Digital Resistance and Monkey-Wrenching

Recent events have catapulted “protest” back into the American imaginary. I wrap the term in quotation marks because it is an unresolved term, a word which renders different images for different people, and which will continue to evolve and spill out into new forms as it has throughout history. It often conjures images of people marching down busy streets, shouting, and holding signs. This form of protest is an appeal to authority; if we demonstrate a shift in public opinion, our elected officials should enact new laws to reflect our desires. I do not mean to demean this avenue of politics since it is also a mode of protest in which I participate frequently. However, there is a reason to doubt its efficacy.

The 2003 demonstrations against the Iraq War protests remain the largest protest event in world history. Clearly, the war continued unperturbed by public opinion. The end of the Vietnam War is often described as the result of massive protests, though there is significant evidence that the US government was just as uninterested in public opinion then as it is now. The 2005 David Zeier film Sir! No, Sir! tells a different history of a GI movement that included American soldiers in Vietnam dismantling bombers before takeoff, so as to prohibit them from killing civilians. These instances of sabotage, along with mass refusal from soldiers to participate, is a more convincing story of the US withdrawal from Vietnam. This type of political activism is referred to as “direct action,” which makes no appeal to authority but rather exercises individual power to achieve a goal.

The unsanctioned removal of a Confederate statue is a perfect example of direct action. Rather than waiting for representatives to act slowly, if at all, citizens act directly on the material conditions of reality. As a media artist, I see direct action as a creative horizon that expands beyond the physical site of the street. Police, barriers to access, and countless other forms of oppression exist online just as they do IRL. Sites of conflict and engagement include platforms like Twitter, but also the means through which information itself is allowed to flow.

In 2010, PayPal stopped allowing donations to WikiLeaks after it published videos of the US military killing civilians in Baghdad with one soldier on the radio saying “Light ‘em all up.” The hacker collective Anonymous launched Operation Payback which included an attack on PayPal servers known as a DDoS, or distributed denial-of-service attack, which resulted in making the PayPal website inaccessible for one day, costing the company 3.5 million pounds.

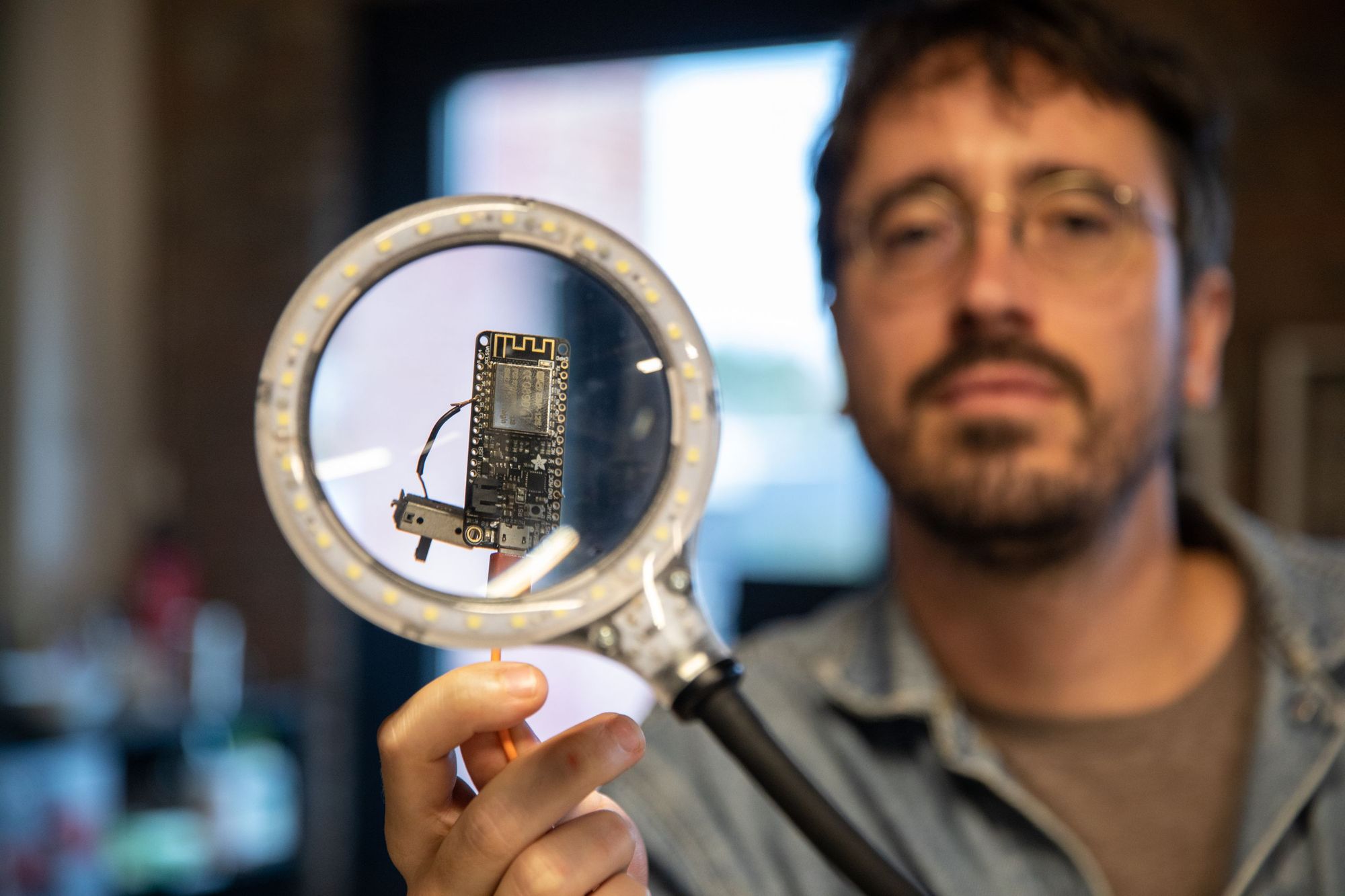

The projects described in this video are examples of novel modes of direct action, as well as artworks of the new media avant-garde. These projects are a model for moving beyond art that raises awareness about an issue but also towards cultural production that intervenes directly on systems themselves.

These projects in particular intervene on the systems and spaces in which they occupy: the digital space. FloodNet, the DDoS software that took down the World Economic Forum’s web server in 1998, positions itself both as performance art and an extension of the 1960s practice of “sit-ins.” The eToy war gamified the devaluing of an e-commerce company’s stock after the company sued the art collective over a domain name. SETI@Home, though not precisely activism nor art, created the means for a collective & distributed supercomputer to assist scientific researchers during a budget crisis. Bail Bloc, a distributed cryptocurrency mining application that bails people out of jail, is a detournement of financial speculation around cryptocurrencies.

I am cautiously optimistic that continued pressure aimed at every level of government will result in systematic change by defunding and then abolishing the police. However, it is important to keep in mind just how pervasive policing is becoming online, and with the aid of new digital technologies that look markedly different from a physical fleet of officers and cars. We must be vigilant in order to protect our privacy online, and continue to adapt and reinvent new modes of protest and insurgency in conversation with their adapted technologies.

Protests will spill over into virtual space, occupying new media and challenging the flows of information just as a demonstration in the streets reroutes city traffic and interrupts business as usual. People’s drones could broadcast the location of ICE agents; BIPOC-led investment cooperatives could leverage blockchain smart contracts to fund movement organizing and anarchist community spaces; and hackers could assist general strikes by creating wildcat tools that shut down internet access at work. Physical and immaterial protests must learn from one another, become interwoven, and potentiate new horizons of possibility. We must consider the horrifying obstructions of accessibility, state overreach, and global pandemics as creative challenges to overcome through trust and collaboration. And we must continue to do so now, while the iron is hot.

Subscribe to Broadcast