Jamel Shabazz on the Power of Photography to Incite Change

Jamel Shabazz has been long celebrated for his iconic portrayals of subjects who not only came of age within but also, more strikingly, helped define twentieth-century New York City with inimitable style. A native son of Red Hook, the photographer grew up in a public housing complex nestled between Bush Street and Centre Mall, during a time of seismic shifts pushed forth by the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War. At the young age of nine, he was introduced to Leonard Freed’s photo essay Black in White America (1968), which captured African Americans’ daily lives and struggles within a deeply discriminatory country. These stark, monochromatic depictions of racial disparity powerfully ignited Shabazz’s social consciousness, which would guide his image making for years to come.

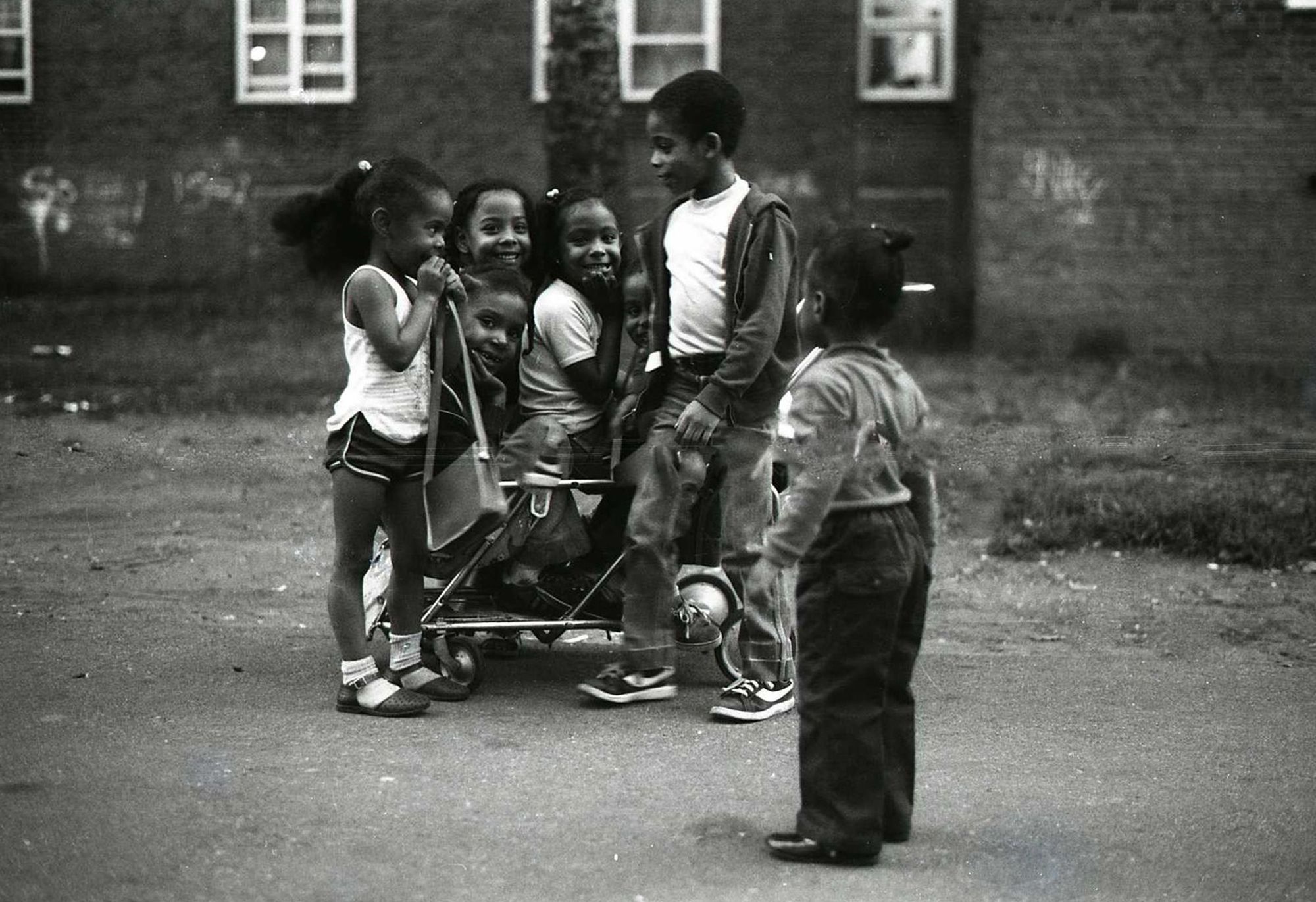

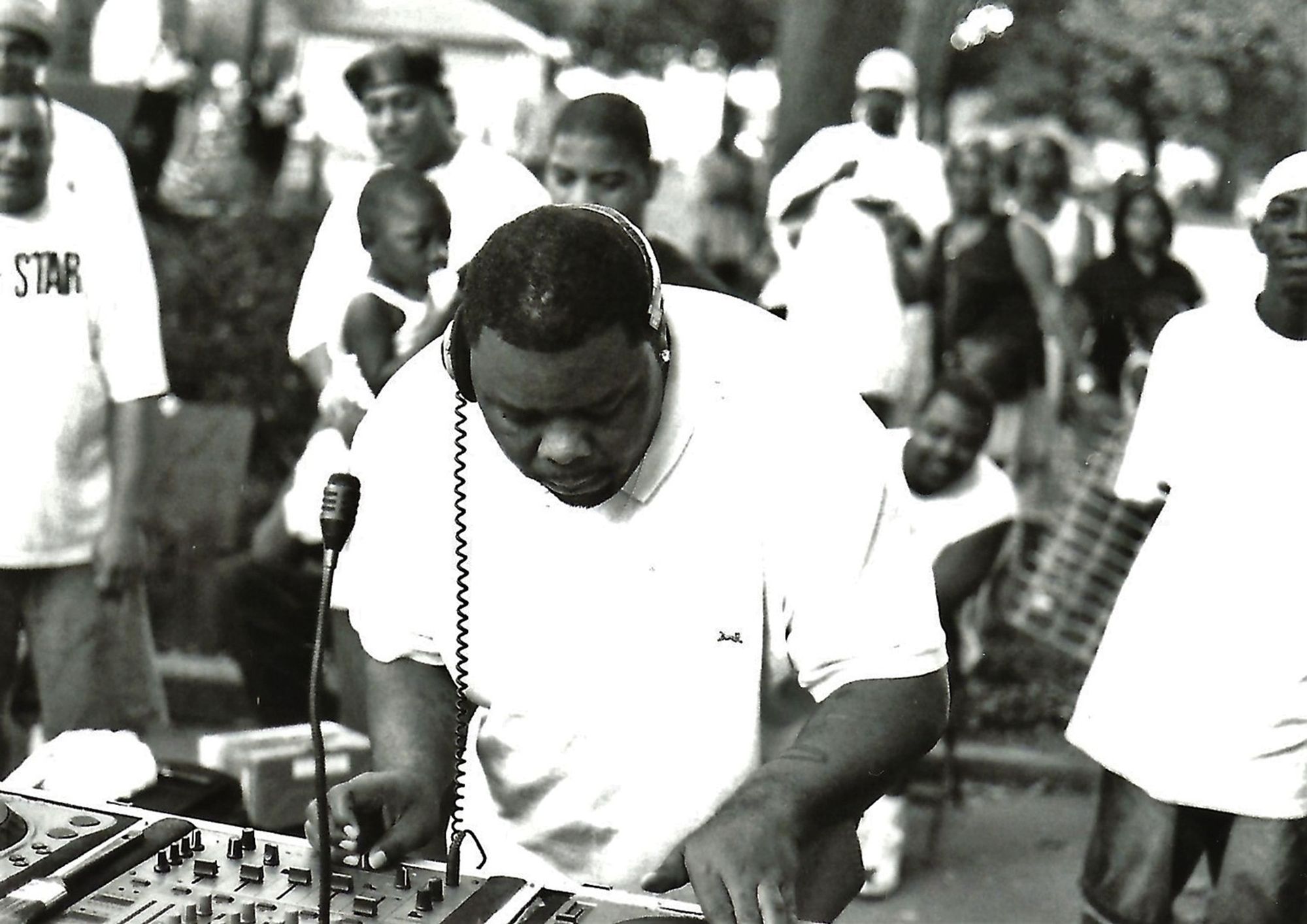

Whereas Freed acted as an investigative outsider peering in, Shabazz used photography to document the resilient individuals who populated his own universe. Created over the span of decades beginning in the 1970s, his portraits cast a dignifying light on black and brown communities in order to create a historical archive of—and, in essence, a candid love letter to—their vibrancy and creativity. In focusing his lens on the pedestrian moments and figures which surrounded him, Shabazz came to famously chronicle New York City’s hip hop, street, and youth cultures. His camera became a tool for dismantling the negative stereotypes constantly perpetuated by mass media, and a means to proclaim the beauty of those who have been systematically marginalized, as well as unduly subjected to carceral punishment and violence, within American society.

While he has achieved wide acclaim for his images of anonymous strangers and celebrated luminaries alike, Shabazz has never ceased keeping his ear to the ground. Here, he reflects on the Red Hook of his youth, the toxic resurgence of Dixiecrat ideology, and the power of photography to incite change.

You were born in 1960, and raised in Red Hook. What was the neighborhood like back then?

Let me first start off by saying that I grew up in a two-family household; my mother was a geriatric nurse, and my father was a professional photographer. During the 1960s, most fathers were military veterans, and the racial make-up in Red Hook was predominately African American from southern roots and Latino of Puerto Rican descent. We had different sections of Red Hook Houses that we called courts. On my court, there were family names like the Joneses, the Taylors, the Johnsons, the Benjamins, and the Incles. Back then, there was a mutual respect for all the neighbors. As youth, we always greeted the elders within our community as ‘Mr.’ or ‘Mrs.’ and, in return, they watched over us and corrected our behavior if we got out of line. What made Red Hook special were the beautiful Olympic-size stadium adjacent to the Gowanus Canal, a public pool, numerous parks, and the Miccio Community Center. There was also a bakery in the heart of the project called Larsens, which created an aroma of fresh cinnamon and nutmeg.

Can you recount some of your most memorable experiences during this time?

My most vivid memories came from hanging out with my cousin Sonny, who was my best friend. We were the same age and went to Catholic school together, because our parents felt that private school would provide us with a quality education. Going to Catholic school allowed me to interact with children from other cultures—the majority being of Italian and Irish descent. Interestingly enough, we never experienced any overt racism among the students; however we knew that we would not be going to our classmates’ homes after school. Sonny and I both had dogs, which—like us—had a deep bond. We spent endless hours together in that stadium, training our dogs and navigating the landscape. During that time, I remember looking out at the Gowanus Canal and seeing large cargo ships and waterways, and realizing that there was a larger world outside of my community that I would one day discover.

Another fond memory I have is playing two-hand touch football and coco-levio, during the warmer months with the kids on my block. We would play alongside Vietnam veterans who would be in their cipher playing congas and enjoying libations. Around this same time, I became very interested in the Vietnam War. I was still in my single digits, but I vividly recall young men from Red Hook going to and returning from that war. I would often see them upon their return—either from boot camp or the war itself, walking upright in their uniforms and carrying olive green duffel bags on their shoulders. Most of them had penetrating eyes that were hard to read. It would take me years to understand why.

In the summer of 1967, Red Hook lost one of its own to the war. His name was Sam White. Two distinguishable men dressed in army uniforms entered our court on a sweltering summer day, each with gloomy facial expressions. My friends and I all froze and redirected our attention from our game towards these soldiers; everything seemed to move in slow motion. As they passed by, making their way toward 100 Centre Mall, there was a short pause, and then a very loud piercing scream came from a woman which echoed throughout the entire project, causing windows to open with curious faces looking outward. Sam White had been killed in action in Vietnam at the age of just twenty years-old, and the screams we heard were that of his beloved mother. This is a period that I would never forget and has haunted me most of my life. At the same time, it inspired me to learn more about this young man. Years later, I would travel to Washington, D.C., where I would search for his name on the Vietnam Memorial.

Do you still frequent the neighborhood? I don't think that we can fairly talk about Red Hook without considering the tides of gentrification, so I wanted to ask whether you are at all concerned by the changes taking place.

The neighborhood has changed dramatically over the years, and the overwhelming majority of people that I grew up with no longer live there. However, once a year during the second weekend in August, there is an annual event called Old Timer's Day, where former and current residents come together and celebrate their connection with Red Hook. Attending these events takes me back to the Red Hook I once knew. Other than that, I seldom go back.

However, I was just recently informed about all of the changes that are now taking place—from the closure of Scott's historic barber shop that had been a permanent fixture in the community since I was a child, to the removal of all of the local playgrounds and trees. It spurred me to go investigate it for myself, and I found it to be quite depressing and devastating to see the place I once called home looking like a war zone, with all of the construction going on. Having moved away from Red Hook since the mid-1970s, I don't know much about the situation concerning gentrification but, from my conversations with former and current residents, it is a growing concern for many of them. Most feel that the new construction taking place is not intended for their benefit, but more specifically for recent implants or those who have gentrified the neighborhood.

In previous interviews and engagements, you have talked so eloquently about Leonard Freed's Black in White America, which laid bare the individual and community struggles for civil rights during the 1960s. How does that work resonate with the political and social climate of our country today—over five decades later?

That's an excellent question. Black in White America, from a very young age, introduced me to racism and the endless challenges of being black in America. From the time that I first viewed the book to this very day, I knew that there was going to be an uphill battle for freedom, justice and equality. It was quite clear to me that racism and injustice is a part of American culture, and that it will always remain that way.

Today in 2020, I personally feel that life for African Americans is far worse now than it has ever been except during slavery, despite the fact that an African American has held the presidency office for eight years. Fratricide, police brutality, mass incarceration, and disparity in health and education are still pressing issues within black communities across the country. Now with a known racist who sits at the most powerful seat in the world, we are seeing policies that mirror the Dixiecrat ideology of the 1960s that Leonard Freed spoke about in his book. Trump and his mesmerized supporters yearn for the good old days, where folks knew their place. In my opinion, the entire world has gone backwards to a very dark and dangerous time.

I think this relates to your work, which countered racist stereotypes by highlighting the beauty and strength of the black and brown communities in New York City. Was this a driving force behind your decision to become a photographer?

I always had a love for the craft, but it was not until I returned back to the United States [from military service] in the early 1980s that I seriously desired to become a full-time photographer. Newly armed with a quality camera, a working darkroom, and a father who was a professional photographer with passion about teaching me all the various aspects of image making, I realized that it was time for me to answer my calling. Some years later when the AIDS and crack epidemics surfaced, which devastated black and brown communities, I really went full force in counteracting negative stereotypes, because I realized we needed the visual medicine of positive images to sustain us.

I’m feeling that there is a critical lack of positive imagery right now—in a time where extremely disconcerting visual footage of heinous, senseless violence against people of color, primarily black people, are often made available on social media. At the same time, these images are helping foment public resistance against racism within our police force and justice system. So my last questions are: what do you think photography’s role is, within the contemporary pursuit of racial and social justice? Is there hope to be found within art?

Since its inception in the 1800s, photography has been used as a visual language to address racism and other issues of social injustice. Many conscious photographers have committed themselves to go wherever needed, even if it is in harm’s way, to capture images that can be used as vehicles to inspire change and to be on the front lines creating imagery that speaks to the time. In 1914, postcard photographs of lynchings here in America—of African Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, Asians—during the Red Hot summer were sent to friends and family. Although the photographers’ motives were questionable, the horrible images revealed the true ugliness of American racism. Photographs of attack dogs and water hoses being unleashed on those seeking freedom, justice and equality in the Jim Crow south caused an awakening and further enlightened the world to the issues of brutality and institutional racism in America. Unfiltered images taken by war photographers during Vietnam led to a global outcry which ended the war.

When we see images of the mass graves of poor and often unclaimed bodies of coronavirus victims, in caskets awaiting burial in Hart Island here in New York or some designated place in Brazil, we see the magnitude of this modern day pandemic and the lives that it has taken. More recently, it is the heart-wrenching photo of George Floyd, painfully murdered by the disgraced officer Derek Chauvin, that once again demonstrated the total disregard for human life. It has sent shock waves throughout the world, and ignited international protests. During these perilous and uncertain times, concerned photographers around the world are needed more now than ever before, to utilize their cameras as a weapon of choice to take to various front lines, capturing images that inform us of what is really going on. These are the counter narratives to the stereotypical and often misleading images that remain ever present.

Subscribe to Broadcast