My Ballroom Story

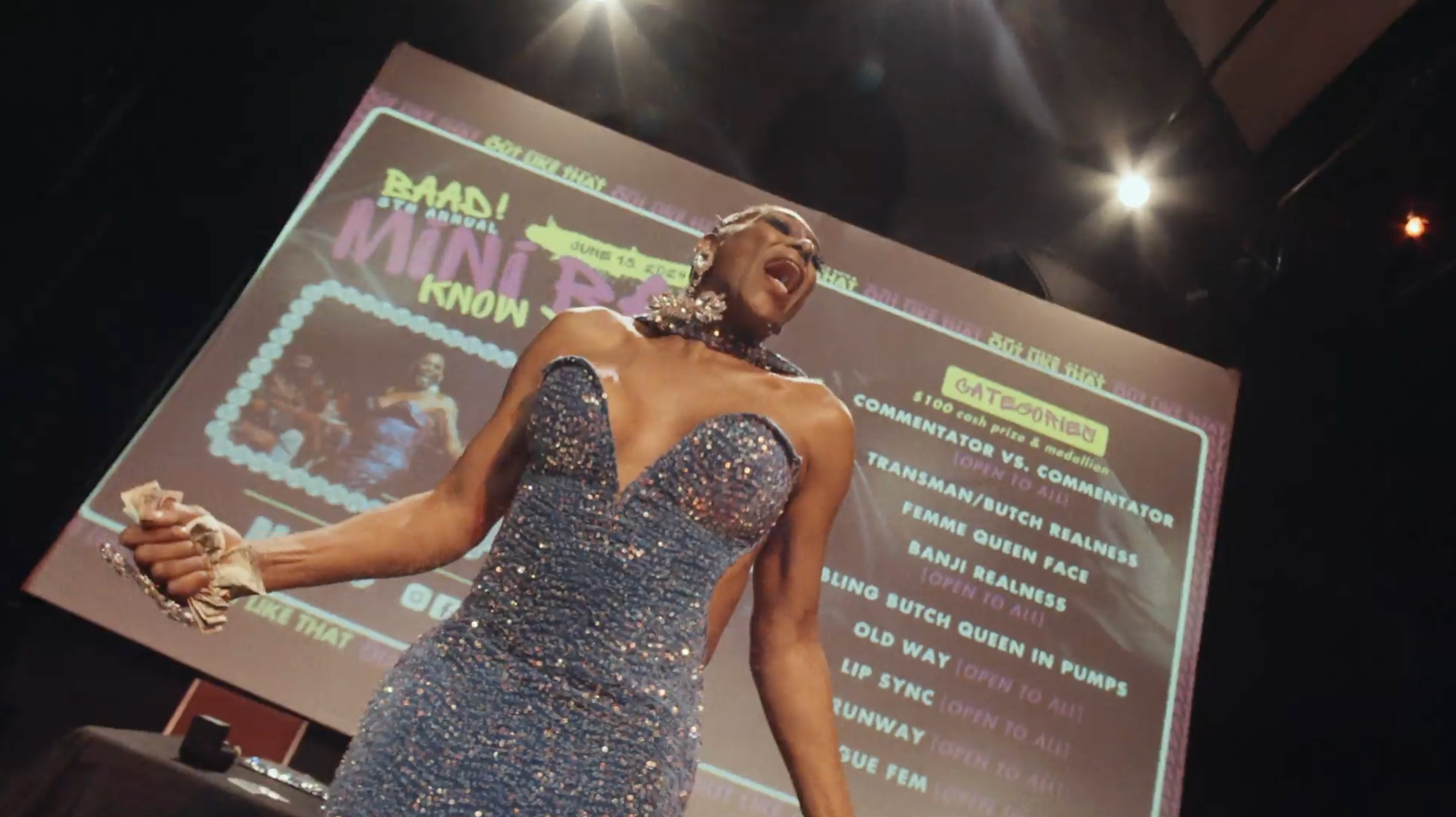

Still from Felix Rodriguez, 30 years of Ballroom Commentating (2025), two-channel video installation, 2:51 min.

Courtesy of Felix RodriguezBefore entering Felix Rodriguez’s exhibition “Legendary Looks: My Ballroom Story,” I read his words on the wall: “From the moment I stepped into my first ball, I felt an energy so powerful it was as if my soul had found its rhythm…” I teared up—not from sentiment, but recognition. That ache of finally finding home after an adolescence spent in fear and camouflage. For the gay, the queer, the gender-nonconforming, ballroom isn’t just a subculture—it’s shelter. A stage. Survival as spectacle. In the ballroom world, the very traits that once marked outcasts as targets—flamboyance, femininity, audacity—become currency. Affirmation. A self-made spotlight for kids who were once left in the dark.

Rodriguez has spent the past three decades documenting the ballroom scene as a member of the House of Milan. Known for its high energy and hyper-stylized culture and terminology, the scene is composed of “houses”—groups of chosen-family—that compete in drag tournaments, or balls, by “walking” in different categories. Rodriguez began filming balls in 1992, after watching Paris Is Burning in a theater full of people who didn’t understand what they were seeing. The laughter was wrong. He could feel it. So he picked up a camera.

His archive is unlike any other—not just for its longevity, but for what it listens to. Rodriguez follows the commentators—the MCs, the ones who carry the floor. He gives equal weight to the spectacle and the sound. The language that lifts or cuts. In ballroom, commentary isn’t background—it’s structure. A dazzling, ruthless, exacting public education. Junior LaBeija. Melissa Extravaganza. David Ian Xtravaganza. Kenny Ebony. Jack and Selvin Mizrahi. Precious Basquiat. Snooki West. Undercelebrated talents that created iconic terms and concepts such as “vogue,” “werk,” and “you better werk.”

Rodriguez has tracked the evolution of the mic with near-obsessive clarity—tracing shifts in tone, rhythm, and how authority is performed across generations.

This exhibition opens just a fraction of the archive. The three works form a living lineage—past and present in dialogue—offering an insider’s view of a world made visible through identity play and radical self-invention. In this interview, Rodriguez reflects on what ballroom gave him: a voice, a purpose, a world apart from his daylight life—where the hidden parts of him could thrive.

How old were you when you first stepped into the ballroom community? How did you find that scene?

The first man I kissed was from the ballroom scene. His name is Angel, and he was a Magnifique, years before he joined the House of Milan. This was in October 1990, I was 23 years old and had just come out as gay. Voguing was popular because of Madonna's “Vogue” video. It was also the same year as her Blonde Ambition tour. So I knew that there was this thing called voguing, but I didn't know where it came from. I didn't come out until grad school, but when I did, the majority of the people I met were a part of that scene. So before even attending a ball, I had heard so much about it—spoken with such passion—that I felt like I already knew what I was getting myself into.

One Friday night, I saw Paris is Burning. On the following Sunday I went to my first ball: the Xtravaganza Milan War Ball at Sound Factory. It was music, it was dance, it was theater, it was competition. It was call and repeat. It had all the things I loved in one place. It was the epitome of New York in the ‘90s, and it was mainly people of color: Black and Latino. Looking back at my videos of balls from 30 years ago, I’ve noticed that I liked to feature Latinos. Being the Puerto Rican Black man that I am, I felt like it was my duty to make sure they got credit in a mainly African American scene. So for this exhibition at Pioneer Works, “Legendary Looks,” I made sure to feature two Latino ballroom commentators that people rarely mention today: David Ian Xtravaganza and Melissa Xtravaganza. They were one of the first to emcee to the beat. They were celebrities in that community. But unlike Madonna or a Kardashian, you could actually touch them. It was attainable. I could become legendary, if I wanted to. I never competed though.

Never? Not once?

Never. I didn’t have the guts. I’m glad I didn't because I wanted to record the ballroom from a neutral point of view. By competing and being more involved, I would've been looked at differently. So while I never competed, the excitement of a ball would turn me on immediately. Even today, at 58, I still feel that energy.

And so you immediately joined a House, or how were you inducted?

I was always hanging out with either the Milans or the Xtravaganzas. They were considered sister Houses at the time, so they planned balls and partied together. I hung out equally with both of them. In ‘93, right after a ball that I recorded, I went to an afterparty. This was on my birthday. I was hanging out with the father of the House of Milan, Roger, and I jokingly say to him, "The Milans asked me if I'm an Xtravaganza, and the Xtravaganzas asked me if I'm a Milan because I'm hanging out with both of y'all, and nobody knows the connection." And he's like, "Well, do you want to be a Milan?" And I said yes. He's like, "Happy birthday, Felix. You're a Milan."

Who is the typical inductee?

It's usually a person who competes and has a reputation in a certain category.

I see.

But there's also other reasons why people would join or bring you into a House. Roger was very strategic. He had all the resources. He had DJs, club promoters, realtors. We were living in a time when none of us had easy access to apartments. So he had all kinds of people to service the House—and also himself on a personal level. He had one or two white girls; he’d say one of them was his wife in order to get an apartment. He had drug dealers, he had prostitutes, he had pimps. All of them were a part of his House because it was part of that underground world. So, why not throw me in, the camera person?

He even was honest when he brought me in, saying, "The good thing about having you in the House is I don't have to go to a ball because you're going to record it. You're going to capture every nook and cranny.”

Back in those days, you prepared. Now you don't have to prepare all that much, because they have balls all the time. But back then, they were every three or four months. You’d prepare for the next one based on what people did in the previous ball. So they would look at my tapes and study them. So again, he was strategic.

Like a football team, rewatching the plays.

They take it very seriously. Voguing too. They see the steps, and they try to either top them or come up with something completely different that's going to impress the judges. But there was also the fact that I was a master’s student in dramatic writing at NYU, which was something they desired. Unfortunately, a lot of House members hadn’t even graduated high school. So I was also respected.

I'll also add that when I came out, I was so new and impressionable that I wanted to vogue and wear scandals to the club.

Scandals?

Scandals is the term they use when a person wears a g-string or pumps or sequins, or mesh. They'll say, "Tonight, I'm going to go in a scandal."

So I tried wearing a scandal a couple of times, but all the queens said I was butch, and had to be banjee. "Don't be cunt, be banjee." And I was like, "Okay." It did help me get laid. Which was a priority at 23, as you can imagine.

Still from Felix Rodriguez, 30 years of Ballroom Commentating (2025), two-channel video installation, 2:51 min. Courtesy of Felix Rodriguez.

Still from Felix Rodriguez, 30 years of Ballroom Commentating (2025), two-channel video installation, 2:51 min. Courtesy of Felix Rodriguez.

Still from Felix Rodriguez, Classic Vogue (1992), video compilation, 7:31 min. Courtesy of Felix Rodriguez.

Still from Felix Rodriguez, 30 years of Ballroom Commentating (2025), two-channel video installation, 2:51 min. Courtesy of Felix Rodriguez.

Still from Felix Rodriguez, 30 years of Ballroom Commentating (2025), two-channel video installation, 2:51 min. Courtesy of Felix Rodriguez.

Yes, and still is in some form.

Exactly.

So you were studying dramatic writing, but then got into film?

They actually had a course on writing for film, and one of its requisites was to use a camera—even if you didn't have any filming or editing experience. When you're writing for film, you actually have to imagine the first shot, the second shot. How are you going to cut that? So, I grabbed the camera and never let it go. I fell in love with recording and the process of editing. I've always loved music. The first video I ever edited was Classic Vogue (1992), the one you see before you go into the gallery. It was funny because the Milans would ask me to sit at their table, which I would for like five minutes. But after a while, I’d get really antsy and want to record. I'm grateful that that’s what I wanted to do, because now you have a generation that’s gone. This was in the early 1990s, when I was working for FX. I've always tried to keep some kind of stable job while I was recording these balls. The company launched in New York in 1994, and by 1995 I’d say 90 percent of the people that I met had died, including my first boyfriend. It was devastating. I didn't think that I was going to make it to 30.

I remember one day I was talking to the company’s HR, and they’re giving me this spiel about 401(k)s, saying, “When you retire, you'll get this money back." And I replied, "When I retire?” “You know, when you're 62, 67, whenever you decide to retire." And I thought to myself that I was never going to get there, even though I was practicing safe sex—which a lot of people were doing and still getting sick. It was just a matter of time. We think we know how long we’re going to live, but we really have no idea. I’m blessed that I’ve made it this far, and I’m blessed that I recorded those balls and kept all that material to show the world. But I was recording because I knew that we were all going to die—including me. And I just wanted to make sure that that stuff was out there. If it weren't for these tapes, most people would never know who the founders of these Houses were, because there was no documentation. Watching Paris is Burning inspired me to continue recording these events.

The press materials for your exhibition mention that you saw people laughing at inappropriate times during the film.

The screening was at Film Forum. And the audience was pretty much all white. I remember distinctly when Freddie Pendavis is speaking, and says something like, "I'm his protege. If I weren’t there then he’d be wrinkled." People were laughing at him, and I thought that that wasn't funny.

They're laughing at the cultural differences, instead of at jokes?

It felt very voyeuristic. Like an outsider looking in. So I wanted to offer a view from the inside.

How do you feel about that film, and all that it’s accomplished?

It changed my life—literally. I was studying dramatic writing; I wanted to be a filmmaker; I wanted to tell stories. And even though it wasn't done by a person of color, Paris is Burning was about people of color that I knew. It was talking about music and a culture that we don't usually see in a documentary. It was like a celebration of that world, even though it was very, very dark.

What was the scale of that world like in the ‘90s? Were there thousands of people at a ball?

No, no. You'd be lucky if you had 300 people.

It's actually so small relative to how much of a phenomenon it became. But it’s not so dissimilar to the history of performance art, which was mostly just these very small moments. If you were to take a broader look, what do you think the ballroom scene gave you as a young person, in terms of your later development and growth?

Coming out in New York in 1990, I felt like there was no other place where I could ever witness what I was witnessing. I literally went to Sound Factory and Madonna was dancing right next to me. And at that point Madonna was the biggest star in the world. So to come out in New York, experiencing this whole world, felt like it was only happening there, at that time. I'm sure everybody that comes out in a big city feels the same way, regardless of the era, right?

I don't know about that. That's pretty special.

New York at the time was very club-oriented. Now you don't hear about them as much. Ballroom also changed. It became more popular, but then a lot of people in the Houses weren't going to balls. They were going to clubs instead. So then the scene became divided, between Houses that went to clubs and Houses that went to balls. Even within Houses, some would go to clubs and some would compete in balls. So we would make fun of the Houses that didn't compete. It would be like a baseball team that didn’t play baseball. How can you call yourself a House if you're not walking at balls or going to them, right? So we used to have an issue with that. But then people would have an issue with me, because they'd be like, “How can you consider yourself a Milan when you've never walked?” There became a politics of what it meant to really be ballroom. I would get so wrapped up in it, but then people would look at me and be like, well, can you vogue? So then I would shut up.

They're very protective of their world, which has also made it difficult for a lot of people in the mainstream to join in, because, again, this was like a private party. Ballroom started uptown, in Harlem, in the ‘60s, when it was illegal to be in drag. They would do them incognito in bars that closed at three o’clock in the morning. The ball would start at five am, because that was the only time that they could perform these events. Gays were considered the lowest of the low. Imagine being in Harlem at 11 o’clock in the morning after a ball had ended, and seeing so many queens parading out of the club wearing all these outfits and boas. It was a different time.

Still from Felix Rodriguez, 30 years of Ballroom Commentating (2025), two-channel video installation, 2:51 min. Courtesy of Felix Rodriguez.

Still from Felix Rodriguez, 30 years of Ballroom Commentating (2025), two-channel video installation, 2:51 min. Courtesy of Felix Rodriguez.

Still from Felix Rodriguez, 30 years of Ballroom Commentating (2025), two-channel video installation, 2:51 min. Courtesy of Felix Rodriguez.

Still from Felix Rodriguez, 30 years of Ballroom Commentating (2025), two-channel video installation, 2:51 min. Courtesy of Felix Rodriguez.

Still from Felix Rodriguez, 30 years of Ballroom Commentating (2025), two-channel video installation, 2:51 min. Courtesy of Felix Rodriguez.

So how did this Pioneer Works exhibition “Legendary Looks” start?

So, it's three different organizations doing exhibitions around ballroom culture, as part of this whole “Legendary Looks” project. There’s ArtsWestchester, which is just costumes. Pioneer Works, which features my videos specifically about commentators, and then City Lore, which includes videos, but also flyers. Michael Roberson, the exhibitions’ organizer who’s very involved in ballroom, suggested my videos for Pioneer Works. For a theme, I wanted to focus on the commentators, because I've seen how that role has changed over the last 30 years. If you don't have a good commentator, you might as well not have a ball.

When you took me to the Latex Ball, what I remember most were the commentators’ catchphrases, which have stayed with me for the past 10 years or so. "Gim-me, gim-me, gim-me, my life back." Another emcee used the word "Trace." He would shout out a category, such as Butch Realness, and then shout "trace, trace, trace, trace. I loved the concept of tracing an identity. It was immediately clear to me that emcees are crucial. They are masters at keeping the energy high. In the exhibition, you’re able to go through this audio archive and listen to them side-by-side, which is something I’ve never seen before. It's an amazing resource. What are some other structural differences?

In the early days, people were voguing to music. Now they vogue to the commentator. The commentators are telling them what to do and the walkers are literally moving to their sounds and riffs. The commentator is not only hyping up the audience, they're also hyping up the competitors. A testament to how much balls have grown now is people get thousands of dollars in prizes. Back then they only had one cash prize, and it was given to the House with a production. At the end, there was always the Grand Prize. You were lucky if you got $150. Now you walk one category and you get $3,000 or more.

Oh, really? I didn't realize.

You have sponsors now—cosmetic companies, Fortune 500 institutions—that are pouring money into these balls because that's the thing to do. Pride was sponsored by Citibank and Chase. So people in the ballroom scene took advantage of that and are making money.

That was unimaginable when you began?

Yeah. The few people that are still around from the ‘90s are upset because they feel that ballroom’s history has been forgotten. People make too much money. There are no longer Houses. People don't get together anymore because everyone's on social media. The older generation doesn't like how the world has changed, particularly in the ballroom scene. Especially outside of the United States, you have Houses now that were created in dance studios. They've never had a mother or father in the way that we experienced them when we were younger. These Houses are basically just a club that competes at balls that they learned about in a dance studio, whereas in our generation you learned how to vogue on Christopher Street, on the piers. You learned it at the club. You went home and studied that tape. Now you go to a class.

So when you see your installation 30 Years of Ballroom Commentating (2025)—which projects footage from a ball in the 1990s alongside footage from one in 2025—what’s it like seeing the passage of so many decades, side-by-side? I could definitely see RuPaul's Drag Race’s influence in the 2025 footage. The looks are more fantastical, and not rooted in reality. But what's your take?

When I look at the ‘90s it's really nostalgic. Because again, the majority of those people are gone. But I respond to it more because that's my generation.

The ‘90s looks are amazing. They’re hot and beautiful. And while the energy between the two eras is the same—the spontaneity, the bravado—the style is markedly different.

One of the things that they were trying to do in the '90s was assimilate into heterosexuality. Trans women wanted to look like women. They didn't want to look like drag queens. They wanted to be able to get on the subway and pass. So the fashion was street fashion. It was like, no, I'm not going to look like a RuPaul’s Drag Race competitor. I want to look like Marisa from the bodega.

That’s the pain and the beauty of it: wanting to be part of a world that doesn't want you, and still wanting to own that space and claim it and be it. I have an artist friend who uses voguing in his work, and he said that there's an element of Stockholm syndrome to voguing that people don’t want to talk about—because we want to celebrate its creative expression. There's a sadness in needing to emulate this world of the upwardly-mobile professional at five o'clock in the morning, hidden away in a closed bar. It’s a world that’s unavailable to you.

These were people deprived of an education and a career—something that would allow them to leave the hood. So the only way they could do it was by emulating what they considered to be a rich person: driving a certain car or living in a House that had five rooms. Of course that’s attractive to somebody from the projects. So they can only dream—and a ball is the place where those dreams can come true.

That also creates a certain kind of rigor. If they only have a moment for them to live their fantasy, it puts pressure on them to be precise.

There's an argument to be made that a lot of those same people could’ve been more successful in life if they had put all that ballroom competition energy into getting a job or going to school. They spent so much time preparing for balls that they didn't do anything for their careers.

Installation view of Felix Rodriguez's Legendary Looks: My Ballroom Story at Pioneer Works, June 8-August 10, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Pioneer Works.

Photo: Dan BradicaInstallation view of Felix Rodriguez's Legendary Looks: My Ballroom Story at Pioneer Works, June 8-August 10, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Pioneer Works.

Photo: Dan BradicaWell, but in the ‘90s those careers just weren't available to them.

Right.

In the arc of time since you began, ballroom has come to dominate queer culture. Its visibility and celebration in the mainstream have helped shape a broader understanding of gay identity, contributing to the progress and empowerment of LGBTQ+ lives over the last three decades.

Gay and trans people have degrees and own their own homes and travel the world. We've arrived. Why would I spend all my energy now in competing for a trophy when I can be putting that energy into…

We don't have to pretend to be the thing.

We are the thing. The world has changed a lot, but it also hasn't, right? So there's definitely still a lot of racism. We still lack access to as much as we’d like. And ballroom was always and continues to be a place where people can be free creatively, imaginatively, and sexually. There are still dreams yet unfulfilled. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast