Rafael Lozano-Hemmer's Anti-Monuments

The twinge of grief caught me by surprise, though it probably shouldn’t have. Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s installation is called A Crack in the Hourglass: An Ongoing COVID-19 Memorial, after all. But it can be easy to get so caught up in the technological and philosophical underpinnings of Lozano-Hemmer’s work that you’re unprepared for its emotional impact. A Crack in the Hourglass is on view at the Brooklyn Museum through June 26, in a small room on the fourth floor. The walls are covered, nearly floor to ceiling, with modest, 11 x 17-inch black-and-white portraits, many of them slightly fuzzy and a bit blurred, of individuals who died of COVID-19. The portraits were created by a robotic plotter, which sits at the back of the room, that deposits grains of sand onto a metal platform, line by line, to recreate images that have been submitted by the subjects’ loved ones to a website, www.acrackinthehourglass.net. Visitors to the museum can watch videos of several of those portraits being created––the edited videos run about 90 seconds, though each portrait actually takes about 30 minutes to complete. When the portrait is finished and saved digitally, viewers have a few seconds with it before the metal platform in the video tilts, the sand slides downward, and the likeness blurs and vanishes. The sudden erasure is unaccountably devastating.

Many of Lozano-Hemmer’s multimedia, participatory installations are like this––technologically sophisticated, driven by a deeply humanist intent, and often animated by the intimate physical traces of participants, like heartbeats, breath, or voice. His work is characterized by a desire to create connection across distances, both literal and figurative, whether it’s using microphones and searchlights to create “bridges of light” across the U.S.-Mexico border (Border Tuner, 2019); creating biometric portraits made up of lights that respond to the heart rates of participants (Pulse Park, 2008); establishing a collective awareness of our increasingly toxic atmosphere by inviting participants to breathe air previously breathed by other participants (Vicious Circular Breathing, 2013); or allowing individuals who’ve experienced loss during the pandemic to mourn together. The Mexican-Canadian artist, who has asthma, had COVID himself early on in the pandemic. Frightening as that may have been, he says it was the inspiration for A Crack in the Hourglass only insofar as “the sense of being connected to millions of others all over the world who had contracted the virus.” He describes the work as an “anti-monument,” a project designed to help us mourn during a time of so much loss, when all of our rituals around death and grieving have been paused. The pandemic was, and is, a global crisis, although certain populations have clearly been harder hit, and the collective nature of the work is reflected in the fact that the same grains of sand, which are continually tipped back into the plotter, are “recuperated,” as he’s put it, to make an endless number of portraits. Lozano-Hemmer originally planned to make the drawings with chia seeds, which have a special meaning for mourning rituals in Mexico, but practical considerations got in the way. “Chia seed is famously gelatinous and doesn’t flow easily,” he says.

Like Tibetan Buddhist mandalas that are painstakingly created and then ceremonially erased, the portraits in A Crack in the Hourglass illustrate, even celebrate, the idea of impermanence. The erasure of the portraits is a fundamental aspect of the piece, an acknowledgment that memory, despite our best efforts, fades. “I have always felt that the erasure of an elaborate mandala is downright shocking,” says Lozano-Hemmer. “All that beautiful work and now we have nothing. But the Buddhists will tell us the opposite, that its disappearance will help you understand, come to terms, accept.” The room at the Brooklyn Museum, which is small and quiet, with pew-like benches, has the atmosphere of a chapel. Watching the portraits emerge and vanish, over and over, also made me think of the Buddhist concept of the bardo, the liminal state between death and rebirth. We’re all in a sort of bardo at the moment, trying to come to terms with our losses, individually and as a society. “If you can’t mourn your losses,” says the artist, “you’ve lost your humanity.”

Lozano-Hemmer’s work is often crowd-sourced, and the central theme is frequently a search for connection, so I asked him where that impulse came from. “Probably something to do with my childhood,” he says. His parents owned nightclubs in Mexico City that were home to the city’s disco, drag, and salsa scenes. “They were absent all the time and for me, curiously, the place of intimacy, of expressing yourself, was always in relation to these gatherings and parties. Your worth was always in relation to others.” Laughing, he adds, “I don't say this as a positive thing.” Still, he believes that the purpose of art is to bring people together, to share an experience and ideally to be inspired to create new politics, new communities. “As a Mexican,” he adds, “it’s important that I don’t call it a collective––the worst shit has come through the idea of the ‘collective good’ in Latin America––but a connective. You are who you are but it’s always in relation to the connection you have to your surroundings, to the dynamic meshwork that makes us a community…All of these projects are about not being alone. I basically don’t want to be lonely.”

That seems unlikely, given that his studio, Antimodular Research, Inc. in Montreal, includes a team of programmers, designers, writers, musicians, and other collaborators, and that they seem to be constantly creating and producing work. At any given moment, Lozano-Hemmer’s projects can be seen in multiple venues. The Brooklyn Museum installation is perhaps the most low-key in a number of exhibitions on view recently. Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: Unstable Presence is at SFMOMA through March 6; Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: Pulse Topology closed at the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art in Kansas City on January 2; and the immersive, multi-part installation Atmospheric Memory was on view at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, in December 2021.

All of these exhibitions include intentionally impermanent, ephemeral, interactive artworks that, in the context of current debates about our public monuments and discussions about who and what should be memorialized––and how permanent those memorials should be––feel unexpectedly relevant. The artist mentions the 1986 piece Monument against Fascism, by Esther Shalev-Gerz and Jochen Gerz, a 12-meter-high metal column in Hamburg that was designed to sink into the ground over a period of seven years until it disappeared entirely from view: “The idea that to remember, you make something disappear is intensely poetic,” he says. It’s a notion that is apparently resonating for other artists and activists: a monument of Robert E. Lee that was taken down in Charlottesville, VA, over the summer is scheduled to be melted down and turned into another artwork by the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center.

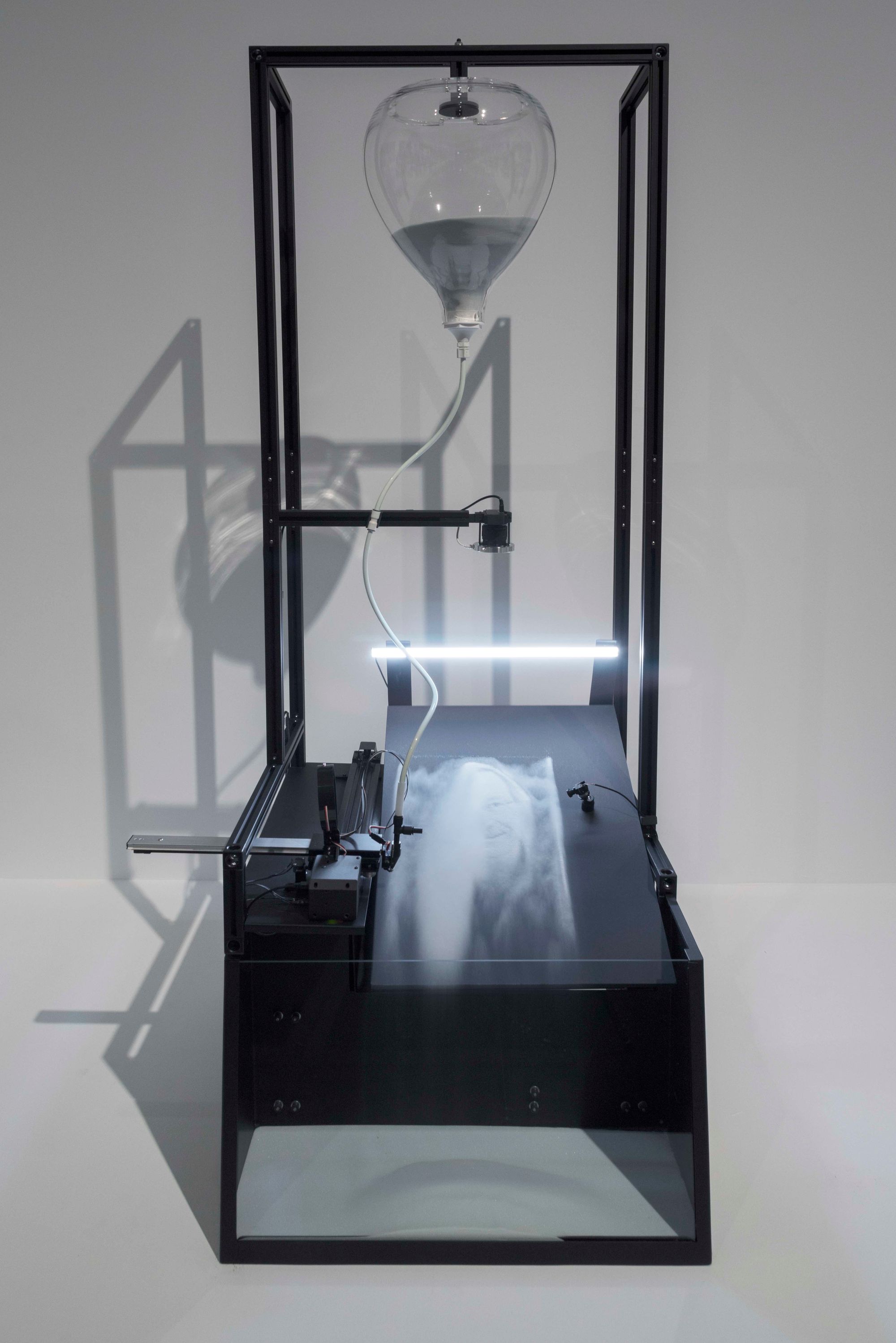

As curator Drew Sawyer put it in the Brooklyn Museum’s wall text, Lozano-Hemmer’s works “do not valorize an ideal figure, or immortalize historical narratives around race and nation, but instead assume fleeting and almost immaterial forms that exist only through public engagement.” In contrast to stone or bronze, his works are rendered in nearly intangible materials like vapor, pulse, light, voice, or––perhaps most significantly in this moment––breath. Unstable Presence was shown at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal and the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Monterrey in Mexico before coming to SFMOMA. One of the works that appeared in the first two venues but is not on view at SFMOMA––for reasons that will become obvious––is Vicious Circular Breathing. Created in 2013, the piece consists of a transparent, hermetically sealed chamber, a set of motorized bellows, and 61 brown paper bags that are attached to respiration tubes connected to the chamber. The breath of everyone who participates, by stepping into the chamber, is circulated and made tangible by the inflating and deflating of the bags, which crackle as they move. Each person who enters the chamber––after reading several signs that warn them of the possibility of asphyxiation, contagion, and panic––is breathing the air inhaled and exhaled by everyone else who preceded them into the room. Though the artist was the first person to sit in the room after the piece was created, he wouldn't go in again, observing good-humoredly, “I’m quite disgusted by it.” But pre-COVID, every time the piece was exhibited, visitors lined up to participate. The idea was to make people aware of the fact that we all breathe the same air and share the same polluted and increasingly toxic atmosphere, but clearly, the work has taken on additional meaning during the pandemic. Lozano-Hemmer’s participatory artworks, generally speaking, are about empowering audiences and providing agency, and there’s often a whimsical, playful aspect to them.

But in the case of Vicious Circular Breathing, everyone who participates makes the air in the chamber more toxic, and if you participated too much (stayed in the room too long) you could die. It’s a fairly appropriate message, says Lozano-Hemmer, if you’re trying to convey the dire state of the atmosphere. “Frankly, I think the work is more important now,” he adds. “Buckminster Fuller used to say that planetary problems need planetary solutions, and yet what we see with both COVID and climate change is a set of disjointed national responses, many of which don’t follow the science.”

Vicious Circular Breathing followed Lozano-Hemmer’s 2012 piece Last Breath, an installation designed to store and circulate the breath of a single person indefinitely––the most ephemeral memorial one could imagine. That piece also features a brown paper bag containing one person’s breath; motorized bellows, similar to an artificial respirator found in a hospital, cause the bag to inflate and deflate 10,000 times a day, the typical respiratory frequency of an adult. One version of the piece contains the breath of the Cuban singer Omara Portuondo; another contains the breath of American composer Pauline Oliveros, who died in 2016. As a “biometric portrait,” it’s almost absurdly intangible. But its focus on breath––not to mention its incorporation of a respirator-like mechanism—gives it a different, piercing relevance for contemporary audiences haunted by George Floyd’s last words as well as the role of respirators in keeping COVID patients alive. What more can we ask of a work of art, really, but that it be responsive to new interpretations, that it be flexible enough to invite different readings at different times? For Lozano-Hemmer, another measure of success might be an artwork’s ultimate obsolescence. A Crack in the Hourglass, he says, is designed to disappear: “We will be happy when this project is no longer necessary.” ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast