A Lily Pad on the Muck

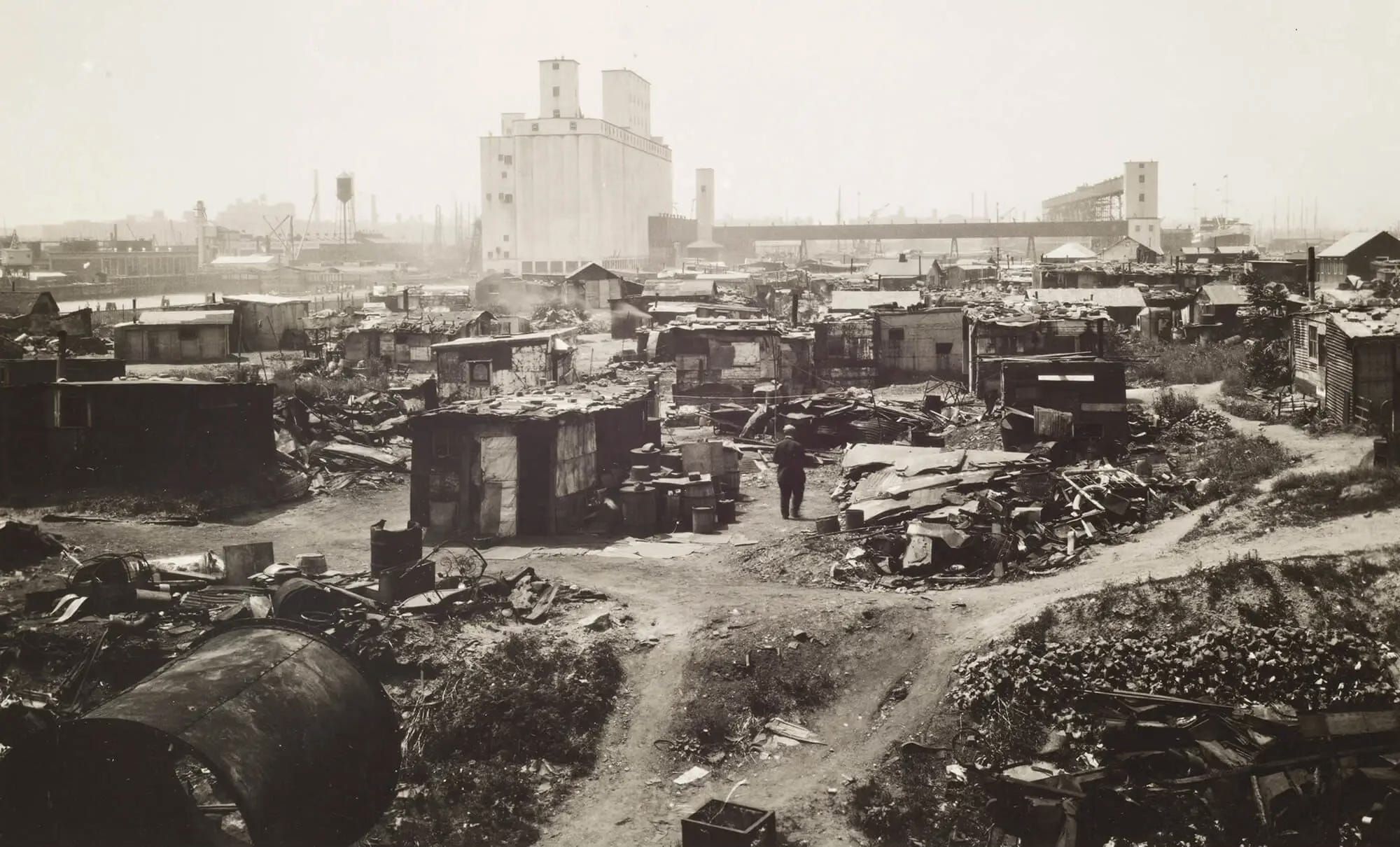

Pioneer Works, pre-renovation, from the parking lot that's now a garden, 2010.

Photo: Daniel KentThis essay appears in print in our latest issue—alongside pieces by Emily Raboteau, Marcus J. Moore, and Catherine Lacey; poems by Eileen Myles, Ariana Reines, and Brandon Kilbourne; and drawings by Daniel Johnston.

The excavators, no matter how far down they went, couldn’t find a foundation. Down and down they dug, but all they hit was soft—gravel; sludge; dense mud that stank, beneath a certain depth, of oil. This was surprising, given where they were digging: under the heavy brick walls of an old industrial building, three stories high, whose structure isn’t light. An edifice this heavy needs to rest on something. This one, which dates from 1866, sits a few blocks from the water in Red Hook, Brooklyn. Once, it housed an iron works. Now it houses Pioneer Works, an organization devoted to the arts and science that was readying to install an elevator to its upper floors. The elevator required a footing, which is why the excavators were pawing under its walls—and finding nothing. This, to the place’s current stewards, was concerning. But the engineers, happily, said not to worry.

“That’s just how they built back then,” explained Willie Vantapool, who oversees the physical plant here. “Compact the dirt, slap some tar on timber, and up you go with your first course of brick.” Willie is a gentle man with a punk rock mien whose old Dutch surname isn’t the only trait that makes him a paragon of old New York. “That’s how they did it. And it hasn’t settled an inch.” He means this literally: when the engineers pointed a laser at the base of the wall 150 feet from where we’re standing, at the other end of the cavernous Main Hall, they found those walls to be within a thumb’s width of level, all the way across—despite being built on fill and atop what once were waves. This feels impossible. But also, somehow, apt. This brick-and-mortar monument to industry, which was built for smelting iron but is now filled with ideas and crowds thronging to talks on dark matter in outer space, isn’t so much sitting as it is floating on Pioneer Street. A lily pad on the muck.

Pioneer Works Main Hall, 2018.

Photo: Walter Wlodarczyk“This was spartan construction,” Willie says. It feels hard to believe, gazing at the high west-facing brick wall of windows and gigantic beams—hewn from old growth pine, Willie says. Some of them are 40 feet in length and 16 inches across, and span a Main Hall proclaimed gorgeous by most who see it. But in the nineteenth century, this was the equivalent of knocking up a metal-walled warehouse today to churn out your newest byte-powered invention. It’s fair to assume that most contemporary visitors to the space, whether they’ve come for an outré art show or a concert from august alumni of Sonic Youth, don’t much ponder what its gantries lifted: the place’s look hews to a term—"industrial”—which in twenty-first century Brooklyn is more often used to describe an aesthetic than invite consideration of the actual industries such spaces were constructed to house, and the people who built them and kept them whirring.

Among the once-industrial neighborhoods of Brooklyn’s waterfront, it wasn’t long ago that Red Hook was best-known as a place to avoid. Few New Yorkers came here beyond the 6,000 of them who lived in the Red Hook Houses, the largest public housing project in the borough. In the 1990s, packs of wild dogs roamed the wharves. Now the very qualities that lend the neighborhood its marginal air—quiet streets and proximity to the water; old warehouses and maritime mystique; a certain essence of down-home grit despite the changes—are what draw brunch-seekers on weekends to eat lobster rolls and ogle pricy art. Transit access may still be an issue. But now the main hazard to getting here, if you fancy riding an e-powered Citi Bike down from Brooklyn Heights, is making sure all the docking stations aren’t full. More civilized still is hopping an express ferry from Wall Street to the once-teeming but now serene Atlantic Basin, a brick’s throw from Pioneer Works.

The Pioneer Works Main Hall, pre-renovation, featuring Cosmo the dog, 2010.

Photo: Brett WoodPioneer Works Science Studios, pre-renovation, 2010.

Photo: Brett WoodBut the ghosts of this area’s industrial past still linger, if you know where to dig in this old “hook” that was named in colonial days for the red hue of its dirt. Not long ago, I aimed one of those Citi Bikes against the flow of brunch-seekers and toward Pierrepont Street, where the Center for Brooklyn History keeps its archives. I wanted to learn about the acquisitive and eccentric men who built Pioneer Iron Works to serve an industry—the sugar trade—that shaped New York and the Caribbean islands to which it’s long been joined.

*

“Only the dead know Brooklyn,” wrote Thomas Wolfe of the churn of creative destruction that makes capturing the ever-changing character of this borough’s neighborhoods feel like a task achievable only by communing with souls no longer here. This is as true today as when Wolfe published his classic short story in The New Yorker in 1935. Maybe it’s true of all cities. Or of all urban zones, at least, that are typified by now-familiar cycles of industrial development begetting post-industrial decline begetting the arrival of artists whose presence inevitably leads, once financiers start dating the artists, to gentrification on speed. But it’s perhaps particularly true of the long-marginal neighborhood by the borough’s edge where Wolfe set that story for a reason. Red Hook’s historic denizens have included not a few mobsters, illicit importer-exporters, and others good at keeping secrets.

It was in the 1840s that the Atlantic Basin’s carving from the Buttermilk Channel’s shallows transformed this marshy district of islands and streams into a bustling port. Boosters of that protected 35-acre anchorage, soon to be dotted with ships from around the globe, dubbed it “the eighth wonder of the world.” Boosters of the Brooklyn Bridge made a better case when they applied the same tag to their stately span a few decades later. But the Atlantic Basin’s dredging was accompanied, with the help of rubble from the flattening of nearby Cobble Hill, by the infilling of adjacent waters atop which new streets were soon lined with tenements and stores. A decade later and just down the shore, the even-larger Erie Basin was built by local potentates to connect Brooklyn’s waterfront to the bounteous resources now floatable here, via the Erie Canal, from America’s heartland. Its other edges and nearby quays were lined with stately brick “stores” that one of those merchants built during the Civil War to fill with wheat and bricks and lumber and ore.

Hooverville in Red Hook, c. 1930–1932. Photographic print showing the land now occupied by Red Hook Ball Fields, public pool, and NYCHA housing, with the grain terminal visible in the background.

Today one such waterfront storage, built by William Beard, houses high-end homes and ateliers within handsome arced windows and thick walls. But in the late nineteenth century, the wharves those stores served sparked the industrial development of the area as the once-sleepy town of Brooklyn sprawled across Long Island’s nub. By the time urbanized Brooklyn became a part of greater New York City in 1898, thousands of factories were turning out pencils and varnish and tin cups and brassieres, along with heavy machinery to build the roads and bridges and boats of an industrial age. Greater Gotham became the world’s foremost industrial metropolis. And in Red Hook, it wasn’t only minders of dry docks and grain elevators who set up shop within spitting distance of the piers.

The most famous sugar refinery on Brooklyn’s waterfront was up in Williamsburg: The Havemeyer family’s American Sugar Refining Company, which in 2014 became home to a famous public art piece by Kara Walker dilating on its past, churned out the Domino brand of crystals that still dominates the U.S. market. But Red Hook, in the sugar department, was no slouch. Once, the American Molasses Company’s huge vats of syrup sat where an IKEA now sprawls. Next door, the Revere Sugar Refinery’s distinctive pyramid-shaped buildings loomed over the Erie Basin’s eastern edge for decades. The nearby Lidgerwood Manufacturing Company sent goods in the other direction. Its workers turned out grinders and boilers for sugar mills in the Caribbean, as well as patented tools for husking coffee beans, for customers in Brazil and across the Americas’ tropics. Later that century, Lidgerwood’s workers also forged winches and cables that were vital to digging the Panama Canal.

Red Hook’s piers helped make New York rich; they also linked Brooklyn to the world. Among the shipping companies whose vessels called Red Hook’s piers home were outfits plying regular routes to Haiti and San Domingo (the Clyde Company); Mexico (Ward’s); and Puerto Rico (the New York and Porto Rico Steamship Company). The latter’s vessels brought to New York many of its first Puerto Rican immigrants in the early 1900s. And the docks, peopled with sailors who crewed ships and stevedores who loaded and unloaded them—and the gangsters and bosses they worked for—also shaped the rough-and-tumble history of nearby blocks.

Access to work on those docks was commonly controlled, in the early 1900s, by Irish gangsters who apprised the daily “lineup” of hopeful stevedores—until the mafia moved in and an Italian organization called the Black Hand took over Red Hook’s wharves. In that same era, when the Black Hand gave famous gangsters like Al Capone their start, a strong community of Norwegian seamen established itself near the docks—and saw many of its transient members stranded there when shipboard work dried up during the Depression. Many of them took up residence in the “Hooverville” of shacks that sprawled across low-lying land east of Pioneer Iron Works. Robert Moses bulldozed the shantytown in 1936 to build a vast public pool, and then the Red Hook Houses was built there a few years later. Moses, the notorious “power broker” who shaped the city’s built environment for decades, also presided over the opening of the Gowanus Expressway that cut the Red Hook Houses off from the rest of Brooklyn and was later widened into the airborne six-lane monstrosity known as the BQE.

Aerial view of the Red Hook neighborhood, Brooklyn, c. 1950. The working waterfront and Erie Basin Terminal appear in the foreground, NYCHA public housing projects to the right, with Lower Manhattan and Governors Island in the distance.

By the time that happened, New York’s center of gravity for maritime freight was already leaving Red Hook when Marlon Brando turned its docks into the backdrop for an immortal role in On the Waterfront (1954). With the advent of container shipping in the 1960s, that center moved definitively to New Jersey (notwithstanding the small container port that remains). A few of Red Hook’s factories held on. At the Revere Sugar Refinery, workers kept clocking in until its parent company went bankrupt in 1985, and left its rusting buildings to molder by the sea (where you can glimpse them, in the 1994 cult film The Search for One-Eye Jimmy, behind a crusty fisherman played by Samuel L. Jackson). The hulking old home of the Lidgerwood Company was bought a few years ago by UPS. Now its old block will be home to a “last-mile” warehouse for parcels bound for Brooklyn’s bourgeoisie.

Such is the fate of many properties on this old industrial waterfront that’s now given over to nodes of a new economy exemplified by IKEA and the Amazon warehouse next door, from whence a steady stream of frowning delivery people now rolls on e-powered cargo bikes stamped with their employer’s smiley logo. But a couple of blocks from the Atlantic Basin’s edge, the husk of another old Iron Works with ties to the sugar trade survives from when it was built on a street once called Williams but renamed Pioneer Street in honor of its foremost factory.

*

The adventuresome young industrialist who built Pioneer Iron Works in 1866 was 39 years old. Alexander Bass hailed from Pennsylvania’s coal country. He trained there as a machinist on the railroad before he decamped for Cuba in his 20s to seek his fortune. Cuba in those days was still a Spanish colony. But its ports had opened to trade with the United States just after the Haitian Revolution saw a million enslaved Africans rise up on the nearby island of Hispaniola, to kill the owners of the French plantation colony that was the world’s leading source for sugar until the late 1700s. In the Caribbean, some six million enslaved Africans were trafficked during the Triangle Trade to feed the world’s hunger for sweetness. The end of slavery on British islands like Jamaica and Barbados in the 1830s also dented those islands’ capacity for sucrose-making. In Cuba, by contrast, slavery didn’t end until 1886, and there the sugar trade boomed throughout the nineteenth century.

Bass began his career by offering his services as an engineer to Cuban owners of slaves and sugar mills in whose businesses he soon also became an investor. He wasn’t the only American to alight in those years on this huge island 90 miles from Florida that Thomas Jefferson proclaimed “the most interesting addition that could ever be made to our system of states.” Conveying Cuban sugar to sweet-toothed U.S. consumers was a big American business. But Bass was the only one of Cuba’s American sugar barons to secure a patent for “temporary railroads” that moved cut cane from field to mill. This innovation inspired Bass, who doesn’t seem to have lacked for self-esteem, to regard himself a vital pioneer: He resolved to open a new iron works in Brooklyn to exploit his patent.

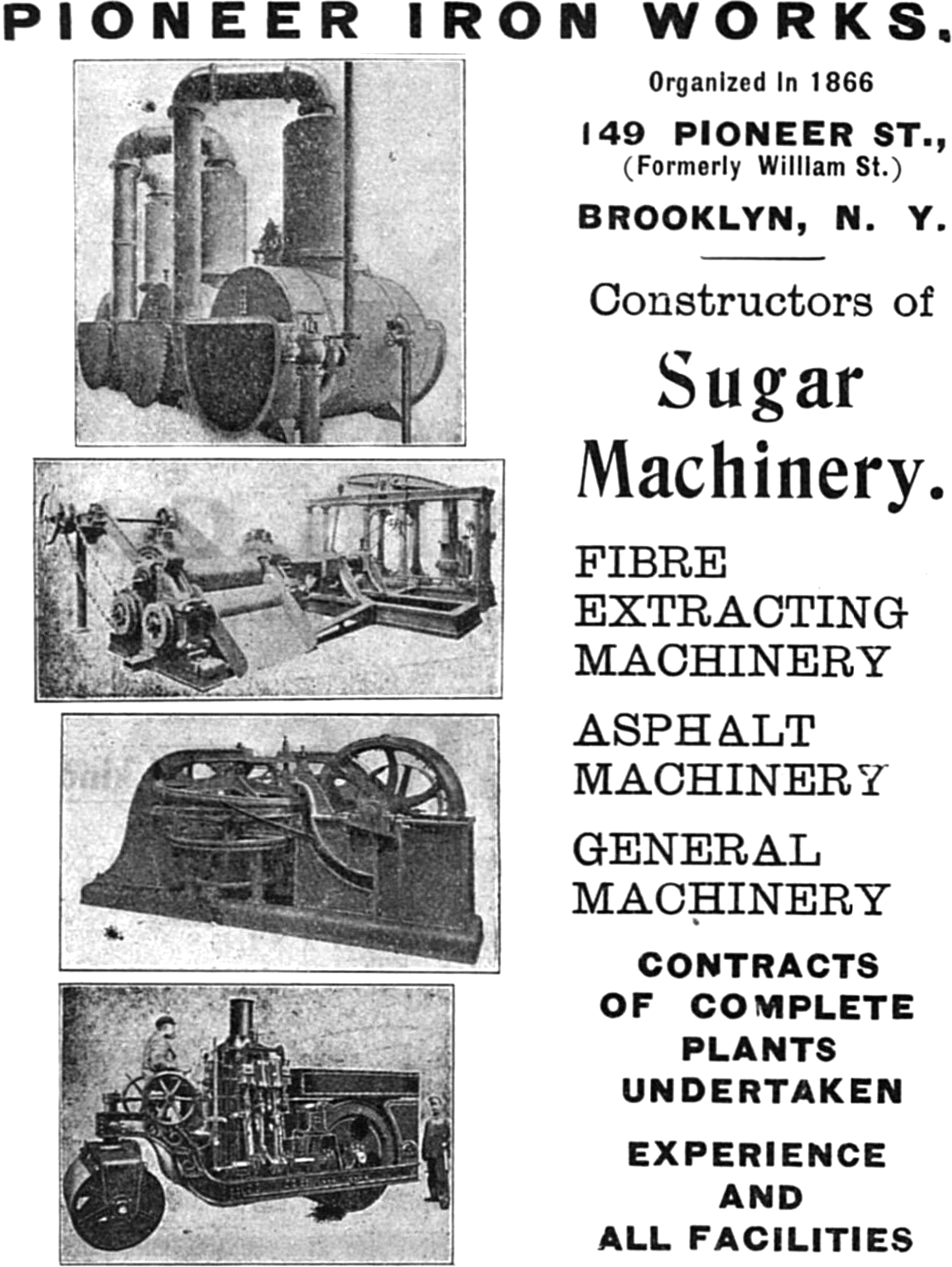

Advertisement for Pioneer Iron Works, 1904. Note change in address from "Williams Street" to "Pioneer Street."

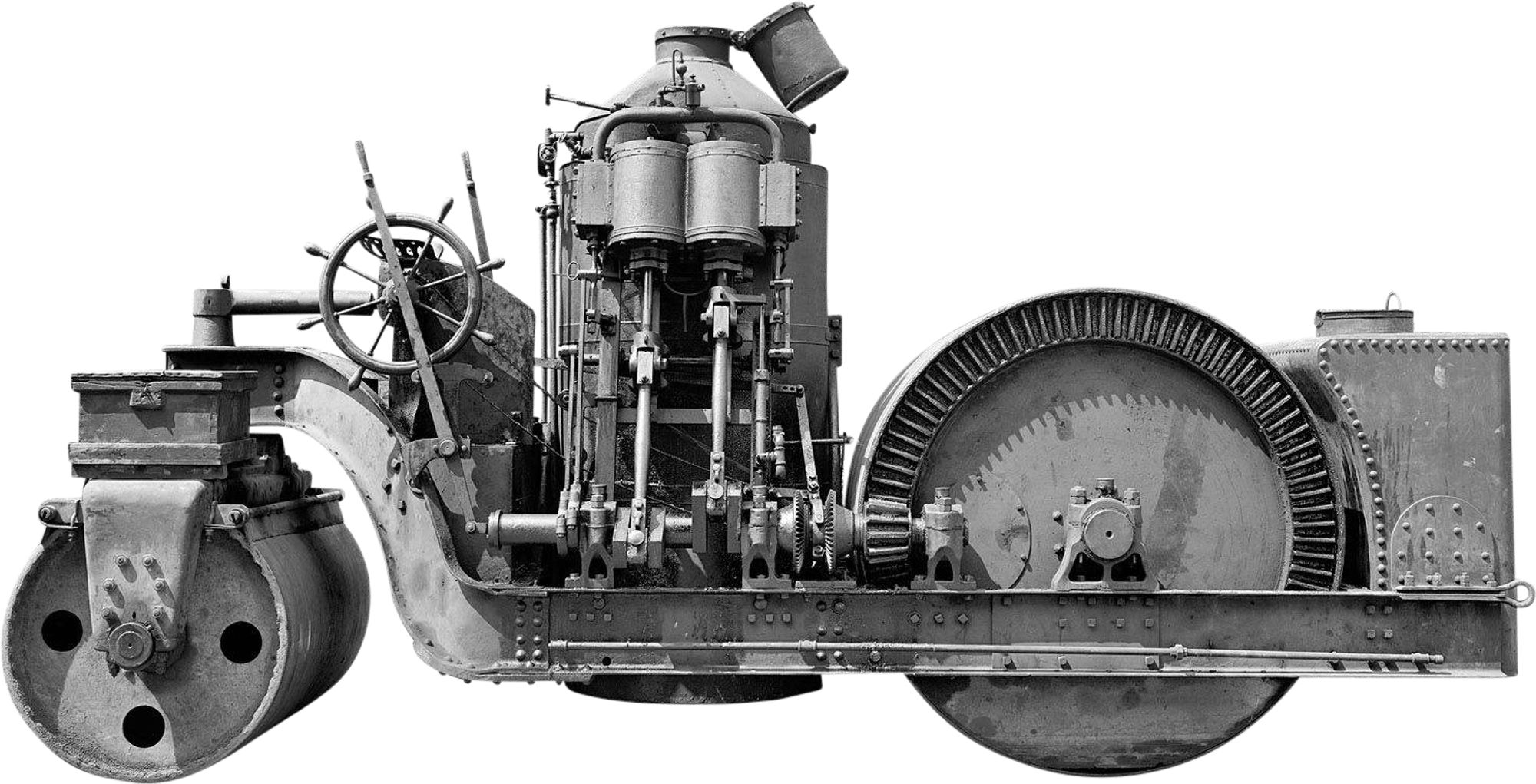

In 1865, in Havana, Bass had a son named William. The next year, Bass the elder sailed to Red Hook to open Pioneer Iron Works on newly reclaimed land by the Atlantic Basin. He took out ads in Scientific American featuring a drawing of Bass’s patented Portable Iron Railroad and touting the factory’s focus: “Machinery for Sugar Houses and Plantations a Specialty.” Equipment from Pioneer Iron Works, made for builders of sugar mills from Louisiana to Cuba to Puerto Rico, became a mark of distinction. The company also diversified by forging tar kettles and acquiring a patent in 1873 to produce the Lindelof Steam Road Roller: a striking beast of the industrial age that surfaced streets across America.

Lindelof Steam Road Roller, manufactured at Pioneer Iron Works, c. 1920.

Alexander Bass evidently profited nicely from these products; he made his home in a stately townhouse facing Prospect Park, from which he commuted to his Red Hook factory when he wasn’t looking after his interests in Cuba. By 1881, Pioneer Iron Works was employing over 60 workers—a fact we know because all 60 lost their jobs, at least temporarily, when on October 27 of that year a fire devastated the building. Likely caused by a malfunctioning furnace, the flames took nearly an hour to extinguish and left some $60,000 in damage. The Iron Works, thanks to insurance, was quickly rebuilt.

Among the archives of Brooklyn’s newspapers mentioning the company in those years was a story from 1882 reporting that the beneficent officers of Pioneer Iron Works were moving, on Saturdays, to close the Works at 3 pm, “to enable their employees to obtain recreation in the afternoon and to give their wives ample time for shopping.” Another reported on the sporting endeavors of those employees, “among whom the cricket fever has broken out quite fiercely,” said The Brooklyn Daily Times: The Pioneer Cricket Club, taking advantage of those free Saturday afternoons, played a weekly game in Prospect Park.

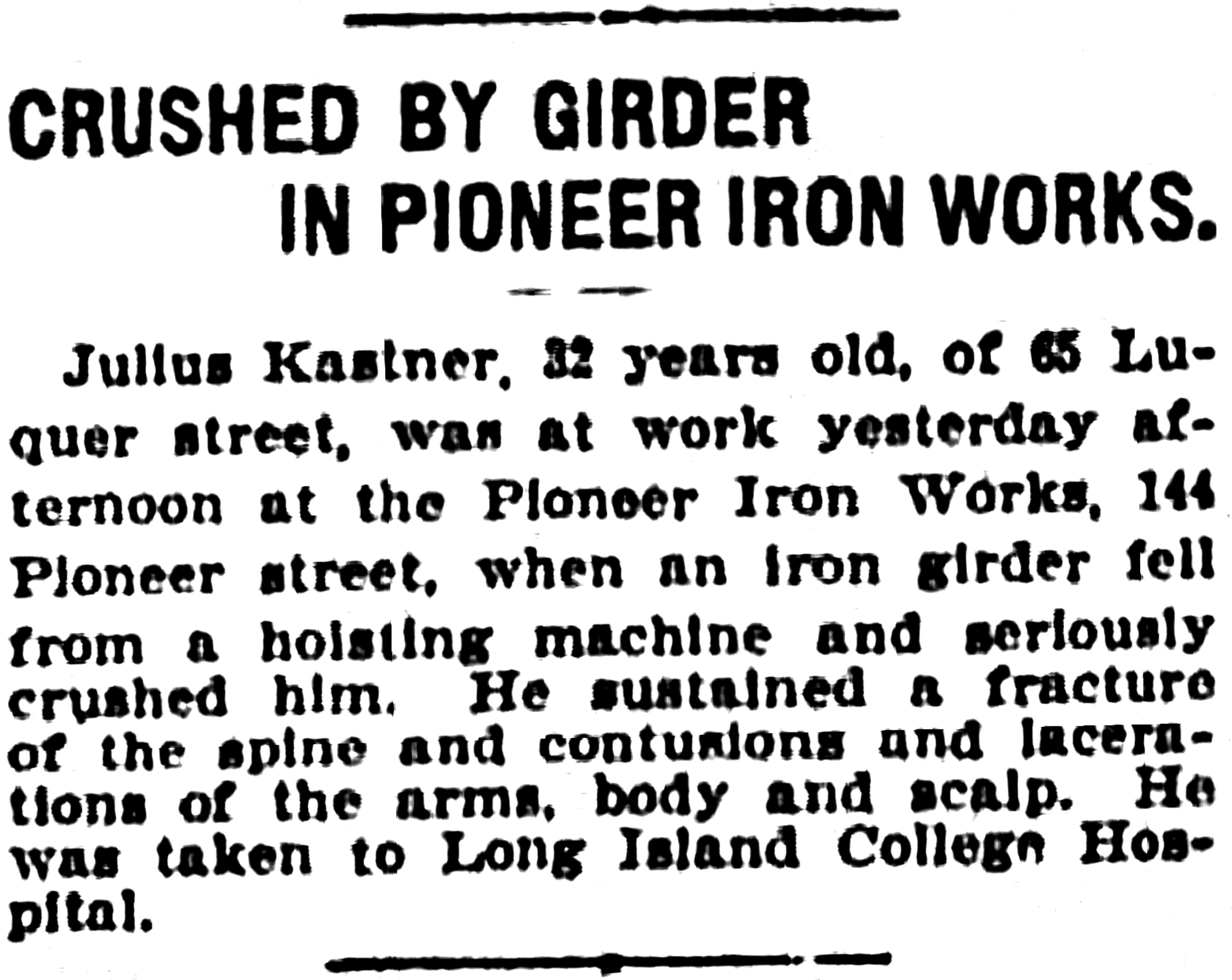

Alexander Bass, from his park-side home, didn’t always enjoy pacific relations with his workers. In May 1886, mechanics, boilermakers, and patternmakers at Pioneer Iron Works went on strike to demand that their workday be shortened from 11 hours to nine, and that they be paid for 10. Bass’s response was to can them. But 13 years later, the writer of a letter to the Brooklyn Daily Citizen praised Bass for finally instituting the nine-hour day and for the fact that the factory’s workers, who now numbered 130, “were handed a glorious turkey wherewith to celebrate their Thanksgiving.” Hours and turkeys were one thing; working conditions were another. In 1905, the Times Union reported that a Pioneer employee by the name of Julius Kastner, 32, was “seriously crushed” by a girder that left him hospitalized with a fractured spine. The next year, another devastating fire destroyed the Iron Works. Again, it was rebuilt.

"Crushed by Girder in Pioneer Iron Works," Brooklyn Times Union, September 29, 1905.

By that time, the elder Bass’s passing in 1897 had won prominent obituaries in Brooklyn’s papers. His son and sole heir William—who declined to become president of Pioneer Iron Works; an associate of his father’s did so instead—had earned a prominence that outstripped his father’s in the sugar trade to which he was born. Where his father made his first fortune in Cuba, though, William made his in the Dominican Republic. The Basses’ doings there dated from a stormy period in Cuba known as the Ten Years’ War—the first of three wars in which Cuba fought for its independence from Spain, lasting until 1878. Many of the island’s American sugar barons, who would remain big players in Cuban affairs until Fidel Castro’s Revolution kicked them out a century later, rode out the war. Alexander Bass didn’t. He saw an opportunity to develop the sugar trade on the opposite end of Hispaniola from Haiti, in the old Spanish colony there whose cow-hands and merchants, in 1844, had founded the Dominican Republic by claiming their independence not from Spain, but from the new Haitian state whose leaders claimed sovereignty over all of Hispaniola. Bass bought extensive acreage in the young nation, in its eastern province of San Pedro de Macorís as well as a struggling sugar mill in a small town called Consuelo.

Mr. William L. Bass, c. 1906.

The same year he did, in 1886, Bass’s son William turned 21 and set about building a sugar empire centered around their mill in Consuelo, with the help of equipment from Pioneer Iron Works. “Of the group of foreign and local businessmen who dedicated themselves to promoting the development of the Dominican sugar industry,” according to a posthumous profile in Santo Domingo’s Diario Libre, William Louis Bass “stands out in particular [as] a figure endowed with extraordinary dynamism and a multifaceted personality.”

Until the 1880s, the Dominican Republic’s sleepy economy had been dominated by cattle ranching. But with the arrival of William Bass and the rise of other sugar pioneers, the country became a new player in the world sugar trade—and saw its landscape and populace transformed by the railroads that Bass built, per Diario Libre, to “expand the sugarcane frontier.” Among his other innovations, as a modernizer of industry on the D.R.’s fertile plains, was his bright idea to import cocolos—or impoverished Black cane-cutters from nearby islands—to work the fields for their yearly harvest.

*

Soon enough, the Basses’ sugar mill in Consuelo, some 60 miles to Santo Domingo’s east, became the most productive ingenio in the country. With miles of rail lines bringing train carloads of cane to its great grinders and boilers, the mill—which Bass ran until 1915—could turn out 4,600 tons of raw sugar per day. During stints home from the tropics, William made Brooklyn’s papers for giving speeches in which he advocated, after Cuba finally won its independence from Spain with American help, for turning the Dominican Republic into a de facto colony of Washington, like Cuba and Puerto Rico were. This position perhaps had more to do with his business interests than with principle: Bass wanted Dominican-produced sugar, subject to much higher tariffs than sucrose from those other islands where he’d worked, to have equal access to the U.S. market.

Half-title page of Cane Juice Defecation by W.L. Bass, 1905.

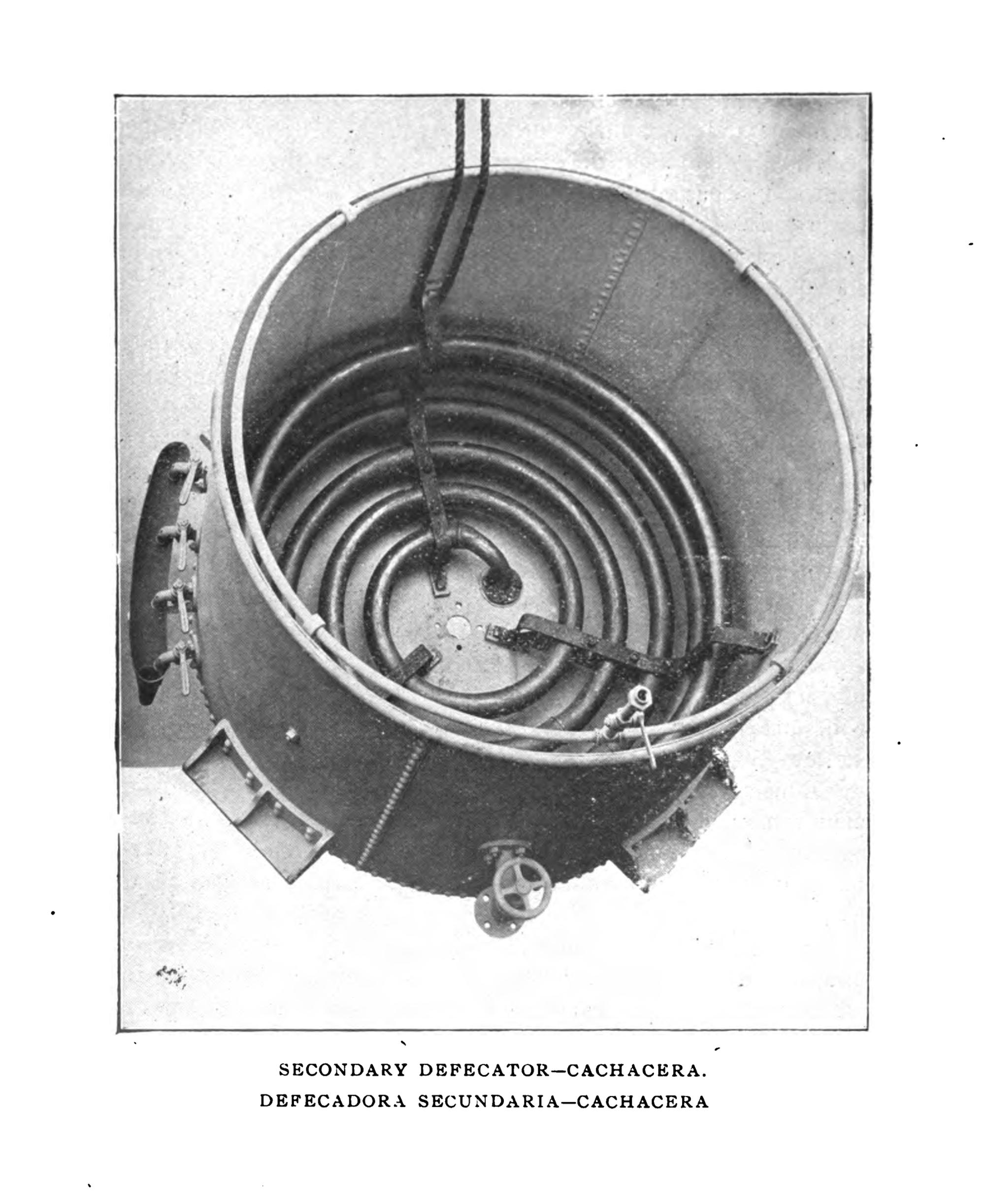

Secondary Defecator (Defecadora Secundaria) manufactured at Pioneer Iron Works, 1905.

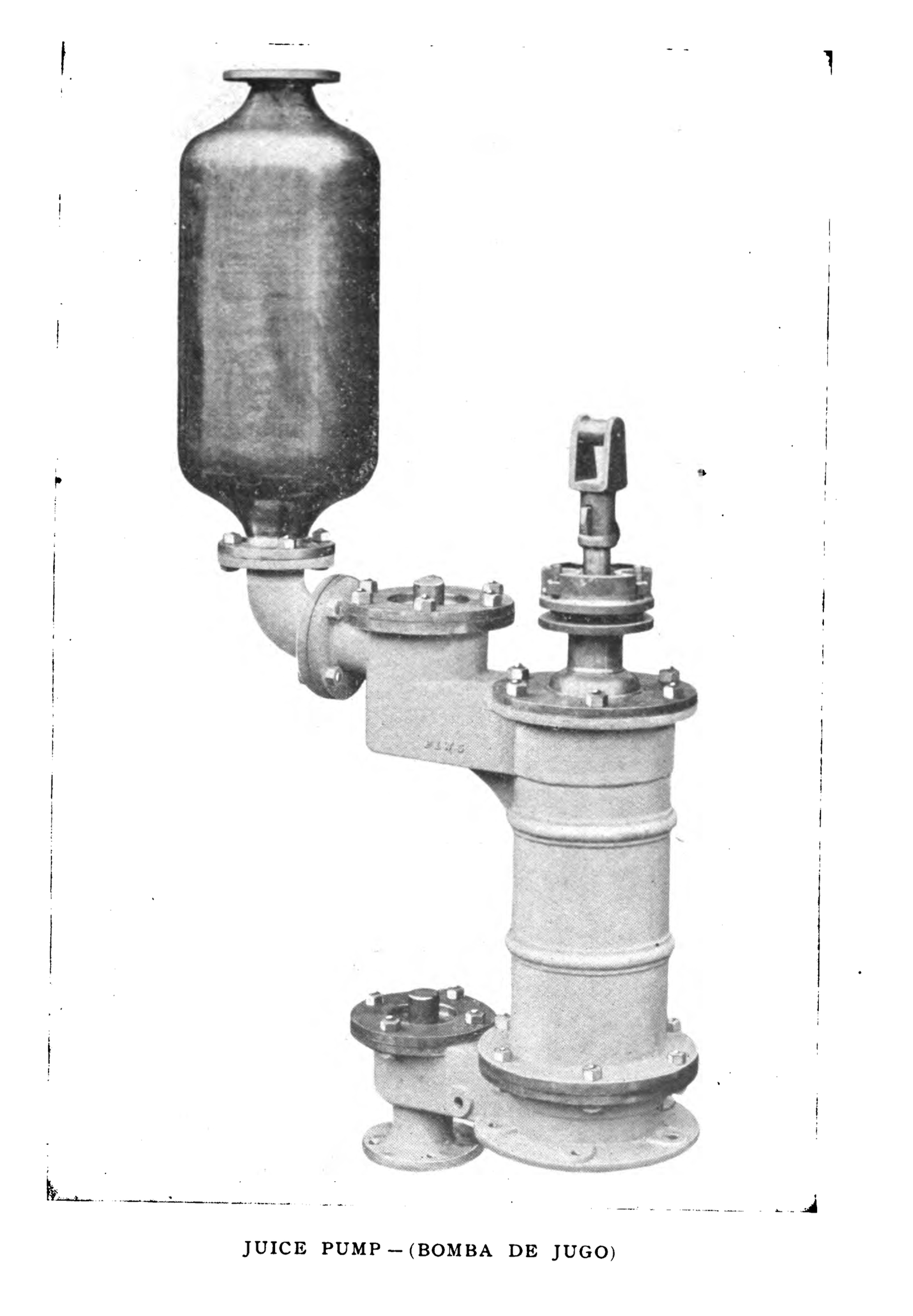

Juice Pump (Bomba de Jugo) manufactured at Pioneer Iron Works, 1905.

To this end, he published pamphlets on trade policy and underscored his stature as a titan of his trade by publishing a 500-page tome, succinctly called Sugar Cane, that detailed every alchemical aspect of how rough cane is turned into powder. A briefer volume, off-puttingly titled Cane Juice Defecation, focused on the roles of guarapo—cane juice—in that process. Bass also fancied himself a poet, and in 1909 published a book of self-aggrandizing doggerel about his Dominican endeavors. It was illustrated with grainy photos of railways, cane fields, and of Bass with Black laborers who worked his estates and whose Jamaican accents he mimicked in verse: “Mista wheelee, you’se ah bad man” / I hear from dependents each day.”

A photograph of William Bass from his book, Thirteen from the Front: A Memento (Washington, D.C.: Press of Wallace & Cadick, 1909).

Bass’s bibliography, evincing a more expansive intellect, didn’t end there. After retiring to New Jersey in the 1920s, he nurtured a fascination with the night sky that one imagines him ogling on warm nights by his fields in Consuelo. He contemplated astrophysics and Einstein’s new theory of relativity, which he became curiously determined to debunk. To that end, in 1928 he published a trilogy of textbooks on what he termed “celestial growth,” called Cosmogony, Astronomy, and The Study of Time. He dedicated them all to the memory of his father, “whose slogan of accomplishment,” William wrote, was “Give me a fulcrum and I’ll move the world!”

That attitude, borrowed from Archimedes, seems to have run strong in the Bass men—notwithstanding the unpaid and underpaid labor from which their accomplishments and lucre also derived. And William’s love for the cosmos, by some cosmic force that seems to draw fellow devotees of spacetime’s deepest questions to this corner of Red Hook today, anticipated how such questions persist at Pioneer Works. A new elevator will also soon bring visitors to its reinforced roof and New York’s first public observatory: a domed portal to the heavens whose centerpiece—a magnificent 1895 telescope, nearly 16 feet in length and with a lens 12.5 inches across—dates from the same era as this building. William Bass was a man of that era, when humankind’s capacities for mechanical engineering were at their peak. More an armchair astronomer than a pioneer of the field, he was best known to its followers for his meandering attempts to disprove Einstein in letters he sent to The New York Times and elsewhere. But his love for such polemics found amused favor with Pioneer Works' Founding Director of Sciences, Janna Levin, when I showed her Bass’s assertion, on the first page of his Astronomy from 1928, that, “Astronomy is the most interesting and simplest of topics.” It was a fact, in his view, made “obvious by the number who elect to take up the subject, particularly among the fair sex.”

Astronomy--1928 by W.L. Bass, 1928.

In 1932, a final mention of William Bass’s name appeared in the Times when the paper reported that his Spanish-style mansion and library in New Jersey’s horse country had been struck by lightning and burned to the ground. In the fire’s wake and in his dotage in 1936, he reengaged the Caribbean by publishing a pamphlet in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, urging the country’s president—his plan never came to fruition—to turn the Haitian island of La Gonâve into a “free zone and free port” for American investors and tourists. He expired some time before Pioneer Iron Works did, at the close of World War II. His father’s old Iron Works, in ensuing years, was occupied by a moving company. Its great hall, once home to gantries and industrial iron, was filled with knickknacks and couches.

*

The knickknacks and couches were still there, 70 years after Pioneer Iron Works closed, when in 2011 the artist Dustin Yellin managed to buy the dusty home of the Time Moving & Storage Company. Yellin and associates, including Gabriel Florenz, the Founding Artistic Director of Pioneer Works (who now serves as the organization's Executive Director), turned the old factory’s carcass into a chapel of culture where history’s scars still linger: One of the giant beams in the third floor Science Studios, as Willie Vantapool showed me, is still charred from those nineteenth-century fires. A few years after this place’s opening as Pioneer Works, I watched a shipping container full of artworks from the other end of Hispaniola—Haiti—land here from the port nearby. Those works’ provenance in the capital of the Caribbean’s first Black republic isn’t all that made POTOPRENS: The Urban Artists of Port-au-Prince such an important exhibition at this old Iron Works. But it’s part of what lent special heft to the dots the exhibition connected, between Brooklyn’s waterfront and the Caribbean, that I pondered as I boarded a plane for Santo Domingo, more recently, to find what remains of the sugar empire whose building was enabled by the iron works once sited at 159 Pioneer Street.

Dustin Yellin exploring the Pioneer Works building, 2010.

Photo: Brett WoodThe week that I left, a new president in the White House was making waves with policy pronouncements pulled straight from the playbook of a predecessor, William McKinley, who Donald Trump loves as much as William Bass did. In the 1890s, McKinley prosecuted policies animated by gunboat diplomacy and racist grievance. Now Trump, hell-bent on rewinding America’s cultural clock to that era, had just made news in the D.R. by removing a U.S. ban on sugar grown there by the country’s largest landowner and sugar producer, the Central Romana Corporation. Their product, sold in the U.S. under the Domino label, has attracted ill attention for its labor practices—which involve paying rights-less Haitian cane-cutters, who live in clusters of shacks in the fields called bateys, pocket change per day for their toil. But those facts, for Trump, are of course less germane than the fact that Central Romana is owned by political cronies of his in Florida.

From Santo Domingo’s airport, I drove east along a highway lined with garish love motels touting rooms for rent by the hour, and baseball academies run by major league clubs—the Dodgers, the Royals—where young Dominican boys dream of cheating poverty with their skills. The capital’s sprawl thinned out into cane fields not long after I passed a road named “Ruta 66 - Honor de Sammy Sosa”—a highway hailing the number of home runs smote by the Dominican slugger during a record-chasing season—and continued toward a city whose nickname, in this baseball-mad land, is La Cuna de los Campocortos: the cradle of shortstops. The provincial capital of San Pedro de Macorís isn’t only known for producing major league infielders, though, as a monument by the city’s edge made plain. I paused to snap a picture of what sits there atop a broad plinth: a vintage locomotive from the era when William Bass stretched miles of narrow-gauge rails, built at Pioneer Iron Works, through nearby fields.

I angled north through the cane for 20 minutes, dodging buzzing motoconchos, to arrive at Consuelo, a heedless sprawl of cinderblock homes and bumpy lanes dotted with colmados selling jumbo bottles of Presidenté beer and small bags of plantain chips. By the town square, an old man told me about how when he was a boy, the mill here had become the property of the dictator Trujillo. He said the mill’s last Zafra, or harvest, was in 1999, and gestured toward the brooding ruins amidst tropical trees a few hundred feet away. The main mill building had been torn down, but a gun-toting guard was glad to let me into an acre-sized hall filled with giant iron thimbles and gantries and mysterious machines—and to point me toward where another steam engine from the era of this ingenio’s founders sat covered in vines, moldering in the heat.

Retired cane-cutters near Consuelo, San Pedro de Macorís, Dominican Republic, 2025.

Photo: Joshua Jelly-SchapiroRemnants of the old railroad, manufactured at Pioneer Iron Works, in Consuelo, San Pedro de Macorís, Dominican Republic, 2025.

Photo: Joshua Jelly-SchapiroIn a nearby hamlet of cane-cutters called Batey Alejandro Bass, I spoke to a pair of teenagers who had no idea who their home’s name references, and to an older man with a Haitian surname who did. “El fundador!” he cried, with little evident animus, before telling me that the going day rate for cutting cane here—now bound for mills run by Central Romana—is 300 pesos (about $5 U.S.). But the legacies of the men who founded the sugar trade here are larger than this batey bearing their name. And back in San Pedro de Macorís, at the city’s library, I found a local historian and poet who’s been studying those legacies with local kids.

Hilario López Zorrilla had dark skin and smiling eyes, and is an expert on the Afro-Caribbean carnival that’s been key to his province’s culture ever since William Bass hired the first cocolos to work its fields. He acknowledged the vexed history of sugar and of the racism that’s long shaped that industry here, and spoke with expansive nuance about its founders’ role in both. “These men are a part of our history,“ López said. “And our history is inseparable from sugar, whether we like it or not—and I like sweet things!” He laughed. Then he described a hope for the young people he mentors. Its sentiment could also apply to the occupants of the Basses’ old Iron Works in Brooklyn: “It’s up to us to build, from what they left, something new.” ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast