Music's Living Archives

In the late summer of 2022, I started to notice mentions of Black Eyes, the beloved DC post-punk group, bubbling up in my social media feeds. At that point, the band had been defunct for nearly two decades. But photographs, flyers, and zine spreads were surfacing daily via several archival accounts on Instagram—feeds full of scene-specific, niche nostalgia of a kind that became hugely popular during the pandemic. Not only were these accounts sharing Black Eyes ephemera; longtime fans and band members themselves were reposting and commenting on the pictures. It was like the band was having a second life. And before long, they were: earlier this year, we learned that Black Eyes is reuniting, almost 20 years since their last show at DC’s Black Cat in 2004.

Until then, it had never occurred to me how alive an archive could actually be. Not alive as in, looking back on something with sentimentality, but as in mid-sentence, a wheel still turning, a piece of driftwood that is able to catch fire once again. It dawned on me how this reunion, this sense of purpose rekindled, had been set in motion, at least partially, by the ephemera of its inception. How the polaroids, flyers, set lists, zines, live recordings, and albums were not just static objects to be referenced and dissected; these artifacts were actual open doors. The Minutemen’s Mike Watt once said that he and his bandmate D. Boon had placed everything they did into two categories: gigs and flyers. “So everything that wasn’t a gig was a flyer to get people to the next gig,” Watt said. “Even records.” In this light, I began to think of archival work as a conversation, a rope across time, a window into past selves; collective blueprints not just to the next gig, but to a different world.

This was not my first encounter with the world of music archivists on Instagram. By 2022, I’d already been following a number of them: @there_is_no_planet_earth, which documents queer histories of house, techno, and ballroom music; @punks_berlin, which covers punk’s early European influences; and @postpunkproject, which is dedicated to goth and new wave-tinged music strains (and which, just before the publication of this piece, rebranded as @newwavesocialclub). As these pages grew in popularity, I grew intrigued by their meaning. Were they true archival projects—genuine, systematic efforts towards preservation? Who were the people behind these accounts? Were social media metrics and metadata affecting their work? Was this content being backed up anywhere? Some of these pages function like repost accounts, Instagram blogs which share the types of material that once may have decorated a high school locker or Tumblr page. On others, watching connections generated in the comments section carries some of the old appeal of message board culture, fanzine classified sections, or even long-lost penpals.

Archival accounts on Instagram are embedded with contradictions. But beneath the algorithmic churn, real discussions are happening, enabled by the platform’s relative accessibility and ubiquity. On Instagram, new devotees to forgotten subcultures are shaping living memories in real time.

*

Who exactly are these Instagram archivists? By 2023, online habits and interests have become at once more eclectic and varied and, simultaneously, more centralized around the bigger social media platforms—specifically Instagram and TikTok. In the late 2010s, editors of online publications saw visits to their homepages plummet as audiences found their way to news and information not by navigating to their favorite websites, but via links in their social media feeds. In response, these platforms moved to keep readers on their sites, inadvertently creating an environment where engagement around news and information—such as archival materials—thrived in interactions and impressions. Did the business objectives of these platforms unwittingly give birth to a new wave of music information fetishists—or was there something bigger at play?

For the discerning music fan, Instagram provides multiple points of entry to each genre. Electronic enthusiasts can audit a course celebrating the Black roots of dance music through the University of California-affiliated page @blacktronika; find a unique portal into ’90s global techno through @technique_tokyo, the last bastion of the beloved record shop which shuttered in the pandemic; or discover out-of-print underground house music at @localhouseplug. Within punk, @50ftqueenie gives a feminist lens on post-punk and indie music; @sceneinbetween is for retro mod sounds and influential ’60s styles; and @umdpunkcollections offers a spotlight on the genre’s DC-offshoots. And then there’s @bipoc_punk, a popular page highlighting marginalized voices across punk history. Many of the pages have amassed followings ranging in the tens of thousands, while some are much larger, like @dusttodigital, which is arguably the most popular music archive account, and closing in on a million followers.

@bipoc_punk’s founder Raymond Lacorte, a lifelong record collector, was shocked by how little even his most musically knowledgeable friends knew about the BIPOC roots of new wave and post-punk. Having grown up listening to alternative music on Manila’s DWNU 107.5, Lacorte was long a champion of Filipino bands like The Dawn and Third World Chaos. His early Instagram posts drew on what he’d gleaned over the years from local DJs, friends, websites like No Echo, and radical publications like Shotgun Seamstress. But the more the page resonated, the more conversations took off: “I've been learning along with the followers,” Lacorte explains to me over Zoom. “Even to this day, all these requests [for more acts to feature] are just new bands to me too.”

Similarly, DC punk luminary John Davis—formerly of the bands Q and Not U, Georgie James, and Title Tracks—watched his page quickly grow into a breeding ground for conversation and knowledge sharing. After performing in DC’s underground music scene for decades, Davis embarked on a new career as an archivist, and now finds himself running the account @umdpunkcollections—the Instagram arm of the DC Punk Collection at the University of Maryland’s performing arts library. Like the archive itself, the page—which he began in February 2020—chronicles ’70s and ’80s punk, as well as the lesser-opined subgenres of the ’90s and early ’00s, through photos and flyers from historic venues like the Wilson Center, DC Space, and All Souls Church. “I've always had a collector's mindset,” Davis tells me over Zoom, who from a young age saved flyers from every show he attended.

Davis used to avoid Instagram, but eventually found it useful as he began work on a book about the history of DC punk fanzines. “There are so many people whose email addresses can’t be found anywhere, but you can find them on Instagram or Facebook.” The page’s comments have become like a forum, with followers discussing shows, or who designed flyers, or tagging friends who were there. “That's cool to me,” Davis reflects. “Just reconnecting people with these moments that were important to them and hearing more of those stories.”

Davis was a member of Dischord Records-affiliated post-hardcore act Q and Not U, and he has long viewed music and archiving as intertwined—in part because mentors like Henry Rollins of Black Flag and Dischord-founder Ian MacKaye (of Minor Threat, Fugazi, Embrace) both kept meticulously detailed archival collections. “We became friendly with Henry Rollins in the early 2000s, and he put us up a few times at his home when we would pass through Los Angeles,” Davis explains. On one of these visits, Rollins showed the group his vast and painstakingly organized DIY archive of recordings, correspondences, photographs, and scrapbooks. “He's not connected to any institution at all. He's just saving this stuff because he thinks it's important, and that eventually people will be able to use this for research or inspiration.”

*

Much like the viral cooking accounts that preceded them, the music archives of Instagram preserve the recipes of their favorite subgenres through sharing little-known information that elucidates the music, from lesser-known acts and playing styles to historical contexts that lend certain moments significance. Unaffiliated with any institution, the administrator of @there_is_no_planet_earth—a page which documents queer dance music histories in New York, Detroit, and Chicago—emphatically embraces this historical context.

Run by DJ and self-professed “archive queen” Ben Manzone, @there_is_no_planet_earth began with Manzone’s voracious appetite for consuming analogue and digital culture. “As a DJ and lover of this music, I felt like it was my responsibility to educate myself about what I'm involved with,” Manzone tells me over a spotty Google Hangout feed. “I've been a DJ for the past 20 years in New York, so that Instagram page is really a culmination of the past 20 years of research and collecting media. Emptying my YouTube favorites, SoundCloud likes, Mixcloud likes, things I saved from Tumblr days, plus the fact that I am gay and [value] researching, being a part of, and studying gay history and culture. I'm a person who appreciates reference points, and knowing the gay history interests me. I think it's important to know.”

Manzone’s early education in dance music was mostly online, through an early-’00s archival web page called Deep House Page. “I'm so fortunate for that page, because I learned so much,” Manzone admits. Nowadays, one can easily google mixes from seminal DJs like Chicago house music pioneer Ron Hardy or the infamous DJ Mojo (who is said to have introduced Kraftwerk to an early electronic music-loving Detroit). But in the ’90s, these cultural artifacts were harder—if not impossible—to find outside of tight-knit communities.

As a stand-alone website, Deep House Page was a dance music destination, hosting a hallowed archive of mixes, full of legendary moments. Its clips covered all of the major players from the early ’80s through today, from Larry Levan of New York City’s Paradise Garage to DJ Frankie Knuckles at the Warehouse in Chicago (house music’s namesake venue). The website’s forums frequently featured nightlife royalty—everyone from The Loft’s David Mancuso (whose invitation-only parties helped inform a generation of nightlife promoters) to Paradise Garage regular François K—answering questions from discerning listeners in real time. “I got into the forums because I was doing track IDs,” Manzone explains. “This was before Discogs and YouTube. Your sources for research were really limited. And so I would just go on those forums and track ID, and that's how I met a lot of people in those earlier days.”

Manzone was also fascinated by the archival stylings of Nelson Sullivan, a gay icon and videographer who taped his life in the ’80s downtown scene, taking his camera to the Pyramid, Danceteria, Mars, and Limelight. When Sullivan died of a sudden heart attack in 1989, his contemporaries secured a permanent home for his more than eleven hundred hours of footage at the Fales Library and Special Collections at New York University. Fortunately, there is also a vast body of his work available on YouTube. A self-identified Sullivan expert, Manzone has hosted screenings of his videos around Brooklyn, and spent hours combing through the Fales footage in hopes of one day making a documentary. It was when his attempts to secure the necessary rights to do so hit a dead end, in February 2021, that Manzone instead channeled his fixation into @there_is_no_planet_earth.

The Instagram page launched with little fanfare, until an early cosign by underground house music titan and Beyoncé-collaborator Honey Dijon cemented @there_is_no_planet_earth as a must-follow account. “[Honey] was just amazed,” Manzone remembers. “She was like, ‘Wow, you have all the receipts, there's stuff I've never even seen before.’ And she would repost my stuff. That was the start of the flood of people following my page.”

Manzone, like Davis, sees the comments on his Instagram account working like message boards, helping to fill in the gaps in his own knowledge: “People reach out to me in DMs, some of the older crowd, and they're like, ‘Did we ever cross paths? Do I know you?’ And I'm like, ‘No, not exactly.’ But for the most part, when I explain where I'm coming from, and the Nelson Sullivan thing, people are like, ‘Wow, this is really cool. I respect what you're doing.’” The followers and their stories help to paint pictures that transport him to a different time and place. “I like when people are telling me their personal Paradise Garage stories or whatever. I posted a B-52's song, ‘Mesopotamia,’ and someone wrote this whole thing about how whenever that got played at the Garage, Moi Renee, who did Miss Honey, would do a whole show to it on the floor.”

The site that was once Manzone’s go-to, Deep House Page, changed hands a few times before it suffered the same fate of many early internet blogs and archives, and was altered beyond recognition by 2015. Learning from the past, Manzone keeps a hard drive of all the material he posts on @there_is_no_planet_earth, so that all of his saved YouTube videos and Mixcloud files aren’t lost to the entropy of the evolving internet. According to Manzone, this is one of the biggest reasons he started the project: “So much of the stuff I post is stuff that I ripped for safekeeping because I didn't think it was going to stick around for too long on YouTube. And rightfully so, because a lot of stuff that I have isn't on YouTube anymore.”

Others, like Lacorte, of @bipoc_punk, let their digital cards fall as they may, by keeping their records solely on Instagram. “The only real record keeping I have is just a very finite list of artists I have started to keep,” Lacorte says. “I would say that if it gets hacked or lost in the ethos, that's it—it will be something that I just have to kiss off. It's one of those things that maybe makes it even more valuable, I suppose.”

*

While Instagram archivists may share ethos and motivations with their counterparts in libraries, most don’t see their work standing the test of time. Perhaps jaded by the sandcastle legacies of internet archives before them, Lacorte sees his contributions as inconstant, and celebrates this aspect. Others, like Manzone, are keeping their own backups in case they one day have to move their archive to the next dissemination platform. Why then put so much work into something that feels so ephemeral? And what can these archivists do to protect their work?

John Davis, who has come to cherish his relationship with the University of Maryland, encourages anyone pursuing an archival project to build a relationship with an institution like a university or a library (even if libraries like Maryland’s backup their files on servers owned by Amazon). While your selfies from 2010 might be preserved today, there is no guarantee they will be tomorrow. Instagram has been known to delete user accounts without warning and without returning their data. Its terms of service state that the company has carte blanche over which accounts it can deactivate. “It can go out of your hands immediately,” Davis says. “Who knows what could happen if you're just trusting Instagram to be the protector of your materials?” Davis is fortunate to have the backing of a noted research university and its librarians, but for those just starting out, he has advice: “We're in a new world now in terms of how to maintain a digital archive. It is tricky. I would hope that someone who's running an Instagram archive would also maintain it in a couple of other places, that they keep the files, that they keep the metadata, whether it's a cloud or hard drive storage.”

Concerns about the longevity of files aside, Instagram’s user interface and prioritization of decontextualized short-form content also creates limits to what archivists can do. In Manzone’s case, those limits encompass the very essence of what his archives are trying to preserve: long-form mixes and audio. “I'll often post clips from a mix I like. Sometimes it works and it's cohesive, and other times I'm like, ‘Why am I cutting one minute clips of two-hour DJ sets?’”

He’s still looking for support for his broader project, which has grown to also encompass art shows, installations, video production, and radio shows (including a regular spot on the London-based Defected Radio). For now, Instagram is an ideal testing ground for his digital hard drive collection. As a gay archivist, Manzone views his work as a public service to the greater LGBTQIA+ community, especially when it comes to preserving the legacy of those killed by AIDS, through sharing “actual firsthand accounts” of history: “There are very few voices to actually recount this stuff for many reasons. The biggest reason is AIDS decimating a good chunk of that crowd, and that goes even to the early Chicago house days. The vast majority of that scene is not with us anymore. So I think we need this oral recounting of this stuff in the comments, for people who were actually there and can speak on it.”

For Davis, the goal has always been to keep the archive alive, as a thriving, growing, changing piece of culture. “The goal is to not be a time [capsule] but to be a place of creation,” Davis says. “Like with zines, it’s about spreading the word; it's about giving people a space to be heard, and for other people to come and hopefully connect to those things and learn from them. To be inspired by them, and then to go out and do stuff.”

*

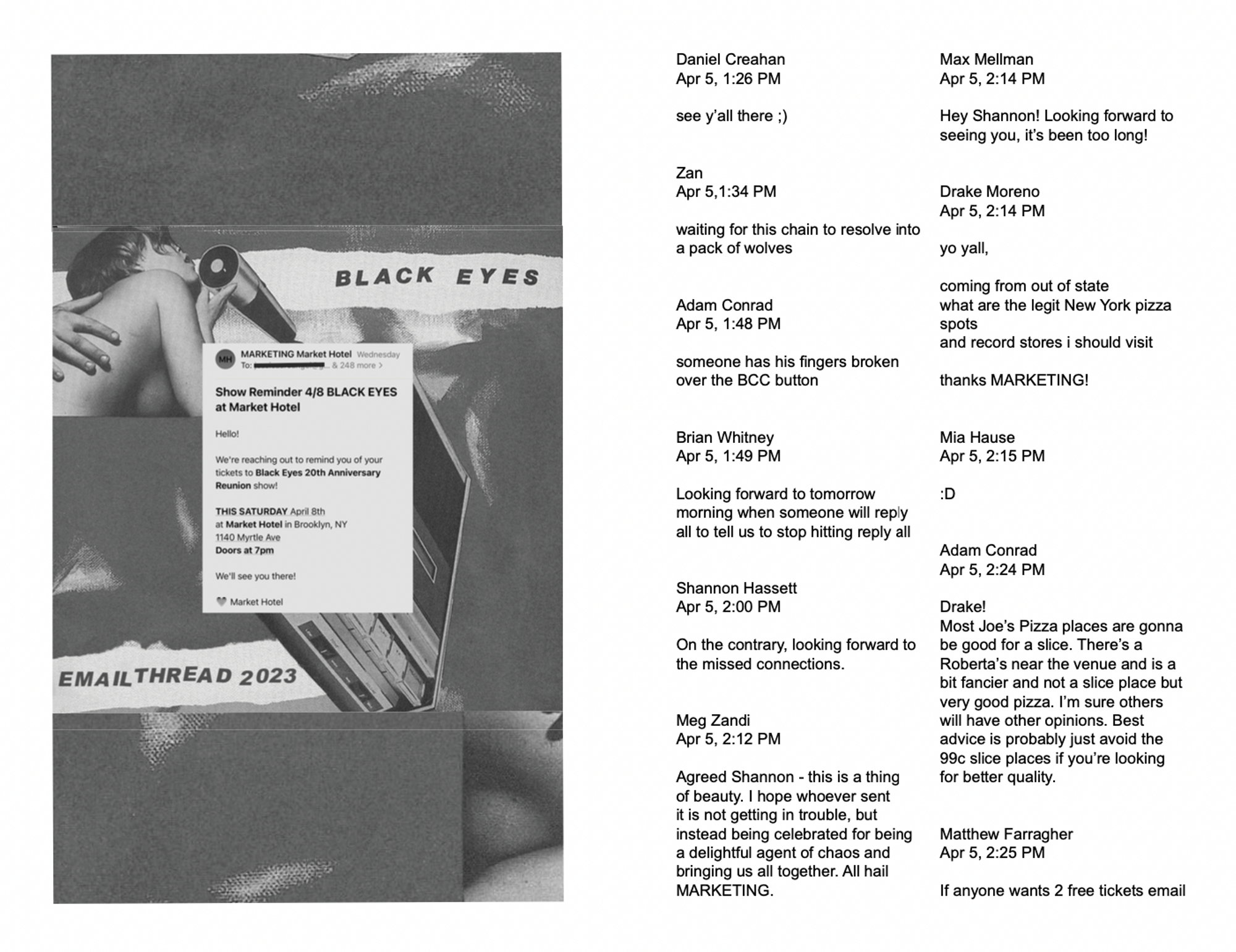

The fateful Black Eyes reunion tour did eventually happen, bringing the reformed group to Brooklyn’s Market Hotel in April of this year. Three days before the concert, the venue sent out a standard pre-show email reminding ticket holders of the address and door times—but accidentally cc'd all 250 ticket-buyers, making their addresses visible in the thread. Suddenly, the Black Eyes fan base was galvanized once again, transported back to the days of message boards and DIY pen-paling with a simple “Reply All.” Beginning with sardonic acknowledgements of the platform that Market Hotel had inadvertently created, the thread quickly calcified into earnest totems of fanlore and archival work, into sharing ideas and spare tickets and couches to crash on. It was like a return to online behavior from a time before Instagram. While the venue tried in vain to dissuade participants from further “Replying All,” the response from the thread was a unanimous “No.”

At the show, old friends were reunited—some for the first time in decades—while new friends who had just met on the event’s email chain gathered and exchanged glances and numbers for the first time. A friend and DIY lifer, Zan Emerson, used the email thread to invite out of towners to crash on their couch if they needed a place to stay. The night before the show, they also took the initiative to further cement the thread’s legacy, transforming it into a zine that they distributed at the event and online. (It’s still available on their portfolio website.) Will a photo of the zine eventually become a square grid post on a punk ephemera social media page? Only time will tell. At that moment, what was given extra life in memories and on Instagram had come back to its original form, resurrected in a zine on the eve of Easter, where all of those who had passed zines around in their early twenties could finally have a voice again, at least until the papers shriveled and browned and the platforms faltered and failed to live up to their former glory. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast