Happy Birthday, John Ashbery

Today marks the birthday of the late great poet John Ashbery and five years since he presented his book Breezeway at Pioneer Works in 2015. The night honoring Ashbery featured other prominent poets Ben Lerner, Geoffrey O'Brien, Monica De La Torre, and John Yau reading their favorites. Instead of reading his own vintage poems or even something from his fresh book of new poems, the 88 year-old Asbery told us he was going to read unpublished work, poems he had composed in the last few months. The generative expansiveness of Ashbery can't be overstated and playing to that tune, Broadcast is laying at your scrolling fingertips a smorgasbord.

BEN LERNER INTRODUCTION OF JOHN ASHBERY AT PIONEER WORKS ON DECEMBER 8, 2015

Some of my favorite words written about John Ashbery were written by John Ashbery about Gertrude Stein. Reviewing Stanzas in Meditation, in the July 1957 issue of Poetry, he wrote:

Like people, Miss Stein’s lines are comforting or annoying or brilliant or tedious. Like people, they sometimes make no sense and sometimes make perfect sense; or they stop short in the middle of a sentence and wander away, leaving us alone for awhile in the physical world, that collection of thoughts, flowers, weather, and proper names. And, just as with people, there is no real escape from them: one feels that if one were to close the book one would shortly re-encounter the Stanzas in life, under another guise.

Or from a little later in the same review:

Stanzas in Meditation gives one the feeling of time passing, of things happening, of a “plot,” though it would be difficult to say precisely what is going on. Sometimes the story has the logic of a dream... while at other times it becomes startlingly clear for a moment, as though a change in the wind had suddenly enabled us to hear a conversation that was taking place some distance away...

Or finally:

It is usually not events which interest Miss Stein, rather it is their “way of happening,” and the story of Stanzas in Meditation is a general, all-purpose model which each reader can adapt to fit his own set of particulars. The poem is a hymn to possibility; a celebration of the fact that the world exists, that things can happen.

Try swapping out Stanzas in Meditation for one of John’s titles...

If there is a better account of what it’s like to read Ashbery’s poems, it’s the poems themselves. “The best Ashbery poems,” says the narrator of my first novel, describe what it’s like to read an Ashbery poem; his poems refer to how their reference evanesces. And when you read about your reading in the time of your reading, mediacy is experienced immediately. It is as though the actual Ashbery poem were concealed from you, written on the other side of a mirrored surface, and you saw only the reflection of your reading. But by reflecting your reading, Ashbery’s poems allow you to attend to your attention, to experience your experience, thereby enabling a strange kind of presence. But it is a presence that keeps the virtual possibilities of poetry intact because the true poem remains beyond you, inscribed on the far side of the mirror. “You have it but you don’t have it. / You miss it, it misses you. / You miss each other.”

John has many styles and modes, and even as we speak there are no doubt critics chopping the opera up into rose periods and blue. The most recent books—Breezeway appeared last summer—contain poems that are at once intimate and foreign: reading these poems is like opening a time capsule when you’ve forgotten the logic of inclusion but still feel the pull of attachments. I recognize that word or turn of phrase, I associate it with a feeling, I just can’t remember exactly how it fit into my life. Or reading some of the recent poems is like eavesdropping on conversations in an alien world a lot like this one—as if a change in an intergalactic wind enabled us to overhear the telenovelas and advertisements and small talk of a sister civilization from which ours was separated at birth. Michael Clune has noted how often the recent poems include “archaic expressions of our own past” or “the sayings of imaginary worlds”—clichés from cultures we’ve forgotten or never known. And yet we recognize them as clichés, as made phrases. The effect is not to make the familiar strange, Clune says, but to make the strange familiar—as if we can sense a universal grammar underpinning the kitsch of all possible worlds. (It brings us closer.)

Among the many marvels of John Ashbery’s poetry as a whole is the way that his pronouns, particularly the I and the you, fill and empty and fill again as you read—like some sea creature or the chambers of the human heart. Sometimes you means all of you here tonight and sometimes just you, alone with your thoughts. I first caught a glimpse of myself dissolving into the second person of a John Ashbery poem in a Barnes and Noble in Topeka, Kansas, in 1994, and there is no aesthetic experience more responsible for my becoming a writer. I can’t remember the particular mirrored surface I encountered but I remember it was in the volume entitled A Wave. Let’s pretend it was the following poem, called “Introduction,” which I’ll read now by way of one.

To be a writer and write things You must have experiences you can write about. Just living won’t do. I have a theory About masterpieces, how to make them At very little expense, and they’re every Bit as good as the others. You can Use the same materials of the dream, at last. It’s a kind of game with no losers and only one Winner—you. First, pain gets Flashed back through the story and the story Comes out backwards and woof-side up. This is No one’s story! At least they think that For a time and the story is architecture Now, and then history of a diversified kind. A vacant episode during which the bricks got Repointed and browner. And it ends up Nobody’s, there is nothing for any of us Except that fretful vacillating around the central Question that brings us closer, For better and worse, for all this time.

— “Introduction,” from A Wave (1984, Viking) © 1984, 1993, 2008 Estate of John Ashbery. All rights reserved. Used by arrangement with Georges Borchardt, Inc.

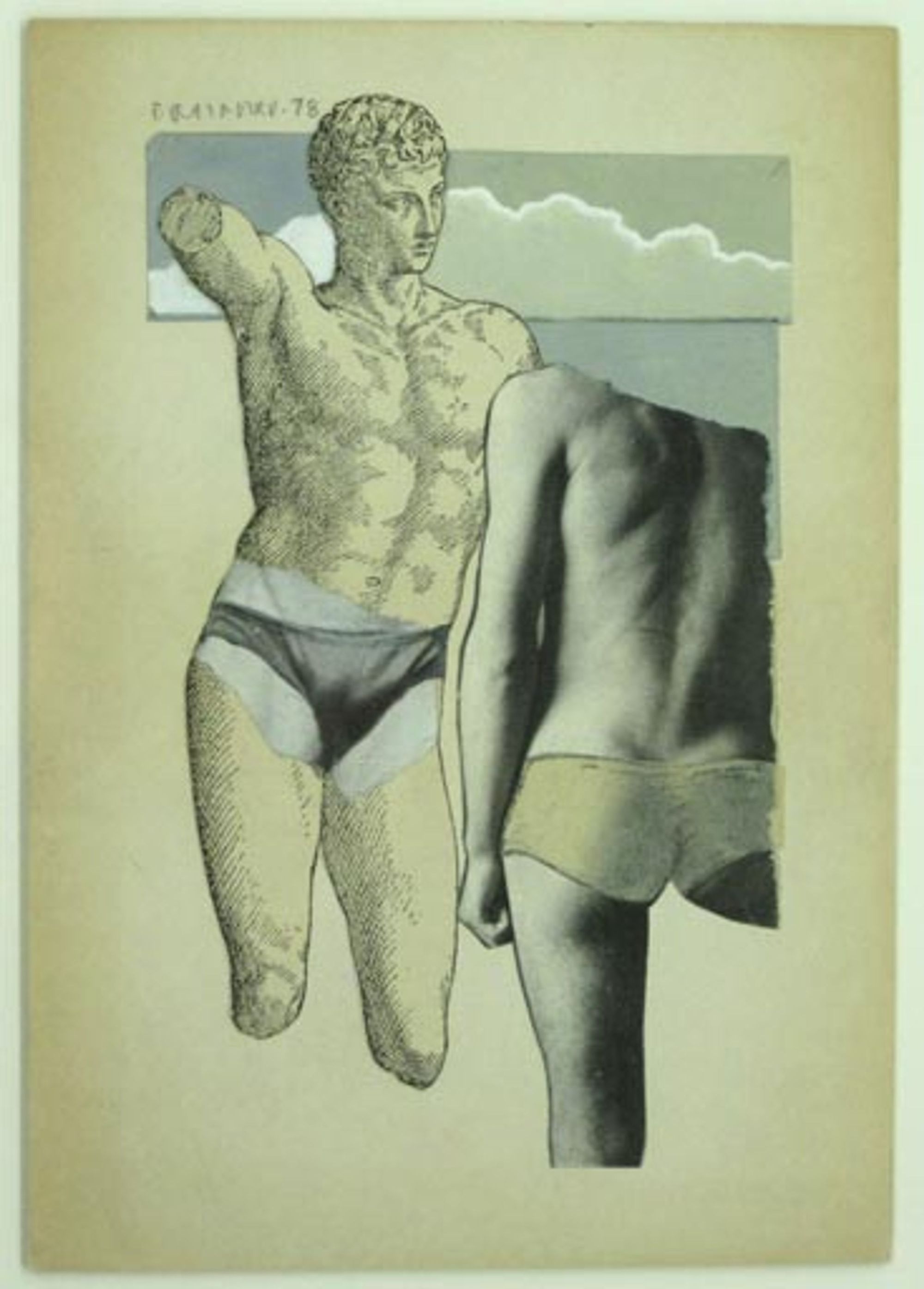

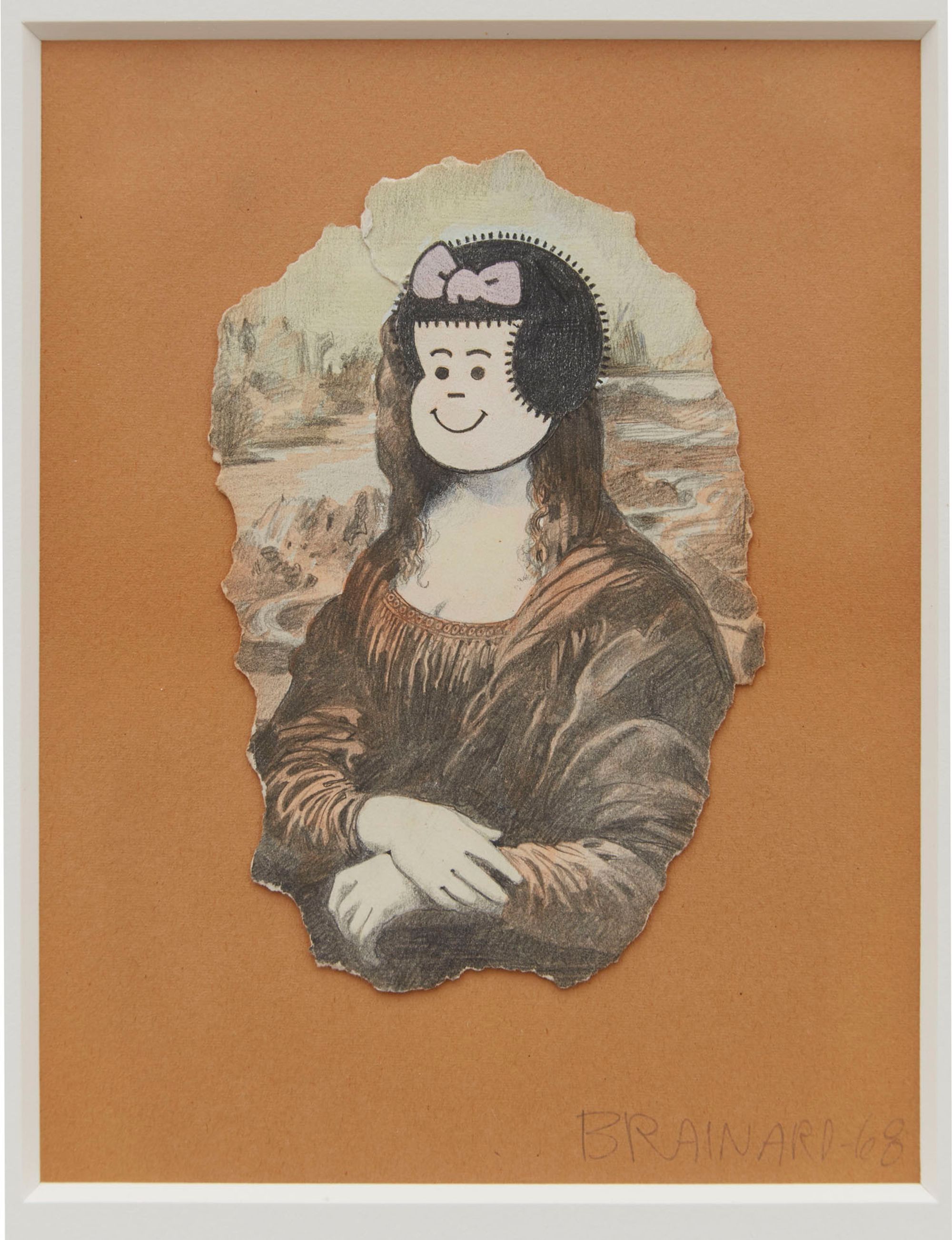

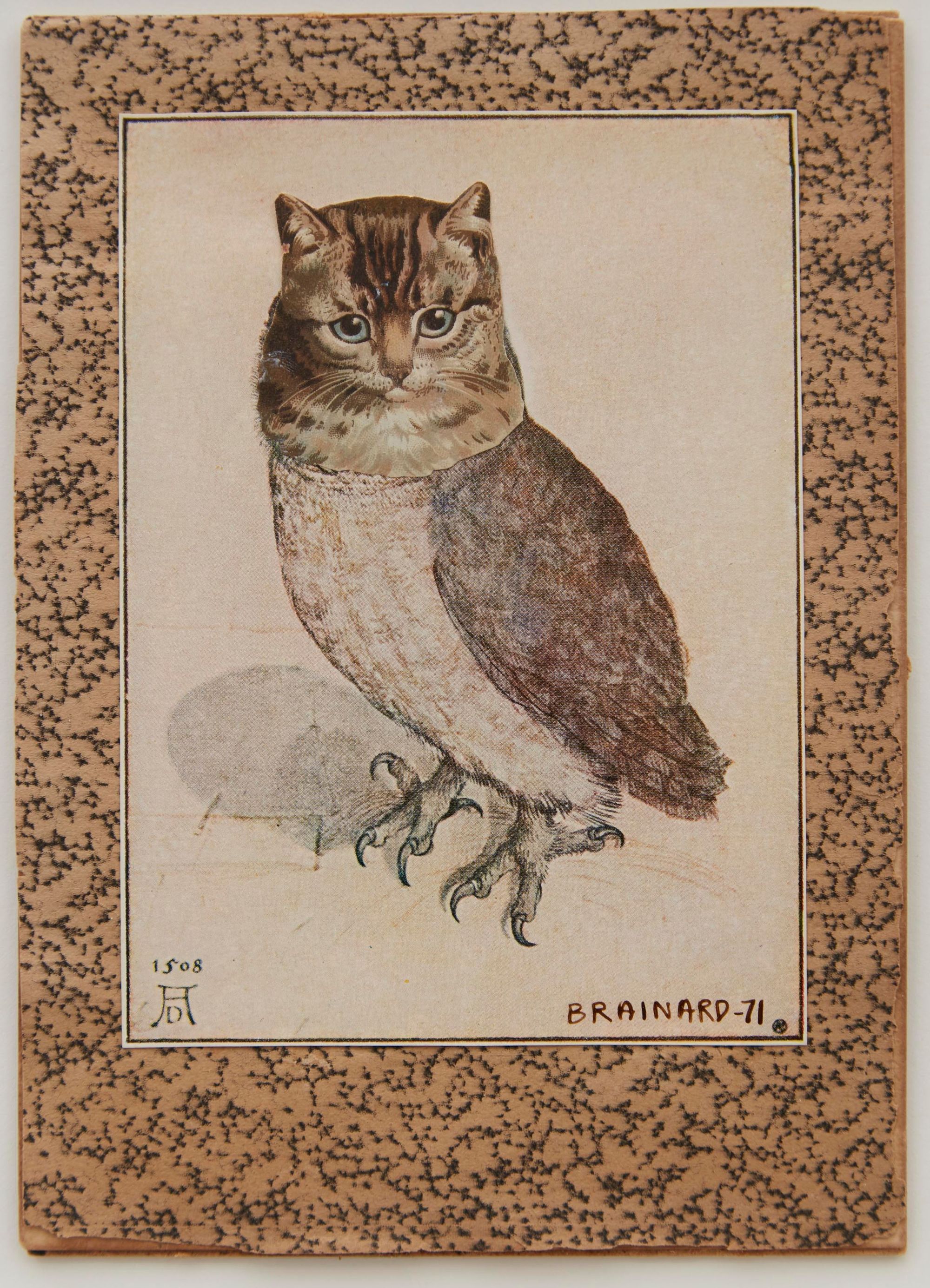

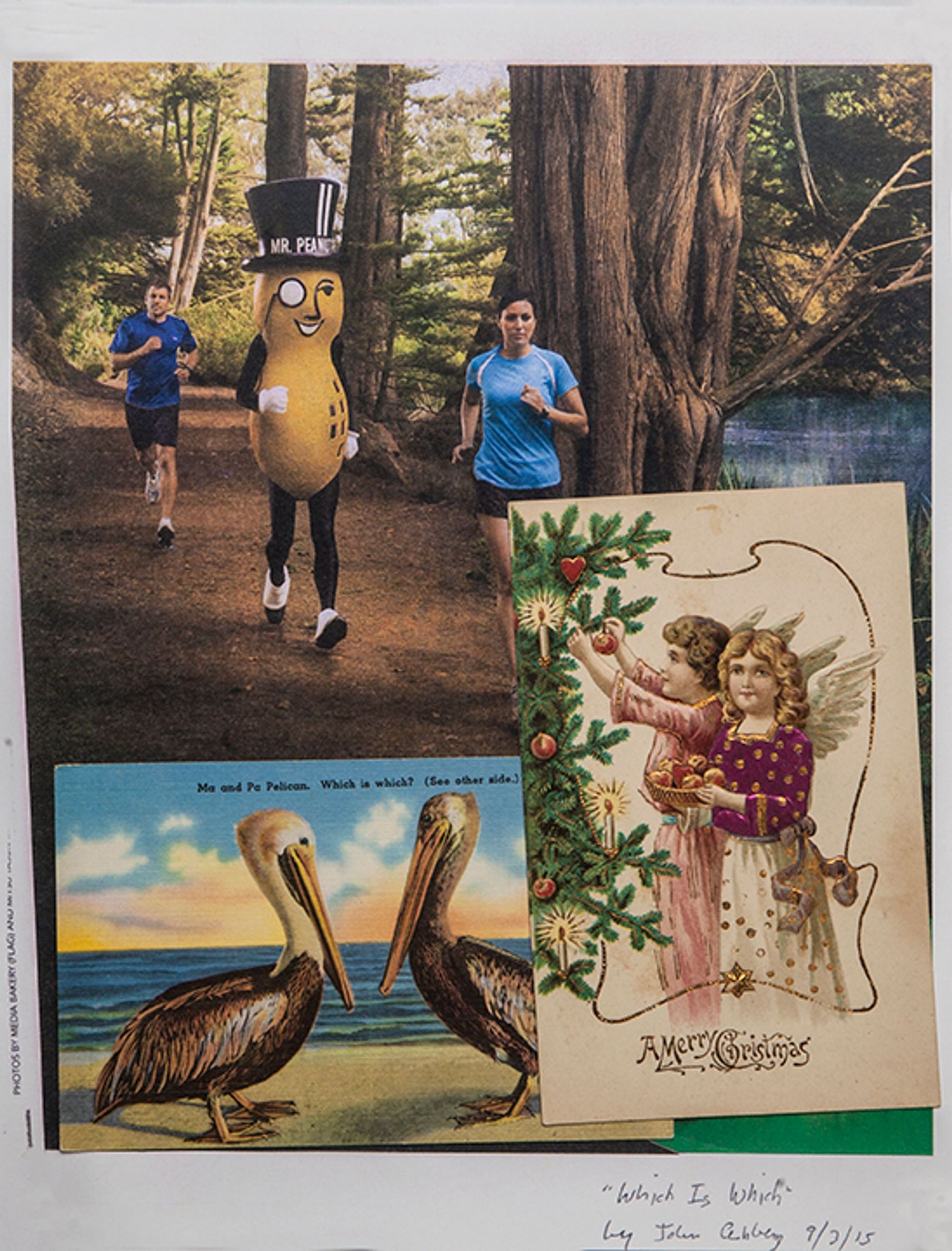

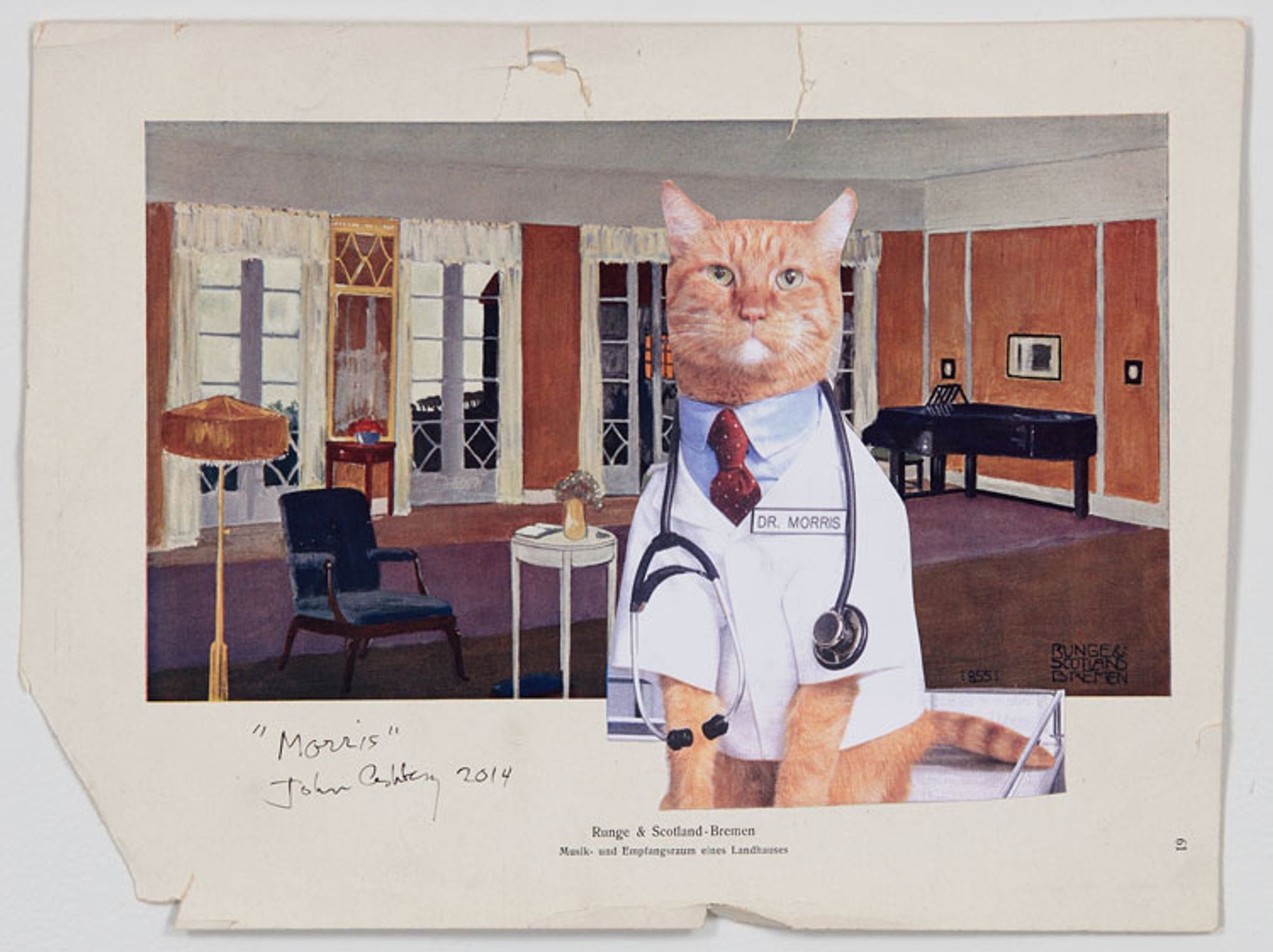

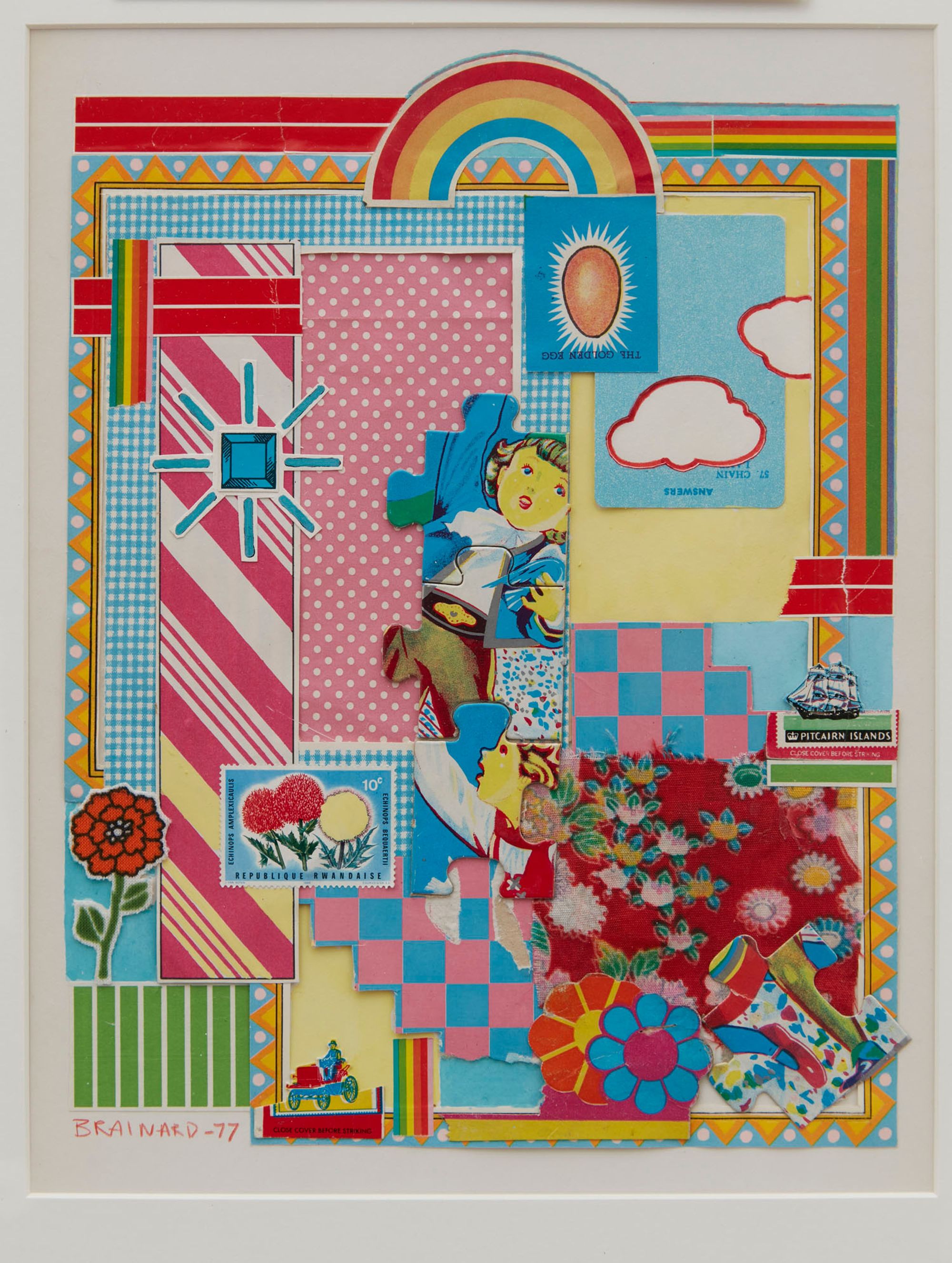

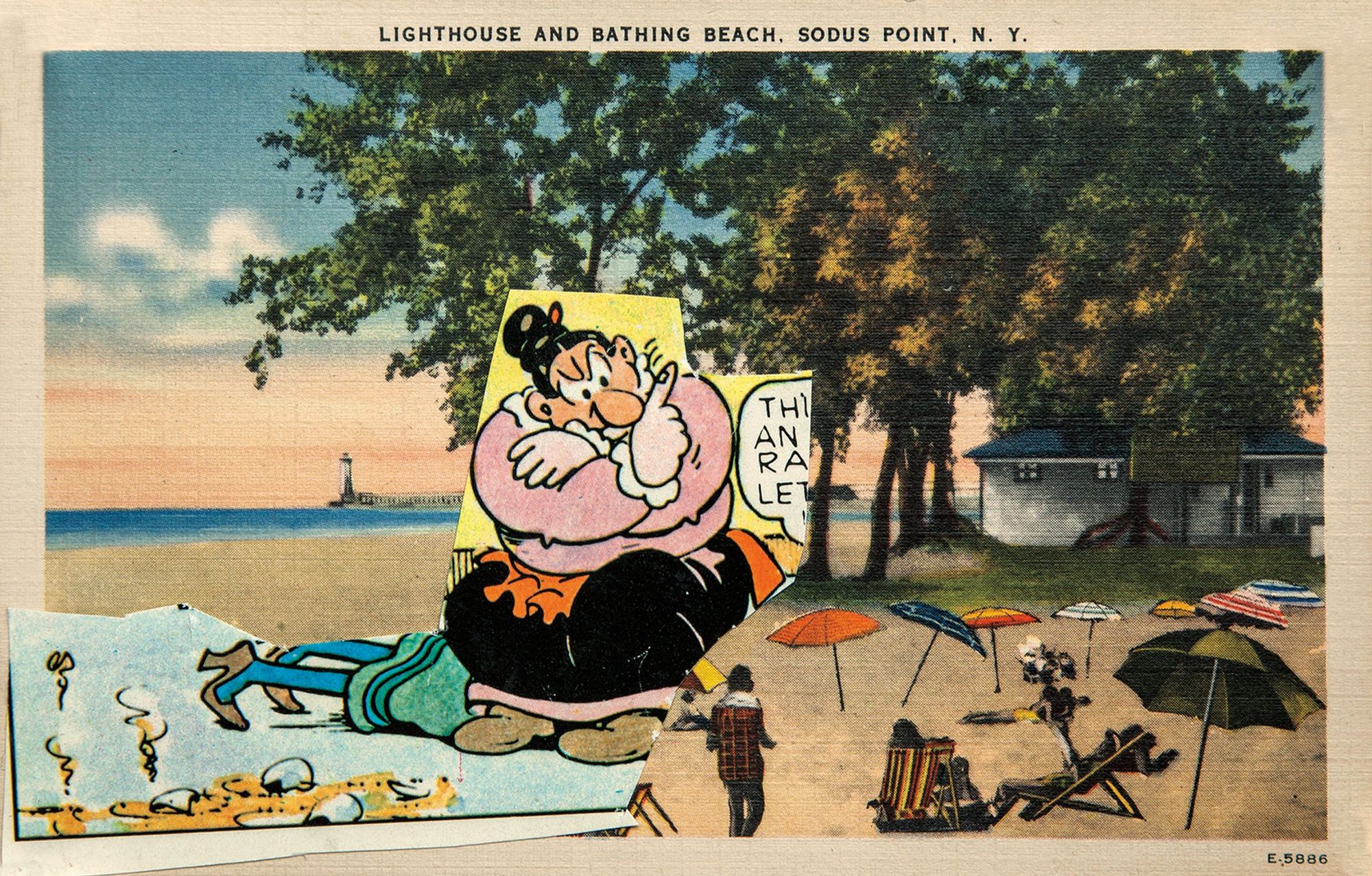

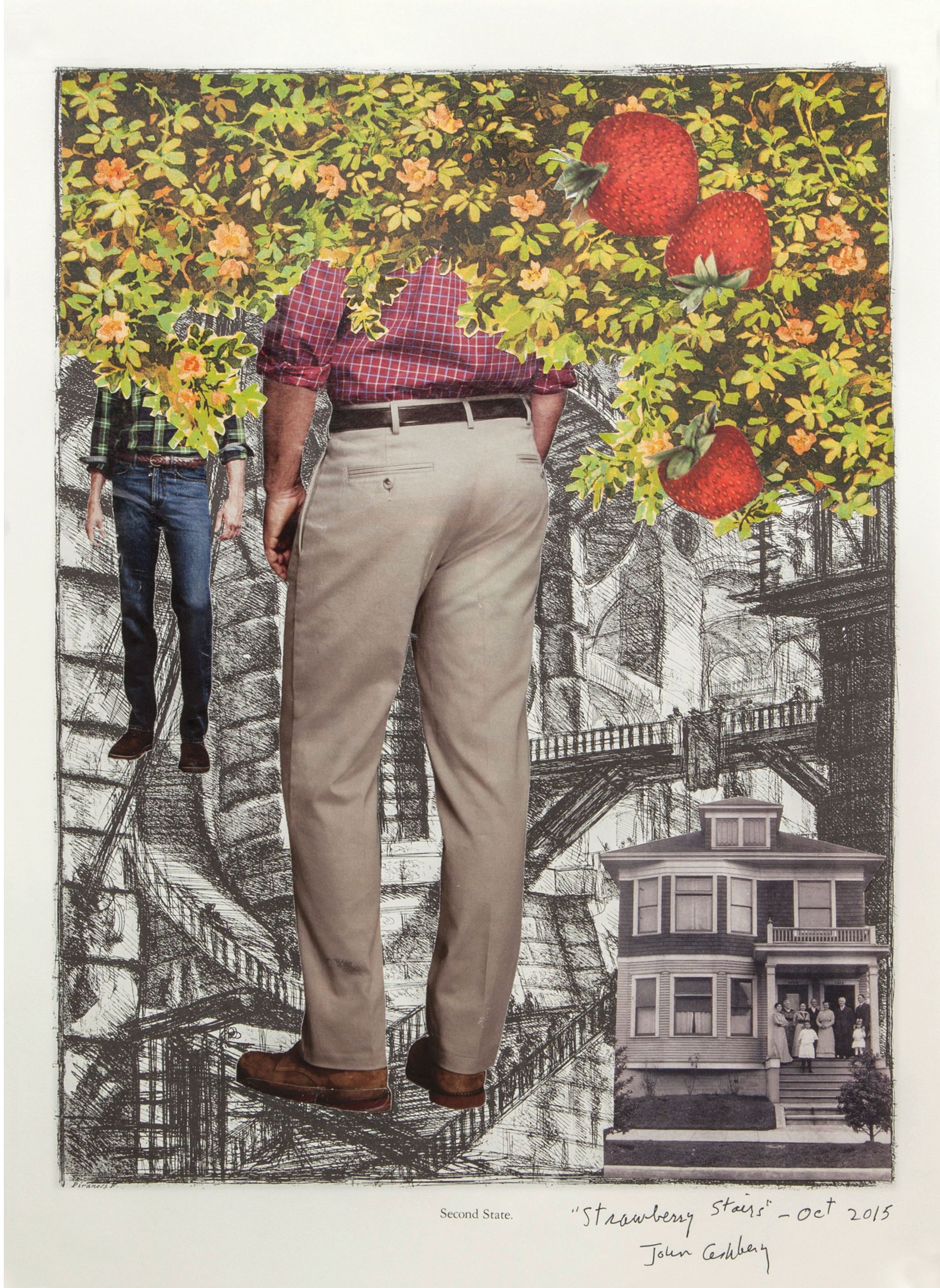

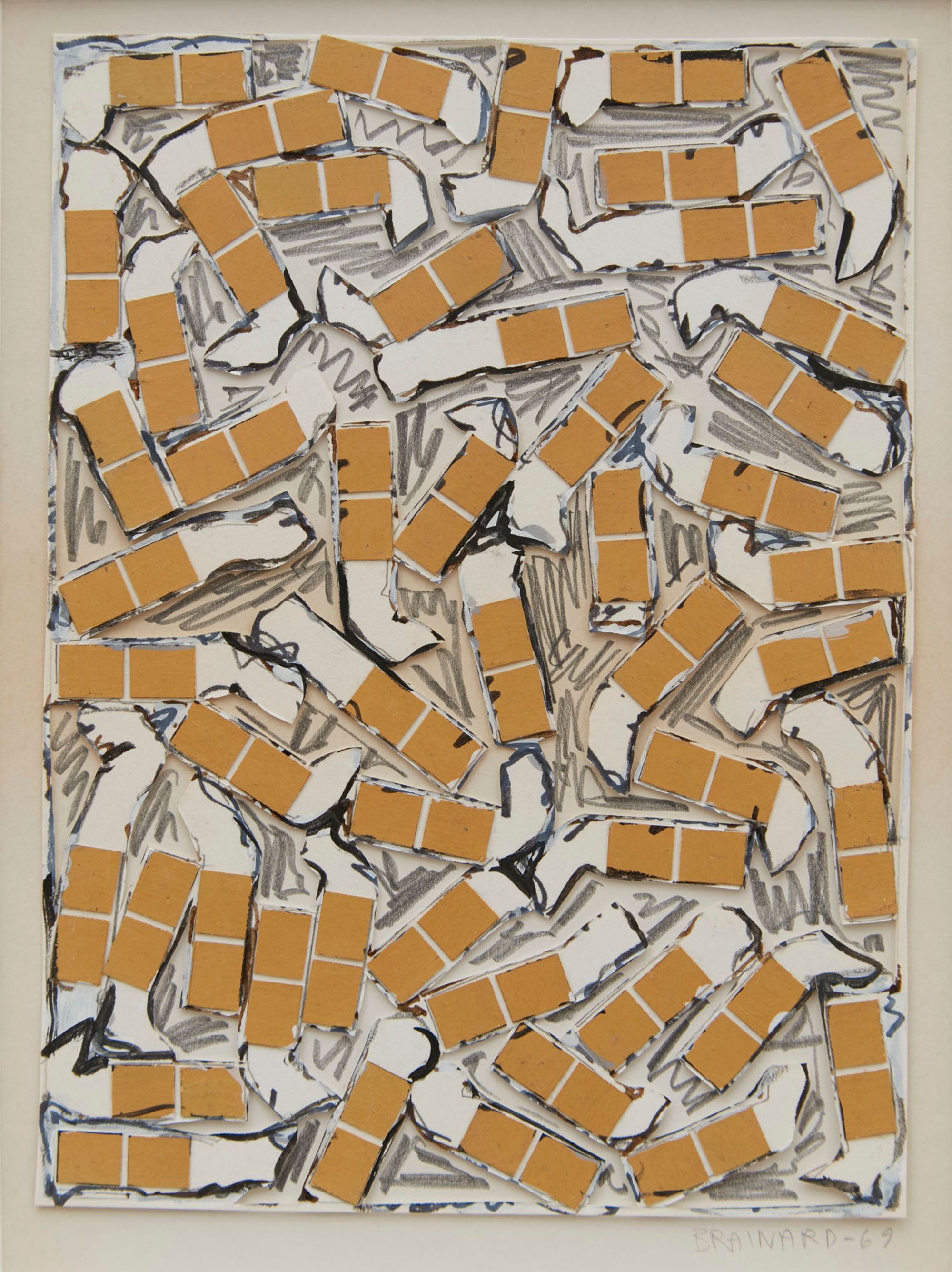

TWO MEN WITH A PEN AND A PAIR OF SCISSORS: COLLAGES AND POEMS BY JOHN ASHBERY AND JOE BRAINARD

Introduced by Jeffrey Lependorf, Executive Director of The Flow Chart Foundation

Ashbery created visual collages throughout his life. Brainard sometimes sent him materials. Sometimes they even made collages sitting together at the same table. Elements of collage enter into many of Ashbery’s poems as well, and Brainard also wrote many wonderful things, including the book-length memoir-in-the-form-of-a-poem “I Remember.” Both of their work shares—as Rona Cran tells us in her talk below, “Men with a Pair of Scissors: Joe Brainard and John Ashbery”—“an emphasis on joy, as well as an impulse to embrace the accidental.” We invite you to enjoy the exuberant sense of fun, play and frequent uncanny beauty in the works shared below. Perhaps you also will be inspired to get out a pair of scissors or a pen and make some work of your own.

We had a lot of help putting this together. Ron Padgett selected the Brainard texts to accompany the collages, and with the Ashbery collages, I selected poems that either use elements of collage or are explicitly collage poems (be they phrases from Roget’s Thesaurus or what are known as “centos,” which are poems made up entirely of lines quoted from other poems). The Tibor de Nagy Gallery—which not only represents both Ashbery and Brainard’s visual art but also served as a locus of activity for the New York School artists and poets—provided the images.

Thank you to Ron Padget, Andrew Arnot and the Tibor de Nagy Gallery, John Yau and Rizolli Electa, Max Rudin and Library of America, and Rona Cran for so kindly providing materials.

For more information about The Flow Chart Foundation and to take a virtual tour of John Ashbery's Hudson Valley home, please visit https://www.flowchartfoundation.org/.

I was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1942. No, I wasn’t. I was born in Salem, Arkansas in 1942. I always say I was born in Tulsa tho. Because we moved there when I was only a few months old. So that’s where I grew up. In Tulsa, Oklahoma. A lot has happened between then and now, but somehow, today, I just don’t feel like writing about it. It doesn’t seem all that interesting. And it’s just too complicated. What’s important is that I’m a painter and a writer. Queer. Insecure about my looks. And I need to please people too much. I work very hard. I’d give my right arm to be madly in love. (Well, my left.) And I’m optimistic about tomorrow. (Optimistic about myself, not about the world.) I’m crazy about people. Not very intelligent. But smart. I want too much. What I want most is to open up. I keep trying.

From The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard (Library of America, 2012). Reprinted by permission of the Library of America.

1.

Here is everything for everyone

you gets a delicious picnic lunch

leathers . . . sleek fit . . . perspiration

a yellow straw profile

(made of strong paper-like

substance)

Correspondence should be

what Kleenex is to the

handkerchief

luminous lovelies that help to lighten the load.

A par-

ticularly interesting effect can be seen

if a solid tube is inserted in the

window through one of the openings.

2.

Before his coming the city was

singularly devoted to the raucous,

3.

surrey to take you up into the mountains —

a marvellous idea for travelling.

buy packages of snap-in sections

of a small room the inside of which is completely covered

with leaves.

. . . tawny, tantalizing— “controls” (1952), a collage poem, was first published in The Songs We Know Best: John Ashbery’s Early Life by Karin Roffman (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2017). Copyright © 2017 Estate of John Ashbery. All rights reserved. Used by arrangement with Georges Borchardt, Inc.

They dream only of America To be lost among the thirteen million pillars of grass: "This honey is delicious Though it burns the throat." And hiding from darkness in barns They can be grownups now And the murderer's ash tray is more easily— The lake a lilac cube. He holds a key in his right hand. "Please," he asked willingly. He is thirty years old. That was before We could drive hundreds of miles At night through dandelions. When his headache grew worse we Stopped at a wire filling station. Now he cared only about signs. Was the cigar a sign? And what about the key? He went slowly into the bedroom. "I would not have broken my leg if I had not fallen Against the living room table. What is it to be back Beside the bed? There is nothing to do For our liberation, except wait in the horror of it. And I am lost without you."

— “They Dream Only of America,” a poem featuring collage elements, from The Tennis Court Oath (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1962). Copyright © 1962, 1997, 2008, 2009, 2018 Estate of John Ashbery. All rights reserved. Used by arrangement with Georges Borchardt, Inc.

Looking through a book of drawings by Holbein I realize several moments of truth. A nose (a line) so nose-like. So line-like. And then I think to myself “so what?” It’s not going to solve any of my problems. And then I realize that at the very moment of appreciation I had no problems. Then I decide that this is a pretty profound thought. And that I ought to write it down. This is what I have just done. But it doesn’t sound so profound anymore. That’s art for you.

From The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard (Library of America, 2012). Reprinted by permission of the Library of America.

Within a windowed niche of that high hall I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day. I shall rush out as I am, and walk the street The lights begin to twinkle from the rocks From camp to camp, through the foul womb of night. Come, Shepherd, and again renew the quest. And birds sit brooding in the snow. Continuous as the stars that shine, When all men were asleep the snow came flying Near where the dirty Thames does flow Through caverns measureless to man, Where thou shalt see the red-gilled fishes leap And a lovely Monkey with lollipop paws Where the remote Bermudas ride. Softly, in the dusk, a woman is singing to me: This is the cock that crowed in the morn. Who’ll be the parson? Beppo! That beard of yours becomes you not! A gentle answer did the old Man make: Farewell, ungrateful traitor, Bright as a seedsman’s packet Where the quiet-coloured end of evening smiles. Obscurest night involved the sky And brickdust Moll had screamed through half a street: “Look in my face; my name is Might-have-been, Sylvan historian, who canst thus express Every night and alle, The happy highways where I went To the hills of Chankly Bore!” Where are you going to, my pretty maid? These lovers fled away into the storm And it’s O dear, what can the matter be? For the wind is in the palm-trees, and the temple bells they say: Lay your sleeping head, my love, On the wide level of the mountain’s head, Thoughtless as monarch oaks, that shade the plain, In autumn, on the skirts of Bagley Wood. A ship is floating in the harbour now, Heavy as frost, and deep almost as life!

— “The Dong with the Luminous Nose,” a cento, from Wakefulness (New York, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1998). Copyright © 1998, 2008 Estate of John Ashbery. All rights reserved. Used by permission of Georges Borchardt.

If I’m as normal as I think I am, we’re all a bunch of weirdos.

From The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard (Library of America, 2012). Reprinted by permission of the Library of America.

RONA CRAN: MEN WITH A PAIR OF SCISSORS: JOE BRAINARD AND JOHN ASHBERY

THE COLLAGIST: JOHN ASHBERY AND JOHN YAU IN CONVERSATION.

Originally published in the Pioneer Works magazine, Intercourse, in 2016.

In 2008, Tibor de Nagy Gallery hosted Ashbery’s first ever solo show of these works, a selection of which is reprinted here. Joining him for an evening at Pioneer Works were poets Monica de la Torre, John Yau, and Ben Lerner, who honored Ashbery with a gracious introduction. In November 2016, Yau traveled to Ashbery’s home in Hudson, New York, to interview the poet about his collages and the themes and subjects behind them.

You’ve been making collages for years now. How often do you create one?

Whenever I think of one. We have a friend who works for us, doing odd jobs, who comes to help me with the cutting and gluing, which I'm not too good at any more. It depends on his hours a little bit. Usually, we work in the afternoon, and we make occasional trips to the Book Barn for source material.

So you still go to the Book Barn?

Yes.

Sneaky little devil... I didn't realize that.

Yes, I go for the old art catalogs, which they sell for like three dollars. And I’ll bring those home and cut them up.

Have you seen a lot of the art in person that you’re cutting out?

A lot of them are ones I haven’t seen. They're from catalogs like Sotheby’s or Christie’s, rather than big art books. I always feel funny about cutting up an art book, although when I start to do it, I get carried away.

So some art books, but mostly old catalogs. It seemed that you worked only on postcards, or mostly postcards, for a long time. Are the catalogs what helped you to work on a bigger scale?

When I was in college, I worked on images from art books, and other magazine illustrations. I also used a German children's book that I found at Schoenhof’s Foreign Books in Cambridge [MA].

Did you start buying books with children's images when you were in college?

I bought that one, anyway. And then another early collage that I think I still have is from Vogue, I believe. Unfortunately, a lot of my collages got thrown out when my mother sold our house in the 1960s and moved, and I wasn't there to help her, which is my punishment, I guess. I even had a very nice collage of Proust that my aunt saved and gave to me, but I don't know where it is now.

You made collages when you were in college, and then you made them in the early '50s, but you would make them only sporadically, right? Even some with James Schuyler.

Oh, I don't know if those counted, but in the '70s, we'd be invited up to Kenward Elmslie's place in Vermont, and we'd stay up all night making collages. Me, Joe Brainard, Jimmy Schuyler.

A lot of those were in my first solo show at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery. The ones that were dated in the early to mid-'70s were from Kenward's.

And Kenward was a big postcard collector, too?

Yes. I remember one of them that I made there, a postcard of some mountains in the background, and in the foreground is a man's head, wearing a hat, looking very evil.

It was when I first studied with you, which was when you were going to Kenward's place, that you told me about these postcard stories. I remember that because you said, "you can make a collage on a postcard, and then write a poem based on it." I was in your second class. Right? Because I studied with you in ’75, and it was '74 when you started…

There were some interesting people who emerged from that first class. Stuart Kaufman, Marc Cohen, Michael Malinowitz, Peter Cherches, Edward Byrne. In your class there was Debbie Gimelson.

How long did you teach there?

I taught there until 1985, and I didn't come to Bard until after my MacArthur fellowship ended in 1990. I was still at Brooklyn College at the time, and they also got money from the MacArthur Foundation, I think maybe to help them hire another faculty member. So when I prepared to leave Brooklyn College, they asked me, “well, who do we get to replace you?” So I suggested Allen Ginsberg, and everybody was very happy.

But by then had you stopped making collages. Or did you always make them regularly? Sporadic, but regularly, let's put it that way.

I don't think I did very much. It was primarily at Kenward’s. I mean, I didn't think anybody would ever be interested in them. I even kind of forgot about them myself, and then David and I were cleaning out stuff and came upon a shoebox full of my old postcards with my old collages mixed in. Somehow word about them got out, and Carrie Haddad asked if she could include a couple in a group show she was curating for her gallery in Hudson in the late 1990s, and that show sparked wider interest in them. Trevor Winkfield and Brice Brown published a selection of them in the first issue of The Sienese Shredder in 2006, which led to an invitation to have my first solo show at Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York in 2008, so I started making new ones for that show.

When did you start making the bigger collages? I remember seeing a set of collages called “Chutes and Ladders” in that show at Tibor's.

There's one in that series that's dedicated to Joe Brainard. He used to mail me things that he'd cut out, with notes to use them in my collages. I actually thought it had been lost, and was enormously relieved when I discovered that it's in a fine private collection in Connecticut. It’s one of my first big collages.

Did you cut up a Chutes and Ladders board game for the collages? I see that you have a few board games lying around as well as plenty of art magazines. If I recall, you're a bit of a pack rat.

Yes. I'd collect these vintage game boards, Chutes and Ladders, Chinese Checkers, Parcheesi, and others. David and other people would give them to me as Christmas and birthday presents. I'd have them reproduced from photographs my assistant took, and then use them as backgrounds for some of my bigger collages.

You know Michael Silverblatt collects them. He has hundreds of them. He's another pack rat. There must be a society of pack rats.

Yeah. He has an apartment just for books, doesn't he?

He has two apartments in Santa Monica, and one is just to house his books. He even took the kitchen out. And he’s still actively collecting. Are you?

Not so much. Except for the Book Barn, I don't get around much anymore. I’m mainly here just making collages for my upcoming show at Tibor de Nagy [it opened Dec. 15, 2016 – ed.]. I’ve done about 40 of them at this point.

Are you still writing or doing any translations?

Well I've been more or less in collage mode recently, since I got out of rehab. I'm expecting to go back into writing mode as soon as I can. And if I wasn’t so lazy I’d like to do more translations as well [laughs]. Maybe Max Jacob's The Dice Cup. They're really fun to do, and quite easy, though I don't think anybody has done the whole book. Maybe Paul Auster?

Paul Auster did some, and then Bill Zavatsky did that one, but it wasn't a complete.

Maybe it has to do with the availability, or unavailability, of the French rights, though I think they’re available.

I don't think the rights are that much. You know, the translations of Pierre Reverdy that I just did, I was allowed to do it for just $900, but the estate got to stipulate who could or couldn’t blurb it. So there were some strings attached. Did you meet Reverdy when you were living in Paris?

No, by that time he'd moved to Solesmes, I believe. The famous cathedral choir of Solesmes. This was in 1961—Pierre and I were then living in a tiny Parisian apartment that had both a shower and a telephone, which was unheard of. Especially the telephone, which had only then recently been made available to individual households. I mean, it was impossible to get a telephone in Paris...

Were you working on your translations of Reverdy when you were living in Paris?

I was. I translated a lot of poems for Art and Literature, which I was involved with, and also the magazine Locus Solus. I remember translating De Chirico's Hebdomeros. I didn't do the whole novel, because somebody else already had the rights to do it. But there was one passage, like the middle third of it, which I was particularly attracted to, and I translated that. I even wrote to Chirico asking for permission, and he wrote back this very ethereal little, "Oui" on the airmail paper envelope. And that was published in a sort of black market English edition by some obscure publishing company.

It's funny that he wrote in French. He once had a show in the '70s, at the Huntington Hartford Museum at Columbus Circle. I was back from Paris and went to the opening, and he was there with his wife. I think he was sort of in the hands of two American dealers, in Rome, who I had to pass through in order to be led up to the maestro. I explained who I was, and that I had already translated some of his prose poems, and would it be possible to do the rest of them. In the end, I didn't end up translating any more of them.

Why did you leave Paris?

Basically because my father had died, and I had to come back and look after my mother, who was living alone in upstate New York in a small town, on Lake Ontario, where my grandparents had owned a house where I often spent the summers. It was lovely, the little village, actually. She’d moved into that house after my grandparents died.

That's how you came to write A Nest of Ninnies, right? Driving out to see her with James Schuyler?

[laughs] We had already begun that in '52, while going out to Long Island.

Right.

The first time I ever went there, we were given a ride back by Harrison Starr, who was working on a film about Jane Freilicher called Presenting Jane. Jimmy had written a scenario for it. So Harrison and his father are in the front of the car, and Jimmy and I were bored in the back seat. And I said, "What'll we do? This is so boring." [laughs] And he said, "Why don't we write a novel?" And I said, "Well, that's good. How do we do that?" He said, "It's easy. You write the first line." [laughter] Typical of him. So I wrote the first sentence, which was, "Alice was tired." And we went on for two or three pages on that car trip. So that was in 1952. We'd get together occasionally to work on it. We found we had to be in the same room together; we couldn't do it by correspondence, meaning we weren’t able to work on it at all while I was living in France. Eventually, my editor Arthur Cohen asked me—as most editors of poets do—"Do you ever think about writing a novel?" [laughter] Yeah. I said, "Well, yes, I think I did maybe a long time ago..." So he urged me to continue working on it. Which we did. And eventually it got written and published in 1968.

Didn’t Auden give it a rave review?

Auden just liked it because there were no dirty words or sex scenes in it. In fact, I believe that the beginning of his review was, "My, what a relief to pick up a novel without dirty words and sex scenes."

Speaking of sex, and going back to your collages, they seem much more gay than you've ever been in any of your work, don't you think?

I beg your pardon? [laughter] No, I agree.

I mean, I love the one of those two guys in little tennis whites, waiting to hitchhike—I thought, "That is so gay. Which one's John, and which one's David?" [laughter]

I got that postcard at a cafe in Montpellier when I was a Fulbright student, in 1955 or something. I also had another postcard of two guys camping out with one of them crouching down and holding a baguette in a suggestive position.

They're much more gay than you've ever been in your written work. How interested were you in the visualization of gayness when you were a young man? Were you into campy stuff? Like drag queens from the 1950s. How involved with it were you?

My lips are sealed. I mean, I knew about all that, but I chose not to write about it.

But it seems all that campiness is now coming to your collages, in some way.

My play, The Heroes, is really campy. That's from the early '50s. Very early '50s. It was January, 1950 that I wrote it...

I'm trying to get at something, that you perhaps let your guard down, in a way, in the collages. Do you feel that it’s different?

I don't know. It just sort of bubbled up, from down below. [laughs]

But there's also a lot from your childhood in these collages, too. I mean, you feel it with the Krazy Kat cartoon, and some of the other cartoon references. Are some of these collages autobiographical?

Yeah, more or less. Like comic strips of my life, aside from Krazy Kat.

In that regard, there’s also this sense of innocence. That these images never descend into parody.

You're absolutely right.

I remember once we were watching some movie, it was some crime movie. We were in your apartment on 22nd Street, it was a black and white movie, and you said, "That's actually what it was like back then." And I remember thinking, "What is he talking about? This is a weird New York City movie...?" And you just up and said "It was all in black and white." [laughter]

Well, when I was growing up, we lived in the country, where it was difficult to go out and see movies and I always had this sort of feeling that I was being deprived. And no matter how many I saw, I felt this hunger for films. And it's probably still with me.

When I was looking at your collages, with their near and far perspectives, I thought, "Oh, that comes from seeing movies in the '50s, where they kind of jam different depths together." In Cinemascope, and Alfred Hitchcock was able to do it, like in Rear Window, when the camera goes up and shows you the whole backdrop. It is a fake backdrop, but it's all constructed, and you just accept its artificiality. And I thought that this notion of the artificial could be real.

Well actually, de Chirico once wrote that a faked scene in a movie is much more real than the real thing would've been.

Subscribe to Broadcast