On Loneliness

For the past year, I’ve spent most of my working hours conducting psychotherapy with students at a large public university. Over and over I’ve heard a similar story: people are very lonely. One first-year student, Melanie, struck me as charismatic and warm, yet she reported not having a single friend. When I observed that she seemed pretty comfortable talking to me, a complete stranger, she replied that being one-on-one was fine for her; it was groups that were aversive, especially since the pandemic. Week to week, I was the only person she had substantial interactions with.

In May of 2023, the U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy held a press conference and dropped an 80-page PDF affirming my armchair sociology: “loneliness and isolation represent profound threats to our health and well-being.” He attempted to make the threat real by linking it to heart disease. He also made various sympathetic policy recommendations, like funding public infrastructure and paid family leave so that people could spend more time together, or “regulating tech”—all of which, though earnest and well-meaning, leaves a kind of graduation-speech residue: it’s the strangeness of talking publicly about well-being in a country that is failing, wholesale, to support nearly anyone in being well.

Two decades before COVID-19 and a decade before smartphones, political scientist Robert Putnam traced how participation in structured social groups—whether civic, political, or otherwise—was diminishing in a country where, as he put it in his book, more people were Bowling Alone. Aloneness, it seems, has been on the rise throughout my lifetime. In trying to metabolize these sociological claims and to see if I could detect traces of this epidemic in my own life, I began to ask political and emotional questions. Each question led to another, as I recast my gaze on the world, looking for loneliness.

*

In apocalypse capitalism—can I call it that?—being alone is part of a luxury aesthetic. The ultra-rich have houses on top of buildings and hills that look out over everything below. This has always been true; is it more true now? In the U.S. especially, public spaces are déclassé. Even in spaces you pay to enter, there is often a more expensive area that’s less densely populated; think of nightclubs, airplanes, sporting events. This spatial sense of class correlates to the idea that money frees you from the inconvenience of other people. The mega-rich need not negotiate with roommates or bosses they dislike, or even have neighbors if they don’t want to. Everyone else—those of us with material constraints to negotiate—also negotiate the constraint of interdependence, of having to coexist with others.

Until recently, the fanciest mental health treatment settings in the U.S. were well-staffed hospitals, where patients received skilled care in pleasant environments. Now, the most expensive inpatient care you can buy has as its primary feature an “ultra private” setting. In treatment at “Privé Swiss,” you hang out in your luxury private cottage, with your luxury private chef and therapist and masseuse. You are not confronted with the ickiness or inconvenience of anyone who is not paid to help you, all relations reduced to the clarity of transaction. In addition to having a brand name that sounds like a sinister sex toy company, Privé Swiss demonstrates something that may be truer now than it was 20 years ago, when Robert Putnam observed that people were no longer bowling in leagues—namely, that we associate the ability to be completely alone with power, control, and elegance.

In cruel contrast, forced isolation is also a weapon. The ACLU reports that 80 thousand people are held in solitary confinement each day in this country. “Solitary” is widely understood by those who study mental health and civil rights—as well as by those who survive it—to be a form of torture, because the psychological consequences of complete aloneness cause severe traumatic stress, neurologically similar to the effects of extreme physical harm. Despite this, administrators of jails and prisons rely on solitary confinement as a tool to separate incarcerated people from one another and to mete out punishment in an already brutal setting.

The psychological horror of solitary reveals something about isolation as a condition. In our societal fantasy of the most unlivable places, people are forced into an indistinguishable mass, unable to be separate from others, whether in prisons, detention centers, refugee camps, or shelters for unhoused people. We imagine collectives and camps as sites of degradation, when the reality of such spaces is often that the worst punishment is removal from the group.

Of course, taking away someone’s individuality and autonomy is a form of violence, whether in an abusive romantic dyad, a parent-child relationship, or a state-sanctioned site of confinement. But the continuum—with incarceration’s forced togetherness on one end, and controlled luxury isolation on the other—is connected to our distorted value system in the U.S., where our erotic fixation on individualism and our anxiety about crowds and anonymity leads us to strange ideas, like that one could recover from mental illness by being almost completely alone. Perhaps ironically, solitary is the end-of-the-line nadir of sustained state violence, in a world where our greatest fantasies of power, freedom, and autonomy are conflated with isolation.

Fantasies of solitude’s safety are especially potent in the century of the mass shooting. The lonely isolation of angry men boils over into random acts of public violence, strengthening an already potent mythology around the necessity of policing and incarceration. We come to accept that public events, parks, schools, and subway platforms are dangerous places. We then buy and sell goods small and large, from Amazon-branded home security devices to real estate developments in places with “less crime”—and of course, more firearms—offering alleged protection, once again, from others.

*

I lived in New York City on and off for a decade. Recently, and with some ambivalence, I decamped for a smaller city several hours north. I feared for my extroverted tendencies, which in the city often meant cascading hangs, dates, and dinners, one social event leading to the next. I also suspected there was an out-of-balance quality to my socializing, a compulsiveness that I was curious to counter. Upstate, I live in a larger space than ever before, completely alone. The first few months, I eased into quiet, visiting friends in other small towns and frequently returning to the city. As I became accustomed to spending time alone, I became more comfortable being by myself. I learned to crave the alone time that I had previously avoided.

As I began to research loneliness, I wondered if I was lonely, and what that meant to me. How I’d once socialized in the city started to feel dissociative; being with people was sometimes a way of not being with myself. Social interactions were often accompanied by casual, moderate substance use of many varieties, smoothing over the edges of how it felt to be in my own body, my own mind. Craving depth, I’d sought out nightlife and dance-music spaces where the edges of consciousness and individual embodiment became ragged, where drugs and movement meant that people didn’t only touch; they smeared. People’s appetites—for connection, sex, embodiment, disembodiment—inflated and deflated, heaving and collapsing against one another.

If I was lonely, I was certainly less lonely than students at the university where I worked. They mostly dreaded gatherings—with or without substance use—and maintained tepid friendships, often out of convenience. The aforementioned Melanie’s nostalgia for friendship—from when she was in high school, before the pandemic—seemed continuous with a feeling that new friendships required intolerable discomfort. But this was not specific to Melanie. I noticed a general tendency to view all potential relationships not merely as anxiety-inducing, but as sites of possible betrayal. Many students reported loneliness while describing a feeling that people were only seeking transactional benefits, that closeness was intrinsically extractive, and that the risk of being used, abandoned, or mistreated was an obstacle to enjoying the kind of pleasant camaraderie typically associated with residential undergraduate life.

Many of the culture-industry and nightlife spaces I inhabited in the city were marked by an uncomplicated acceptance that relationships were partly or wholly transactional, whether it was about literal wealth, visibility, access, sex, drugs, or glamor. Sometimes in the city I felt like my students: aghast at the possibility that one might pursue intimacy in order to gain some secondary or tertiary material benefit. Other times, the specter of transactional relations felt like a dare, an opportunity to conjure genuine connection in spaces marred by anxiety about who’s who and who can do what for whom. Despite the harm of such economies and the capitalist relations they produce—intimacy defined by objectification and disposability—I saw rich romantic relationships and friendships flourish in the minefield of capitalist relations. For my students, even in the relatively flat, anonymous social world of the university campus, the possibility of transactional closeness seemed too unpleasant to contemplate. It was easier to not have a single friend than to accept the possibility that your friend needed something from you, or to hope you might help them in some way. In capitalist dystopia, relationships are an emotional liability. I wanted to understand where this pervasive fear of betrayal came from.

Part of the issue seemed to be one of trust, of whether it made sense to be open to others. Internet writer Rayne Fisher-Quann vividly explores how popular therapy discourse is often used to buttress a kind of isolationist personal politic, where we are quick to remove ourselves from relationships that are deemed painful or unpleasant. In an urgent dispatch from within the relational hologram landscape of the loneliness epidemic, Fisher-Quann argues that being with other people, rather than preserving one’s peace in their absence, is part of the path to personal development (and that relationships with therapists are not a substitute for other real intimacy—which, for the record, as a therapist, I basically agree with).

In 2018, edgelord social psychologist Jonathan Haidt co-authored the anti-cancel-culture manifesto Coddling of the American Mind. Despite the book’s dog-whistle-y lack of sympathy for college students upset by rape culture and racism, Haidt seems earnestly curious about young people’s mental health and their perceptions of safety and danger. He attributes contemporary trends in emerging adults’ social anxieties to a mix of factors, including overbearing parenting, ’90s television, stranger danger, and of course “tech.” Parts of his argument are compelling, like a critique of call-out culture on campuses because he thinks we shouldn’t fear our adversaries or rely on bureaucratic authority figures to settle disputes. Other ideas are near-sighted, such as addressing some of these issues by requiring high schoolers to learn cognitive-behavioral therapy tools. Like teaching incarcerated people mindfulness, while this may be a meaningful intervention, it is also clearly not a systemic or relational solution.

I think Fisher-Quann and Haidt are writing about the same thing, albeit one from the positionality of a young person trying to understand the shape of the world and the other from the positionality of a dad-vibe authority figure (who might have gotten yelled at by an undergraduate at some point and feels salty about it?). Both invite readers, and especially young people, to be tougher in trying to stay in community and in relation, to hold complexity and move towards difficulty, not away from it. And there’s something very moving to me about that, especially at a time when difficulty seems omnipresent.

Reading Fisher-Quann in particular, when I was already asking myself, “Am I lonely?,” I was reminded that closeness—not dissociative hanging-out-because-you’re-afraid-to-be-alone kind, and not the transactional socializing of people hoping to get something from one another—but real so-close-you-can-smell-the-decomposition-and-the-sweetness intimacy is both what I want and what I need to feel less alone.

*

My parents are introverted hippies, and they raised me (and my sister, five years older) in a secluded house in the woods, where they could read and garden in relative quiet. In my adult life I can’t always tell if I am lonely; when I was a kid, I knew that I was. When I was old enough, maybe ten, I would walk to the CVS in the strip mall about a mile from home—Haidt would say today’s kids would never be allowed—and sit on the carpeted floor reading music and women’s magazines for hours. Sometimes I would buy gum. As a young person I came to associate being in a store with trying to feel less alone.

These days, sometimes I turn off my phone, like all the way off, between 8 and 10 pm. The businesses closest to my house upstate are a vape store in one direction, a CVS in the other. Since I quit vaping in the spring, I sometimes walk to the CVS at night, often because I want something small (hair ties, micellar water). I’m not sure if it’s because the store is in an economically fucked-with area so they’re worried about shoplifting, or because it’s in an economically fucked-with area they are last in line for infrastructure upgrades, but either way, there is no self-checkout. This means I wait for the cashier, who is usually doing something else, to deal with me and my stuff. We tell each other “thank you” and “have a great night.” This is basically the closest thing to a social club near my house. In the warm months, a few blocks away, there’s an ice cream stand where people sometimes gather in the parking lot.

Shopping can be a very pleasurable way to be around people when you want to be partially but not fully alone. But it’s hard, in the place where I live—a poor, postindustrial, formerly thriving small city that has been battered by the flow of capital, in and then out, now undeniably unglamorous—not to feel the way that consumption and extraction of resources are threaded together with disconnection. Societally, as we have increased productivity to unbelievable heights, we have also discarded something: like my patients fear, the relational in favor of the transactional. In my town, and the smaller ones around it, early twentieth-century mansions that could possibly house a dozen or more people are literally collapsing, as five-over-ones with one- and two-bedroom units crop up where trees used to be, like an epidermal disease. The tremendous investment of resources into the explosive growth of capital is connected to a move away from interdependence. In such a framework, any human needs are liabilities—being vulnerable or dependent on someone else makes you less marketable. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy says we should invest in paid family leave and public transportation; he doesn’t say anything about a four-day work week, income inequality, surging consumer debt, or how the real wage hasn’t risen for 95 percent of Americans since the ’70s.

I don’t know anyone in my neighborhood very well so I don’t know how they feel, but I do know that despite living in a giant space for relatively little money, and despite not being bound by obligation to anyone for miles, I still experience other people as an inconvenience. The clerk at CVS takes too long. My elderly downstairs neighbor’s TV is too loud. When I meditate and try to notice everything nonjudgmentally, the neighbor’s TV stops being annoying, the murmurs of the news, no more, no less. But when I am trying to write or read, the sounds annoy me again. Loneliness is partly what it’s like to be a subject in an economic system where your emotional needs are either externalities to be minimized or incentives to be fused with commerce in an architecture of exploitation and extraction. Lately, I find myself wondering if I am lonely at the same time that I wish I were more alone—no neighbor, no cashier, more convenience, more quiet.

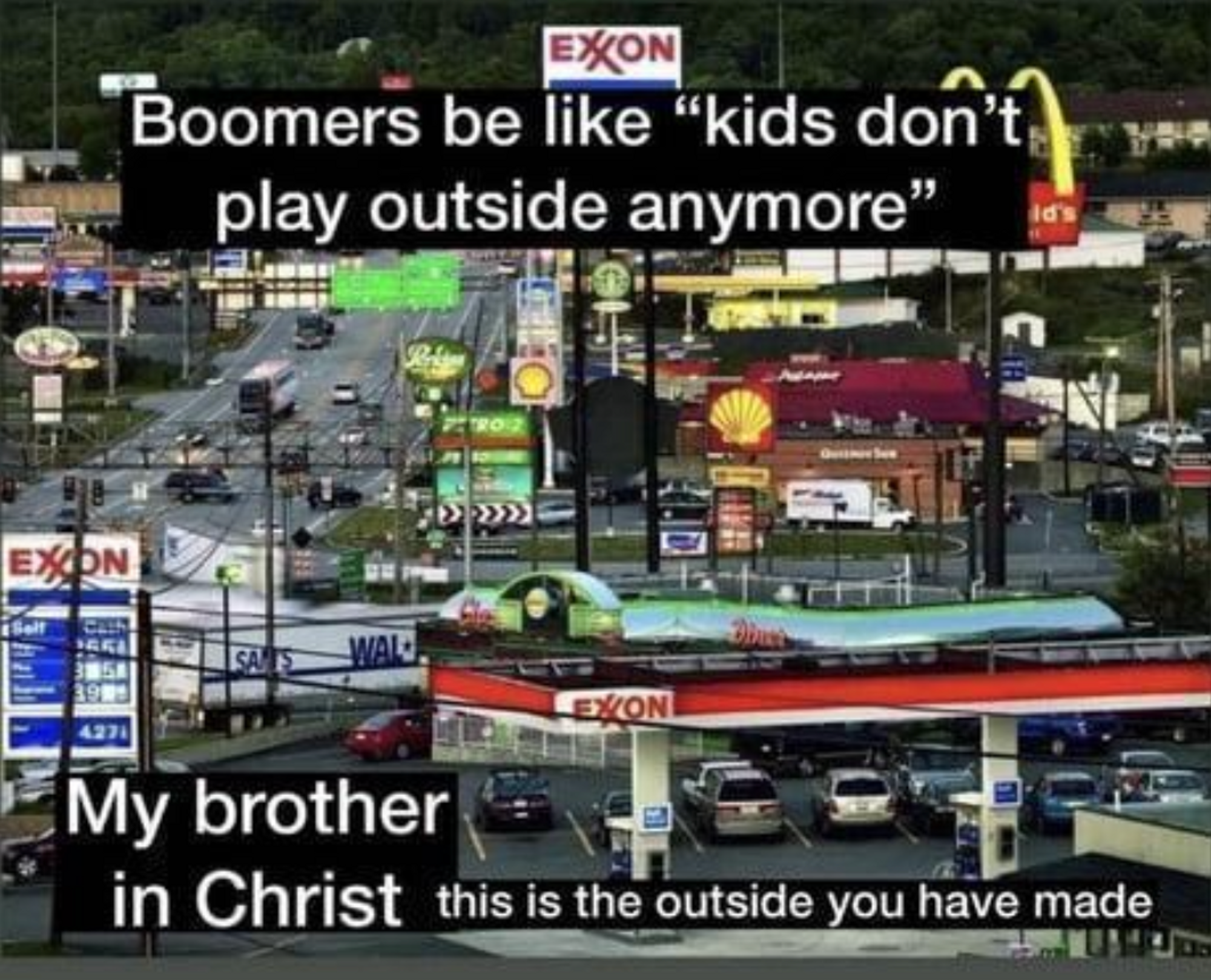

Desire gets tangled with dystopia; we are convinced that we want to be alone staring at our phones in the dark in our one-bedroom apartments, driving alone in our cars on a road with no traffic. The built environment, the options available to us, reflect back this interpersonal dystopia. As I wander around the partially vacant shopping malls in the next town over (my town is too poor to have a mall) my mind flickers from stories students have told me about their isolation to abstract macro-level data I’ve seen, and I picture an impossibly big, dizzying five-dimensional graph charting the emotional reality of mass loneliness.

*

When I was younger and spent more time doing more literal activist work—and was generally more critical of professionalized creative work—I imagined that my highest achievement in adult life would be a sturdy, interdependent, multigenerational non-nuclear family system. At that time, I led workshops about how oppressions are systemic, preaching that it didn’t matter what your individual attitude was; if you wanted to intervene on an oppression you had to intervene on larger systems. I remember talking to a room full of college students about this, maybe a decade ago, encouraging them to get involved in a campaign to curtail the many abuses of the NYPD. There are so many reasons, big and small, that I moved away from this kind of literal organizing, though the puzzle of individual and systemic factors braiding to form social reality still fascinates me. My thoughts return to loneliness.

I still want a non-nuclear family system; I wonder what shape it will take through time. It feels like something I want to grow or slowly move into, having spent a year detoxing—or maybe just pausing—from frenetic New York City socializing. At the beginning of the pandemic I read an interview with Naomi Klein where she said the lesson of lockdown was that we need expanded pods—that the people she knew who were thriving had larger, intergenerational units of connection. Part of radicalism, individual or systemic, social or political or familial, requires keeping an eye on the tension between where things are and where you (and your community) want them to be.

I encountered two new books this spring that discuss the abolition of the family with varying explicitness, one by therapist and activist M. E. O’Brien, bluntly called Family Abolition, and another, historian Kristen R. Ghodsee’s Everyday Utopia. I liked both of these books, and read them together at night double-helix, one a physical copy and the other on my e-reader, like two foods on a plate, taking bites back-to-back. I thought about both of the authors’ feelings a lot. Ghodsee animated her arguments by describing the violence in her nuclear family of origin in a way that I admired. I wondered if these authors were lonely, if that was why they were writing books about alternative social arrangements, ranging from community schools and eldercare programs to literal residential communes.

One thing Ghodsee helped me see is that people actually flourish with high levels of interconnection, whether in residential, educational, care, or labor settings, cooperatives, collectives, or cohousing settings. It’s simple and, when stated plainly, seems obvious. It’s also an idea that’s subtly but constantly disabused in our culture. Who hasn’t encountered the anxiety that any residential arrangement with spiritual, communal, or radical ties may be a cult that impinges on sacred secular individuality and its business partner (private property)?

Ghodsee notes that people often mythologize college as the best years of their life, partly because they get to live close to others, learn, and prioritize relationships. Working with college students—many of whom tell me that their primary tool for alleviating stress is being alone and watching TikTok—I wonder if they will mythologize these years. When they come to talk to me about their loneliness, I’m supposed to ask them nonjudgmental questions. I’m not supposed to tell them, “It’s systemic, you’re lonely because the system is broken. Another world is possible.”

I fantasize about engineering my life for more presence and connection: If I got a flip phone, how would the logistics of going out work; would I buy a standalone GPS device? If I wanted to call a ride-share car, would I ask a friend to do it and have them Venmo request me for the cost—then go home and complete the transaction on an iPad? I can’t figure it out. I am a little lonely, but I think I’m learning something because of it. I’m going to try having a roommate next year. I feel relieved that queer people get to ask these questions about radical adult life, that we stay connected in different ways because we may have different relationships to our families of origin, and might fail to adhere to the normative paths of adult relationships and community.

The thing about viewing crises systemically is that it doesn’t matter if you and your friends recycle, the planet is still warming. I want a queer separatist commune, but I know that constant mass shootings and astronomical suicide rates won’t be solved until all the “civilians” (what a new friend, who I incidentally met through long hours on the internet, calls cis straight people) are also living interconnected, nourished lives. There’s redemption in the insufficiency of individual solutions; it means that the presence of loneliness isn’t due to a failure of personal ingenuity. The feeling of isolation traverses interlocking tiers of culture, from individual psychology and daily habits, through tech and real estate developers’ blueprints on our devices and homes, to white flight and other politicized migration patterns, the laws about who is allowed to buy a gun and the cultural beliefs about what it means to have one, the cringiness of going to church and the fact that there aren’t very many churches left anyways.

In real life, I go to great lengths to avoid running into the students I work with outside of school. But in my imaginative life, I have wondered what it would be like to try to fix some of my loneliest students’ feelings by just hanging out with them, maybe walking in silence up and down the aisles of a CVS late at night, half actually looking for hair ties and half not wanting to go home just yet. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast