God Is in the House

I — PILGRIMS

Twenty years ago, I lived for a year in a house across from William Faulkner’s Rowan Oak in Oxford, Mississippi. My office was in the attic, a room bigger than my whole apartment in Brooklyn. My desk sat in front of a window and at intervals ladybugs with rust backs and black spots streamed out of the window frame. They’d gather in a shifting pile and then crawl out across the glass onto the green vine wallpaper. I often thought, by the way they swooped and curved, that they might form letters, then words and finally a sentence from a wild god.

This never happened. Instead I watched Spanish moss hanging like long scarves from the giant cedar in my yard and, behind the tree on the road, buses filled with senior citizens come to tour Faulkner’s Greek Revival house in Bailey’s Woods. Sometimes the pilgrims were from other countries: busloads of Irish and French people on vacation. I watched them de-bus, walk the driveway covered in small blonde stones, pass the boxwood hedge maze and the giant magnolias with their thick, shiny leaves and creamy-petalled flowers. Inside they’d find portraits of Faulkner’s ancestors as well as dark wooden Victorian furniture. In the writer’s office they’d gape at the outline for A Fable written directly on the walls and Faulkner’s Underwood typewriter sitting next to a tin of pipe tobacco on his desk. I most cherished the items and details that brought Faulkner back to scruffy life: a crappy plastic shoe rack beside his bed and, in the kitchen, pencilled phone numbers written around the black rotary phone.

Every night at twilight, I walked with my three-year-old daughter over to Rowan Oak. She would chase rabbits around the boxwoods and, as it got darker, try to catch fireflies. Sometimes we’d find offerings on the steps: a red rose, a white rose, a pair of fake false teeth, a tiny plastic coffin.

The pilgrims came in every season. Most compelling to me were not the busloads of people but the seekers who came on foot, alone or in pairs. I assumed they’d travelled to Oxford by Greyhound bus and walked all the way from the bus station across town. Some were in ordinary clothes but the majority of them, and this at first surprised me, wore black. I would look up from my legal pad to find a tall young man in a black velvet jacket, tight black trousers and knee-high black lace-up boots. I remember a girl in black leather trousers, a blouse with large bell sleeves, a black ribbon around her neck. Another young woman wore black lace gloves to her elbows, a long black dress and Doc Martens.

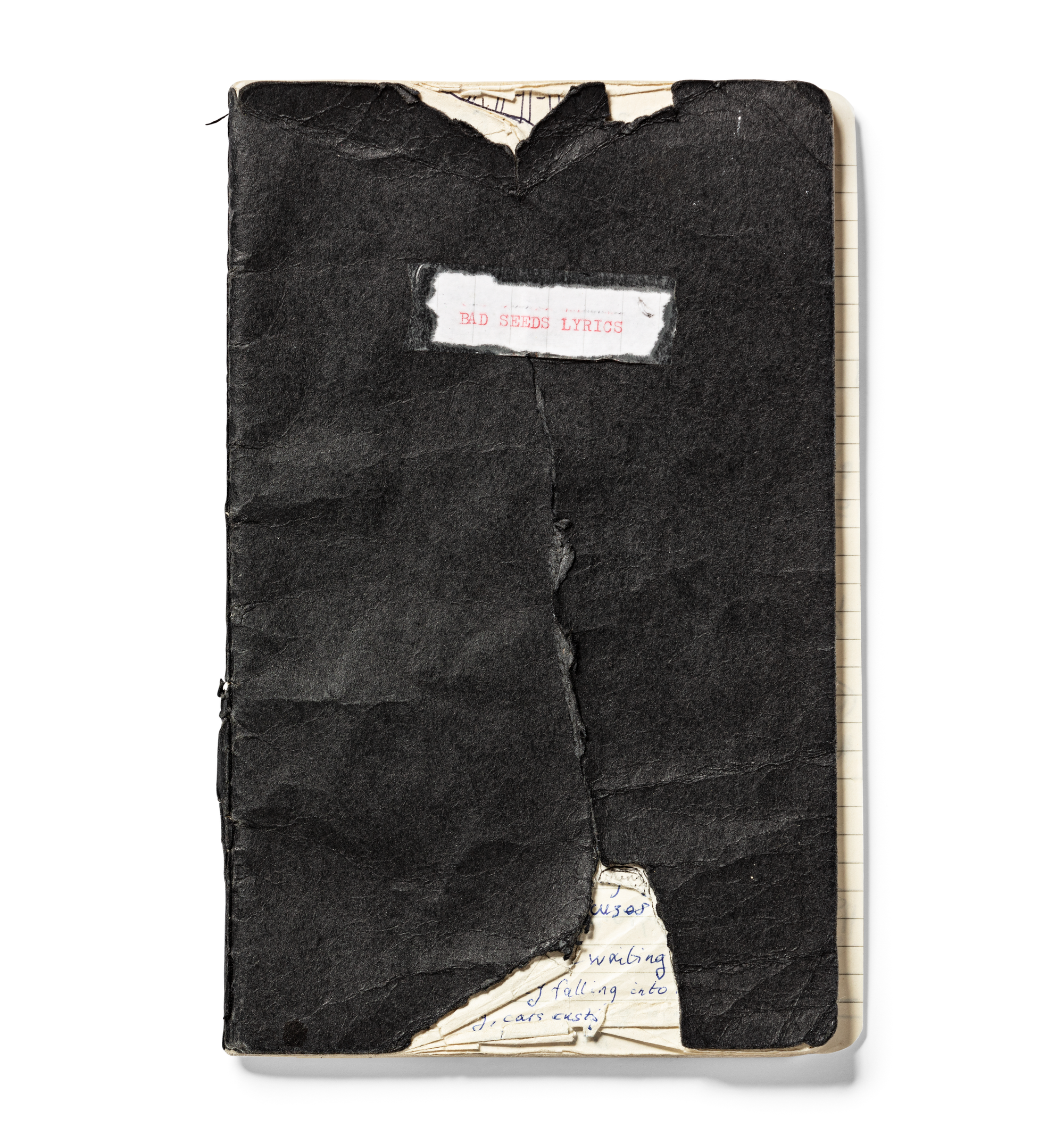

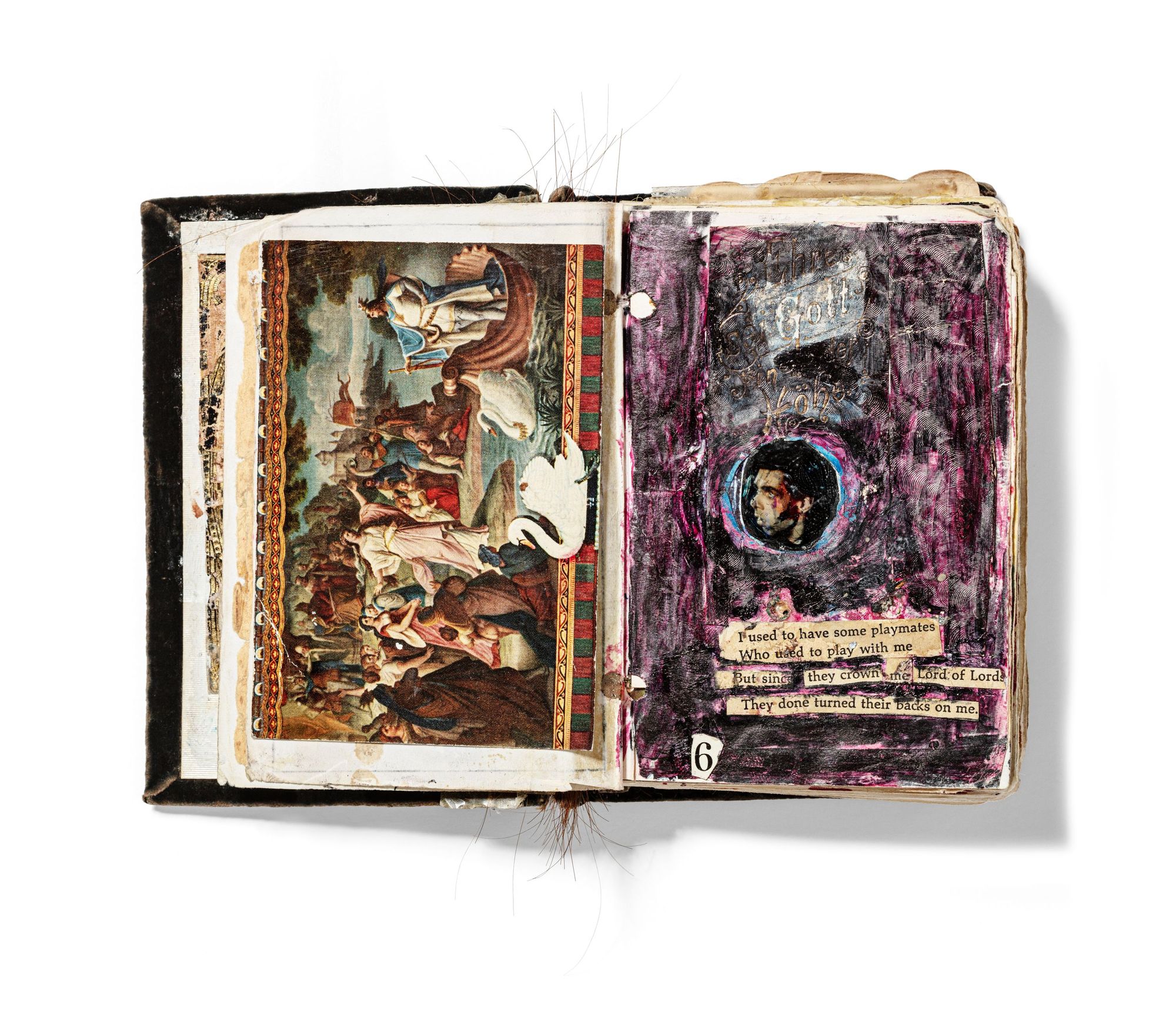

Of all the young pilgrims I saw that year the one who most stays in my mind is a Japanese boy in black high-top tennis shoes, black jeans and a Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds t-shirt. He walked fast and with a look of stricken anticipation. I had the feeling his journey had been arduous and that his longing was close to overwhelming him.

I didn’t see the boy leave Rowan Oak; I’d had to pick up my daughter at pre-school, grade papers, make our dinner. When we walked over later in the near dark we found on the steps, in the usual offering spot, a copy of Nick Cave’s novel And the Ass Saw the Angel in Japanese.

I have spent a lot of time in the intervening years thinking of those black-clad kids, moving diligently and with joy under the draped moss, past banks of kudzu toward their particular mecca. I understand why they were drawn to Rowan Oak and to Faulkner: his lyric prose, his cast of suffering and deeply human characters, but most of all what Albert Camus called Faulkner’s ‘strange religion’. A religion that knifed open metaphysical questions and split the human heart. ‘What goes on up there,’ Cave writes in And the Ass Saw the Angel, ‘what measure the affliction? What weight the iron? Is it a chance system? ... or —anti-creation, something seasonal, something astrological?’

What is God? What does it mean to bear witness? Where do the dead go? Does the divine world exist? Does it fit with the human world or are they separate? What does it mean to be good? Cave’s characters, like Faulkner’s, often blend the earthly and the heavenly. ‘No God up in the sky’ Cave sings, ‘no devil beneath the sea/Could do the job that you did, baby,/ of bringing me to my knees.’ Cave’s songs often undermine and negate religious adoration and instead, though we may be too blissed out to realise it, confront us with lush far-reaching theological questions.

John Keats claimed that the best writers all had a love of questions, of paradox, of what he called ‘Negative Capability, that is, when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.’

Both Faulkner’s and Cave’s characters reside in paradox, filled with doubt, longing, questions, frustration. Faulkner’s paradoxical religious outlook ‘invested brothels and prisons with the dignity of the cloister.’ And Cave is ‘“agitating” for a broader definition of the human, one that incorporates lapses into the human, incompleteness, a certain dilapidation and impoverishment of the soul’. Both see human/god relationships as complicated, fraught. Apophatic theological belief is found, if at all, piecemeal, murky, a grasping through darkness, never in the light.

‘All the best people,’ my friend recently said to me at our red wine lunch, ‘are dinged up a little.’ What makes a living person or a fictional character unique is not perfection but their flaws and scars.

God’s redemptive gift of grace can be experienced in Cave’s songs by anyone, the more dinged up the better: a killer on death row (‘The Mercy Seat’), a john (‘Jubilee Street’), even a man who may or may not have murdered his entire family (‘Song of Joy’). Like Faulkner’s ‘strange religion’, Cave is not interested in easy born-again redemption. Those black-clad young people were not pilgriming toward fixed meaning, certain divinity, systems of truth. No. They were drawn like particles toward a magnet, like an electrified atom of authentic mystery, to a raw–almost bloody–sensitivity, to an awareness ‘in which life itself is lived more intensely and with a meaningful direction’.

William James, the nineteenth-century philosopher, speculated that belief was a form of magnetic energy that pulled the believer almost unconsciously in one direction or another. ‘It is as if a bar of iron, without touch or sight, with no representative faculty whatever, might nevertheless be strongly endowed with an inner capacity for magnetic feeling; and as if, through the various arousals of its magnetism by magnetic comings and goings in the neighborhood, it might be consciously determined to different attitudes and tendencies. Such a bar of iron,’ James continues, ‘could never give you an outward description of the agencies that had the power of stirring it so strongly; yet of their presence, and of their significance for its life, it would be intensely aware through every fibre of its being.’

On Sundays Faulkner intermittently attended the Episcopal church in Oxford, but according to local legend he also, after all-night drinking binges, rode his horse wildly around the town square while the rest of Oxford sat in church. And Faulkner, as well as Nick Cave, casts a spell on you, like a prehistoric shaman, who meshes the reader in numinous symbols and sacred horror.

My favourite Faulkner character, Addie Bundren from As I Lay Dying, speaks only after she is dead. Many of Cave’s most unforgettable characters, from The Birthday Party’s ‘She’s Hit’ to the Murder Ballads’ ‘Henry Lee’ and ‘Where the Wild Roses Grow’, to Ghosteen, are voiced only after they are gone. Addie haunts her family, who must carry her dead body in a pine coffin into town. Before she dies, one of her sons describes her eyes. ‘Like two candles when you watch them gutter down into the sockets of iron candle-sticks.’ Addie’s female body is an affront and a challenge to masculine culture. Outwardly she has conformed to traditional gender construction, though her inner life is complete rebellion.

She has had an affair with the minister, Whitfield, and her child with him is her favourite son Jewel. Addie’s friend Cora abides by traditional Christian standards, while Addie is punk rock, rejecting the Christian ideal of human suffering as the price one pays for the privilege of eternal life. ‘The duty to the alive, to the terrible blood. The red bitter blood boiling through the land.’

Cave’s song ‘Nobody’s Baby Now’ has always reminded me of Addie, a seeking soul, who turns away from both human convention and restrictive religion to face an implacable God. ‘I’ve searched the holy books/Tried to unravel the mystery of Jesus Christ, the saviour/I’ve read the poets and the analysts/Searched through the books on human behaviour/I travelled the whole world around/For an answer that refused to be found/I don’t know why and I don’t know how/ But she’s nobody’s baby now’. Later lines from the song could be spoken by Addie’s son Jewel. ‘And through I’ve tried to lay her ghost down/ She’s moving through me, even now.’

In And the Ass Saw the Angel, the hero Euchrid Eucrow speaks, like Faulkner’s Addie, out of silence. While Addie speaks from beyond the grave, Euchrid is a deaf mute, the only surviving twin born to an alcoholic mother into a mythical landscape with hints of the American Deep South as well as rural Australia. ‘Tall trees born into bondage rising from a ditch and crabby dog-weed, carrying a canopy of knitted vine upon their wooden shoulders.’ Euchrid is ‘jettisoned from the boozy curd of gestation’ into the Ukulite Congregation, a group of Amish/Mormonlike zealots. In his silent world Euchrid is ‘the loneliest baby boy in the history of the world ...’

The God of the novel is the Old Testament God, and interactions with him bring Euchrid fear and trembling rather than peace. And as Cave has written, ‘I believed in God, but I also believed that God was malign and if the Old Testament was testament to anything, it was testament to that.’

Euchrid is shunned, beaten up and despised by the Ukulite faithful but also by anyone else he comes into contact with. His lamentations contain some of the most beautiful writing in the book. ‘Ah was deemed unworthy of the organ of lament. Ah am not one to bemoan mah lot. But even Christ himself was moved to loosen the tongue of his wounds.’ And in Lamentation 3: ‘Even now as ah inch under, something rushes at me. Something of the hellish reason-evangelists hooded scarlet came, turned vigilante with bloody deed done.’

Euchrid is kin to John Harper in the 1955 film The Night of the Hunter. Both are boys living in a world of false prophets and over-heated faith. Harper must protect his little sister Pearl against a widow-killing convict with the words HATE tattooed on the fingers of one hand and LOVE on the fingers of the other. After Powell murders their mother, the children climb into a boat and float into an uncanny night journey on glittering black water. It’s hard to tell if the river is redemptive, or that doomed transitional waterway, the River Styx.

‘Hell,’ Flannery O’Connor wrote in A Prayer Journal, ‘is a great deal more feasible to my weak mind than heaven.’

And the Ass Saw the Angel does not let up on injustice and hellish atrocities. Still, it’s Cave’s rich atavistic language, idiosyncratic and imaginative, that is ultimately redemptive. ‘Language itself,’ Cave has said, ‘can have a hugely beneficial effect on you in the same way music can.’ Rebecca, a character in the novel, comes ‘through her back door, wearing only a night dress and carrying her spirit lamp, she crept like a bird into the night’. And Euchrid’s empathy for the earth is acute and beautiful. ‘All about me the world seemed in need of attention.’

‘A proof of God is in the firmament, the stars ...’ Faulkner once wrote, ‘proof of man’s immortality, that his conception that there could be a God, that the idea of a God is valuable, is in the fact he writes the books and composes the music and paints the pictures. They are the firmament of mankind.’

‘Slippery as religious experience,’ writes Maud Casey in her book The Art of Mystery, ‘mystery involves an undoing that yields wonder.’

‘For me,’ Cave told an interviewer for BOMB magazine, ‘belief comes from the place that inspiration comes from, from a magical space, a place of imagination.’

II — HOLY JUMPERS

‘Faulkner wrote about twelve ministers,’ the religious scholar Charles Reagan Wilson wrote, ‘three heavy drinkers, three fanatics, and three slave traders, two adulterers and two murderers.’

God, as they say, works in mysterious ways.

My grandfather, the Reverend Arthur Ferdinand Steinke, neither drank nor killed anyone, though he was foreboding and very Old Testament. His church had a tall white steeple and a metal cross on the brick façade. He was a sombre Lutheran minister who loved to wear his black Martin Luther cape and slouchy hat. A fire-and-brimstone preacher, as he got up into his eighties he didn’t talk much but he still loved to preach. Even when he had to be helped up the steps into the pulpit, his voice boomed, his face reddened, and he sweated. His sermons often spun out into diatribes about how the Christian faith should use the symbol of the electric chair rather than the cross, which chimes eerily with the imagery in Cave’s song ‘The Mercy Seat’. Sometimes my grandfather fell into a time warp, telling women to get over their addictions to nylon stockings, and men to new car tires. His signature sermon was one in which he held up a silver dollar and asked someone in the congregation to come and claim it.

Nobody would, not the ageing male ushers, not the church ladies in their pastel Sunday suits, not the young mothers or the teenagers. We were all terrified of him. After ten excruciating minutes he began berating us for our lack of faith.

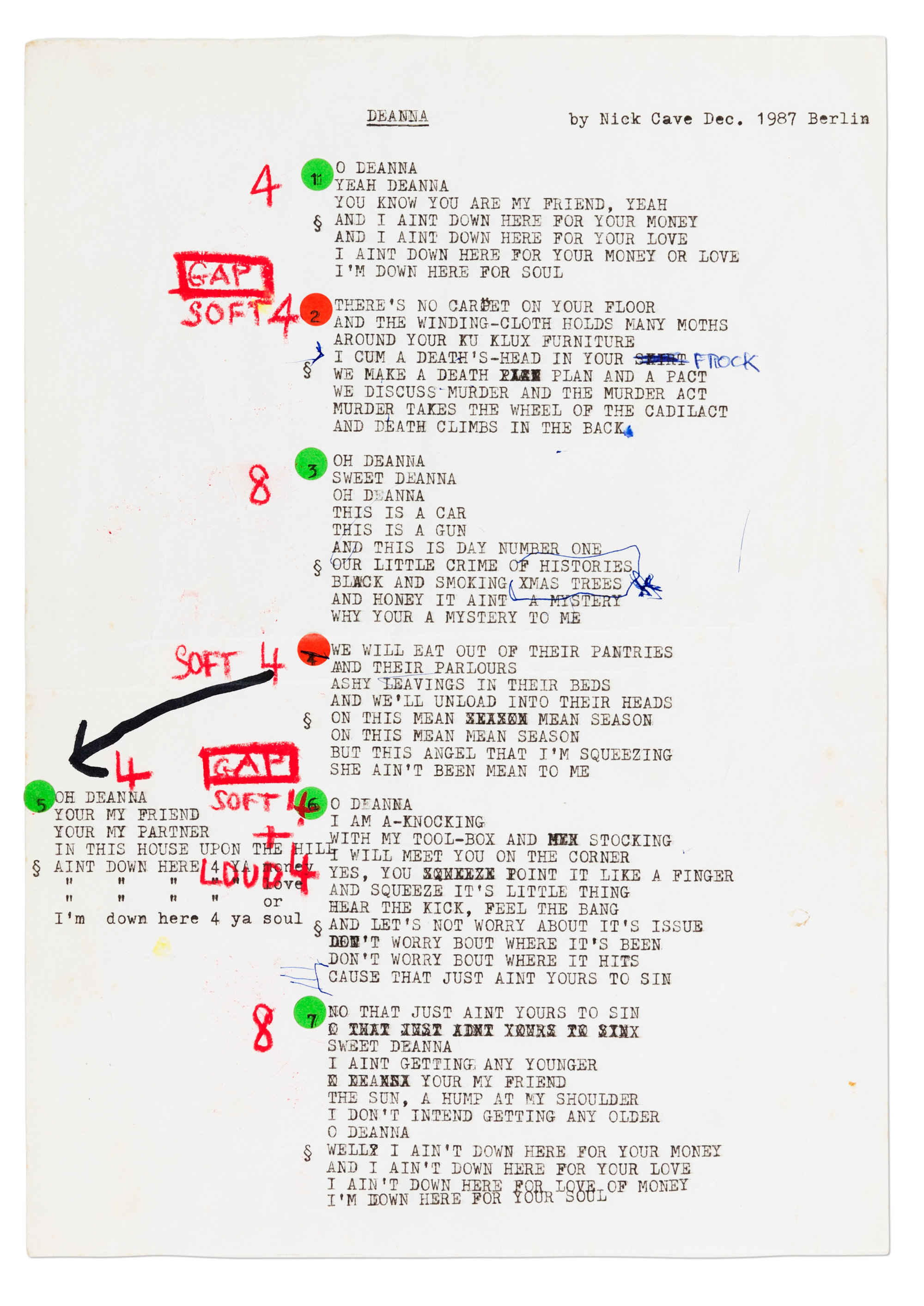

What does it mean to be Old Testament? To identify with its punitive and inchoate God? The Old Testament seems to have given Cave permission; extreme texts can open up a writer to a freer and more expressive way of working. ‘When I bought my first copy of the Bible, the King James version,’ Cave writes in his introduction to The Gospel According to Mark, ‘it was to the Old Testament that I was drawn, with its maniacal, punitive God, that dealt out to His long-suffering humanity punishments that had me drop-jawed ... at the very depth of their vengefulness.’

In his early years Cave channelled the Godhead of the Old Testament. ‘All I had to do was walk on stage and open my mouth and let the curse of God roar through me. You could smell his mad breath.’ In Cave’s imagination the Bible became a magic book, enchanted but also dangerous. You could ‘see the yellow smoke curl from its many pages, hear the blood-curdling moans of despair.’

So much of the power in Cave’s lyrics is in the way he declaims them. In his black suit, the microphone in his right hand, and his left pointing out over his congregation, Cave stalks the stage, sometimes falling on his knees to touch the hands raised up in hallelujah. What makes his presence so mesmerising is that while he evokes a tent preacher, he is also sexual, gothic, and his message, unlike an Old Testament preacher, damns no one; it is nuanced, complex and empathetic.

Cave in later writings linked the nihilistic rage that permeated his early songs to blocked grief. ‘I see that my artistic life has centered around an attempt to articulate the nature of an almost palpable sense of loss that has laid claim to my life. A great gaping hole was blasted out of my world by the unexpected death of my father when I was nineteen.’ Cave learned to fill that ‘hole’ by writing.

The gnostic concept of an impotent and evil God whose melancholy and rotten creation mirrors his own badness seems to be part of Cave’s earliest theology. Many of the songs are staged in a mythic place much like the Southern United States. The South in this myth is Old Testament, punitive, conservative, wounded. A grim Calvinism injects the area with literal readings of the Bible, as well as an obsession with mortality.

In Mississippi, my next-door neighbour was an Italian translator who was working on court transcripts of John Calvin’s trials. These took place in Geneva in the 1500s. She told me about a young woman who had accidently broken a vessel filled with olive oil and in fear of what her master might do to her had jumped into the river. Because suicide was, according to Calvin, a crime against God, she was tried and hanged. This fragile drenched ghost often comes to me all these centuries later, a slave girl, standing in front of a court filled with men. Calvin would have railed on, much like my grandfather, about the sovereignty of God and the depravity of man.

‘No bolder attempt to set up a theocracy was ever made in this world,’ wrote cultural critic H.L. Mencken about the South, ‘and none ever had behind it a more implacable fanaticism.’ What would I say if I were that slave girl persecuted by Calvin and his idea of a rule-obsessed and punitive God?

Cave’s ‘Big-Jesus-Trashcan’ would be a good place to start. Cave snarls ‘Right!’ as the song begins, signalling that court is in session and it’s not the sinner but the Church’s crappy theology that is on trial. The sin of the Church is its failure to come to terms with human nature, to think it is better than the people it serves. ‘Big-Jesus-Soulmate-Trashcan a fucking rotten business this.’ There is anger but also sorrow for the sorry state of the Church. This melancholy manifests in both rage and absence. Jesus, as he is embedded in the Church, is a malevolent figure who pumps Cave ‘full of trash’.

Punk, to my mind, differs from heavy metal by both its sly humour and its irony. Also its nuanced theological engagement. While much metal takes on the mask of destroyer, punk is the wailing of the destroyed. A Bible website lists scriptures that support the existence of punk rock: 2 Timothy 4:2, ‘Preach the word; be ready in season and out of season; reprove, rebuke, and exhort, with complete patience and teaching’; Ephesians 5:19, ‘Addressing one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody to the Lord with your heart’; and my favourite, James 1:8, ‘He is a double-minded man, unstable in all his ways.’

Darkness doesn’t have to be nihilistic. Cave has often denied that his songs are negative, and in interview footage from the 1990s he says that rather than asking him why his lyrics are dark, people should ask Bruce Springsteen why his lyrics are happy. The mystic St John of the Cross taught that only through what he called the Dark Night could we ever understand ourselves and that the purest form of God is absence. Only by deconstructing our meta-narratives about God can we get closer to the divine mystery.

Our ideas about God, Gerald G. May writes in his book about St John, ‘are only messengers. Instead, we take them for the whole of God’s self, and thus we wind up worshipping our own feelings. This is perhaps the most common idolatry of the spiritual life.’

‘I do not know you God,’ writes Flannery O’Connor, ‘because I am in the way. Please help me to push myself aside.’

In both St John’s poetry and Cave’s lyrics emptiness is the beginning of something; it is generative. ‘You fled like the stag after wounding me,’ writes St John, ‘I went out calling you, but you were gone.’ And Cave: ‘The same God that abandoned her/Has in turn abandoned me.’ The spiritual path is one of subtraction; we are slowly but conclusively emptied out.

‘The kind of sadness that is a black suction pipe extracting you,’ writes Anne Carson, ‘from your own navel and which Buddhists call/“no mind cover” is a sign of God.’

‘The religions which have a conception of this renunciation,’ writes theologian Simone Weil, ‘this voluntary effacement of God, his apparent absence ... these religions are true religion.’

Weil says: ‘Grace fills empty spaces but it can only enter where there is a void to receive it and it is grace itself that makes this void.’

‘Big-Jesus-Trashcan’ attempts, like all punk, to harness the life force, or rather, the band becomes a conduit for that wild force. This power is not strictly positive–it’s a mad energy that pushes up tulip tendrils, moves babies out of mothers, gives poets ideas but also fuels anger, violence, even bloodshed. The life force is as much part of a seed sprouting as it is a body chemically breaking down after death.

For Cave, it’s this same wild rush of spirit that also fuels rock’s beginnings. These myths in Cave’s telling are both enchanted and ominous. In ‘Big-Jesus-Trashcan’ Elvis makes an appearance: ‘wears a suit of gold (got greasy hair)’. In the next line Cave sets up a sort of competition with Elvis, an anxiety of influence that will continue throughout all the years of his songwriting: ‘But God gave me sex appeal.’

Elvis is the Jesus of rock and roll. Of course we have the earlier myth of Robert Johnson meeting the Devil at a crossroads, as retold in the song ‘Higgs Boson Blues’ on Cave’s album Push The Sky Away. Johnson seems to sell his soul so that musical divinity in the form of the blues, rock’s predecessor, can enter the world. It’s the African American blues men and women who are both the founders and the saints of rock’s Church. But Elvis is Jesus. Stanley Crouch, a critic, has called Jesus’s last line on the cross–‘My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me’–the greatest blues line of all time. Like Jesus’s, each part of Elvis’s life has been fetishised, mythologised, made into scripture.

‘Myth,’ Cave writes in his poem The Sick Bag Song, ‘is the true history.’ In his song ‘Tupelo’, Cave both retells and electrifies the myth of Elvis’s birth. First thunder and hard rain, then Cave calling out like a wild prophet. ‘Looka yonder!’ Cave exhorts us, ‘A big black cloud come!/O comes to Tupelo’. A storm preceeds the birth of rock’s messiah, the birth that will bring into the world, through song, pockets of eternity. The supernatural aspects of this new king’s coming are accompanied not only by biblical rain but also a cessation of natural processes: hens can’t lay, cocks can’t crow, horses are freaked out, women and children have insomnia. Unlike the usual soft-focus sentimental myth of Elvis’s birth along with his dead twin in the shotgun shack in Tupelo, Cave includes a new character, the Sandman. Not the gentle fairy who sprinkled sand in children’s eyes so they can sleep but instead a version of E.T.A. Hoffmann’s Sandman, who throws sand into children’s eyes so that their eyes fall out and he can collect them to feed to his own children on the dark side of the moon.

It wasn’t Elvis, but one of Cave’s other idols who first initiated him into the extreme pleasures and darkness of rock. ‘I lost my innocence,’ Cave told an interviewer in the Guardian, ‘with Johnny Cash. I used to watch the Johnny Cash Show on television in Wangaratta when I was about 9 or 10 years old. At that stage I had really no idea about rock’n’roll. I watched him and from that point I saw that music could be an evil thing, a beautiful, evil thing’.

The ‘King’ in ‘Tupelo’, like Jesus, is born in a modest abode, on a concrete floor ‘with a bottle and a box and a cradle of straw’. The dead twin is placed ‘In a shoe-box tied with a ribbon of red’. Death and life are tied, like happiness and grief, beauty and ugliness are intertwined and can never separate. The song ends hinting at the weight that will haunt Elvis: ‘He carried the burden outa Tupelo.’ Not unlike Christ carrying the sins of the world.

What do we know of Elvis’s actual life in Tupelo? We know his mother Gladys had a difficult pregnancy and had to quit her job at the garment plant where she worked. We know that Elvis’s twin Jesse was born dead, but was never forgotten by either the Presley family or Elvis’s fans, Cave included. Gladys told Elvis: ‘When one twin dies the other got his strength.’

We know that even at age two, Elvis was drawn to music. At the Pentecostal church where his mother took him, Elvis regularly escaped from the pew and ran up to the choir, standing in front of them, eyes large with wonder, trying to sing along with the hymns. He got his guitar from the local hardware store at age eleven and in seventh grade started to take it to junior high, keeping it in his locker and playing for his friends at lunchtime and recess.

In Cave’s telling, Elvis’s birth is messianic and Elvis himself, who famously slept with a large statue of Christ on his bedside table, was drawn to Jesus. He was known to both acknowledge and deny his kinship to Christ. After a Las Vegas concert in 1972, a woman ran up to the stage carrying a crown on a red pillow, telling Elvis it was for him, because he was the king. Elvis smiled and took her hand, ‘Honey, I’m not the king. Christ is the king. I’m just a singer.’ Nearer the end of his life he told his spiritual adviser Larry Geller about a mystical experience he had in the desert. ‘I didn’t only see Jesus’s picture in the clouds–Jesus Christ literally exploded in me. Larry, it was me! I was Christ ...’

We also know that Elvis, from a young age, practised meditation. He told one of his early girlfriends, June, that if you look up at the moon and let yourself go totally relaxed and don’t think about anything else, just let yourself float in the space between the moon and the stars, that ‘If you relaxed enough ... you could get right there next to them.’ Elvis told June that he never spoke about this mystical experience because people think you are crazy ‘if they can’t understand you’.

‘There was a floating sense of inner harmony,’ Peter Guralnick writes in his biography of Elvis, ‘mixed with a ferocious hunger, a desperate striving linked to a pure outpouring of joy, that seemed to just tumble out of the music. It was the very attainment of art and passion, the natural beauty of the instinctive soul.’

‘I spend my days pushing Elvis Presley’s belly up a series of steep hills,’ writes Cave in The Sick Bag Song. And later: ‘I like the image of pushing Elvis Presley’s belly up a hill–the Sisyphean burden of our influences.’

In The Red Hand Files, the website where Cave answers questions posed by his fans, one asks ‘What does Elvis mean to you?’ In his reply, Cave focuses on Elvis as performer. ‘This narrative of suffering and rebirth is played out again and again within our own lives, but I believe it is captured most beautifully, within the musical performance itself.’ Cave points to the last ten minutes of the film This Is Elvis, in which the singer blunders the lyrics to ‘Are You Lonesome Tonight’. ‘It is one of the most traumatic pieces of footage I have ever seen.’ Afterwards Elvis, humiliated, bows his head, then his voice ‘steeped in sorrow’ begins ‘All My Trials’. As the concert ends the camera lingers on Elvis’s face: ‘tear-streaked... his head hung in sorrowful acceptance; and his caped arms outstretched in triumph. These are the stages of Christ’s passage upon the cross, the anguish, the sufferance and the resurrection.’

––

After moving to Memphis, Elvis attended both white and black gospel concerts with his parents. As a teenager he hung around Beale Street, mesmerised by the black singers. He also attended the Assembly of God church with his girlfriend Dixie Locke. The church started as a tent revival, then moved to a storefront and finally into a church building. Elvis told a reporter how the ‘holy rollers’ inspired him. ‘They would be jumping on the piano, moving every which way. The audience liked ’em. I guess I learned from those singers.’

Whenever a guest came to visit my daughter and me in Mississippi, we’d go see Al Green at his Full Gospel Tabernacle Church an hour away in Memphis. In the parking lot we always found the bass player’s van, covered with plastic rocket ships which hinted at his other gig in a funk band. One of my friends on hearing the music start up whispered into my ear, ‘My god, the dirty organ!’ It was not unusual for one of the Staple Singers to drop in, the choir backing her up. Every Sunday Al Green sang out from the pulpit. His youthful shining face sent me and the other members of the congregation into a euphoric trance. My daughter Abbie never got over those services. When we moved back to Brooklyn, where we sometimes attended the Episcopal church, she called the service ‘stupid’ and begged to be taken back to ‘real church’.

‘[Elvis] reminded me of the early days,’ DJ Tom Perryman said about seeing the singer perform, ‘of where I was raised in East Texas and going to these Holy Roller Brush Arbor meetings: seeing these people get religion.’

Acts 2:19: ‘Suddenly a sound came from heaven like a rush of a mighty wind and it filled all the house where they were sitting. And there appeared to them tongues of fire, distributed and resting on earth.’ These flames allowed Jesus’s traumatised disciples, just days after his crucifixion, to speak in languages that they did not know, languages that are both nonsensical and holy.

Rock’s debt to the blues tradition is well catalogued but the influence of the so called ‘holy rollers’ of the Pentecostal Church is either unacknowledged or minimised. Many of rock’s innovators, including Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Little Richard and James Brown, were raised in, and created by, the musical traditions of the southern Pentecostal Church.

After the service at Al Green’s church we’d visit Graceland. In Graceland, light seems to come at you from all directions, as if the sun has liquefied and flowed into the floor, walls and ceiling. I recognised in the glittery decor a longing for transcendence that is often labelled as tacky. The mirrored bar in the downstairs TV room was like a fenestral opening, the kind I spent most of my childhood searching for, that soft spot in reality that linked this world to the next. I liked the modest colonial kitchen. I could easily picture a bummed out and overweight Elvis wondering what it was all about as he raided the refrigerator. It’s this transfiguring light integrated with sadness that makes Graceland so powerful. Elvis’s endless hobbies–shooting guns, racquetball, horseback riding–all seemed like desperate attempts to fill up a faltering life.

Elvis is an icon, but not in any contemporary sense, not a one-dimensional computer icon. Neither is he an icon in the sense that Princess Di is an icon, someone who represented a particular kind of lifestyle. Elvis was an icon in the traditional sense of icons of the Greek Orthodox Church. These icons depict Christ, Mary or a saint shown against a gold background, which signified a source of illumination, independent of them. In iconography gold paint is built up from the base and the figure emerges from this globe of light. The gold light signified the mystical Other, the life force, a higher power, God.

‘As much as we twist and turn,’ Cave writes in The Sick Bag Song, ‘they [influences] are never really transcended. They are seared into our souls like a brand.’

III — OF WEAL AND WOE

Elvis’s story ends with sadness, loneliness and abandonment. He died ‘reading a book on the Shroud of Turin,’ writes David Rosen in the Tao of Elvis, ‘sitting on the American throne he fell forward, ending his life in a prayerful position on the thick bathroom carpet.’

‘The different kinds of vice,’ wrote Simone Weil, ‘the use of drugs, in the literal or metaphorical sense of the word, all such things institute the search for a state where beauty is tangible.’

In an interview in the 1980s Cave, clearly high, nods off. On his unrolled shirt sleeve, the interviewer sees specks of blood. Another journalist reports that at a Birthday Party show near the end of the band’s time together, Cave frequently falls down; bandmates kick him to get up. ‘Throughout the gig Cave looked like a corpse reanimated with a thousand-volt shock.’

Self-destruction, addiction, debasement, anorexia, even cutting, these are medical and psychological conditions but they are also spiritual. The fragile human sways under the weight of the world’s expectations, under the weight and responsibility of their own humanity. There is suffering and estrangement but also the possibility of opening up to grace.

‘Well,’ Dylan said, in 1991, as he accepted the Grammy for Lifetime Achievement, ‘my daddy, he didn’t leave me much, you know he was a very simple man, but what he did tell me was this, he did say, son, he said,’ there was nervous laughter from the audience, ‘he said, you know it’s possible to become so defiled in the world that your own father and mother will abandon you and if that happens, God will always believe in your ability to mend your ways.’

––

Cave, in The Red Hand Files, answers a question about evil. He believes ‘that we are spiritual and transcendent beings, that our lives have meaning, and that our individual actions have vast implications on the well-being of the universe’. What we do, how we act, affects not just those near us but the universe itself. ‘This acknowledgement of our capacity for evil, difficult as it may be, can ultimately become our redemption.’

Evil is just as human as empathy or love. While we try to cast evil as the other, evil is us. Evil is kin to debasement, but while debasement is a singular state, evil is an attempt to transfer our debasement and pain to another through violence.

‘The thief and the murderer,’ wrote T.H. Huxley, ‘follow nature just as much as the philanthropist.’

‘Song of Joy’ on the album Murder Ballads follows this equation of abasement forced onto another in the form of bloodshed. The speaker tells the story of meeting his wife Joy: ‘I had no idea what happiness a little love could bring’. But then he wakes one morning to his wife crying. She ‘became Joy in name only’. He is the father of the family, he and Joy have three daughters, and also the destroyer of the family. In acute detail he lays out how he found his wife bound with electrical tape, a gag in her mouth, stabbed and stuffed into a sleeping bag. His little girls are also dead. The song seems connected to the famous 1970 MacDonald murders in which a doctor killed and then denied killing his entire family. ‘I like the way the simple, almost naïve tradition of the murder ballad,’ Cave has said, ‘becomes a vehicle that can happily accommodate the most twisted acts of deranged machismo.’ ‘Song of Joy’ evokes in this listener Freud’s unheimlich, the uncanny or the unhomely. The horror concealed in the domestic has spurted out. The safe area of the home has been made unholy. Cave understands what the listener needs. That need is not always for beauty and love but sometimes for violence and blood. We are closer than we would like to admit to human predator and human prey. Horror, while rarely realised, is real. The Devil has won this particular round and Cave, rather than offering an unsatisfying redemption, keeps the story inside human misery and struggle. In ‘Song of Joy’ the listener serves the religious function of witness. The speaker is a monster, but we know that the Latin root of monster is reveal. The ‘monstrum’, writes professor of religion Timothy Beal, ‘is a message that breaks into this world from the realm of the divine.’

Johnny Cash, a singer with a powerful influence on Cave who also did a memorable cover of Cave’s ‘The Mercy Seat’, also depicted evil in his songs. In ‘Folsom Prison Blues’, the speaker is a murderer. ‘I shot a man in Reno just to see him die.’ Cash often said that while God was #1, the Devil was #2. ‘I learned not to laugh at the devil.’ As a boy Cash remembered walking in the woods and seeing a blazing fire in the distance between the tree trunks. ‘That must be the hell I’ve been hearing about.’ Cash saw his life as a battle. ‘I’m not obsessed with death,’ he wrote, ‘I’m obsessed with living. The battle against the dark one and the clinging to the right one is what my life is about.’

‘What is that sweet breath behind my ear, I hear you say?’ writes Cave in The Sick Bag Song. ‘It is the Muses and Johnny Cash blowing us along our way.’

‘To me,’ Cash wrote, ‘songs were the telephone to heaven and I tied up the line quite a bit.’ Many of Cash’s songs have the tension of the psalms, an older telephone to God. The psalms, particularly the lament psalms, vibrate with doubt, misery and passion. Cave admires how ‘verses of rapture, or ecstasy and love could hold within them apparently opposite sentiments–hate, revenge, bloody-mindedness–that were not mutually exclusive. This has left an enduring impression upon my songwriting.’ Cave’s chorus from ‘Mercy’ is psalm-like. ‘And I cried “Mercy”/Have mercy upon me/And I got down on my knees’. From Psalm 13: ‘How long wilt thou forget me O Lord? for ever? how long wilt thou hide thy face from me?’ Lines from ‘I Let Love In’–‘Lord, tell me what I done/ Please don’t leave me here on my own/Where are my friends?/My friends are gone’–parallel the sense of absence found in Psalm 74: ‘We see not our signs: there is no more any prophet: nether is there among us any that knoweth how long.’

Cave’s theology, like all true faith, is both fuelled by doubt and ever transforming. His songs, like psalms, are not nihilistic, but act as a counterweight to the wilful optimism of our culture, a culture that denies the darkness that we are all, in this life, called to face. In both Cave’s lyrics and the psalms, darkness is not easily transformed into light. No. Darkness is shared and solace is offered in fidelity, in a relentless solidarity. ‘Darkness,’ the theologian Walter Brueggemann has written, ‘is where new life is given.’

On stage Cave’s persona has been likened to a sinister old-time preacher. Critics early in his career questioned what one called his ‘deranged preacher shtick’. Many of his songs, like ‘City of Refuge’, have a camp meeting, revivalist energy. ‘In the days of madness/ My brother, my sister/When you’re dragged toward the Hell-mouth/You will beg for the end/But there ain’t gonna be one, friend/For the grave will spew you out/It will spew you out.’ Cave often gives what seems to be a sermon in the bridge of songs, but this, I would argue, is as it should be. Cave is not adding a mask, a shtick to the idea of the rock star; he is instead harkening back to the original Front Man, the preacher who fronted the choir.

Another religious archetype that Cave sometimes evokes is the circuit rider, a preacher dressed in black, on horseback with a Bible in his saddlebag. Circuit riders moved from revival to revival.

African American worshippers set up camp behind the raised platform and whites in front. Sunrise was welcomed by a trumpet call and preaching continued throughout the day. Many preachers, like Peter Akers, used their whole bodies as they spoke. Akers often fell to his knees (a knee drop!) and pressed his face in supplication to the platform.

Sinners who wanted to repent were welcomed to the front of the platform, a space known alternatively as the mercy seat, the mourner’s bench, the glory pen and the anxious seat. When enough mourners had come forward the preacher left the pulpit and moved into the pen where he continued to exhort, invite and counsel mourners. It’s hard not to think of rock performers, like Cave, playing to the first few rows of fans pressed up to the stage. Many of the mourners at camp meetings (and concerts) were women. Revivals were one of the few places antebellum women could act out. They cried, screamed, jerked and fell down. Redemption was cathartic, even sex-positive. One Alabama girl wrote in a letter to a friend that she had gained ‘many boyfriends’ at the camp meeting and that the girls had enjoyed themselves ‘more than ever before’. Peter Cartwright wrote in his memoir about the suddenness of female conversion, how bonnets and combs would fly and a young women’s hair ‘would crack almost as loud as a wagon whip’.

At night, thousands of lights filled the camp meeting grounds, bonfires, candles, flickering lamps attached to tree branches and fire altars, raised tripods blazing with enormous flames. The night revival is akin to the rock concert where lighters make stars in the dark. The concert is a secular happening, but also a holy one. Cave evokes in both song and performance what has been lost in religious practice, at least among his liberal, secular followers: the vastness of God, an otherworldly and theatrical grandeur.

‘I can remember the time when I used to sleep quietly without workings in my thoughts,’ writes Mary Rowlandson, who was captured by Native Americans in 1675, ‘but now it is other ways with me. When all are fast about me, and no eye open, but HIS who ever waketh, my thoughts are upon things past, upon the awful dispensation of the Lord towards us, upon HIS wonderful power and might ... I remember in the night season, how the other day I was in the midst of thousands of enemies, and nothing but death before me ... Oh! The wonderful power of God that mine eyes have seen, affording matter enough for my thoughts to run in, that when others are sleeping mine eyes are weeping.’

––

In 1998, Cave wrote an introduction to The Gospel According to Mark. In it he reflects on his evolving self and how this coincided with his discovery of the New Testament: ‘But you grow up. You do. You mellow out. Buds of compassion push through the cracks in the black and bitter soil. Your rage ceases to need a name. You no longer find comfort watching a whacked-out God tormenting a wretched humanity as you learn to forgive yourself and the world.’ Cave’s theology continues to morph. ‘Religions,’ philosopher John Gray writes, ‘seem substantial and enduring only because they are always invisibly changing.’

In the New Testament, Cave explained on the radio, ‘I slowly reacquainted myself with the Jesus of my childhood, that eerie figure that moves through the Gospels, the man of sorrows, and it was through him that I was given a chance to redefine my relationship with the world. The voice that spoke through me now was softer, sadder, more introspective.’

Who is Cave’s Jesus? He is first and foremost a storyteller, an artist even, a being whose imagination was both laser-like and unrestrained.

Jesus did not teach his followers a set of principles but showed them a way of life. Cave’s Jesus is not moralistic; instead he encourages a faith that is in close relation with a God who does not like complacency or stability, who is perpetually on the move, who pushes us on a journey with multiple ruptures and endless transformation.

‘As I understand it,’ wrote the songwriter Leonard Cohen, ‘into the heart of every Christian, Christ comes, and Christ goes. When, by his Grace, the landscape of the heart becomes vast and deep and limitless, then Christ makes His abode in the graceful heart and His Will prevails. The experience is recognized as Peace. In the absence of this experience much activity arises, divisions of every sort. Outside the organizational enterprise, which some applaud and some mistrust, stands the figure of Jesus, nailed to a human predicament, summoning the heart to comprehend its own suffering by dissolving itself in a radical confession of hospitality.’

‘Christ, it seemed to me,’ says Cave, ‘was the victim of humanistic lack of imagination, was hammered to the cross with the nails of creative vapidity.’

‘In his spiritual reality too,’ Josef Pieper writes in his book Only the Lover Sings, ‘man is constantly moving on–he is essentially becoming; he is on the way. For man to be means to be on the way–he cannot be in any other form, movement is intrinsic to a pilgrim, not yet arrived, regardless of whether he is aware of it or not, whether he accepts it or not.’

Song itself is a kind of movement, a becoming, a slice of eternity slipped into normal time to dilate and explode our fixedness. A song, like a book or a film, ‘must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us’.

In the last chapter of Varieties of Religious Experience, William James lays out the fundamental tenets that frame all faiths. 1: ‘There is something wrong about us as we naturally stand.’ 2: ‘We are saved from the wrongness by making proper connection with the higher powers.’ The conundrum that many of Cave’s songs explore is that divine connection, no matter how much we crave it, is often unstable, unbelievable, even inhuman. While God is not indifferent, he/she/they is hard to reach. A better strategy than forcing oneself up towards the Godhead is to connect with the divine in humans. ‘God don’t need me,’ a black minister says in Faulkner’s novel A Fable, ‘I bears witness to him of course, but my main witness is to man.’

In ‘The Witness Song’, Cave’s focus is human love. The speaker and his female partner both dip their hands into a fountain of healing water. Both claim to be healed, then admit that the holy water has not healed them. It’s as if the rebuking of God’s supernatural ability brings them closer together. What haunts the speaker as the song ends is not a Christian trope but the gesture the women makes as she leaves. ‘And she raised her hand up to her face/And brought it down again/I said “that gesture, it will haunt me”.’

The lover in ‘Do You Love Me?’ is a stand-in for the celestial sphere and all its creatures. ‘I found God and all His devils inside her/In my bed she cast the blizzard out/A mock sun blazed upon her head/ So completely filled with light she was.’ Cave searches for a faith that is not cookie-cutter or one size fits all, but deeply personal in its symbols, myths and theology. He pushes his own life through the Christian grid and usually finds his own life with all its uncertainty, rupture and sadness more real, if not completely satisfying.

In many songs Cave struggles toward a radical Christian theology that is on a human scale. The speaker in ‘Into My Arms’ does not believe in an interventionist God or angels, but human love. And in ‘Brompton Oratory’, the speaker tells us that the beauty of intimacy with his lover is almost impossible to endure, and in its sensations it rivals the foremost Christian ritual. ‘The blood imparted in little sips/The smell of you still on my hands/As I bring the cup up to my lips.’

There is no God without human beings; the human imagination makes God. Doubt in our imagined divinity is, in part, what fuels faith. ‘I have always found great motivating energy,’ Cave writes in The Red Hand Files, ‘in the idea that the thing I live my life yearning for, let’s call it God, in all probability does not exist ... my songs are conversations with the divine that might, in the end, be simply the babbling of a madman talking to himself.’

IV — ANGELOLOGY

Angels probably don’t exist either. These spiritual beings, according to the fifteenth-century philosopher Marsilio Ficino, are created when a person acts with a pureness of intent. Every angel is the embodiment of a single emotion or impulse. ‘The action transcends its physical place, time and individual connection and rises into the angel world: an angel is created.’

The single most vibrant dream of my life concerned angels. I was a new mother, at thirty-three, when I woke in the dark and went out into the hallway. On the landing I found a door that led to the fourth floor of my house. Why hadn’t I realised before that my house had four not three floors? I went up the stairs into a huge, high-ceilinged room, panelled with dark wood, and on the far wall was a three-storey fireplace, filled with enormous pink and orange flames. The fire warmed the room and was its only light source. Human creatures were lying and sitting on furs spread out on the floor; each one was speaking in a high-pitched melodic language I could not understand. They were speaking but their mouths did not move. They all had light brown skin, soft, shoulder-length hair and flat-chested, androgynous bodies. Each wore a beige bodysuit. While none of the creatures looked alike they all shared the same placid expression. The love between them was obvious in how they smiled at one another and lay with their heads in each other’s laps. It was not until I woke up that I realised they were angels.

What can be known about angels? I’m as valid an angelologist as anyone. From my dream I gather that angels have no specific sexual orientation and when they are not working as celestial messengers, they enjoy their downtime. In the Bible, angels are often fearsome. There is a reason that the first words they speak are ‘Be not afraid!’ In The Book of Judges, angels move up into heaven inside a column of fire. Gnostic texts claim that there are seventy-two angels, each responsible for the creation of a different part of the body. Angels existed long before Christianity, and Hippolytus wrote in 200 CE that the highest form of angels, prime angels, were born of a copulation between God and the Earth.

In And the Ass Saw the Angel, Euchrid sees his angel in the swamp. The ‘angel did ease herself into mah world’. First a whisper, then a flutter, then his name is called and finally the beating of silver wings. ‘Immersed in a cobalt light, she hovered before me. Her wings beat through mah lungs, fanning up nests and brittle shells and webs and shiny wings and little skeletons and skulls and skins around me.

And this visitation, she spoke sweetly to me. She did. “I love you, Euchrid,” she said. “Fear not, for I am delivered unto you as your keeper.”’

‘Angels,’ observes Michel de Certeau in his book White Ecstasy, ‘enter the human world as the cosmology that placed them in a celestial hierarchy begins to crumble.’ The less we believe in God, the more angels can escape heaven and walk with us on the earth.

The poet Rilke tells us that angels have ‘tired mouths’, and that they all resemble each other. Ficino explained that the sun is God and the stars, the angels. Also that while human souls are created daily, angels were all created before time began. Porphyry, around the third century CE, claimed you could attract an angel with an offering of ‘fruit and flowers’. Thomas Aquinas, known as the Angelic Doctor, said that each angel was a single species, a creature unto himself.

‘We are with you,’ the angels tell Cave in The Sick Bag Song, ‘but you must take the first step alone.’

‘Religion,’ John Gray writes in his book Seven Types of Atheism, ‘may involve the creation of illusions. But there is nothing in science that says illusion may not be useful, even indispensable, in life. The human mind is programmed for survival, not truth.’

In Cave’s mid-career songs angels are frightening and chaotic. In ‘The Hammer Song’, ‘an angel came/With many snakes in all his hands.’ The angels in ‘Straight to You’ are part of heaven’s chaos. ‘The saints are drunk and howling at the moon/The chariots of angels are colliding.’ As in many of Cave’s songs, while the spiritual world is vibrant and real, the speaker chooses human life, human fragility, human emotion. ‘I don’t believe in the existence of angels,’ Cave sings in ‘Into Your Arms’, perhaps his most theologically brilliant song, ‘but looking at you I wonder if that’s true.’

Maimonides, a Jewish philosopher born in 1135, extended the idea of the angel to include wind and fire. Also human passion: everyone who goes on a mission is an angel. The angel in this way of thinking is the imagination itself.

‘There is communion, there is language,’ Cave sets down, ‘there is God. God is a product of a creative imagination, and God is that imagination taken flight.’

‘Still,’ the poet Fanny Howe writes, ‘hope was like a throng of singers that circle the world both here and there having died and echoed over and over. What is a song but a call from the other side?’

In the song ‘Distant Sky’, from Skeleton Tree, Cave’s first album to come out after the death of his son Arthur in 2015, an angel speaks, an angel who will carry us back into God. ‘Let us go now, my one true love ... We can set out, we can set out for the distant skies/Watch the sun, watch it rising in your eyes ... Soon the children will be rising, will be rising/This is not for our eyes.’ Everything is one in the angel world. Time is not linear but simultaneous so the children both rise in the morning from their earthly beds as well as that final rising after death, the resurrection. As Rilke wrote, ‘Angels (they say) don’t know whether it is the living/they are moving among, or the dead.’

Before resurrection there is death and the angel of death comes as a messenger but also to coax the soul out of the body and into the open air. Gabriel will blast his trumpet to demarcate time’s ending. Graves will shiver and the reawakened bodies will push up like mushrooms from beneath their mouldy beds.

William Blake’s angel opens up metaphorical coffins, so the spiritually dead can run free. ‘And by came an Angel who had a bright key,/And he opened the coffins and set them all free.’ The Islamic angel Azrael was said to lure the soul by holding an apple from the tree of life to the nose of the dying person.

Libby, the wife of Bunny Munro in Cave’s second novel, The Death of Bunny Munro, is herself a kind of death angel. Returning to their flat having been with a prostitute, Bunny, who believes he is locked out of the marital bedroom, sees his wife through the keyhole, standing by the window wearing the orange nightgown that she wore on their wedding night. She floats in his mind in ‘dreamtime’, the ‘near-invisible’ material of her nightgown hanging from her nipples.

Once inside the bedroom, he finds his wife hanging from the security grille. ‘Her feet rest on the floor and her knees are buckled. She has used her own crouched weight to strangle herself.’

To Bunny Junior, their ten-year-old son, his mother is ever after a spirit. ‘A slowly dissolving ghost-lady, as incomplete as a hologram. He feels, in this instance, forever suspended on the swing, high in the air, never to descend, beyond human touch and con- sequence, motherless ...’

In Karl Ove Knausgaard’s novel A Time for Everything, angels are corporeal beings who, ever since Christ’s crucifixion, have been trapped on earth. They have thin wrists, claw-like fingers, deep eye sockets. They shake continuously and uncontrollably. They do not speak but shriek. As they move, they trail gaseous fire, like a comet.

The eighteenth-century mystic Emanuel Swedenborg often flew to heaven to converse with angels, though after these sessions he was never able to remember what the creatures told him. Humans have trouble both understanding and remembering angel speech. Angels may appear to speak but they are more likely communicating directly with their minds. ‘The angels,’ wrote Hildegard of Bingen, ‘who are spirits, cannot speak in a comprehensible language. Language is therefore a particular mission of humanity.’

In the 1987 film Wings of Desire, Nick Cave plays himself, a sort of anti-angel, all sharp skeletal angles in a blood-red shirt and black open vest. He is as agitated as the angels are peaceful, emoting as he sings ‘From Her to Eternity’ both desire and violence. He makes the angels feel human and the humans feel like angels.

The actual angels, Damiel and Cassiel, wear black trenchcoats and offer pastoral care to the people of Berlin. They see history from beginning to end; life is not linear but a continuous engagement with an ongoing present. In my favourite scene, Damiel, who will eventually choose the human over the angelic, soothes a dying man by moving his mind away from the pain caused by his motorcycle accident to the man’s treasured memories: ‘Albert Camus ... the swim in the waterfall ... first drops of rain ... bread and wine ... the veins of leaves, blowing grass, the colour of stones ... the dear one asleep in the next room ... the beautiful stranger.’

Angels, unlike humans, are not paradoxical. There is no difference between their inner and their outer. The scales are off their eyes and they see. While human subjectivity, blind spots, prejudices and ego all distort our vision, angels have no such blindness. I imagine their sight is how the visual artist Robert Irwin described the world just after he emerged from a sensory-deprivation tank. ‘For a few hours after you came out, you really did become more energy conscious, not just that leaves move, but that everything has a kind of aura, that nothing is wholly static, that color itself emanates a kind of energy. You noted each individual leaf, each individual tree. You picked up things which you normally blocked out.’

‘Is it you?’ Euchrid calls out at the end of And the Ass Saw the Angel, ‘Is it you, come to carry me through the gates?’

V — THE IN-BETWEEN

In his foreword to The Tibetan Book of the Dead, the Buddhist scholar Robert Thurman enjoins us to be prepared for the transition from corporeal to spirit. The point, he tells us, is to learn to love the clear light, not ‘shoot through the void and rise back up into an ... embodiment’. If we don’t learn to love the clear pre-dawn light we will end up inside either ‘lotus or womb or egg or moist cavity’ and the life cycle will start up once again.

One of the ways we can prepare, according to Thurman, is by being familiar with what heaven will look like. If we are Christian, we may see the Pearly Gates, if we’re Jewish we might see angels tending the garden of Eden, harvesting manna, otherwise known as angel food. If we are science fiction devotees we might find ourselves on another planet, pink waves crashing onto an indigo shore. If we are secular, Thurman advises that we read up on life-after-death experiences. ‘During the between-state,’ he instructs, ‘the consciousness is embodied in a ghost-like between body made of subtle energies structured by the imagery in the mind, similar to the subtle embodiment we experience in dreams.’

Raymond A. Moody collected near-death experiences in his book Life After Life. The steps are uncannily the same in every account: the person floats up out of their body; they see a bright light; out of the light comes a voice. After a car crash, a man watched people walk up to the wreck. ‘I would try to turn around, to get out of their way, but they would just walk through me.’

A woman felt a sort of drifting, she heard beautiful music and floated down the hallway onto her porch and right through the screen. Another saw a spirit that looked like ‘the clouds of cigarette smoke you can see when they are illuminated as they drift around a lamp’.

Since the death of his son, Cave has been in closer contact with his fans, staging so-called Conversations – events in which he answers random questions from the audience in between performing solo at the piano. He also answers fan questions on his website The Red Hand Files. In one question about the possibility of an afterlife, Cave writes how grief can engender the spirit world. ‘Within that whirling gyre all manner of madnesses exist; ghosts and spirits and dream visitations, and everything else that we, in our anguish, will into existence. These are precious gifts that are as valid and as real as we need them to be.’

‘Seeing the swallows flying through the summer air,’ Roland Barthes writes in his Mourning Diary, ‘I tell myself, thinking painfully of mama, how barbarous not to believe in souls, in the immortality of souls, the idiotic truth of materialism.’

There is an empty space within death culture and grief. We still haven’t articulated the spiritual components of grieving. I remember after my mother’s funeral how I felt at a complete loss on what to do next, how to console my flayed heart. Ghosteen, Cave’s latest album, is a valuable study of loss and sorrow, of the time after a loved one dies when we feel stuck with one foot in this world and one, with our beloved, in the next.

Angels are everywhere on Ghosteen, not named directly, but they sing on nearly every song with a wordless beauty and urgency that this listener finds both painful and lovely. Cave has said that Ghosteen is about a disembodied spirit. Sometimes the spirit speaks as in ‘Sun Forest’: ‘I am here/Beside you/Look for me/In the sun/I am beside you/I am within/In the sunshine/In the sun.’

On ‘Ghosteen Speaks’, ghost and human share not an earthly reality but a theology. ‘I try to forget/To remember/That nothing is something.’ The ancient idea that God is best found in the void. And the final incarnation, terrible but also full of grace: ‘I am within you/You are within me.’

––

As I finish this essay, I am at my desk in my attic office in Brooklyn. My window is not swarming with lady bugs. I look out not on moss-covered cedars but a brick wall and a plastic owl that sits on the ledge to scare away pigeons. I don’t watch, as I did in Mississippi, black-clad pilgrims head down the street to Rowan Oak. Though I do journey at my desk, my own sacred space, as passionately as any pilgrim. I see. I doubt. I wonder.

In Chekhov’s story ‘The Student’, a young seminarian walking home on a cold night comes across a group of peasant women standing around a large bonfire. It is a few days before Easter. The seminarian tells the story of Peter’s denial of Jesus, which brings the women to tears. As he leaves and continues walking home, he realises that it’s not his storytelling abilities but the old story itself that moved the women. This gives him a jolt, a sensation of eternity. ‘He even stopped for a minute to take breath. “The past,” he thought, “is linked with the present by an unbroken chain of events flowing one out of another.” And it seemed to him that he had just seen both ends of that chain; that when he touched one end the other quivered.’

Nick Cave’s work continues to do the implicit work of re-enchanting the world, of reminding us that our longing for God is real, though our main work is to witness, minister to and love one another. This is hard, particularly when we are called to love the dead. Cave’s call is to the imagination, to creativity, to the sound of the celestial spheres or what we call music. The balance of beauty and sorrow in his most recent songs reminds me of a saint’s reliquary I saw at the Metropolitan Museum, in a show featuring treasures of St Sophia: a small gold chapel made out of delicate filigree, inset with blue and red jewels. And at the bottom, in a sort of golden cage, lay items that at first shocked me with their incongruity: bone fragments and a swatch of rotten cloth. The fragile remnants of a saint, a holy animal, inside an eternal frame. This is our dilemma. We are God. We are human. Both at the same time. And this is what makes our position on earth tricky, humorous, beautiful and impossible.

Subscribe to Broadcast