"How Are You?" Care and Remembrance in the Work of Nan Goldin and Kathleen White

I.

Nan Goldin called me out of the blue one Sunday afternoon—on November 26, 2017, to be exact. It was like getting a call from Jesus Christ; or I don’t know, Robyn, being all, “Hey David, it’s Robyn, from Sweden!” It was 2pm, and my best gays and I had each had a few rounds of “brunch” drinks and I was tipsy. Maybe even a little drunk. I had a clay face mask on slowly hardening, pulling my gaping pores shut while we watched Schitt’s Creek, or maybe it was a flurry of old Madonna videos. I didn’t answer the phone thinking it was a debt collector or a robocall trying to sell me insurance for the car I don’t have. But no, it was Nan, one of the most noted, photographic chroniclers of New York City’s underground queer culture in the 80s and 90s. I had been planning an exhibition of her work at Pioneer Works for a few months at that point, and hadn't heard from her in a while. I listened to the voicemail: “Sorry this is last minute, this is Nan. Hi David. I was planning to come by [Pioneer Works] today. I don't know if you're open. At about 3:30. Is that possible? I guess you're not open today. I'm sorry I haven't been in touch. Kisses, Nan.”

I had a mini meltdown, looking like a green raccoon with “revitalizing” goo all over my face, and tried to pull myself together, to meet someone I revered in art school, in the flesh—though my friends, who aren't in the art world, were like, "Who?" Her show was going to exclusively feature big, glossy new prints of one of her recurring muses, the artist Kathleen White. Kathleen was also—in a story full of coincidences—my first neighbor in New York City when I was young, dumb, and… I was also planning a concurrent, posthumous exhibition of Kathleen’s work at Pioneer Works (she died of cancer in 2014). Capitalizing on Nan’s fame to leverage attention towards Kathleen, it was going to be a pairing of equals that also would shed some much-needed light on Kathleen’s output, which tended to be overshadowed by “that face.” Unsurprisingly, I remember well the time I first saw one of Nan’s photos of Kathleen, Kathleen at the Bowery Bar, NYC (1995), in which Kathleen, wearing a pretty, revealing blue dress, has a drink and smoke at the bar, eyes downcast as if deep in melancholy thought, the alabaster darkness of the establishment’s interior surrounding her as if closing in. It has all the pathos of that famous Edward Hopper diner painting, Nighthawks (1942), in which three people grab a bite to eat late at night, surrounded by an empty city. At the time, I thought “Holy shit, that’s Kathleen!”

In any case, the call became one of those I-remember-when moments you regale guests with at dinner parties, “that time Nan Goldin called me and I was wasted,” followed by maniacal laughter since it was so fitting, in a way, considering her work is all about dependency.

II.

It's a little difficult to pin down what Nan is perhaps most known for now, since recently photos of her shouting "Shame on Sackler," “Fund Rehab,” and throwing pill bottles into the moat around the Temple of Dendur at the Met, in the museum’s Sackler Wing, have emblazoned The New York Times. Or there’s another indelible image of her in Artforum—arguably the art world’s most high-profile periodical—lying next to the same moat, surrounded by families as part of a die-in, OxyContin bottles floating beside her like little clinical floaties. The founder and lead organizer of P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now), Nan founded the loose group to protest the Sackler family, who amassed a great fortune marketing the opioid OxyContin while simultaneously burying or ignoring the overwhelming evidence of how truly addictive the medication was.

The Sackler family almost single-handedly launched the opioid epidemic in the United States, which continues unabated, manifesting all around New York and countless towns across America. For Nan, the epidemic is personal, as she herself was addicted from 2014-2017 before kicking it after nearly overdosing on fentanyl-laced heroin. It was one of the most excruciating experiences she’s ever dealt with. “Your own skin revolts against you,” she noted to the Times in 2018. “Every part of yourself is in terrible pain.”

This was, of course, a continuing battle dating back to her youth in suburban Boston, where she chafed against the confines of her more or less “normal” upbringing. As she noted, “I wanted to get high from a really early age. I wanted to be a junkie. That's what intrigues me. Part was the Velvet Underground and the Beats and all that stuff. But, really, I wanted to be as different from my mother as I could and define myself as far as possible from the suburban life I was brought up in." Taking up heroin as a teenager, she used it briefly in art school in Boston, and then afterwards in New York City, where she moved to in 1978. There, she settled into a lower east side scene of drag queens, nightlife types, writers, and artists who shared in her spirit of rebellion and living alternatively—including its attendant drug use.

It’s this part of her life that informs the other work she’s most famous for: the slideshow and book of photographs The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1985 and 1986, respectively), which takes its name from the title of a song in Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s The Threepenny Opera (1928) (in the song a woman sings of her wayward lover: “sexual obsession has him in its thrall…a mighty genius stuck on prostitution, but when they died who paid the funeral? Whores Brecht is a very cunning reference: a playwright, poet, and revolutionary Marxist working in the 1920s, he promoted a new kind of “epic theater” that would breach the fourth wall with certain “alienation effect” tactics that made the audience self-aware of their position as audience. These included actors playing multiple roles and directly addressing viewers, placards that didactically emphasized key points of the plot, and even leaving stage lights and other behind-the-scenes objects on the all to “show that you are showing…the audience identifies with the actor as being an observer, and accordingly develops his attitude of looking

With The Ballad of Sexual Dependency this idea of looking becomes especially fraught, as we witness scenes so intensely personal—so private—that it’s almost as if a corollary fourth wall in photography between what’s public and what should be out-of-view has been irrevocably washed away. We see Nan herself smiling coyly in Nan on Brian’s lap, Nan’s birthday, New York City (1981), her arms draped around her boyfriend’s torso and her neck festooned in tasteful pearls. Expressionless, with his eyes looking at the camera and his mouth slightly agape, he looks like a deer caught in headlights, surprised by the click of the shutter. In Nan after being battered (1984), however, we see her with both eyes encircled by brown bruises, glassy with moisture from trauma. Staring at the camera defiantly, her lips are impeccably coated in deep, red lipstick, and she wears the same pearls, as if both were a badge of normalcy she refuses to It’s images like these that have led many commentators to describe her work as “confessional,” though that word seems like something of a misnomer. Confessional presupposes that some degree of guilt is involved when it’s clear a sense of almost gleeful pride runs throughout the work, even in its darkest moments.

In Getting high, New York City (1979) a man heats up heroin in a spoon, a woman’s red belt tightened around his left arm. The scene is notable for its otherwise relative normalcy: a high-heel shoe lays next to a phone, while a glass of water rests on the floor in the foreground. Greer and Robert on the bed, New York City (1982) blurrily documents a quiet moment in which artist Greer Lankton—who was born Greg Lankton and underwent sexual reassignment surgery in 1979—lies on a bed, probably very high. She was known for making papier-mâché dolls in which bodies were stretched thin and genitals were crossed between genders, implying all bodies are transitional. Next to her sits her ex, gay artist Robert Vitale, who runs his hand through his hair while he looks away. He broke up with her years before over her new gender, though they remained friends. Greer wraps her hand around her wrist, as if measuring its mass, “looking inward, full of longing, thwarted desire and her essential loneliness,” as Nan has described the moment. This is darkness of another sort, not of the graphic, drug-paraphernalia kind that’s evocative of the work of one of Nan’s most formative, stated influences, Larry Clark. His Tulsa and Teenage Lust photo series became notorious for their chronicling of youths toting guns, fucking, and doing drugs, caught in the act; in Jack and Lynn Johnson, Oklahoma City (1973) a woman grins while licking her lips, forcing a thin stream of heroin out of a hypodermic needle just before injecting it into the arm of the man before

Rather, Greer and Robert on the bed, New York City (1982) points to a kind of tone or atmosphere of existential reckoning more than any specific, graphic act—quiet, peripheral edges of an event more than the event itself. Nan’s camera chronicles fleeting moments in time, through the highs and lows, the parties and nights out, the loves fallen in and out of. “I used to think that I could never lose anyone if I photographed them enough. In fact, my pictures show me how much I’ve Robert died of AIDS in 1989, while Greer died of an overdose in 1996, seven years and fourteen years after the picture was taken,

The photograph then is “the living image of a dead thing,” as Roland Barthes would say. While I’m loathe to invoke a theorist so overly-referenced and grad school-textbook as Barthes, nonetheless his musings on a photograph’s punctum—which came out around the same time Nan was photographing these subjects—ring true here; it’s that thing that pulls your heart strings, the thing that makes Nan’s photographs so moving and yet so hard to put your finger on. The punctum is, for Barthes—writing about the picture of a man, Lewis Payne, in his jail cell waiting to be hanged—“he is going to die. I read at the same time, this will be and this has been; I observe with horror an anterior future of which death is the stake. Whether or not the subject is already dead, every photograph is this

III.

It's weird personally going through something you read about in grad school, in a canonical text of postmodernist theory—a text that’s supposed to be abstract, and somehow not real, when it’s all premised on a very real event we all have or will go through: the death of a parent. Before, I was like, “yeah, yeah, I get it.” Now, it feels urgent. As lore goes, in Camera Lucida Barthes sorts through photographs of his recently deceased mother, trying to “find” her, as if that was even possible in old photographs. Nonetheless he comes upon one, all dog-eared, which becomes the whole premise of the punctum, which literally translates as a “point,” like a prick or being struck, or cut. I found myself doing the same thing this past March, sifting through boxes of family photographs after my Dad died of cancer, feeling déjà vu from something I’d read at Columbia, in my mid-twenties.

For some people, they literally can’t look at photographs of the recently deceased. It’s too painful. For me, it became a kind of out-of-body experience, just sifting through photos the day after his corpse was wheeled out of my childhood house. I was trying to find the “best” images—him marrying my Mom; holding me up on one of those fucked-up, massive guns on a Navy destroyer; giving a thumbs up after protesting Wells Fargo’s funding of private prisons and immigrant detention facilities; mimicking the pose of a mannequin in that tacky Pierre Cardin exhibition at Brooklyn Museum, which he loved (“David, you should make an exhibition that uses lighting effects like that fashion show. So cool!”).

There’s another photograph of him I took on my phone that I’ll probably never show anyone, of his body in the hospice bed right after he died. I’m not exactly sure what compelled me to take it, except maybe I needed it to mark the event as real when at the time it seemed so the opposite. I was the only one in the room when it happened. I wasn’t even sure his last breath was his last; no one tells you these things in school. Death seems like a taboo topic, or something no one cares about because it’s so un-sexy and so un-marketable, unlike births or weddings. After he stopped moving for a while, I Googled “how to tell if someone is dead,” which is comical despite the circumstances. I really had no idea how to tell if it was the end. After the hospice nurse came by and called it, my family and I went into the other room to build a fire; he loved those. In between tending to it I would go to him in the other room, despite there being no reason to. I would touch his face and it didn’t feel like him. Nor did he look like himself. He seemed like an alien being. I wonder what Barthes would call that kind of photograph.

I still have a few of his voicemails on my iPhone, which I play now and then to hear his voice. For me, they function like photographs, as they are an index of sorts even if they’re not the literal impression of light on paper, the “thing of the past, [that] by its immediate radiations (its luminances), has really touched the surface which in turn my gaze will So too is that voicemail from Nan I have saved, which is in its own way a kind of this-has-been, even though it hasn’t happened yet.

IV.

Nan met Kathleen in 1988, most likely through their mutual friend, the photographer Shellburne Thurber, who also shot Kathleen. But Nan and Kathleen became closer when Nan was getting clean at McLean Hospital, outside Boston. Kathleen needed an apartment in the city, and Nan met some dude in her detox program who was looking for a tenant. Organizing the transaction, Nan later found out the guy was a scam artist; the landlord ran into Kathleen one day, and was like, “why are you here?” Friendship but Kathleen had to find someplace else to live. After several subsequent apartments, such as one notable storefront on Elizabeth Street, she eventually settled in with Cookie Mueller’s partner, singer and actress Sharon Niesp, in her apartment on East Sixth Street. Sharon and Cookie were also Nan’s muses (most of her friends were), and both became famous for recurring roles in John Waters movies, like Pink Flamingo. While Kathleen lived with Sharon, she started to make small, Sculptamold cars due to the sudden death of her sister at the hands of a drunk driver, in January 1999.

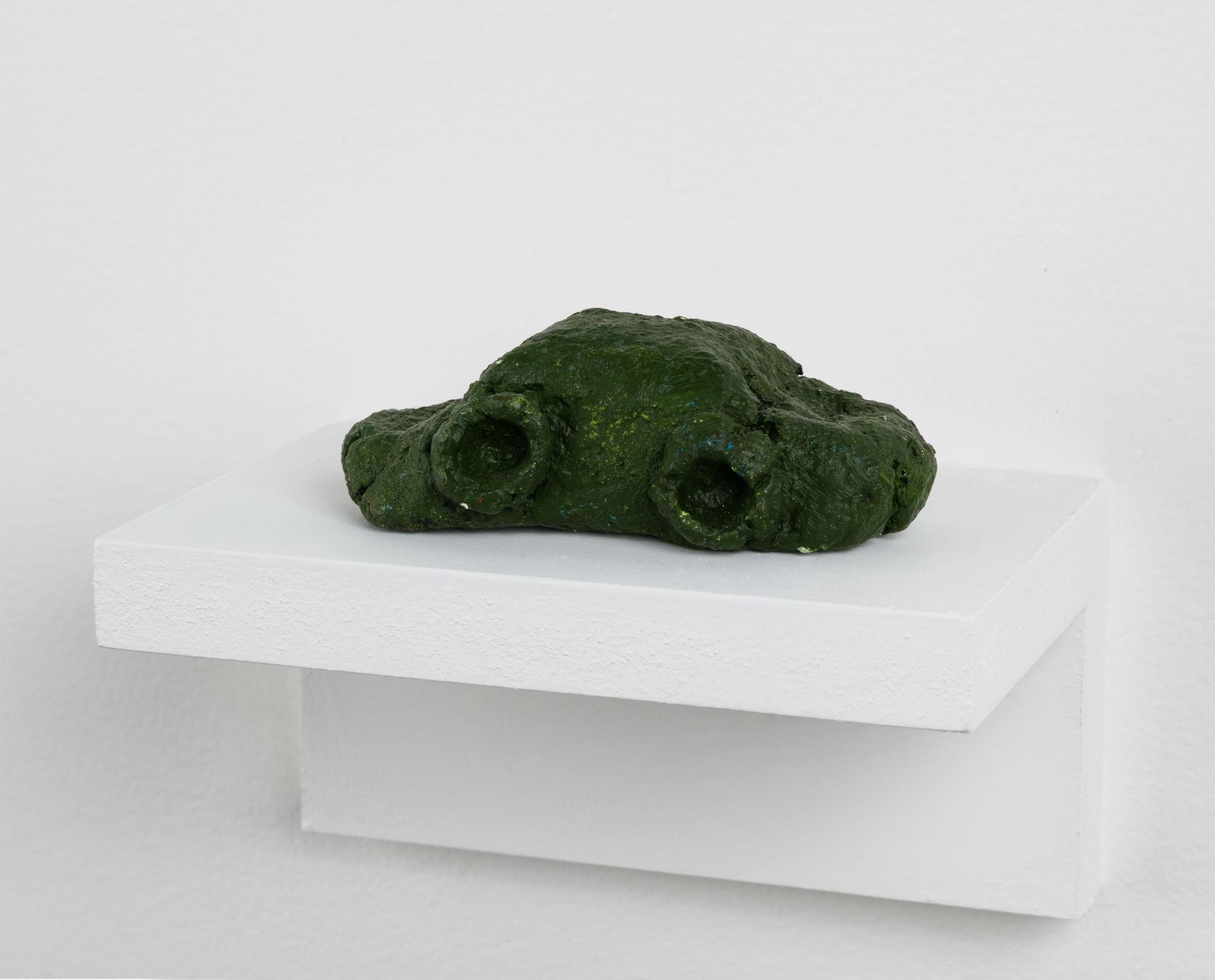

I’d say Kathleen’s work is marked by an almost elemental simplicity. Often, her canvases and sculptures are nothing more than a kind of crude mark made in paint, or an object kind of placed just-so. The cars, despite being modeled after (fairly) intricate objects, were brusquely molded by hand, and have the appearance of a blobby child’s toy, or maybe of some kind of inchoate, indestructible rock—something that could survive anything. They were literally fashioned like out of play-doh, then set by heat. She would then paint them a solid color, like green or red. In her posthumous exhibition at Martos Gallery, “Year of Firsts”—which ran concurrently with her exhibition I organized at Pioneer Works, “Spirits of Manhattan”—two of the cars were placed neatly on small, white shelves, a far cry from how I initially viewed them with her surviving partner, artist Rafael Sánchez, in her old studio in Chelsea, where there were literally heaps of them in boxes, as well as countless flat, unstretched, and unprimed canvases onto which she inscribed bright, almost chipper renderings of car after car in paint, one or two per canvas. It’s hard to overstate how gorgeous they are, and to my knowledge, these specific car works have never been shown publicly. Seen splayed on top of each other, they’re hard to focus on, but like everything else of hers in the studio, if you were to frame one or two and hang them up alone on a wall, they would command the whole space and still take your breath away. Seen on a perfectly white shelf at eye level, Car (1999-2001) looks like a sacred object.

In any case, Kathleen gave up making cars after she broke the oven in the process, precipitating an eventual move in 2001 to 151 Ludlow Street in the heart of the lower east side, aided by Sharon and Lia Gangitano, the founder of Participant Inc, whose landlord also managed the Ludlow Street address. They filled a shopping cart with Kathleen’s things and rolled it down the I moved to that same address roughly five years afterwards, when I relocated to the city from Atlanta as a wide-eyed “innocent,” settling in an apartment directly adjacent to Kathleen and Rafael’s (they lived together). It was a quintessential New York set-up, a grungy yet charming old tenement building crisscrossed by fire escapes. Its front door was covered in graffiti, and my Dad joked that when he helped me move in, he pulled up to a homeless man sleeping in front of it. In wintertime I would be jolted awake by the clanging of radiators, and I could hear pigeons cooing outside my bedroom window at all times, like a kind of calming, urban soundtrack of filth. In classic fashion my window faced a brick wall two feet in front of it; that little interstitial black hole of a space was like a wind tunnel of pigeon feathers and weird smells. I never opened it. Every few nights, mountains of rat-infested trash piled up along the narrow streets, and occasionally one of the vermin would run across my feet on the way home while wasted, at 2 A.M.. It was hopelessly romantic.

Kathleen and Rafael were also a stereotype all their own—of the seasoned, urban hippie variety. Coming from Atlanta where “urban” doesn’t even really exist, this was new to me. Rafael had a long, grey beard and looked a little bit like Father Time, while Kathleen would check the mail in a glamorous, floor-length fur coat, which I professed envy of. Once Rafael asked me what my plans were for the summer solstice, to which I jokingly asked in return if he was going to dance naked in the backyard under the full moon. He probably did. He and Kathleen made a nearly eleven-foot-high dolmen out of foamcore and painted it to resemble Stonehenge. Gazing at it while sitting in a lawn chair, contesting overdraft fees from Chase bank on the phone, I looked up and thought, who the fuck are these people, and what is that?

The “what is that” was exactly the point; Rafael was primarily known as a performance artist, and Kathleen was associated with paintings and sculptures. They wanted to meet in the middle to create something that was collaborative and defied explanation. The dolmen could be taken apart and driven to any location, where it could be rebuilt and function as a locus of performances and poetry readings, or even just a social gathering; its very contingency as an artwork only underlined the contingency of art as such. It was a Duchampian readymade that wasn’t readymade, but crafted by two people, together. Its significance went over my head at the time, but to be fair, I was twenty-four and not really keyed in yet.

Installation view of Kathleen White, "A Year of Firsts," Martos Gallery, New York, December 14, 2017 - January 28, 2018.

Courtesy of The Sánchez-White Archive and Martos Gallery.

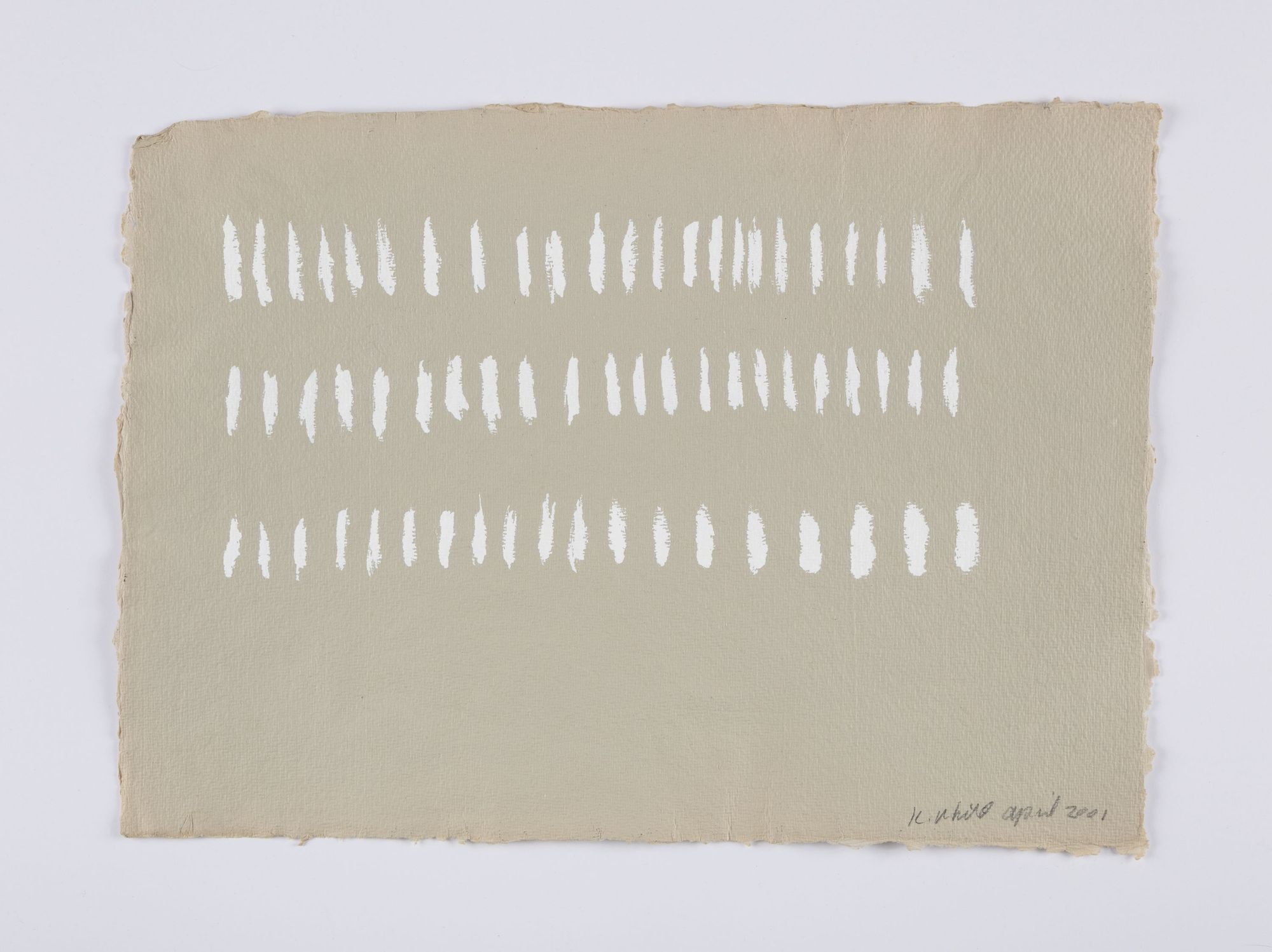

Kathleen White, "A Year of Firsts" (2001), 40 works on paper, 12 × 16 ½ inches each.

Courtesy of The Sánchez-White Archive and Martos Gallery.

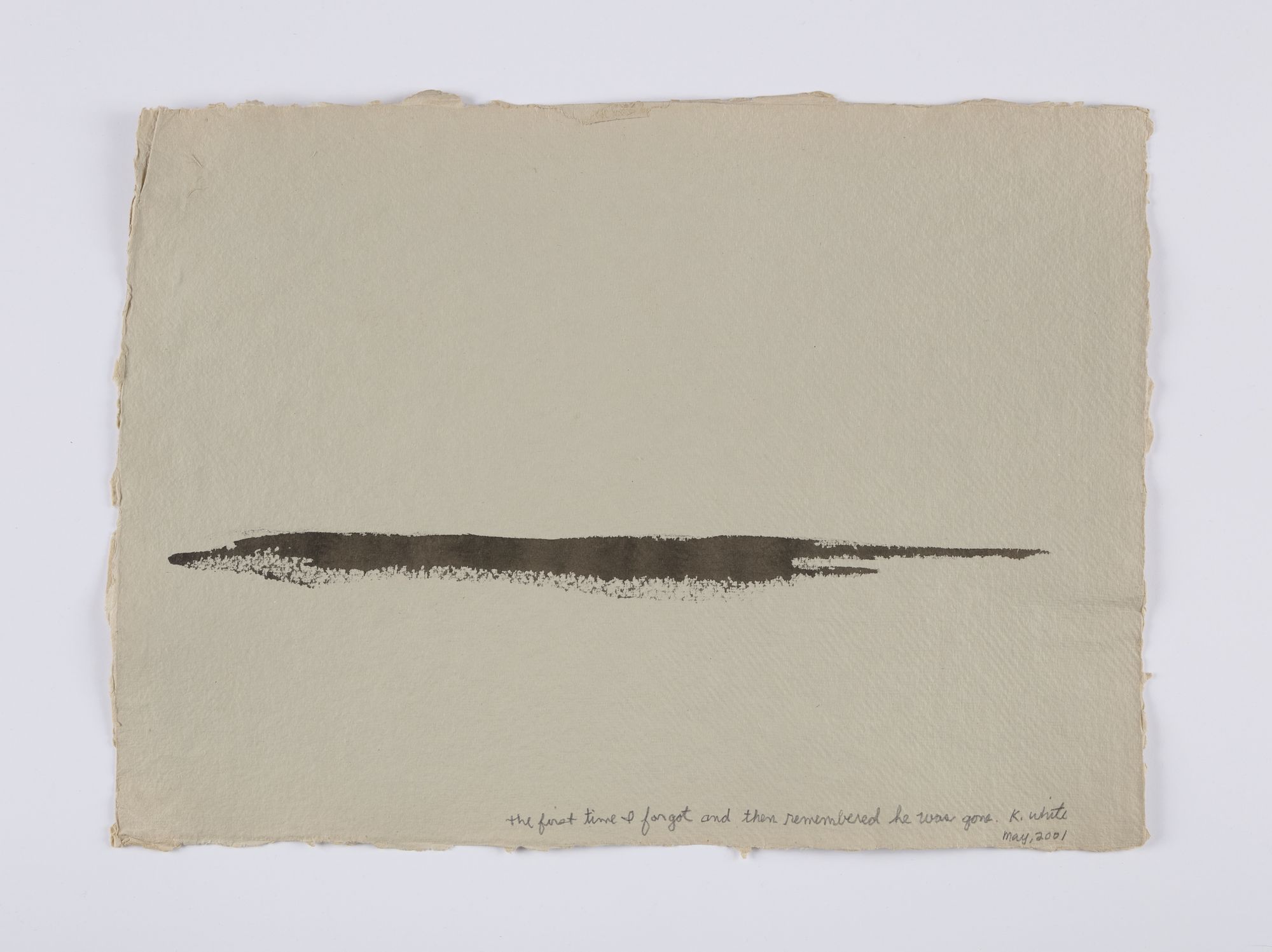

Kathleen White, "A Year of Firsts" (2001), 40 works on paper, 12 × 16 ½ inches each.

Courtesy of The Sánchez-White Archive and Martos Gallery.While she was still living with Sharon and continuing at 151 Ludlow, Kathleen also started her series of drawings A Year of Firsts (2001), instigated by her father’s death from cancer in March of that year but continued in earnest cataloging significant events during that time and from the recent past. One drawing from April, 2001, features only white tally marks—sixty-four to be exact—on the paper’s unadorned, beige background, as if she were counting down the days from some unknown event; or from May of that year in a work with a simple black brush stroke forming an inky horizon line, labeled in her handwriting, “the first time I forgot and then remembered he was gone, K. White, May, 2001.” A drawing made on September 11, 2001 consists of black darkness hovering over a swath of ocean-like blue. A Year of Firsts speaks to the almost suffocating inexorability of time passing, inevitably bearing out losses as it unfolds. These took a heavy toll on

Yet another loss—this time her twin brother Chris’s suicide in a group of works that later formed the 2014 exhibition “(A) Rake’s Progress,” curated by Rafael while Kathleen was more or less immobilized by cancer. Just after Chris's death, she started observing the seasonal, shifting colors in our building’s backyard—which together her and Rafael had turned from kind of a dump into a hardscrabble garden—as a basis for seventy-one layered, pastel monochromes created in remembrance of Chris, all arranged in a neat row around the perimeter of Momenta Art’s gallery space. Pinned to the wall at their top corners, they were left to flutter like delicate yet blank diary entries, subject to the whims of an errant breeze. They were arranged in the order they were made. In the middle of the space, a garden rake and a plumb hanging from a thread formed Rake & Plumb ( #1 ) and spoke to the precariousness of human life and the “life” of 151 Ludlow Street. A soundtrack of Kathleen typing on the typewriter, titled Sound Texts, and a video she made with Rafael of pastel-stained snow from the monochromes hanging to dry were another gesture to the space outside, a site they wanted to inhabit while it lasted; in the press materials Kathleen noted, “knowing also that the garden would soon be lost to the high rents plaguing our city…this physical exploration of color through its endless grinding, its proliferating combinations and intense contact onto the page is at once a stance of grace and defiance against all the world’s insults.”

A live performance of readings by Alex Delenois, Jim Fletcher, Alison Folland, Tavish Miller, Kate Valk, and Ben Williams—all associates and friends of Rafael and Kathleen’s—closed out the exhibition on its last night, on August 31st of that Kathleen couldn’t attend as she was in the throes of her own death and largely unconscious, though Rafael was in bed with her with the event on speakerphone; a friend at Momenta held a phone close up to the performers to establish a kind of private and rudimentary live stream. Though she wasn’t “present” in many ways, Rafael still thinks she could hear It was all ultimately a score of her.

V.

The seven prints in Nan Goldin’s exhibition of works featuring Kathleen (you guessed it, titled “Kathleen”) featured her in many guises, a conscious decision made by Rafael, Nan, and I. Most had never been printed before and were taken from a large selection of slides, numbering in the hundreds. There’s Kathleen crying in bed; Kathleen grinning mischievously in late-afternoon light; Kathleen looking like a badass bitch at Wigstock, dressed in a blue unitard in full make-up, smoking a cigarette; and Nan’s favorite, Kathleen laughing NYC (1994). Nan noted in a recent phone call, “She could be really funny. I miss her. She had a gentleness about her, but also sharp edges. She taught me to always ask people first: ‘how are you?’”

This is probably why when Nan picked up the phone she asked how I was, and how I’d been. I responded dryly, “Do you really want to know?” “Yes,” she

In another new print, Kathleen in her studio, NYC (1995) we see her in a moment of conversation or perhaps distracted, surrounded by boughs of wigs and other hair works hanging from the ceiling. Nan would curate this installation, Spirits of Manhattan (1996), in “Shy” at Artists Space in 1999, in something of a follow-up exhibition to the now storied “Witnesses: Against our Vanishing” at the same space a decade earlier, which was one of the first exhibitions to feature work exclusively about AIDS. Probably not incidentally, Spirits of Manhattan was also about AIDS, and how it decimated the drag queen community in New York City of which Kathleen was intimately involved; she made costumes for many of them, including Lady Bunny and JoJo Americo (you can see Kathleen as a background dancer in many Wigstock videos from the 90s). During that time in the lower east side, the possessions of drag queens who had succumbed to the “gay disease” were often left on the streets, their wigs heaped in piles. Spirits of Manhattan was a tribute to all of them. When Rafael and I were deciding what work of Kathleen’s to show, we decided on that installation as the exhibition’s bedrock and also as its title, as a tribute to the social scene she and Nan shared and as a way to connect the two shows.

When Rafael and I were mounting Spirits, we did a careful inventory of every hair piece, which took hours. Then we enlisted some of the drag queens featured in the work to hang the piece as they did when it originally went up at Artists Space. Rafael filmed the whole thing, as if it was a private performance of remembrance. Talking to me a few weeks ago, he said something very poignant:

"As a curator, you're actually helping things not disappear. It becomes part of the work, but ultimately that's the most beautiful part, as challenging as it is—to integrate people and make sure that conversations start to cross over between one show to the next. Part of what Kathleen was doing was curating in that sense, of caring for these things. Curating comes from the word care [from the Latin curare, “to take care of”]; she cared for these people, you know? And the tools that she had at her disposal were her art. That's how her care manifests, so that her brother is remembered; so that her father is remembered; her sister; so that the losses of AIDS are remembered. That’s what she believed

Subscribe to Broadcast