The Eternal Life of Hermeto Pascoal

Hermeto Pascoal, the visionary Brazilian composer and multi-instrumentalist, passed away on September 13, 2025. The following piece was written in 2023 to commemorate his performance at Pioneer Works. We share it now as a tribute to Hermeto's boundless spirit and lasting mark on music everywhere.

—The Editors

“When I came to earth, I came with a mission,” Hermeto Pascoal declares, looking distinctly wizard-like under his wide-brimmed hat and with his large white beard. We’re sitting in a hotel lobby in Manhattan’s Financial District, the morning after Pascoal’s sold-out show at Pioneer Works. For the 87-year-old Brazilian artist, music is not merely an artform or mode of expression, but an animating force. Throughout his six-decade-plus career, he’s consistently released music that has innovated and disrupted the world of jazz, building on Brazilian musical styles both contemporary and traditional with inventive, improvisatory gusto. He has earned a reputation even among giants; Miles Davis once remarked that he was “the most impressive musician in the world.” For him, nothing is off limits: everything he sees and hears is a creative tool. Throughout his life, this openness has led to intercontinental and unbridled works which have radically expanded the bounds of what music or an instrument can be.

“If you let it flow,” he tells me, “you’ll realize that sound is always there.” This typical, koan-like utterance turns my mind towards Pascoal’s ambitious, genre-traversing arrangements—music that incorporates numerous sounds and instruments. On “Gaio Da Roseira,” the 15-minute epic which closes his 1973 record A Música Livre De Hermeto Paschoal, spare musical passages accentuate the breadth of individual sounds. The berimbau, a single-string Afro-Brazilian percussion instrument, is struck in various manners which unveil its textural complexities; later, flutes and drums exchange solos in ways that emphasizes their evolving rhythms. This structure is a pedagogical technique, inviting listeners to understand these instruments in an isolated manner before they emerge in a larger arrangement. When the full band breaks into song, everything feels brighter, and more immense: the whistle has a percussive flair, the piano phrases are breezy, and the drum beat shuffles with the vocals in a playful warp and weft. That the song ends with conversational chatter is a reminder that making music should be a social, convivial act.

Such joyful camaraderie was palpable from the beginning of Pascoal’s Pioneer Works show—his first in New York since 2010—as well as a certain wonder, for admirers of the aged master, about the impossibly youthful exuberance of his presence. When his five bandmates arrived on stage, they huddled around microphones and began sputtering and shouting in harmonious fashion. The members gesticulated and swung their heads back, until Pascoal finally entered the stage, assuming his position at a keyboard. The band launched into a slick groove led by winding sax melodies, and their ecstatic music filled the hall.

Born in a small town called Lagoa da Canoa, Pascoal couldn’t spend much time outside in northeast Brazil’s heat due to his albinism. As we converse in the hotel, he assures me that this condition was never a hindrance. Though he began playing flute at age eight and picked up the accordion from his father three years later—quickly outpacing him—Pascoal’s musical interests precede his time with traditional instruments. When he was seven years old, he would help out at his grandfather’s blacksmithing shop. “He would ask me to throw things away, but I wouldn’t,” he recalls. “I would hide them in my room and start building stuff.” His mom eventually walked into his bedroom to find it littered with scrap metal that Pascoal had hung on a clothesline. Where his mother saw garbage and disarray, Pascoal saw an entire world of possibility. He would play with this scrap metal before learning the flute or sanfona (an eight-button accordion), but he didn’t call what he did music; he had never heard the word before. “They were just sounds, and they made sense to me.” He goes on to explain his lifelong curiosity. “I think in the same way that I did when I was seven,” he tells me. “My soul is the same, it’s just my body that’s grown up.” Be it with a symphonic orchestra, in his sextet, or solo, he approaches music intuitively but with purpose, often composing pieces in a manner where the planned and the improvised are impossible to discern.

During Pascoal’s set at Pioneer Works, he occasionally took a seat, choosing not to play anything for minutes on end. I chalked this up to the weariness of age, but he explains that he wasn’t doing it to rest. “It’s to appreciate, to see the audience, and to feel better,” he assures me. Watching him sit there, happily bobbing his head to the music, I thought about how listening necessitates a sort of concentration that can be as demanding as playing music: receiving any sound is to be in a posture of ultimate sensitivity. It’s an insight that Pascoal has long nurtured, since his rural childhood, in bustling cities. He has been based in Rio de Janeiro for decades now, but in the 1970s spent several long stints in New York. “I wanted to play my flute but the neighbors would complain,” he says. After moving his practice outdoors, people began to congregate, mesmerized by his playing. He never performed any actual songs, though. Instead, he would tune in to the sounds around him and improvise. “A bird would sing and I would reply on the flute, or a fire truck would pass and I would play with it.”

The city’s sonic density, for Pascoal, was a constant source of inspiration. “Everything is together here—there are birds singing and fish swimming in ponds, there are cars and people and horse-drawn carriages. I consider all of it nature, and I really like that it’s all part of the entire atmosphere—that’s music.” His stories of New York remind me of “Quando As Aves Se Encontram, Nasce O Som” (“When Birds Meet, Sound is Born”), from the 1992 Hermeto Pascoal e Grupo album Festa Dos Deuses. It’s a brief track that cycles through a series of warbles and chirps, the Rhodes piano and percussion intermingling with the various avians. “O Galo Do Airan” is even more audacious, prominently featuring rooster crows amid boisterous instrumentation: drums and whistles, a piano and soprano saxophone, even a berrante—an ox horn traditionally used by Brazilian shepherds.

The most astonishing bird sounds one can hear on a Pascoal recording are on “Papagaio Alegre,” the fourth track on the 1984 album Lagoa Da Canoa Município De Arapiraca. The song prominently features his pet parrot Floriano. Its coarse timbre takes on a multitude of feelings; at certain moments it sounds like rambunctious children, while at others it provides a counterpoint to other noises, some of which come from a percussion instrument made from a tape reel he calls the redongulo (a portmanteau of the Portuguese words for “round” and “triangle”).

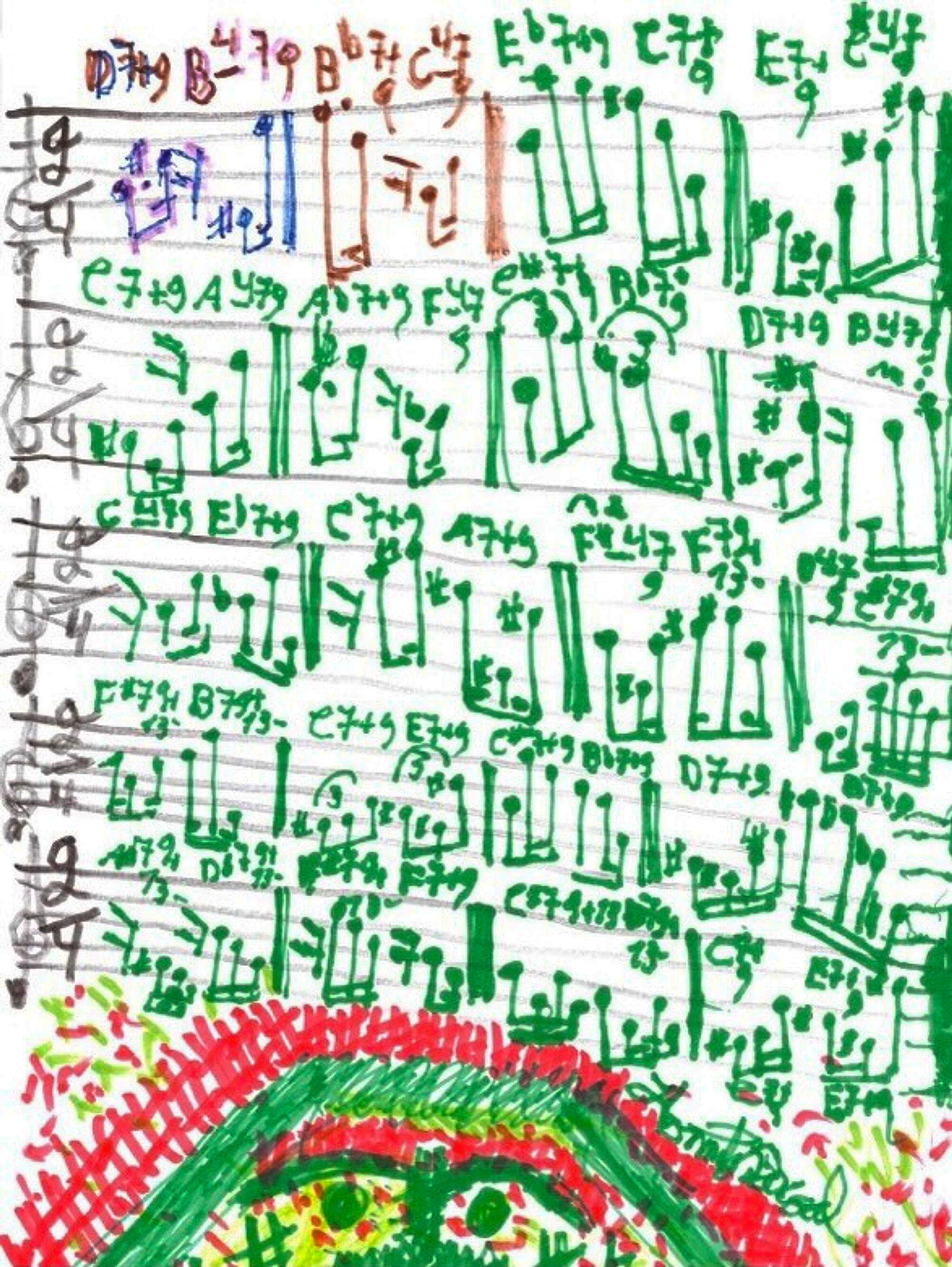

“Papagaio Alegre” is one of the most thrilling tracks in Pascoal’s discography because it showcases an approach to songwriting that rejects the way music is taught in schools. “They use a lot of theory but have it all wrong,” he laments. “Music is out in the world and you have to catch it before it flies away. Then you can write it on paper if you want to experience it again.” He thinks composers who have attended prestigious academies approach writing in the opposite direction, obsessed with using theory and putting their own creations out into the world. “There are limitations to formal reading, to formal writing and notation—they have their value, but don’t try to create nature from paper.”

The most famous of Pascoal’s fauna-featuring works is the title track from Slaves Mass, the 1977 LP that made him a name outside of Brazil. While recording the album in Los Angeles, he brought local pigs into Hollywood’s Paramount Studio to record their squealing. (The family who owned the swine came as well to ensure they’d be treated humanely.) At first, their grunting accompanies a loping guitar figure, painting the animals as contemplative but firm. A nimble bassline then energizes the piece before a six-person group chant steals the show. The pigs slot nicely into the mix as an actual instrument: their gruff grunting seamlessly blends with the freewheeling singing and laughter.

There were unfortunately no live animals at the Pioneer Works show in May, but Pascoal’s son Fabio did have a toy pig that made noise. He cycled between that, other toys, a kazoo, a whistle, a tambourine, a friction drum, and more. Like the rest of the band, he was embodying “universal music”—Pascoal’s apt term for a musical practice that’s born of regional styles and sounds from distinct worldly places, but that also transcends them. (“My mind is not geographically locatable, it’s something that goes beyond,” he tells me.) On Slaves Mass, there’s a dissonant piano track, “Just Listen,” that pulls from the Brazilian duple-meter baião rhythm, with frantic playing matched by playful shrieks. The song slots nicely beside a sweet and deceptively kaleidoscopic piece, “That Waltz,” whose cuíca—a lightweight friction drum from Brazil—could be mistaken for a bird.

I kept thinking about this phrase—“universal music”—while watching Pascoal and his group perform. Throughout the night, a circular colored light showed occasionally on a screen behind the musicians. About 30 minutes in, an orange light appeared right as an emphatic bassline was played, emanating a radiant sunrise. The next morning in his hotel, a smiling Pascoal tells me death doesn’t scare him at all. “People think about it as an end, but for me it’s just part of the journey.”

He warns against real death. “You have to be very careful with children,” he tells me, calling back to our conversation about music schools. “People try to teach them stuff that they think is right, and don’t respect who the children are.” He’s grateful to have been awarded an honorary doctorate from Juilliard, but he has a warning for those aspiring to credentials rather than hard-won knowledge. “When people graduate, they sometimes think they know stuff and hide behind their degree. That’s what dying is. When you think you know, that’s when you’ve really died.”

Pascoal and his bandmates concluded their set in the same way it started: musicians gathered together, singing and playing instruments like they were in the most intimate of settings. They walked off stage, shaking tambourines until the applause drowned everything out. Pascoal was the last to leave, melodica in hand, waving goodbye to the hundreds of people in front of him. Or maybe it was another hello, as he knew there was more music to come, not necessarily from the band, but from the trees and birds in the vicinity, the small talk after the concert, the feet scurrying toward the exit. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast