What's Your Pleasure?

Pippa Garner, Self-portrait in hospital after biking accident that disfigured her leg in Sante Fe, 2000.

I’ve never been the kind of person who orients herself towards pleasure. While raised Protestant, I have a Catholic sense of guilt and an innate inability to “just relax.” Recently, while driving back to New York City from Dia Beacon with my friend Frankie, I told her I wished I was more reckless. I couldn’t describe what it would mean to move towards this goal. Was it tactile? Sensual? Erotic? Chemical? A few weeks later in LA, the poet Rosie Stockton told me they were writing poems to discover the difference between love and desire. It seems an amorphous difference. The two share so many similar qualities. I told my boyfriend I felt like my life wasn’t moved by desire. “It is,” they said. “Just a different kind.”

Over the past few months the work of Pippa Garner has circled me like a huntress playing with her prey. From upstate New York to the Lower East Side to Joshua Tree to Los Angeles, I’ve trekked two coasts in search of Garner’s utopian pleasures. Her zany inventions—wearable stereo system-outfitted Blaster Bras, functional backwards-driving cars, classified ads, even her body—all exude a deep reverence for the joy of play, and range from the useless to the erotic; they always spin forward towards a new world, one ruled by femme-of-center androgyny. For Garner, the body is the ultimate playground, and bodyhacking is an experiment worth wagering fertility, class, marriage, and security on. “Gender tampering gets the conscious and the subconscious into a wrestling match,” she wrote.

Born in 1942 outside Chicago, the artist was the product of post-World War II suburban America. Her father was an ad-man breadwinner and her mother a “frustrated housewife.” After enrolling at the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena—intent on becoming an automotive designer—Garner became obsessed with cars and industrial design. She gained notoriety for Backwards Car (1974)—a stunt in which she drove a ’59 Chevy across the Golden Gate Bridge, its passenger compartment facing the wrong way—before touring the late-night TV circuit to talk about her speculative inventions. Eventually she began to transition, her body becoming her most intimate creation. This may account for the art world’s failure, until recently, to reckon with her legacy, though the ephemeral nature of her work is also difficult to monetize in the traditional art world. She’s only now getting her due with multiple shows across the country. “Act Like You Know Me,” which just closed at White Columns in New York City, topped off a slew of exhibitions featuring her work over the past year, including “$ELL YOUR $ELF” at Art Omi in upstate New York, “I’m With Me” at OCDChinatown in Manhattan, and “Made in L.A.” at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. Most of these exhibitions used Garner’s sketches of unrealized inventions as their primary motif, and walking by them was like walking past a comedy show; people tried to stifle their laughs until they realized Garner’s work is intentionally humorous. Her machinations toy with optimism like a mad scientist intent on one last magical discovery.

A comprehensive monograph on Garner’s work, $ELL YOUR $ELF, recently published by Pioneer Works Press and Art Omi, is one of two such recent books on the artist. The other, White Column’s ACT LIKE YOU KNOW ME, includes contributions from Fiona Allison Duncan, Dodie Bellamy, and Shola Von Renhold. $ELL YOUR $ELF was timed to coincide with her New York solo shows, and includes essays by McKenzie Wark and Jackie Ess. The girls clearly have a lot to say.

*

The way Garner treats cars is less straightforwardly erotic and more humorous than the abstract crash sculptures of James Chamberlain or the erotic collisions in David Cronenberg’s films; Garner enjoys teasing the macho world of car enthusiasts. Vehicles have been recycled into couches (Conversation Pit, 1973) and door frames (Chevrolounge, 1974). Recently, Garner devised Haulin’ Ass! (2023), a backwards pickup truck with oversized plastic testicles hanging lewdly from the back bumper.

From 1995 to 2010, Garner placed drawings of her inventions—many involving automobiles—in the magazine Car and Driver as “Ms. Goodwench.” But instead of providing greater efficiency or optimization, Garner’s products only mocked productivity. There was a door knocker designed to look like a penis, cookie-cutter templates for pubic hair, and the ability to text with one’s tongue. Other ideas included converting a family’s second-floor guest room into a garage by installing an access ramp, or hiding fire hydrants with fake trees to allow for more plentiful parking spots.

Pippa Garner, Chevrolounge, 1974. Automobile parts, couch, upholstery, dimensions variable.

These car-focused home goods expanded upon an earlier series of inventions from the 1980s, which were featured in Garner’s book Better Living Catalog (1982). No one seemed to understand her conceptual projects. They were considered dead ends. (Much like some consider transitioning to be.) A palm-tree umbrella’s leafy striations, demonstrated on TV by Garner, would hardly protect its user from rain. Her commodities flirted with capitalist absurdity, the commercial oblivion of “As Seen on TV” gizmos. To promote the catalog, she wore Half-Suit (1981), a midriff-baring tweed suit, for talk-show appearances (pre-transition). Pointless, simply pointless—yet so stylish too, an unwieldy and wild solution to a problem no one ever complained about. The consumer and the consumed critiqued and seduced.

*

In some ways, Garner’s gender transition echoes an attitude more common among trans people now than during the time of her first hormone injection. Setting aside questions of transness as a fundamental political identity, the question for her was, why not transition? Why not be open to change, to pleasure? Why not get big tits just for fun? Whether or not you conceptualize this axis as a political project shifts how much you enjoy Garner’s work. Is individual joy revolutionary? Many of us are still trying to find out.

Garner’s work is rarely written about under an explicitly trans rubric. Often she is placed alongside contemporaries like Ed Ruscha and other cis conceptual artists. But to avoid the gendered element of her work doesn’t do justice to pieces like the Crowd Shroud (2017), a small wooden box concealing a wheelchair. Her work breaks down binaries of public and private, voyeur and performer, boy and girl, useful and useless.

In more recent years, Garner has made an endless amount of shirts as her ability to fabricate large-scale work has declined with age. Shirtstorm (2005 to present) flaunts social convention. A daily practice, she flips and remixes common phrases to produce T-shirts that say “Guess my HIDDEN AGENDER,” “MAXED OUT ON MINIMALISM,” “AUNTIE CLIMAX,” “I need an inner child abortion,” and, one of my favorites, “Burn GALLERIES not calories.” Art Omi, OCDChinatown, and the Hammer Museum all prominently featured her shirts and sold replications. Like the popularity of Keith Haring’s work, this mass reproduction calls into question ideas of highbrow art, accessibility, and commerce. Ownership becomes oblique. Another favorite shirt: “I’m 70… but my tits are only 25!”

This sense of play wasn’t always welcome. Garner was kicked out of the ArtCenter for making Kar-Mann (1969), a small white sculptural car with hind legs raised as if to piss, and testicles hanging low where backwheels should be. The DMV in California wouldn’t let Garner change her license plate to SX CHNGE, though they did let her use HE2SHE—another example of how she continually winds her way around institutions that freeze her out, from museums to local government.

*

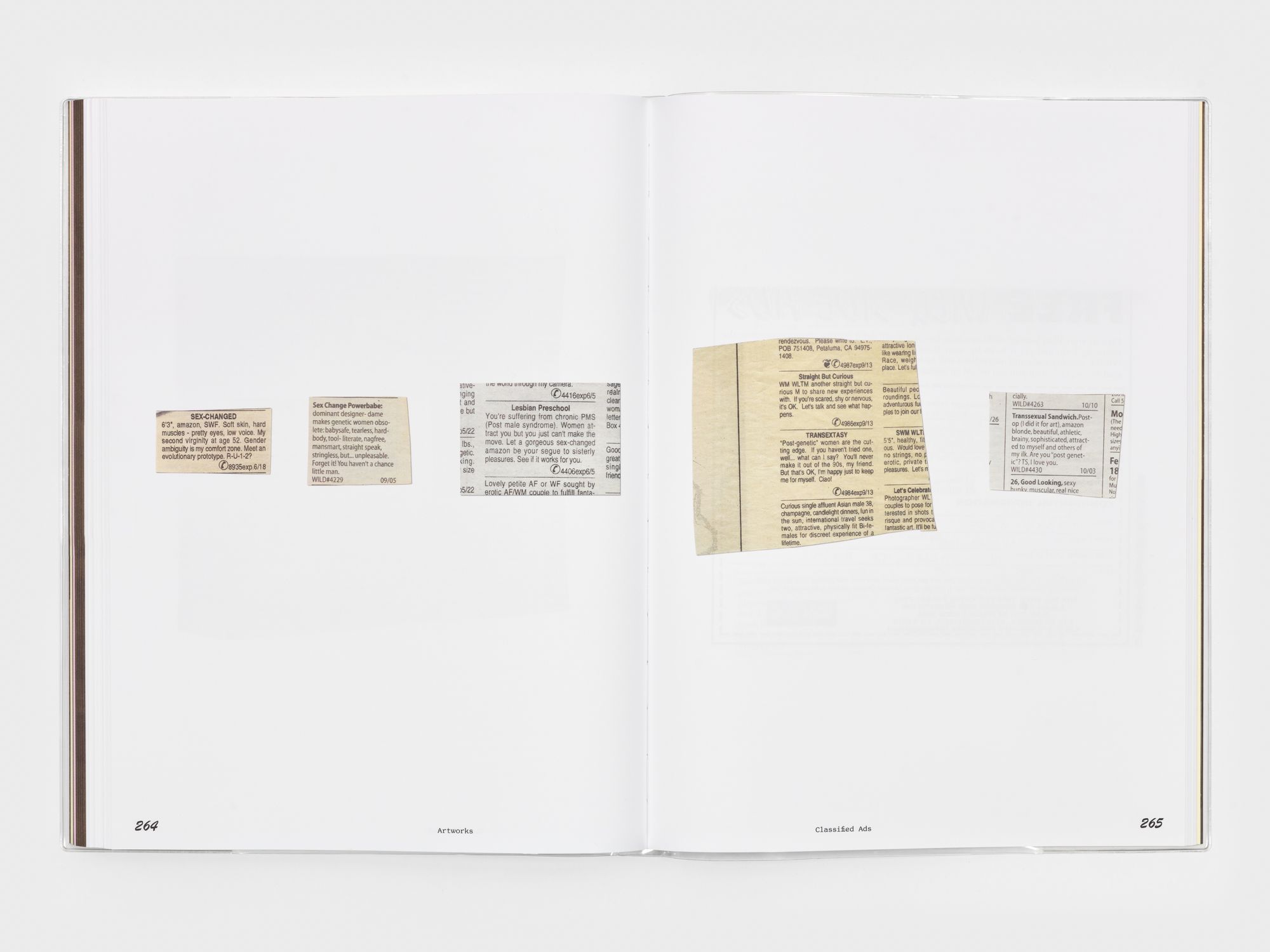

At Art Omi upstate, Kay Gabriel (the inescapable trans “it” girl) read the classified ads that Garner had placed in local newspapers not long after getting a vaginoplasty. In the write-ups, Garner sought a “fembryonic fun fest” for her “fully-programmable pussycat.” Her self-descriptors were a whirlwind of laconic self-confidence: “R-U man enough for freshly-minted Amazon blonde Gym-bunny with brains?” The transexual is a human built for optimum consumption, or at least, the kind of transexual Garner was referring to. The “doll” was surged up and ready for action. There was an almost combative sense to the ads: “You’re suffering from chronic PMS (Post male syndrome).” Her questions—“Are you fit, attractive, futuristic?”—postulated a utopia not of gender equality, but of estrogen over testosterone. (One curator told me he asked Garner about trans men only for Garner to look at him as if that was besides the point entirely.)

Taking Garner’s meandering writing too seriously may be a false start. “Balance can be stalemate as well,” Garner writes in $ELL YOUR $ELF, ever the provocateur. Androgyne is only helpful as a starting point. “Gendercide” is Garner’s goal: “To ‘be’ one of my own ideas.” One short story Garner wrote follows a man who suddenly grows breasts overnight only to try and cover them up during business meetings. Eventually he stops hiding and sells the concept to the board. Plastic surgeons eat it up—it’s a whole new market: tits for “cis” men. The capitalist underpinnings never escape Garner’s critique even if she doesn’t fully abandon them either.

A spread of classified ads from Pippa Garner, $ELL YOUR $ELF, 2023, Pioneer Works Press.

Later in the museum’s cafeteria, I heard a man sitting behind me refer to Pippa by the masculine pronoun. “There’s Pippa! He used to be a man. Or they. Or…” His wife, or female companion of some kind, didn’t correct him. She seemed even less interested in the process than he was. The entire time I was at Art Omi I was acutely aware of my body. I was a trans woman going on a trip to see a trans woman’s body of work in the middle of nowhere. Plenty of the work on display was explicitly tied to Garner’s body modifications—a highly decorated walker, writings about her surgeries, and videos of her life pre- and post-transition. It was nearly impossible not to be thinking about such mods. Without divulging too much, it is Garner’s playful attitude toward transition that has given me the space to step away from taking passing so personally. For too long I would cry on the subway tracks when someone clocked me, or worry obsessively about leg hair, tucking, or whatever random bodily dysphoria consumed me at the time. Garner offers a gentle reminder that it’s supposed to be fun.

*

After my trip to Art Omi and a visit to the bustling OCDChinatown gallery, I made a voyage to Garner’s home state of California. Not for business, at least not officially, but simply to see the sights. I hadn’t been to the West Coast in over three years. Besides, I wanted a solo trip and I needed a break. My world since the pandemic has been claustrophobic and closed to possibility, only occasionally punctured by hints of recklessness. I wanted to try and remember the contours of my body—and perhaps orient towards pleasure once again. I needed a place where I could crash with friends who knew me and go on long walks outdoors without freezing my ass off. I split my trip into multiple stops. First San Diego, then Joshua Tree, and on to LA.

While Garner is finally being recognized by institutions, her punk and DIY ethos still shines. You can tell she’s someone who cut her teeth in the trans club scene and made do in the Southwest. The same is true, though in vastly different contexts, of two artists I encountered while in California, Niki de Saint Phalle and Noah Purifoy. Their works evoke a dystopian-utopian edge similar to Garner’s, piercing the mundane with ethereal interventions into public space. Saint Phalle is the queen of joy. Her colorful work, abounding with vibrant patterns, sickening colors, and rotund shapes, are all over San Diego, where she lived out her last years after a life spent around the world. Purifoy’s permanent desert exhibitions can be seen from miles away. I hadn’t expected to encounter either of them; when you’re traveling, so much is outside of your control. You must relinquish yourself to your own curiosity.

In San Diego, my friend Russell and I went on a hunt to see all the Saint Phalle we could. (Why? For fun.) As Russell’s kid played around her statues of baseball players and gators, we gazed at the endless pieces of tile and mirror affixed to them. Snakes wind around the black-and-white checkered walls and strange pillars rise up above the marbled ground. Her sculpture garden in Escondido was our last find—it is only open three hours twice a week, and only if it hasn’t rained the day before. The result was magnificent, a strange Alice in Wonderland-like enclosure in suburban California.

After San Diego we went to Joshua Tree, a completely alien landscape to a Hoosier like me. The desert was not as flat as I’d imagined, nor as arid. Cacti and the eponymous trees rose amid pieces of steel and charred buildings. We arrived late at night after trying a variety of Chamoy candies from the 7-Eleven. In the dark it was hard to make out much. We slept in a tiny hundred-square-foot cabin. When I woke up, I walked around in heels and a skin-tight flesh-colored dress. I poked around a burned building and saw a shredded mattress before I walked back to Russell, who was fixing a broken pane of glass. We got coffee and eggs in town. We wandered the Art Queen (modeled like a Dairy Queen, but with embroidered shirts), the World Famous Crochet Museum (a store of undyed garments for obscene prices), and all the health food stores I could ever want.

We then drove to the Noah Purifoy Desert Art Museum of Assemblage Art. There should be more critical writing on Purifoy. Born in Alabama, he started making art during the 1965 Watts Rebellion. He was a Black sculptor with a fondness (not unlike Garner) for Duchamp. He lived primarily in California, working on a fifteen-acre desert property in Joshua Tree for the last fifteen years of his life. The resulting sculpture garden is haunting and dizzying in scope. Multiple auditoriums are set up, strange in their eerie emptiness under the blank blue sky. Makeshift sectioned-off graveyards and toilet sculptures adorn the desert floor. A drinking fountain for whites only is next to a toilet. Shelters are filled with computer parts, busts, and beds. We walked around in silence before driving back through the desert to the City of Angels.

*

LA was not for me, it felt normcore with an athleisure twist. Everyone spent a lot of time trying to convince me that I should move out West but few people could summon up convincing reasons.

“Taxes,” Sarah Rose Etter told me.

“I still can’t figure it out,” a friend, Rosie, said.

“The space,” many claimed.

But the highlight was seeing Pippa’s work at the Hammer. It was the punk trick I needed. Her shirts winked back at me mischievously. I thought about seeing if she would be down for a visit while I was in town but that felt intrusive, opting instead to look at her sketches of Lindsay Lohan on the museum wall. Everyone was obsessed with her T-shirts. They commodify an anti-capitalist aesthetic, allowing a kind of anarchic posturing. Her exuberance and magnetic presence stood out alongside many other incredible artists, like Miller Robinson, Ishi Glinsky, Kang Seung Lee, and Akinsanya Kambon. Somehow it reflected something about the smoke and mirrors of LA, but I couldn’t put my finger on it. Many artists reflected on the land, gentrification, gender, or industrialization. Pippa seemed to nod at all of these machinations. Driving over bridges, refusing optimization, deconstructing the body. Everyone in LA is a hobbyist and a careerist, playing two contradictory roles on a technicolor set fading into dusk.

*

Tattoos are one way of reclaiming the body. After a trauma, they can serve as reminders of autonomy. After a car crashed into Garner’s bike, her leg felt stiff, “almost wooden—no longer her own.” The tattoo artist Dawn Purnell helped devise a wood grain design for Garner. Tattooed underwear soon followed, a light purple bra and a thong with money hanging out. She also got a tramp stamp that looked like a Post-it with the phrase “I is a Ass.”

A beautiful self-portrait of Garner in the hospital, taken shortly after the crash, features her taut abs, supple breasts, a nose ring, painted nails, flowing hair, arms crossed with metal supports, and a hospital admission bracelet clearly visible. She stares back at the camera defiantly, oozing a serious eroticism in the hospital bed. The making and remaking of the body continues long after transition.

OCDChinatown offered tattoos of Pippa’s work during Garner’s exhibition. A small group of trans artists and willing participants were paired together. I was paired with Zyra West. The catch was that we had to be willing to be tattooed publicly. My slot was during the opening. Voyeurs welcome, the invitation said. I invited my boyfriend and my friend Agnes to come watch. I wore a shiny light blue slip that my new breasts filled out nicely. I stared at the ceiling as Zyra started on my arm. It was my first tattoo with a gun; all my others have been stick and pokes. I received a detailed finger with a lit cigarette piercing through the nail. Now Pippa is with me wherever I go.

There’s a decadence to Garner’s work. A luxury in the ability to subvert class and hegemonic gender. It’s no walk in the park, but it’s something. My boyfriend has continually nudged me to try and let pleasure into my life. From simple logistical things like rugs and lamps to the joys of Diet Coke or eating dessert. (Trans women are unfortunately known for fighting eating disorders. I am no exception.) But I’ve also been thinking these past few months about how to be more open to life writ large. Garner, if anything, continually throws herself into the impish work of tinkering, inventing, and creating. How can I be more open? I thought going on a little slog through the desert would help, and in some ways it did. But by the time I got home there was also joy in laying down, making gochujang soup, having a quiet night in, and reading about people whose lives are far more interesting than mine. Maybe that is enough, because there is a pleasure in that too. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast