Myth of the Genetic Blueprint

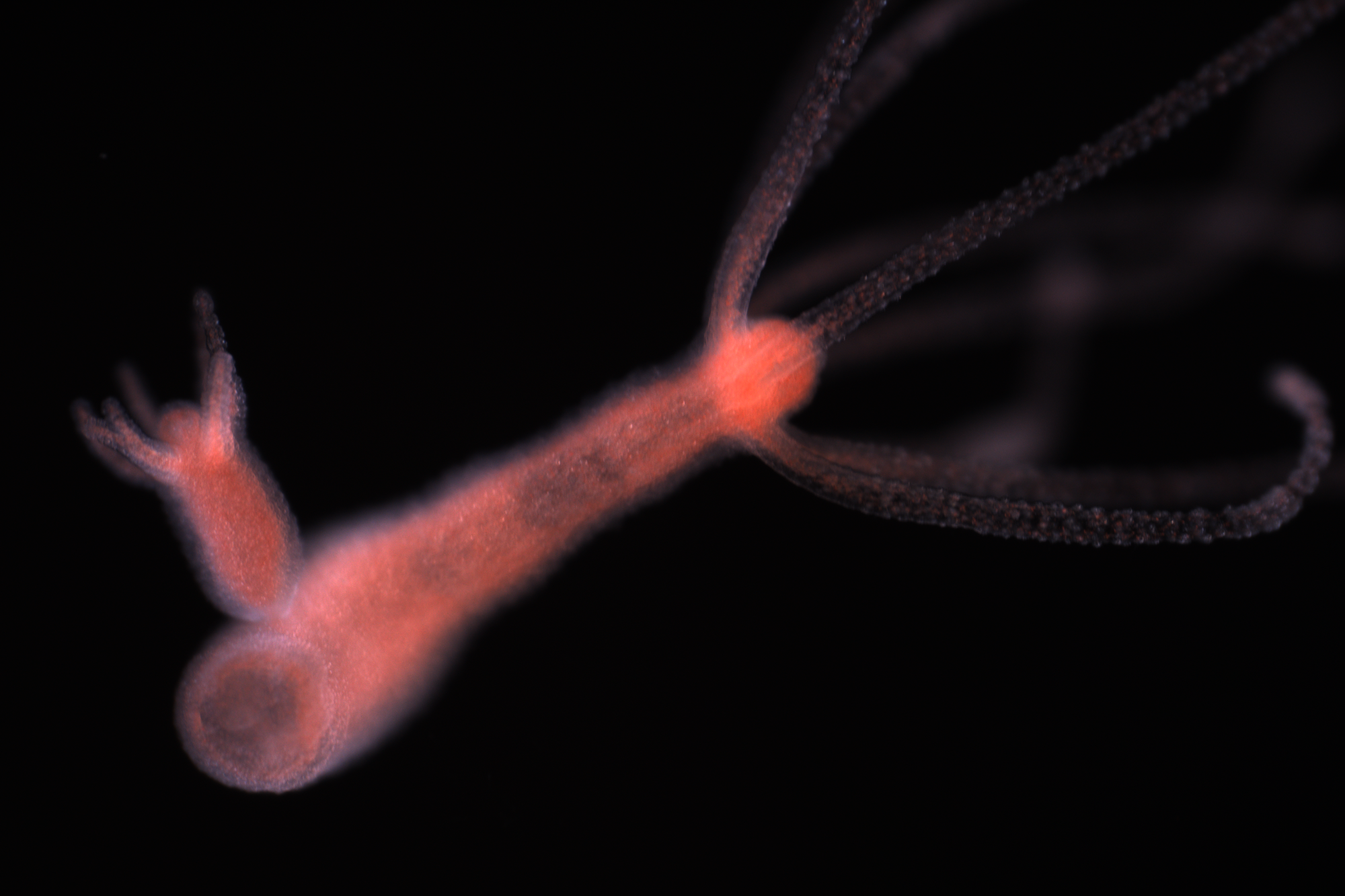

The head of an adult Hydra vulgaris in natural colors, imaged by a microscope equipped with a color camera. A ring of tentacles—which poison and catch prey—surrounds the mouth, which only opens when it feeds.

CC-BY Anaïs BaillesLike its mythological namesake, the real-life Hydra is hard to slay. These tiny animals, freshwater polyps related to jellyfish, can survive just about any encounter with a blade. Hack away one of its tentacles, and a Hydra will simply regrow the lost limb. Chop off a Hydra’s head or slice its cylindrical body in half, and within a few days you’ll have two new animals instead of one dead one.

Hydra can even regrow after being shredded to bits, centrifuged, and then smooshed back together into balls of a few hundred cells (they have no brains, so this probably isn’t as traumatic as it sounds). Each of those little balls—despite being, initially, a haphazard hodgepodge of random cells from the original, ill-fated animal—will grow into a perfectly functional Hydra. And if that weren’t enough, Hydra are so unfussy that they can even regrow from clumps of cells cobbled together from several different individuals. These patchwork aggregates develop into one new, united being—albeit one with a few extra heads.

“Most of the time I mix, like, 50 Hydra together,” physicist-turned-biologist Anaïs Bailles told me. “They don't care, they will actually make just one individual out of that.”

Bailles’ 50-animal aggregates derive from clonal strains that once shared the same genome. But Bailles has also mixed together two strains so different from one another that people used to think they were distinct species. Still, the animals grow perfectly well, "united again as one species," she says.

I've been thinking about Bailles' doubly mythological Hydra-Chimeras ever since talking to her about her work on Hydra development this summer. I had learned to think of biological development in machine terms, as construction according to a "genetic blueprint” or “genetic program." But faced with the Hydra, my machine metaphors failed: If a single animal can have several different genomes at once, which one is the blueprint? This might not even be the right question to ask. Because life is not constructed along pre-drawn plans. It grows.

Bailles isn’t shredding up Hydra for fun, though she does radiate with enthusiasm for these plucky polyps. At the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics in Dresden, Germany, Bailles studies Hydra to answer a question she originally encountered years ago as a young physicist pondering how the Big Bang spiraled outward into the universe we know today: How does complexity emerge in the natural world?

Two transgenic adult Hydra with their outer cell layer labeled with Green Fluorescent Protein, imaged by wide-field microscopy.

CC-BY Anaïs BaillesTwo transgenic adult Hydra, side by side. Their bodies have a tubular shape, with a sticky foot at one end and a head with tentacles on the other.

CC-BY Anaïs BaillesIn cosmology, this question is sometimes stated: “Why is there something rather than nothing?” The universe started out simple and became complex; scientists are still piecing together the story of how that happened. When Bailles first peered at a developing embryo under the microscope, she saw an echo of the same problem. Like the uncomplicated early universe that became our star-studded cosmos, an animal egg is far simpler than the organism it will become. Where does the complex form of the adult animal come from?

By the eighteenth century, some scientists had concluded that embryos must—somehow, somewhere—contain the full complexity of the future adult. Some imagined tiny homunculi crouching in the heads of sperm cells. Others didn’t take things quite so literally, but still believed that the embryo was, somehow, completely sculpted in advance by its parents. Growing up was simply a matter of scaling up.

This idea, called preformation, might seem unscientific to us now. But in its heyday, it was a materialist alternative to vitalism, the claim that physical forces alone could not account for life. Today, vitalism is considered magical thinking. But centuries ago, many scientists struggled to imagine that mere “matter in motion”—the only stuff of the universe, for a materialist—could organize spontaneously into a living being. Vitalists could invoke a supernatural “life force” that they believed guided the gradual emergence of new forms during development. Materialists could not. But if each new generation was entirely predetermined and engineered by the last, biological complexity would be no more mysterious than human construction. Placing parents in the role of clockmaker brought embryos into the clockwork universe—a perfect, predictable machine ruled not by the supernatural but by the laws of physics.

Now of course we know that it’s DNA, and not a preformed homunculus, that the sperm delivers to the egg. In the twentieth century, scientists identified the chromosomes as the units of inheritance. They “cracked the genetic code” by learning to read the protein messages written in DNA’s four-letter molecular alphabet—and much more. By the 1980s, scientists had counted the human chromosomes, linked sickle cell disease to a specific gene, cloned frogs, established the first genetic engineering company, and rebranded the leading embryology journal as one of developmental genetics. Researchers could now not only observe inheritance, but tinker with the “blueprint of life.”

And, very quickly, the genome was understood as just that—a blueprint. Writing in 1955, only three years after the discovery of the DNA double helix, physicist and biochemist George Gamow (who proposed the idea of the genetic code) described the cell as a factory and the chromosomes as the “filing cabinets where all the production plans and blueprints are stored.” The metaphor not only stuck, but shrunk: the genome metaphorically transformed from a filing cabinet of blueprints into the blueprint, singular. When the Human Genome Project completed the first full human genome sequence in 2000, President Bill Clinton described it in a White House announcement as the “working blueprint of the human race.” A quarter century later, in 2023, the announcement of the first human pangenome (a sort of collective genome accommodating human diversity) was announced as an “expanding view of humanity’s DNA blueprint.”

The blueprint is an intuitive metaphor, but Bailles and her Hydra should give us pause. When she shreds up and recombines multiple animals in a Hydra-Chimera, different patches of tissue could easily harbor distinct genomes. And yet, together, those cells become one animal. Where is its blueprint?

You can find it clutched in the tiny fist of the sperm homunculus: in other words, nowhere. The idea of the genetic blueprint is “a sort of neo-preformation,” neurogeneticist Kevin Mitchell of Ireland's Trinity College Dublin told me. Nobody is arguing anymore that dogs have puppies instead of kittens because dog embryos contain tiny, preformed dogs, Mitchell says. Nevertheless, the blueprint metaphor still asserts that, in its place, “there is a dog genome, which contains—in an inescapable, deterministic way—the outcome of development.”

Bailles studies brainless polyps; Mitchell studies brains. Specifically, he’s interested in the genetics of brain development, especially as it relates to psychiatric and neurological disorders and differences. And yet he’ll be the first to say that there is no genetic blueprint for a brain.

“The term blueprint is problematic because it suggests that one bit of the genome encodes one bit of the organism, right? There's a one-to-one mapping. You can already see in the genome the shape of the thing to come,” Mitchell explained. In a blueprint, windows stand for windows and staircases stand for staircases. But if you crack open a genome, you will not find anything that corresponds so directly and specifically to an eye, an optic nerve, or sickle-cell anemia. Genes specify the amino acid sequences of proteins, not fully formed body parts or behaviors or diseases.

Simon Fisher at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in the Netherlands also criticized the idea of one-to-one mapping when I asked him about his problems with the genomic blueprint metaphor, which he’s vocal about on social media. Fisher studies the role of genes in language and language disorders and was on the team that, in 2001, discovered the first gene mutation associated with developmental speech and language disorders.

“When I started working on this—on genes and language and genes and language disorders—there were people looking for a gene for grammar,” Fisher told me. “They really thought there was going to be one gene that would do an operation in the brain that would explain all of language. And there are still people who believe that.”

The gene Fisher and his colleagues linked to language, FOXP2, is associated with the development of speech in people. In birds, it is involved in learning vocalizations and songs. In bats, it might play a role in echolocation. When FOXP2 doesn’t work normally, it can cause speech disorders in humans and disturb singing in birds. “It’s very easy to break a behavior by breaking a gene, right? But for it to encode this whole behavior?” Fisher said. “That's a stretch.”

What FOXP2 does encode is a protein. Trios of DNA “letters” correspond to specific amino acids, the building blocks of protein, and when a gene is expressed, its DNA is “read off” in a chain of biochemical steps to build a protein. FOXP2’s protein then sticks to specific sequences of DNA to change how other genes are read off into their own corresponding proteins. Researchers still haven’t found all of its target genes, but there are likely hundreds. What’s clear is that FOXP2 is far more than a “language gene”—mutant mice without it are runts with deformed brains and lungs so weak that most can’t survive longer than a month. It also plays roles in other organs and might not work normally in some cancers.

Even in simpler cases, like the single-gene mutations that cause cystic fibrosis, the gene involved does not “code for” cystic fibrosis, Fisher explained. It codes for a protein that, when damaged or absent, leads to disease in the context of a body.

But if the genome does not contain a clear plan for an adult organism, what does it encode?

In the 1961, biologists François Jacob and Jacques Monod described a genetic circuit that switches a gene for lactase, the lactose-digesting enzyme, on or off in bacteria. Glucose is the bacteria’s favorite food, but it’ll make do with lactose in a pinch. The circuit Jacob and Monod discovered, the lac operon, “turns on” lactase only when lactose is available and there’s no glucose around. This discovery won the Nobel Prize in 1965 and inspired Monod to imagine the genome not as a blueprint, but as a program or computer code.

This metaphor is perhaps more helpful because it acknowledges that development plays out in time: the genome, according to Monod, is a set of step-by-step instructions for building an organism, not a blueprint of the final product.

FOXP2 doesn’t map to any one behavior or structure but rather controls how other genes behave, like a logical operation in a computer program. But there's a problem with the program metaphor. Run a program twice, and it should do exactly the same thing, yielding reliable, reproducible results. Real genomes, however, do not work that way. Environmental factors—for instance, prenatal exposure to alcohol—can clearly influence development in ways that are not preprogrammed in the genome. But even if the influence of nurture could be eliminated completely, nature would still not get the same result from every run of its genetic “programs.”

Mitchell believes that development involves a degree of random chance—what he calls “developmental noise.” In normal flies, for example, particular neurons involved in muscle activation almost always connect to the same muscles in the body wall. But Mitchell has shown that mutating a particular gene leads those neurons to fail to connect, but not always — only sometimes. The mutation doesn't guarantee any particular outcome, it just skews the odds.

Recognizing inherent developmental noise could help resolve some of the confusion around why traits like height, left-handedness, or—more importantly—autism are highly but not entirely heritable. When one identical twin is autistic, the other is autistic up to around 90 percent of the time. 90 percent sounds high. But it isn't 100 percent.

“Evolution has made this really robust program,” says Mitchell. “But when you start to degrade that program by adding genetic variation, it just becomes a bit more variable.”

This is just one of many reasons some researchers think we need completely new ways of thinking about genes and development. Alan Rodrigues and Amy Shyer of Rockefeller University, both life scientists studying how organs self-organize in embryos, the genome is neither a blueprint nor a code. It’s not a machine at all, they told me, and thinking of life that way is holding science back.

Putting on the shoes of a twentieth-century scientist, it’s easy to understand why researchers looked to machines to understand life. The long effort to purge biology of vitalism and bring it closer to the domain of physical science and its “mechanisms” had been hard fought and only recently won. Industrialization had, over the preceding century, mechanized the world—and thanks to Alan Turing’s theory of computation, that even included human thought. The first commercial digital computer, a room-sized machine called UNIVAC I, was turned on at the U.S. Census Bureau two years before the double helix structure was discovered in 1953. The new sciences of machine code and genetic code matured in parallel.

So it’s perhaps understandable that genetics and developmental biology have long focused “on information transmission, linear causality, chains of cause and effect, and things like regulation and control,” Rodrigues told me. “I’m willing to admit that this was a useful way to get a grounding in biology over the last 50 years. But our view is that it is now a bottleneck and we need to let go of the machine.”

Shyer and Rodrigues are especially interested in how life self-organizes across scales in space and time. They are skeptical that genes and biomolecules are more fundamental than processes unfolding at the scale of tissues, organs or organisms. Two years ago, they showed that skin follicles in chick embryos are not pre-patterned by genes or proteins, but emerge dynamically out of physical interactions between clumps of stiffer or more fluid cells at the level of tissue. It’s not just gene expression that influences groups of cells, they argue. Mechanical properties that only exist at the group level—like stiffness or fluidity—can ripple downward to influence gene expression.

Bailles, Mitchell, Fisher, Rodrigues, and Shyer work on very different systems and come from very different disciplinary backgrounds. But their work echoes a common message: that the complexity of life is not pre-encoded in the genome, but emerges through development in a way that is not fully captured by the mechanical metaphors of blueprints and computer codes.

A budding adult Hydra vulgaris in natural colors, imaged by a microscope equipped with a color camera. The animal reproduces asexually by forming a small clone on its side, which detaches once it reaches sufficient size.

CC-BY Anaïs BaillesWhen I asked Fisher, Rodrigues, and Shyer about better metaphors, they said that they don’t have a ready replacement—though Shyer and Rodrigues are actively working with philosophers to develop new and better ways of thinking and talking about life. Mitchell, though, does have a concrete suggestion. Recently, he and a colleague proposed that the genome is like a generative model, the kind of computer program that powers AI art generators like Midjourney. Generative models learn abstract patterns—“catness” instead of a specific cat—and elaborate them dynamically in several increasingly complex, partially randomized steps to produce entirely new images. The same model, given the same prompt, is exceedingly unlikely to produce the same output twice.

Mitchell’s metaphor seems particularly helpful for understanding the role of chance in development and for recruiting machine mathematics to describe life in useful ways. Still, I can’t help but yearn for a more organic analogy. Generative models are, after all, machines. And life—a shifting, restless thing that's more process than artifact—is not.

In their 1980 book Metaphors We Live By, George Lakoff and Mark Johnson hypothesized that human language—and cognition—rests on metaphors rooted in our embodied, biological lives. Perhaps it’s a bit ironic, then, that I find myself leaning more and more on language itself as a metaphor to understand biology.

Life is not a sermon “read out” from some genetic Book of Genesis. Development, I imagine, is a dialogue between the genome, experience, environment, chance, and the forces of the physical world. And just like human conversation, it unfolds simultaneously across scales in space and time—a shared glance, a quick text, a dinner conversation, a public debate, a viral video, a protest, a movement. Each scale feeds into the next, tied up in tangled loops of cause and effect like the infinite staircases of an M.C. Escher painting. But even that impossible blueprint would be just a beginning. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast