Library Music

A discussion of publicly funded streaming alternatives gripped a meeting of the Union of Musicians and Allied Workers earlier this year. “We were talking about a lot of strife that most people feel with streaming, and how it feels like it's not really serving artists,” recalled one member, Rachel Steele. “It's serving the powers that be, whether that be labels, Spotify, shareholders...” It got Steele and fellow Chicago chapter members thinking: Building something new would be complex on a national level. But what if we started locally in Chicago?

The group’s plans are loose, but they want to make something research-driven, regionally-focused, available to all, and that compensates artists fairly. “We want to reimagine and create something that really honors Chicago's collective music memory,” Steele said. “The importance of an archive can never be overstated.” They’re calling it municipal music streaming.

UMAW Chicago is exploring multiple alternatives, said Steele, a producer and artist with a background in web design. In digging through Github, she has found freely available open-source code for music streaming, and has considered trying to build something herself based on what she learns from a survey released to Chicago musicians. But what the group is most seriously considering, despite some reservations, is pitching this idea to a local public library.

*

If UMAW Chicago is successful in garnering library support, Chicago won’t become the first city with a public library-hosted local music streaming service. Around the U.S. and Canada, dozens of public libraries have launched community-driven local music streaming collections over the past decade: Seattle, Austin, Pittsburgh, Minneapolis, Eau Claire, Chapel Hill, Edmonton, Salt Lake City, and Denver among them. But to date, the existing library-hosted local streaming services have largely been spearheaded by libraries themselves. UMAW Chicago’s project would be a rare instance of such a project growing directly out of musician organizing—particularly the new wave that has erupted through groups like UMAW and the Music Workers Alliance.

Within librarian communities, the concept of local music streaming has spread through a combination of word-of-mouth, conferences, and media coverage. The majority of the projects are run like this: Local musicians submit recordings for consideration once or twice a year, during an open-call period. Then a group of curators (typically 5-10 locals deeply embedded in the town’s music scene) or library staff choose 40-50 albums to add to the collection, focusing on contemporary artists and material released in the past 2-5 years. Musicians are paid an upfront, one-time license fee, usually around $200-300 to license their record for two years. Many, but not all, of these projects are run using an open-source software called MUSICat, and in somewhat of a partnership with the two-person tech company that publishes it, Rabble. Some offer downloads, while others only offer streaming. For musicians, this introduces crucial ideas for circulating digital music: acknowledging the importance of accessible, publicly available music, but also the material reality that artists should be paid, and not on a per-stream basis.

Library-run local streaming has existed for almost as long as mainstream music streaming itself. Several librarians traced their inspiration back to a specific time and place: 2012 in Iowa City. The year after Spotify launched in the US, a now-retired public librarian named John Hiett was in a bar listening to a local singer-songwriter. He wasn’t exactly thinking about how libraries could provide an alternative to technocratic platform monopolies that exploit musicians' labor and listeners' attention—he was thinking about his CD budget, and how not enough of it was being spent locally. He thought to himself: "How come we ship all of our music budget out of town? Why don't we do more with this?"

Soon, the Iowa City Local Music Project was born. Hiett pitched the idea to the library, and the library’s webmaster happened to not have many projects lined up at the time. The library went to the City Attorney, who took on the project of developing a contract for local musicians. The library paid artists $100 to distribute their recordings for two years. It launched in June of 2012 with 58 selections, and within a week, 334 albums had been downloaded.

“It started out as something really rudimentary,” said Jason Paulios, the library’s Adult Services Coordinator, who has since taken over the project. “I took hardcopy CDs to the webmaster, and he would rip them into FLAC, and then figure out a code.” In more recent years, a new webmaster remade the library’s website in a free, open-source content management system called Drupal, and then rebuilt the Local Music Project within that website. Paulios says the backend is similar to publishing on Bandcamp, and in the spirit of sharing that seems to define public libraries, he was quick to mention their willingness to share their code with interested libraries.

Building out this infrastructure was “not insubstantial,” Paulious explained. “We built three different versions of this thing. There's very few libraries, I think, that are interested in that, or have the capacity to do that. We've always had our own webmaster, which is kind of unique with city libraries, and such a gift.”

Ann Arbor District Library was another of the first libraries to offer local streaming music—it has hosted a digital music collection since 2002, and started licensing music from local artists in 2010, including a partnership with electronic label Ghostly International. According to Eli Neiburger, the library’s Deputy Director, building the library’s own streaming and mp3 downloads infrastructure directly into its website has been an important decision. A lot of the local music material—referred to as the Ann Arbor Music & Performance Server (AAMPS)—is stored in the library’s own data center, in its basement. “It’s really not that hard to serve an mp3 or other music file,” he said.

While many libraries turn to outside tech vendors to help run digital offerings, Neiburger feels strongly about the library controlling its own digital infrastructure—an ethos that extends beyond just music streaming—and it has to do with how commercial and streamlined the internet has become over the past two decades. “The web we lost is still down there,” he said. “The early days of the web were ones where there was a lot more variety and a lot more opportunity. As you’ve seen so much consolidation over the years, public libraries are one of the few forces resisting that. So I think it’s all the more important that libraries are in control of their own infrastructure.”

Ann Arbor’s library is in a uniquely flexible place: it’s an independent government entity with its own elected board and tax, which has allowed the library to invest in its own I.T. “team, expertise, and code base,” said Neiburger. “All of the stuff that we’ve built, we share freely, any other library can use it, but very few libraries are in the position infrastructurally to take advantage of it.”

Toby Greenwalt, the Director of Digital Strategy at the Carnegie Library in Pittsburgh, said that many libraries cannot afford to build out their own digital tools from scratch. “Most libraries are running on pretty shoestring budgets,” Greenwalt explained. “The thought of doing something that requires more extensive custom software development is a pretty big lift … It's really just a question of, what are the tools you have at your disposal? And how can you make them work for you?” That is partially why his library, which launched Stacks Music Library in February of 2019, has chosen to collaborate with Rabble, using its MUSICat software.

Kelly Hiser, co-founder of Rabble, first started working on local digital collections as a Digital Publishing Researcher at the Madison Public Library. At the time, another librarian had heard about the Iowa City Local Music Project, and brought in a local tech vendor to start something similar. “I came in and was the bridge between the tech guys and the library people,” Hiser explained. She called up Paulios in Iowa City for advice, and by May of 2014, Madison Public Library launched the Yahara Music Library.

An initial review of the collection by independent music outlet Tone Madison (headline: “Is the Yahara Music Library any good?”) approached the project with both "optimism and skepticism." The author noted that similar efforts to support Madison music had “trouble connecting with all the different pockets of musicians and audiences [the] city has, and for some reason have a penchant for putting people through hellaciously convoluted online voting and sign-up systems.” Yet the review ultimately praised its “simple and clean” interface, and the fact that the initial collection spanned a wide spectrum of genres: jazz, hip hop, classical, experimental.

It was bare bones, but it was efficient, and one of those tech vendors the library had brought in, Preston Austin, thought it might be something he could help build for other libraries. As Hiser recalled: “He said, we want to take what we did with Madison and build something that we can replicate for other public libraries. Will you run it for us?” Rabble’s open-source platform, MUSICat, now powers local streaming collections at over a dozen libraries around the US and Canada.

Rabble, at first, pursued a traditional start-up route (pitch deks, investor meetings), but ultimately went in a different direction. “We made a decision not to pursue investor funding,” Rabble wrote in a five-year anniversary reflection. “Instead, we dedicated ourselves to growing Rabble and MUSICat organically.” Rabble pays its two-person team through subscription fees paid by libraries, which currently amounts to about 40% of what a library might allocate as its total budget for one of these projects. The expenditure sometimes comes straight from a library’s budget for collections, electronic resources, or databases. Frequently, though, it comes from grant or foundation funding.

MUSICat co-founders stress that their goal is not to standardize the way these collections exist. “Getting it right means that lots of people have influence over the model on an ongoing basis,” Austin said. “And that the model does not displace the ability to have other models.” He also said that the limitations of these as city-scale efforts are key: “How do you make a licensing system that’s fair for all the artists in the world? I don’t know. And with respect to city-scale licensing, I don’t care. It’s important that we don’t care. We’re saying, let’s make something better here, in a way that’s super controlled by here. That’s governance that says, actually people in Memphis know more about Memphis than people in California, and we don’t need a generic solution for the whole world in order for people in Memphis to get paid.”

*

Several librarians who I spoke with for this piece referred to their local music streaming project as more than just a collection, but as a “digital public space,” a phrase that says as much about contemporary digital norms as it does about potential futures they’re helping to build. To these librarians, creating a digital public space is as much about public-minded ownership (offering a space outside the incentives of multinational corporations and advertising businesses that define our digital lives today) as it is also about the governance of the space, and working in collaboration with local musicians and patrons to shape how it functions.

“This is not best thought of as Spotify for the library,” said Stacy Schuster, who recently helped launch a local streaming collection at the Kent District Library in West Michigan. Through KDL, cardholders also have access to two non-locally focused music streaming services, Freegal and Hoopla. But in the eyes of many librarians, the local digital collections are not just about creating a pool of streamable music, but about the connections that get formed in the process and the activity that pops up around them.

The “digital public space” framework for an online music offering can in part be traced back to Edmonton Public Library (EPL), where in 2013 an intern named Alex Carruthers was tasked with researching digital public spaces, which led her to the Iowa City Local Music Project. In order to follow the library’s broader stated mission of being a “community led library”—a practice where libraries research local needs and co-create services with ongoing patron feedback—Carruthers organized an unconference attended by over 50 Edmonton musicians. Among its many takeaways, musicians expressed the importance of a collection that was regularly updated, interactive, and curated by the community. “There was about equal interest in the site celebrating history and supporting the contemporary scene, so we decided to do both,” Carruthers wrote in 2015, calling the project’s scope “local music history up to yesterday.”

From there, EPL hosted a hackathon where local open source developers collectively came up with ideas for how to build the technical infrastructure. But the resulting models were too costly for the library. Instead, to launch Capital City Records, they contacted Rabble, who worked with EPL on its vision for not just a streaming collection but tools to make an interactive, co-created space. Rabble has since incorporated those ideas into its core product.

In Pittsburgh, Stacks embraces the “digital public space” model as well, and considers participation from local musicians to be at the heart of what makes it valuable. “This is really an opportunity for us to build something that really comes out of a true collaboration with the people we serve,” said Greenwalt. “We work with a vendor to build it, but it is fundamentally an open source tool that they just happen to manage for us. We're able to really set the tone and guide something that's a collaboration between us and the artists that we're working with.”

There have even been a few “full circle” moments, like when the band Airbrake used the library’s instrument lending library to make their recordings, and then submitted them to the collection—one Greenwalt called a “living collection.” And it opens up bigger conversations: what does it look like for a city to truly support its music community? How can the library help facilitate that? “That touches on a lot of things from funding sources to policy,” says Greenwalt. “I don't expect us to go in and effect change overnight. Really, it's about listening and finding ways in which we can effectively just serve the needs of [local music].”

*

Raquel Mann, the Digital Public Spaces Librarian at Edmonton Public Library who oversees Capital City Records, explained that its local music collection is important for all of the same reasons that its local author collection is important: local music is part of local history. “We started to realize that the traditional focus on famous authors, famous music—it doesn't really help us learn about ourselves, here,” Mann explained. As part of her job at the library, Mann also helps to coordinate a digital space for local Indigenous storytelling, Voices of Amiskwaciy. “It really is the way we learn about our neighbors,” she continued. “And really understand who lives with you, who lives in you. Where you live is really important, and local collections do that. You can't get that anywhere else.”

Three years ago, a group of Edmonton radio DJs approached the library with a large archive of interviews with local music legends. The library created a feature for community groups to work on their own projects and showcase them on the site, where the DJs can add profiles with audio, photos, and text. They’re also working on preserving histories of shuttered local venues. “It's been quite emotional,” Mann said. “There was one radio host who broke down in tears when he saw it.”

When Capital City Records was first launching, one of the local musicians who helped with early curation efforts was rapper, writer and producer Rollie Pemberton, who performs as Cadence Weapon and previously served as Edmonton’s Poet Laureate. For musicians like Pemberton, these types of local library projects sit at the intersection of multiple ongoing challenges in music: the disappearance of public space, and issues presented by the current music streaming status quo. “The problem that I have with the system is that it's inherently extractive,” Pemberton explained. “It's all about what they can drain out of the artists, what they can take from the artists.”

He also points to the mysteriousness of corporate streaming gatekeepers. “The way I think about engaging with streaming companies, it's like the Wizard of Oz to me,” he explained. “You can't see them, you don't know who it is behind these playlists, you don't want to ruffle their feathers and then never end up on a playlist. It's this kind of fear involved with the anonymity of it. Whereas, if it's somebody from your community that you actually know, there's a certain level of trust there. There's guaranteed income, guaranteed proliferation and exposure.” Pemberton also pointed out how important it is that on Capital City Records, albums are presented without prominently-listed play counts; on mainstream platforms, these metrics influence listening patterns and recommendations. “It’s having a really, really bad impact,” he says—it’s not just an issue of artist payment, but is inherently changing the way people listen to music.

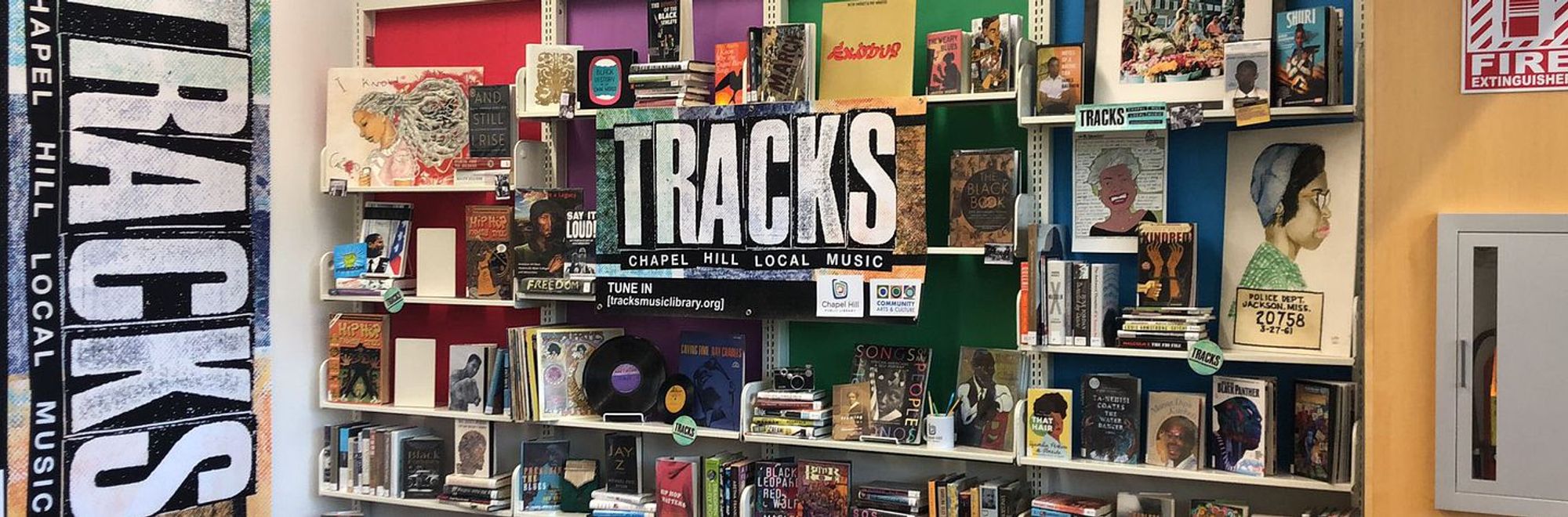

The small and localized scale of these collections could potentially be part of fostering deeper connections. Erika Libero, guitarist and vocalist of the Chapel Hill punk band BANGZZ, and also an artist curator for Tracks Music Library—a collaboration between the Chapel Hill Public Library and Chapel Hill Arts & Culture—likened Tracks to a “yearbook snapshot” of the local music scene. Another curator, hip hop artist and educator Kevin “Rowdy” Rowsey, said that when his album Black Royalty was included in Tracks, it helped him reach more listeners in his hometown: “I’m directly connecting with the Chapel Hill community, the people that support me the most, the people that I know. I’m a part of this foundation within the town of Chapel Hill.”

These are ultimately projects that serve the needs of music listeners as much as they serve the needs of artists. Stacy Schuster, of Michigan’s Kent District Library, said she hopes their collection will inspire patrons to check out more local live music. To spread the word about the new local streaming service, she’s been thinking about launching a street team—a particularly compelling outreach idea, considering the way social media promotion tends to reinforce the same types of filter bubbles that these projects can help break listeners out of.

For Schuster, it’s also an extension of her ongoing work to bring local music into the library: “Pre-pandemic, I would go to shows and purchase music directly from local musicians to add to the collection.” A couple of years ago, she proposed bringing vinyl records back to the library, and has now expanded the collection to over 1500 records, as well as circulating turntables. She partnered with a local record store to avoid buying records from Amazon.

Anna Zook, a librarian who runs Sawdust City Sounds in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, hopes that her library’s local music collection will give aspiring artists “an opportunity to see themselves” in fellow local musicians: “Hopefully this will give musicians of all ages who are working on their stuff at home, and slowly plugging away at it, and maybe think nobody ever wants to listen to this, the courage to say, maybe somebody does want to listen to my strange synth music that I've been creating by myself in my basement for the past two years.”

For some musicians, though, the incentive to be involved in these types of collections has, so far, been financial. When Zach Burba from then-Seattle-based band iji submitted music to the Seattle Public Library’s Playback collection in 2016, the band was only making an average of $50/year from streaming, and the $200 fee was helpful for scrapping together rent.

Burba has known for a long time that libraries are under-utilized resources for musicians—he once toured as a hired drummer in a band that played exclusively in libraries, and played at roughly fifty of them. And the reasons extend beyond the financial. He’s particularly interested in the library’s role as an archive for local music. Early on, Burba enjoyed submitting records to streaming services, because it felt like “contributing to a library of the future.” But that sense of optimism has since faded. “I’ve seen the impermanence of internet music, and the way things kind of tend to disappear.”

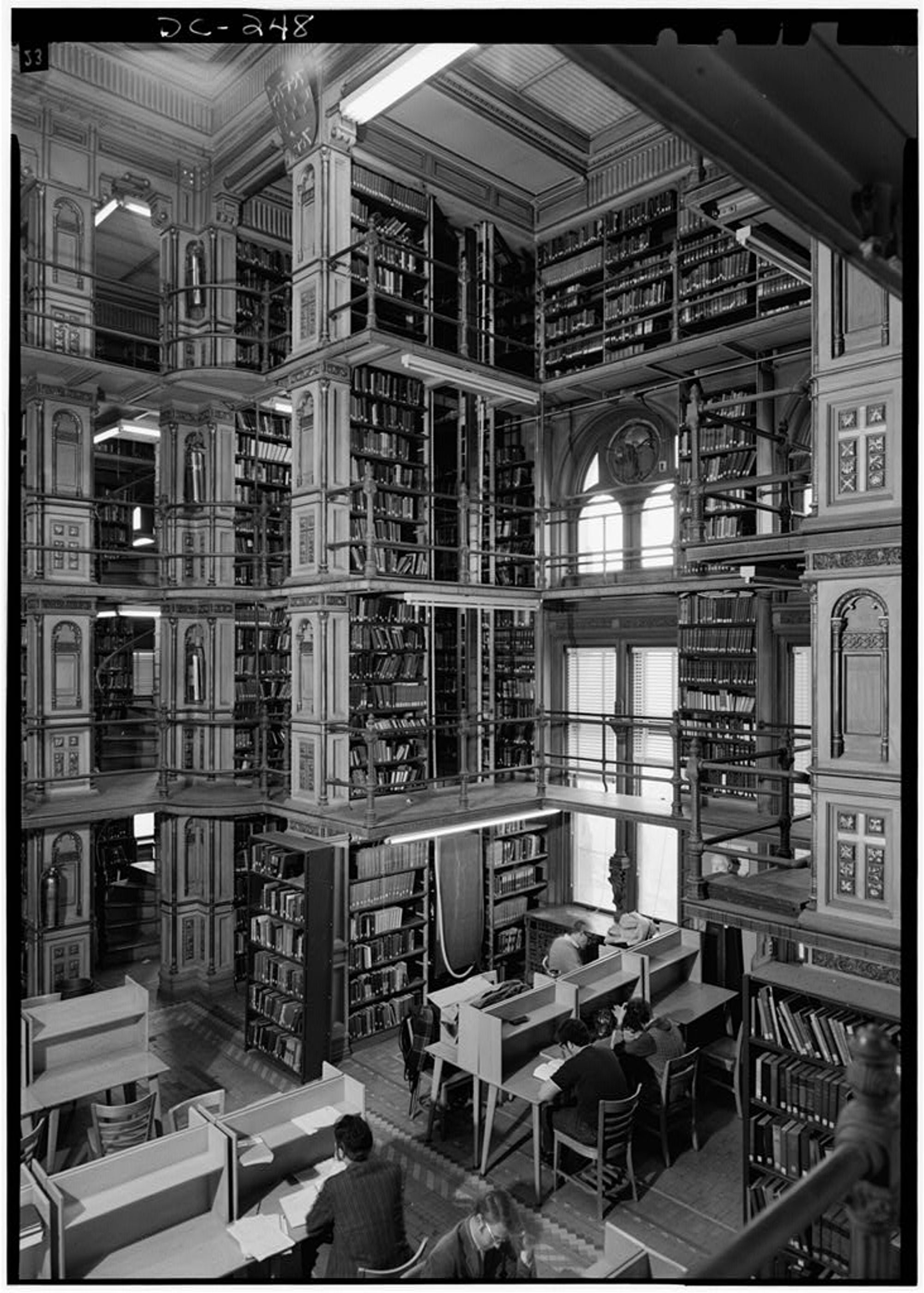

Libraries, on the other hand, have strategies for archiving for mp3s. Neiburger described the Ann Arbor District Library’s approach as straightforward: the files are backed up in multiple places, but ultimately it’s approached “the same way as excel files... backups are backups.” A bigger question for him is what access will look like in the future: what happens if devices can no longer play mp3s? The library would likely need to transcode them into whatever the popular format of the day evolves into. Archiving is another reason he feels it's important for the library to own its digital infrastructure. While private companies might be thinking about the next quarter or the next year, libraries often think about how their collections will be useful in “500 years... There's no one in the corporate world that has any incentive to think that way."

“I'm optimistic about this more than other things,” Burba added. “There's a different expectation for library music. It's a place you go to discover or to learn something, instead of to find chill beats to study to, or background music for your party. It could be a really supportive thing for music scenes. I don't think it necessarily is that yet, but I think it could be.”

Because $200 isn’t changing anyone’s lives, Rollie Pemberton says we should look to expand the other types of resources that libraries provide music communities in addition to just local streaming. “I love this idea of libraries as venues, recording studios, and even just using the public space to hang out,” he said. “Because our entire lives are just becoming overly policed, overly scrutinized… This could just be the first step to something else. The really important thing about libraries is they're free public spaces that don't ask anything of you. We have fewer and fewer spaces like that. If people become more mindful of the connection there, we might be onto something cool for the future.”

“We talk a lot about building with, not for,” said Hiser, the co-founder of MUSICat. “Partnering with communities and learning what their needs are. But on some level, people just need money. I would love to see a world in which more funding gets funneled through these projects so that license fees can be higher.”

*

Burba also happens to be a member of the Union of Musicians and Allied Workers, the group whose Chicago chapter is working on their own local streaming alternative. Andrew Clinkman, one of those UMAW Chicago members and guitarist in experimental rock group Spirits Having Fun, has been helping create and distribute the survey to Chicago musicians that will help shape the group’s approach. “It’s not clear yet exactly how aligned the public library’s vision will be with our vision for this platform,” Clinkman said. “At the same time, it's really important that it's very publicly built and publicly run. So using municipal infrastructure to do that seems like it would be the best way to go forward. I would rather lean all the way into this municipal-ized idea of how this is built and how it functions rather than leaning on independent third parties or private companies.”

As UMAW Chicago continues to research and develop its idea for a locals-only music streaming alternative, big questions loom. The members are excited by the idea of a library partnership, but also have concerns that the model could be inadvertently exclusive. Will they be able to get library cards for everyone who wants to use the service? Will Chicago musicians want library streaming? And will the library be equipped to support the music community?

As it turns out, some of these are questions that musicians have been asking for decades. In 1946, at the guidance of the American Library Association, the Social Science Research Council conducted a massive study of the American public library. As part of this two-year-long research project, the composer Otto Luening was responsible for a deep dive into music materials, with one of its goals being to figure out whether libraries were even capable of adequately supporting music, of being able to “perform specific services in the aid of music in the community.” A 2001 study of “Music Collections in American Public Libraries” published by the International Association of Music Libraries found that public libraries in 1949 faced the same basic problems as libraries of the 21st century: “lack of money to acquire materials and a shortage of qualified personnel to administer their collections.”

But the role of the library has changed since then. According to Neiburger, “in the 20th century, the library’s job was to bring the world to its community… but in the 21st century, the library brings its community to the world.” He said that these days, the library’s value is more rooted in its role as a “place where the community can be archived and kept and made available to everyone, because it doesn’t make quite as much sense for the library in every town to have its own little repository of commercially produced stuff, the same 2000 albums that every other library has… ”

A statistic that librarians like to repeat is that there are more public libraries in America than there are McDonald’s locations. That is a testament to widespread perseverance of libraries as institutions, but also to the wide array of realities that libraries exist within. Libraries are not a monolith—they have different histories, structures, resources, capacities. To interact with a public library is to interact with an institution juggling countless issues of equity and access.

Libraries also do not all conceptualize publicness in the same way. In a 2019 paper on “making space for the public in the municipal library,” two Canadian academics Lisa M Freeman and Nick Blomley argued that libraries are not only public spaces, but public property, a concept that is “complicated most immediately by competing conceptions of the ‘public’ that the library is to serve…” They noted that there is “nothing inherent or given to the ‘publicness’ of a library,” and that publicness must be actively enacted and engaged with. In their views, two substantially different concepts of public property arise, which can be thought of as “people’s property” versus “state property”: “While state property places the state as trustee of a singular public at its centre, people’s property foregrounds the state’s obligation to engage with a diverse and varied public (or publics).”

This is all to say: engaging with libraries as public spaces and local digital collections as public resources, we should make no assumptions about how a given library might conceptualize its relationship to the public. But the willingness of libraries to bring musicians into the process of governing these projects means there is an opportunity to help imagine and shape what they could be, and what the future relationships between libraries and music scenes could exist.

For those who might be interested in rallying support for the creation or increased funding of a local library streaming project, Kelly Hiser, MUSICat co-founder, had this advice: find the names of the directors and board members of your local library, and create targeted campaigns. She also recommended opening up conversations with any known allies within the library, or librarians connected to local music. “People vote in local elections in pretty low numbers, but the impact of your local school board election or city council election is profound,” she explained. “This is kind of the same thing. Those are the people who have the money at the library. And even though that money is declining right now in most places. It is all about strategies of local politics and demanding power in those places however you can.” It helps expand the conversation about equitable music futures beyond corporate accountability and into the realm of civic engagement. Hiser added: “It can be so much more impactful than just yelling at Daniel Ek on the internet.” ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast