were marching off to the Great War, Albers returned to his hometown to become a primary school teacher. He had just spent two years at the Royal School of Art in Berlin (Königliche Kunstschule zu Berlin) and had tried to get into military service, but he was rejected because of a lingering lung condition. Prophetic of the impact that Albers would make in art education, the primary school bore his name: Josefschule. Born on March 19, the feast day of Saint Joseph, patron of laborers, in 1888, Albers was baptized according to Catholic custom of naming babies based on a calendar. During those years, Bottrop was a boom town in the Ruhr mining industry. Albers recalled in an interview, at eighty years old, that the town was “uncomfortably ugly—except at night when you were sitting on the train and the lights of the mines and factories looked like

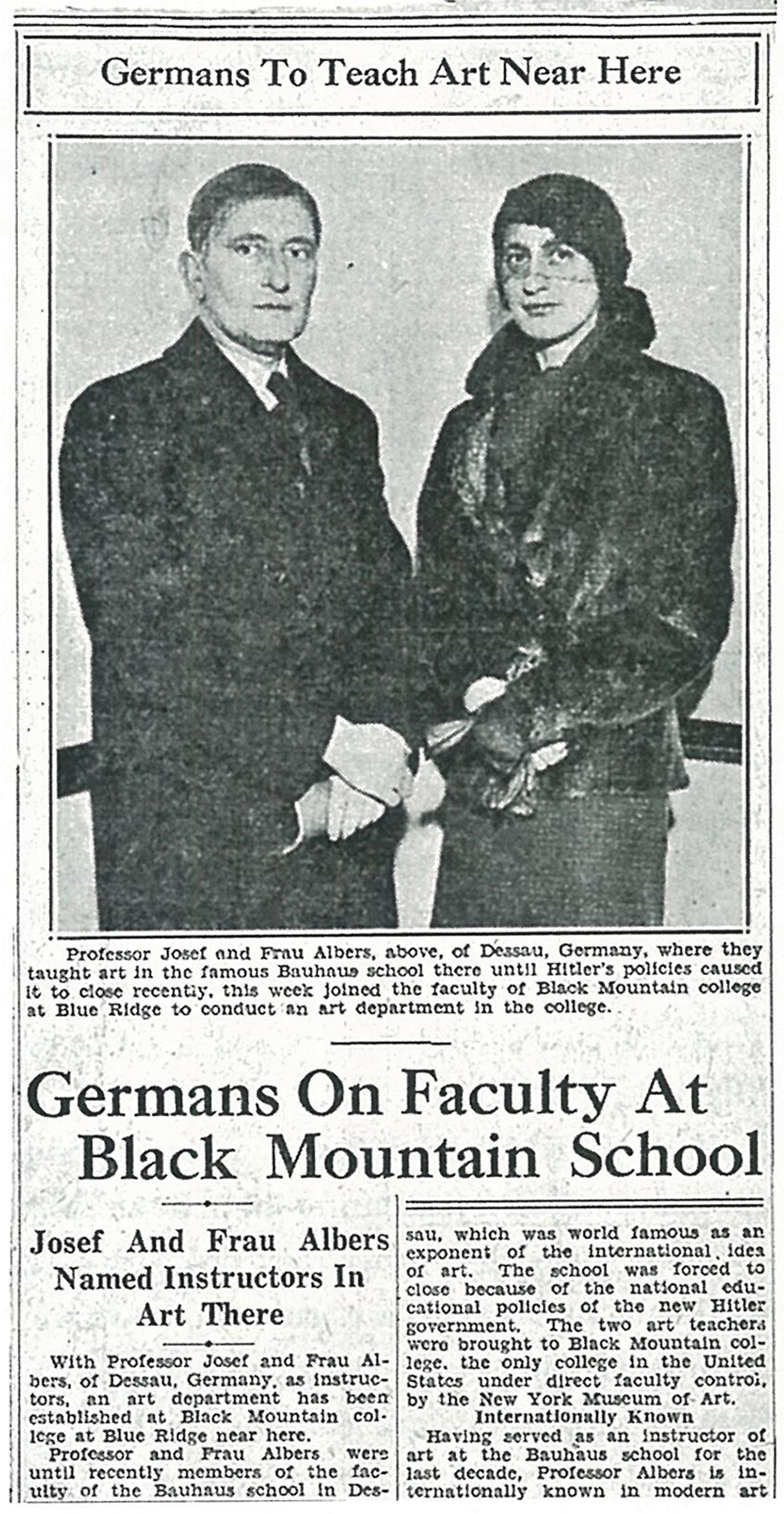

A few years later, Albers moved to Weimar to join the Bauhaus, then the world’s most renowned art school. He arrived as a student and eventually became Meister of the Foundation course and head of the glass workshop. The son of a painter and decorator, he fell in love and married Annelise Fleischmann, a rich Jewish girl who worked in the textile workshop, thereafter known as Anni Albers. In 1933, when Nazi pressure forced the German Bauhaus to close, the couple took jobs at Black Mountain College, which had thirty students, was six months old, and in the “back of beyond and completely unknown.” It had no art department. Having never left Europe, the couple took an atlas and desperately tried to find North Carolina on the map of the Philippines, which was then a transit point for Jewish refugees to the United

Art historian Eva Diaz has written about the anti-German sentiment that arose when Albers and his wife Anni were hired to teach at Black Mountain. She cites a news clipping from North Carolina’s Asheville Citizen on December 5, 1933, which read, “‘Germans to Teach Art Near Here,’ adding, though ‘Fresh off the Boat’ would do just as well.” Diaz describes that the Albers couple “posed tensely in formal attire: he in tie and jacket, she in fur, cloche, and veil. Tightly angled in a corner, they look very much like the anxious, recent immigrants. While Anni's mild gaze seeks out the viewer, Josef averts his eyes, his stiff bearing and tightly clasped hands registering trepidation, even

Bernardo’s concern in his MFA thesis was the search for the Absolute in “pure abstraction,” and his approach often conflated metaphysical and religious experience. Bernardo found an affinity with Albers’ Catholicism. Being both foreigners to the U.S., their religion became their common language. Albers was born and raised a Catholic and throughout his life he regularly attended Sunday mass and went to confession. New studies on his have drawn attention to his religious upbringing as well as his admiration for the masters of early Christian art and Albers encouraged Bernardo to distill the spiritual and to learn to express the personal and psychological components of his associative abstract paintings through the repetition of form and color.

Bernardo’s turn to spirituality was in part an attempt to cope with the death of his third son back in According to Carina Evangelista, Bernardo was “caught in the whirlwind of radical, exciting change in American modern art and denied the comfort of the familiar in either home or family, Bernardo held strongly to his faith as an anchor in the face of devastating

From Albers, Bernardo learned many enduring lessons, including the need to see a “present free from the dominant influences and conditions of the Bernardo wrote about “the effect of conflict upon the the notion that “every great idea leaves behind it a certain amount of latent He learned that “traditions and conventions can be too overgrown that they hamper progress.” More than Albers’ technical demonstrations, it was through his imparting of the possibilities in abstract painting that Bernardo was converted from figurative painting to geometric abstraction. His Master’s thesis went on to explore how abstract painting can create poetry and enable spiritual Perpetual Motion alluded to the movement of vision through the interaction of line and color and to the metaphorical transition from figuration to abstraction, and to the crossing of borders between earthly places, and the physical and spiritual world. Bernardo said in an interview that he saw “a flaw in extreme allegiance to the physical and suggested that we don’t give enough attention to what only the mind This parallels a 1968 interview where Albers stated, “I make you see more than there is ... Absolutely something

Albers and Bernardo shared the process-oriented, material-based mode of instruction that constituted a major aspect of the Bauhaus Vorkurs, which was key to Bernardo’s experimentation with unconventional materials. On the surface, Albers gave practical advice to Bernardo to help him understand color, but the advice conveyed a deeper understanding of what it means to see and create art.

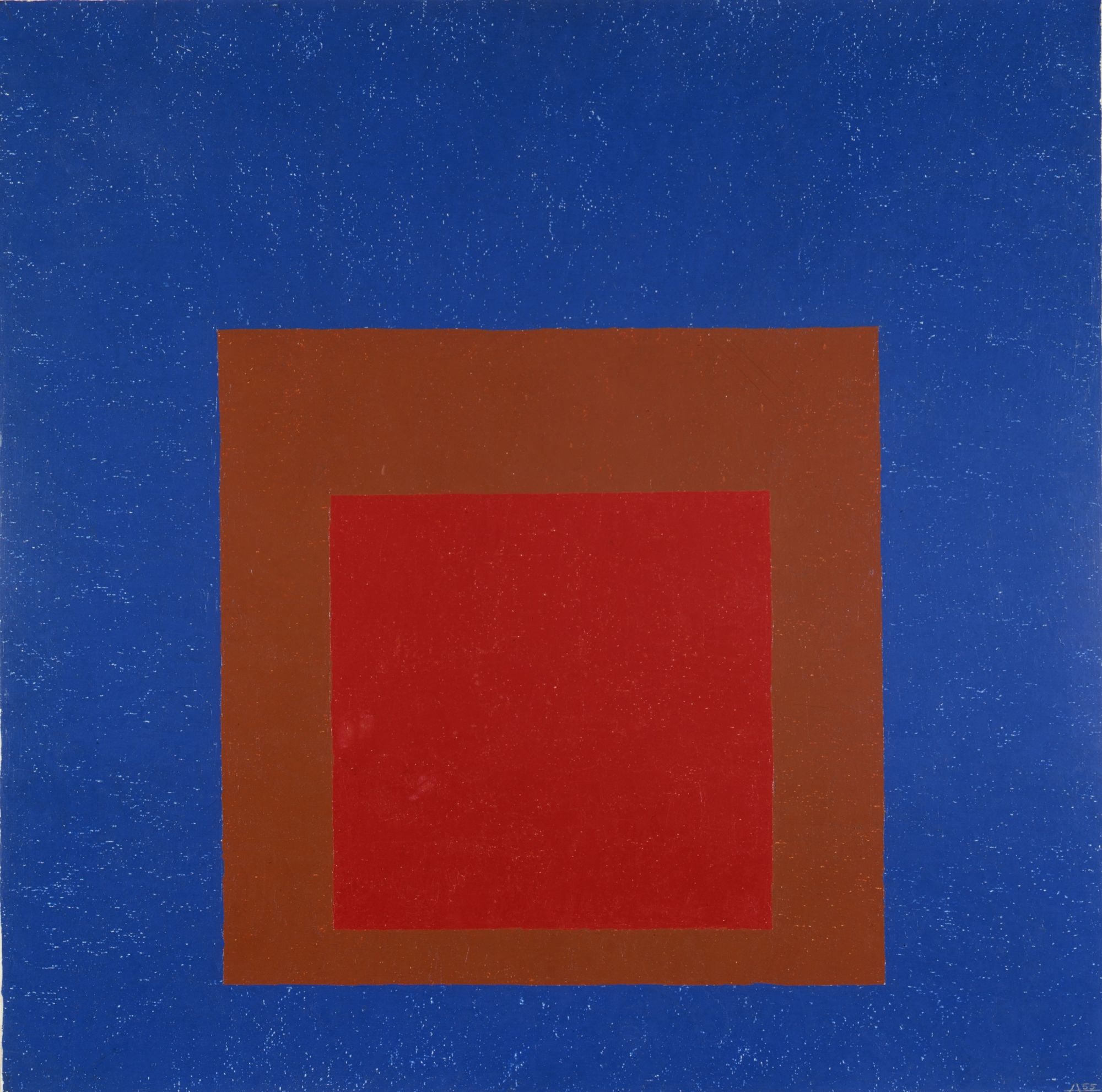

In calling this picture Against Deep Blue (1955), Albers alluded to the color of a flawless summer sky and its reflection in deep water. “My painting is meditative and peaceful,” Albers once said, “and that's what I’m aiming for, images to help meditation in the 20th century."

In Bernardian Synthesis No. 1, a 1978 triptych, Bernardo distills an environment. Even looking at it briefly, one is aware of depth, light, and movement. Nothing is superfluous. Between the simple colors—orange, yellow—lie rarer in-between hues. Shadows track the surface like a skater across ice.

Albers’ pedagogy enabled students to see what modern art is all about: vision and responding to the reality of the times. Albers cast off the established rubrics in arts education that blinkered the imagination of his students, initiating them into the principles of modern art as it was taught in the Bauhaus. Albers was the migrant who turned out to be the ideal teacher to give lessons on the unbounded power of Modernism in shaping pioneering artistic practices.

Hokusai, Bernardo, and Albers’ artistic practices make me reflect on the ethics of making art as humanity today faces death from a microscopic pathogen. They show us another direction from the aestheticization of pain and suffering, as they avoided romanticizing disaster and isolation as creative impetus.

I thought of this when, around the same time last year, an infection recurred from a virus I had contracted earlier while traveling around Indonesia, a less aggressive cousin of COVID-19. My lungs had collapsed, functioning at only ten percent, or so it seemed from the luminous network of roots in the chest x-ray taken at the hospital. On top of that, my gallbladder and my appendix were infected and had to be removed. Completely immobilized and unable to breathe, eat, and defecate, my body contorted like a voodoo doll before I was injected with tranquilizers. The surgical operation took four hours through four holes in my chest and abdomen. When I woke up, I was stitched up and wrapped in what looked to be a tin foil blanket that emitted steam. Intubated and wired to a drip, I imagined feeling the weight of my three-month old baby in my arms, but when I opened my eyes I saw no one but an orderly hovering over my gurney.

It took me two weeks to recover at the hospital, where I was grouped with four other patients. We couldn’t talk and visiting hours were limited. For most of the time I was alone, exercising my lungs with a plastic toy the doctors had given me. I was told that I could only be discharged when I was able to lift two balls in a tube with my breath, and hold it in the top position. There was nothing to feel but the brokenness of the body, how the flesh and organs could easily feel fragmented by disease.

Since my daughter was born around the time I was quarantined, I couldn’t see or carry her in my arms. I could only interact with her through a wall of glass. Yet the unexperienced sensation of carrying her was the signal that woke me up and reminded me that I was still alive. I have been separated from my daughter for two years now since I moved to New York, except for a brief two weeks during the holidays when I had a taste of becoming a stay-at-home parent: giving her a bath, preparing milk through intermittent sleep, and endless games to encourage her to walk and speak.

Just as I was revisiting The Great Wave at the Met, I heard the news of a strong typhoon called Ulysses that caused a great flood carrying mud and debris through my hometown in the Philippines. In the absence of government preparation, the flood sent people clambering to find higher ground or fleeing to their roofs. Upon landfall, the typhoon instantly killed thirty-nine people. The military, which was fighting insurgent communists in the Sierra Madre mountain range of Luzon island, had to cease their pursuit of rebels to deploy their amphibious assault vehicles for the rescue work in places where waters remained high.

Ulysses hit the Philippines at the height of the coronavirus spread and on the heels of another typhoon which was one of the strongest in the world that year. It destroyed more than 270,000 houses. Tens of thousands of people remain displaced. The Philippines, which lies to the south of Japan in the Pacific rim of fire, has active seismic faults and volcanoes, making it one of the world’s most disaster-prone countries. Stories about losing one’s belongings to a flood are common in my country and this is part of why Hokusai’s work speaks to me.

In despair over devastating floods in Manila and months of isolation in my room on the twentieth floor of a building in the Lower East Side in New York, I relate even more to Hokusai, Bernardo, and Albers. During our video calls, my daughter would frequently poke the phone as if wanting to reach out to the person behind the screen. Mostly thinking about events on the other side of the world, my sense of belonging and location became unmoored from any one time or place. A part of me is drowning in the mud of a tropical flash flood in Manila, and the other is longing to find home in a city that remains a stranger despite me being captive to it. It’s easy to get hooked on the details of Hokusai’s Great Wave and not notice the tiny Mount Fuji in the far background, which is the real subject of his print. The strange compositional effects that such shifts of scale permit make it seem like the waves will devour not just the men in the kayaks but also a far-away, immovable mountain.

Bibliography

“103 “lost” drawings by Japanese artist Hokusai acquired by the British Museum,” British Museum Press Release, November 21, 2020. https://www.britishmuseum.org/

Albers, Josef. Interaction of Color. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2006.

Anoka Faruqee, dir. Search Versus Re-Search: Recollections of Josef Albers at Yale. New Haven: Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, 2016.

Benesa, Leonidas V. "Constancio Bernardo's Farewell to Albers." In Constancio Bernardo Retrospective Catalog, Manila: Museum of Philippine Art, 1978.

Bernardo, Angelo. Constancio Bernardo: A Life in Sketches. Manila: Soumak Publications, 2016.

Bibliographical compilation for the Constancio Bernardo Foundation, Inc., and the Ayala Foundation, Inc./ Filipinas Heritage Library.

Interview with Constancio Bernardo, August 1, 2002.

Bernardo, Constancio. "A Speculative Analysis of the Study, Creation, Enjoyment, and Evaluation of Art," BFA thesis, Yale University, 1951.

"The Possibility of the Absolute in Painting," MFA thesis, Yale University, 1952.

“Artist’s notes” in Ensemble 1 in November, 17 November – 5 December 1971. Manila: Cultural Center of the Philippines, 1971.

Bunoan, Ringo and Evangelista, Carina. Constancio Bernardo. Manila: Ayala Museum and Soumak Publications, 2016.

Cohen, John, dir. Josef Albers teaching at Yale. 1955; New Haven, CT: Josef Anni Albers Foundation, 2013. https://vimeo.com/77608435

Darwent, Charles. “Josef and Anni Albers: the Bauhaus misfits who scaled art's peaks,” The Guardian, October 10, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/oct/10/bauhaus-josef-anni-albers-art

Davenport, Russel. "A Life Round Table on Modern Art," Life, October 11, 1948.

Dewey, John. Art as Experience. New York: Penguin Putnam, 1980 (15th ed.), originally published 1934.

Horowitz, Frederick A. and Brenda Danilowitz. Josef Albers: To Open Eyes, The Bauhaus, Black Mountain College, and Yale. New York: Phaidon Press, 2009.

Lahusen, Susanne. "Oskar Schlemmer: Mechanical Ballets?" Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research 4, no. 2 (1986): 65-77. Accessed April 30, 2021. doi:10.2307/1290727.

Linton, Donna Mae. "The Sacred Modernist: Josef Albers as a Catholic Artist." Art and Christianity, no. 71, 2012.

Saletnik, Jefferey. “Josef Albers, Eva Hesse, and the imperative of Teaching.” Tate Papers no.7, Spring 2007. Accessed March 1,2021. https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/07/josef-albers-eva-hesse-and-the-imperative-of-teaching

Weber, Nicholas. “Introduction.” In Donna Mae Linton, “The Sacred Modernist: Josef Albers as a Catholic Artist." Art and Christianity, no. 71, 2012.

Subscribe to Broadcast