The Perception Census

On a Thursday morning in early 2015, a photograph of a dress tore across the internet with viral velocity. While half the world saw a blue and black dress, the other half was convinced the dress was white and gold. I happened to be teaching a class on visual perception that day and when I returned to my office I was met by a deluge of voicemails from journalists, all of them trying to figure out what was going on. At first I thought it might be a hoax—the dress being so obviously blue and black to me—but when a couple of researchers in my lab said “white and gold,” we knew something was up. Years later, this realization has snowballed into our current project: the largest ever attempt to measure the different ways we each experience the world: The Perception Census.

The story of The Dress turns out to be rooted in the complicated ways in which our brains take lighting conditions into account when figuring out something’s color. This happens all the time: when you take a white piece of paper outdoors, it still looks white, even though the composition of the light waves hitting your eyes will have changed significantly. Our brain’s capacity for balancing out ambient lighting this way is extremely useful—just imagine how confusing it would be if things changed color all the time.

What The Dress revealed, in a beautiful example of found psychology, was that this process—which psychologists call “color constancy”—can play out differently for different people. For some of us, our brains assume that the photo was taken in yellowish, indoor-style lighting, and so our brains infer the color of the dress to be blue and black. Other peoples’ brains assume outdoor, blue-ish ambient light, which leads to a perception of the dress as white and gold. Because all these color-balancing neural shenanigans go on under the hood, beneath the surface of awareness, people were convinced that their way of seeing was the right way, the only way.

It might be tempting to treat The Dress as a quirk of perception, a one-of-a-kind deviation from the normal business of experiencing the world as it truly is. But this would be a mistake. We never perceive things exactly as they are, and it’s likely that we each experience the world—and the self—in our own, individually distinctive way. Just as we all differ on the outside—in terms of height, skin color, and so on—we each differ on the inside too. But unlike externally visible differences, the diversity in our perceptual experiences—our collective perceptual diversity—has, until now, remained mostly hidden.

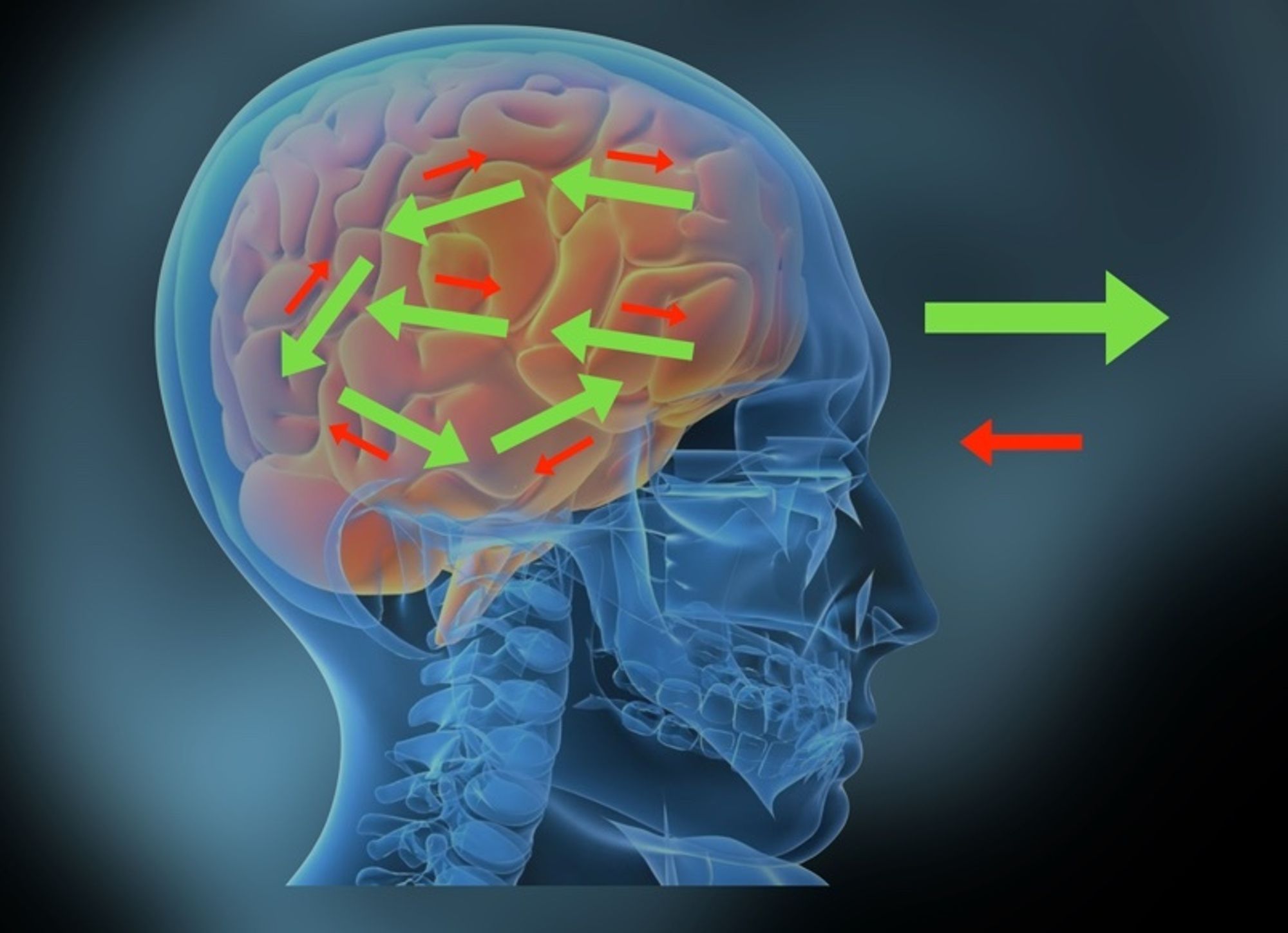

To get a handle on all this, imagine for a moment that you are your brain, trying to figure out what’s out there in the world (and in here, in the body). There you are, snug inside the bony vault of the skull. It’s completely dark and utterly silent. All you’ve got to go on is a constant barrage of electrical sensory signals which are only ever indirectly related to what’s out there. These signals don’t come with labels (I’m from a cat! I’m from a bowl of soup!), and their inherent ambiguity means that perception—the process of figuring out what’s there—cannot simply be a read out of the information they contain.

Instead, experiencing a world, and a self, are inherently creative acts, the results of an active process that comes mainly from the top down (from the brain outwards) rather than the bottom-up (from the world inwards). In my research as a neuroscientist—and as I explore in my book Being You—I’ve come to view the brain as a kind of prediction machine, always in the business of making predictions about what’s out there in the world (or in here, in the body), and using sensory signals to calibrate these predictions. What we experience, in this view, is not a read out of the sensory signals, it is the content of the predictions—the brain’s best guess of what’s going on. We live in a controlled hallucination, a creative construction that remains tied to reality by a dance of top-down brain-based prediction and bottom-up sensory prediction error—but which is never, and can never be, identical with that reality.

One striking consequence of this view is that, since we all have different brains, we will all have different perceptual experiences—even if we are faced with the same objective external reality. And it’s not just The Dress: all of our experiences may differ, whether of a blue sky, the passing of time, or the taste of a peach. What made The Dress special was that the differences in perception were stark enough that they became sufficiently noticeable for the internet to take notice.

To shed light on the hidden terrain of perceptual diversity, I’ve been working with a team of psychologists, philosophers (Professor Fiona Macpherson from the University of Glasgow), artists, and designers to create The Perception Census—a large scale, online citizen science survey of the differences in our inner worlds. It consists of engaging, fun, and easy to complete experiments, brain teasers, and interactive illusions. Anyone over 18 can take part, and as well as contributing valuable data, every person participating can learn about their own powers of perception and how they relate to others. The Perception Census goes far beyond vision, taking in how we experience sound and music, emotions, and the passing of time, as well as exploring peoples’ beliefs about perception and consciousness.

The Census launched in July 2022, and already more than 20,000 people have taken part. Aged between 18 and 80, they’ve come from more than 100 countries, representing every continent except Antarctica, and collectively have completed more than 50,000 research activities. Our full analysis of their responses has to wait until we’re done collecting the data, but a few patterns are starting to emerge already.

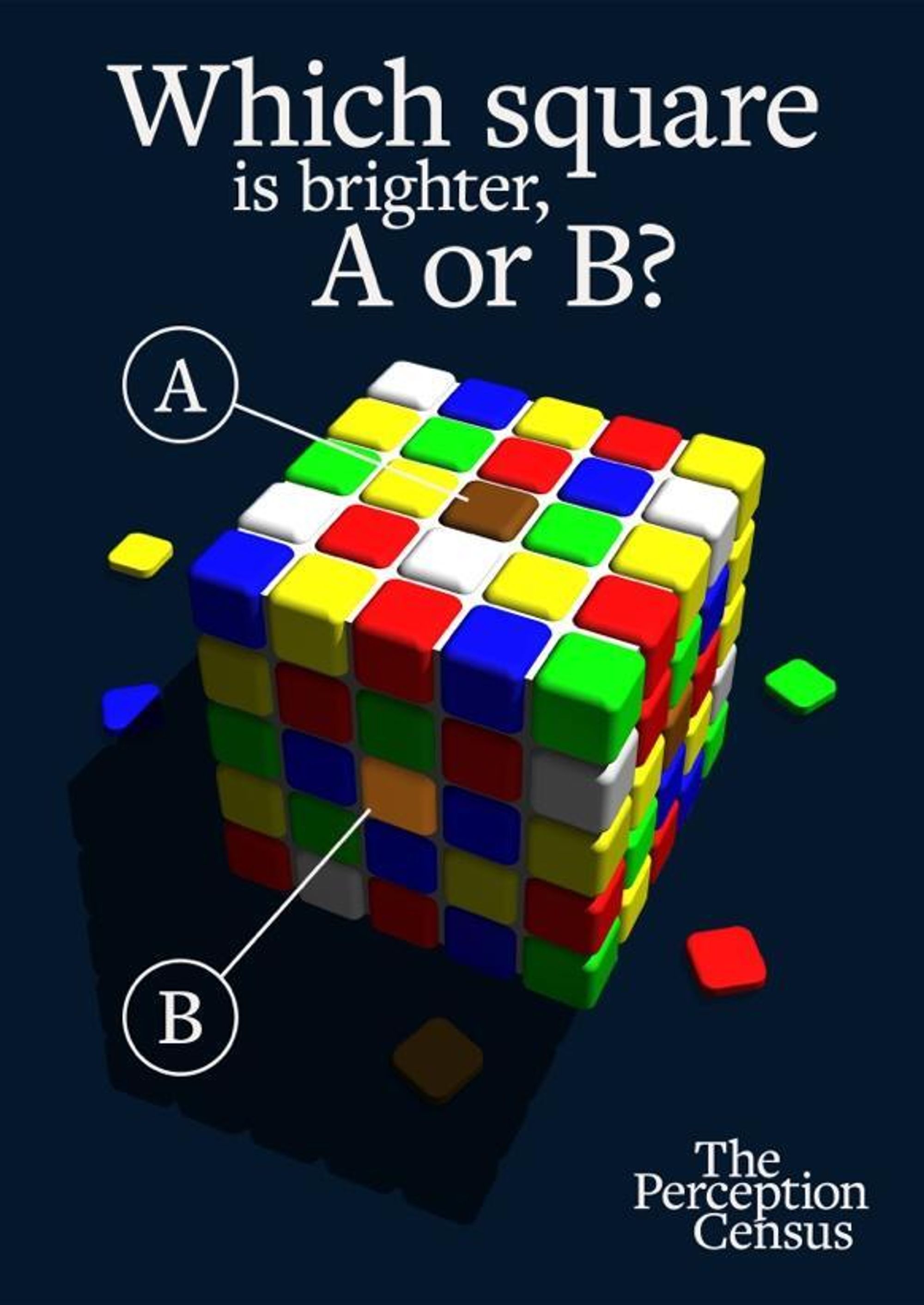

One is directly related to The Dress. We studied how people responded to the ”Purves/Lotto Cube"—a color illusion in which two identical brown squares on a Rubik’s cube appear to be different shades of brown. Similar to The Dress, this effect happens because of the way the brain takes shadows into account when inferring the color of a surface. While the basic illusion was discovered long ago, we’ve uncovered a striking variability in its strength: while 20% of people experience it very strongly, another 20% barely experience it at all. Just as with The Dress, there’s considerable diversity here in how our brains make sense of light and shade.

Other findings from the Census so far include the discovery that 31% of people surveyed reported having an “out of body experience” of some kind, in which their experience of where their self is located is distorted in some unusual way. This figure is surprisingly high, and our hope is that when we look at the rest of the data, we’ll understand why.

There’s plenty more to discover, and the great promise of the Census lies not in any single finding, but in its potential to reveal the ways in which different aspects of perceptual diversity relate to each other. This way, we’ll be able to get underneath the surface of perception to decipher the hidden structure of our inner worlds, and how this structure varies among us.

Besides this exciting scientific potential, I believe that The Perception Census has broader implications for society. One is to deepen our appreciation of neurodiversity, a concept that’s been around for many years. Like perceptual diversity, it emphasizes that every mind is different and that differences are not deficits. However, neurodiversity has over time tended to become associated with specific conditions, such as autism, ADHD, or synaesthesia (a mixing of the senses, which we also survey in the Census). Ironically, this may have had the effect of reinforcing the false idea that there is a single correct neurotypical way of perceiving the world, with neurodivergent conditions representing deviations from neurotypicality, each with benefits and drawbacks.

The concept of perceptual diversity, when illuminated by findings from The Perception Census, may help restore the original intuition behind neurodiversity. There is no single correct way of perceiving: all of perception is constructed, and we all differ. Sometimes these differences are large enough to surface into language and behavior, but most of the time they probably aren’t. When we recognize that our perceptual experience is not revealing things as they are, but as we are (as the novelist Anaïs Nin put it), we’ll be better able to realize that inner diversity applies to all of us, and that it enriches our society just as our externally visible diversity does. Here I’m drawn to the parallel with biodiversity, where it's abundantly clear that diversity is essential to a healthy ecosystem. A diversity of minds likewise may be essential for a flourishing society.

I also believe that a greater appreciation of perceptual diversity could help cultivate a new humility towards our own experiences. The Dress exposed the doggedness with which people cling to their way of seeing, a doggedness which to my mind is grounded in the very nature of perceptual experience, which makes it seem like the world we experience is independent of our brains and minds even when we know that it isn’t. Recognizing that the way we see things might not be the way they are, and different too from the way others might see the same things, could provide new platforms for empathy, understanding, and communication—even between people with very different views. In our increasingly fractured and polarized world, this is needed now more than ever. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast