Walker in the City

“Walking is, after all, interrupted falling.” So wrote Garnette Cadogan of the activity that’s become his salvation and his credo. For this urban essayist extraordinaire, walking the city’s streets is much more than putting one foot in front of the other. It is the means by which “we see, we listen, we speak, and we trust that each step we take won’t be our last, but will lead us into a deeper understanding of the self and others.”

Those lines appeared in Cadogan’s landmark essay on "Walking While Black," which struck a deeply resonant chord during the #BLM uprisings of a few years back—and evince a larger body of work that’s roved, with curiosity and care, across a wide range of fields. At Pioneer Works, Cadogan has helped lead workshops on mapping and psychogeography. Nowadays, he’s a distinguished lecturer in Architecture and Urban Planning at MIT. But he returned to Red Hook, one Sunday this spring, to talk with me about urban justice, flâneurie, and “walking into our best thoughts.”

You grew up in Kingston, Jamaica, and are now a New Yorker. You’ve written about cities all over the world. But when and where did you come to walking as an ideal way of doing so—as an urban activity, and a subject, that you could write about in a fruitful way?

I have John Freeman, the editor, to thank for that. John—who edited Granta and Freeman's and is now at Knopf—had invited me to contribute to a volume called Tales of Two Cities, which looked at inequality here in New York City. I was wrestling with the essay I wanted to write for that collection, and as is my habit when I'm stuck in thought, I decided to walk. There’s a quote from Kierkegaard where he speaks about walking to your better thoughts, your better self. And as I was walking, trying to work through the thoughts, trying to figure out how to dive into something as huge and seemingly unmanageable as the subject of inequality in New York, walking itself started to impress itself upon me as a way of thinking this through. My friend Suketu Mehta, one of our great writers on cities, said, "Well, why not just write an essay about walking? You have a habit of walking from the Upper East Side to Hunts Point [in the South Bronx], of walking from what is often classified as the wealthiest neighborhood in New York City to the poorest district in New York City, why not share that with readers?"

It impressed upon me just how much could be told through walking because of the nature of walking—it's a way of observing the world and interacting with the world and understanding the world.

Experiencing it at a human pace.

Exactly. And what does it mean to move through the world at a human pace? How does it help us understand its contrast and varieties? Its sensory richness, sights, sounds, smells, tastes, feelings? I began thinking: why not look to see what else might come from looking at the world, not merely at a human pace, but also at a human scale? Instead of zooming out to understand, walking allows us to come close, but also to leave ourselves open to improvisation, to serendipity, to surprise.

Your marvelous essays on walking, which are now taught at schools all over the country, are born of the places you’ve walked—Kingston, New Orleans, New York. But they’re also born of your reading; your work is hugely erudite. I wonder if you could just talk about some other writers—we just mentioned Kierkegaard—who have mattered to you. Perhaps we could begin with the French guys: Baudelaire and Balzac. People say, thinking of how your writing on walking the city may echo Baudelaire, that you’re a flâneur. And you reject that. Tell us why.

I argue with the flâneur because he is a figure that feels too aloof. Also, the flâneur is in some ways trying to make sense of himself more than the people before him. People might think that's unfair, but you read the writing of the flâneurs, and they're walking around the city, looking around, observing it—it’s too much aloof distance, too connoisseur-like, rather than somebody who's plugged into the rhythm of the city itself. They're looking at the city often to try to work through their own thinking about themselves. And yes, it's important to insist on the necessity of understanding ourselves through understanding others. But much of the writing [in this tradition] feels less like self-examination and more like self-projection.

Or self-realization. And there's a certain privilege in that—it's not by accident that these are white men of a certain position. The essay of yours that has traveled most widely is titled “Black and Blue,” but went viral on the internet under the name “Walking While Black.” That essay is an incredibly rich meditation on what it is to move through space in a particular body—in your case, in the body of a black man.

And you write about the way you, as a person so well versed in this literature of walking, and who shares the same affections for the city voiced by these other writers, have often been prevented from having some of the experiences they write about. In Jamaica, where you grew up, walking was a necessity for you, in certain ways. But in New Orleans, where you went to college and lived for years, walking switched to your being perceived on the street as a threat—it became a curtailment of possibility instead of opening things up. And you've written beautifully about the ways in which, in New York, walking has meant being perceived as a threat, yes, but also about how it has been solace for you; it's been emancipation, if I might use that word. It's something that's been hugely important to your experience of the city and yourself as a thinker and a person.

Yes, and that latter sense explains part of my fight with the idea of flâneurie—the detachment that is assumed in standing apart from something and observing it, in investigating it rather than finding ways to be a part of it. What walking does is it inscribes a place onto you, but it does that by having you inscribe yourself onto it.

In his journals, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote about how "the ground is all memoranda and signatures.” Your steps, in this sense, are signatures: as we walk, our footsteps leave a part of us behind. Even if someone is not able to walk, they’re still moving through at that human pace, [whether by way of] a wheelchair or piggyback ride if you're a child that's not able to walk yet.

So to walk is to form memories. It's a deeply memorial act of leaving marks of yourself in a place, and also of opening yourself up to having a place leave its marks on you. To go from place to place, city to city, is to participate in this rich acts of memory making and meaning making. And you begin to understand different cities, you begin to understand different places and understand more and more what it means to take them on their own terms. And you make meaning as you're making memories; you become a part of a place as it becomes a part of you.

That’s beautifully put, and I've been so fascinated by the ways in which your work has resonated for people in different ways. As a society, we're having urgent conversations about race and public space and systemic violence. But your work has also really resonated with thinkers and writers who have written and thought deeply about moving through space in other ways—about what “the right to the city” looks like for a woman, say, or for someone who is inhabiting a different body. And I think, for example, of our friend and collaborator, Rebecca Solnit, who has written powerfully and eloquently about the desire and right to move through the city without being harassed or threatened. I wonder if you could tell us a bit about the conversations that your work has enabled.

One of the things that Rebecca has been thinking and writing about, and which we’ve had rich discussions about, is public space as common space: a common ground, where we encounter and form friendships, coalitions, have debates, play together, fight together, think together, laugh and love together. But this public space is also a contested space. I think of my friend Lauren Elkin, who wrote the book Flâneuse, and demonstrated a long tradition of women walking and contributing richly to public spaces, which is something you might never guess based on the way we name streets and squares and parks and monuments—you know, as if only men have ever made contributions to public life and public space. But it's contested space. So to think about walking is to think about life in the street, life in public, and about what it actually means to have an open city, a pluralistic city, a place in which we can coexist.

One way to distill that set of questions is this phrase that many geographers are fond of: “the right to the city,” coined by David Harvey. This idea of who has the right to the city—not merely in terms of who has the right to be here, but to walk the streets or walk safely—is really resonant. Writers like Rebecca and Lauren have pointed out that, historically, in many cities and countries around the world, it has been literally illegal or at least deeply discouraged for women to walk outside unaccompanied, until not that long ago. But the point about the right to the city is that it's not just about who has the right to be in space, but who has the right to shape the future of the city and to imagine possibilities and to take part in public life.

Right, which makes me think of the marvelous work of Emily Raboteau, who's asked time and again, what kind of city do we want, and who has the right to the city? The right to a healthy city, a safer city, a more equitable city, a more joyous city. Emily has written about this beautifully from essays about the climate crisis to writings about playgrounds, or photography.

I think too of [James] Baldwin, who wrote about what it means to move through public spaces with a dark body. I could mention so many other people, Vivian Gornick and others. There's an emphasis, with these writers, on the joyousness, the beauty, the surprise, the playfulness, the contemplation that can come from walking in the city.

You’re best known as a writer, but you don't teach in a writing program. You're at MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning, working with people who think about how we actually design cities, and how we use them. What’s that been like?

Architecture, urban planning, and urban studies are all future-looking disciplines and practices. That means trying to come to terms with the world as it is, but then asking, are there ways to shape it so that we have a better existence as a collective—as people who are obligated to each other, as fellow citizens—while also thinking about non-human life? In other words, thinking deeply about stewardship—what do we owe each other, to what do we owe the earth, and how can we look to the future and make plans to move carefully, thoughtfully, and caringly towards a better future. Whether it be housing or economic development or community development and engagement or climate change or city design or energy policies, building, playgrounds or memorials—these are all ways of imagining the future, of thinking about our obligations and responsibilities, and not merely our rights. Emily Raboteau once said to me, how might we be better ancestors?

Beautiful. You teach a course now at MIT called “The City At Night.” Is this true?

Yes. Actually, the title is “Werewolves, Wanderers, and Laborers: The City at Night,” because I wanted to [consider] how we think about those who are pushed to the margins, and our obligations and responsibilities to them. How do we think about people who live transiently, whether because of poverty or inequality or environmental or economic injustice? The unhoused, the newcomer, the migrant, the undocumented, the person who's moved from country to city with dreams and hopes and trying to make a living. And how does night heighten the issue?

What does it mean to actually plan and design for the city at night? How do we think about zoning and regulations and housing and social services? About the people who we call essential workers but treat as anything but? When we think of the night, how do we think about transportation and infrastructure? How do we design for somebody who's injured or somebody who's disabled or, feel vulnerable, in other ways?

Being “street-smart” for example, is not merely about calibrating your fears to the world around you. If you are dark in complexion, you have to calibrate your fears to other people's fears. How does the night bring all of this to the fore? And how do we begin to wrestle with these things as we're thinking about the cities that we want and the cities that we're trying to create—better cities and a better urban life? The night is a place of mystery but also a place of regulation, and sometimes overregulation.

And you, Garnette, would know that well—I’m reminded of the essay you wrote for me, a few years ago, about taking a 24-hour walk around the city. It was your idea—I didn't coerce you. [Laughs.]

I loved that.

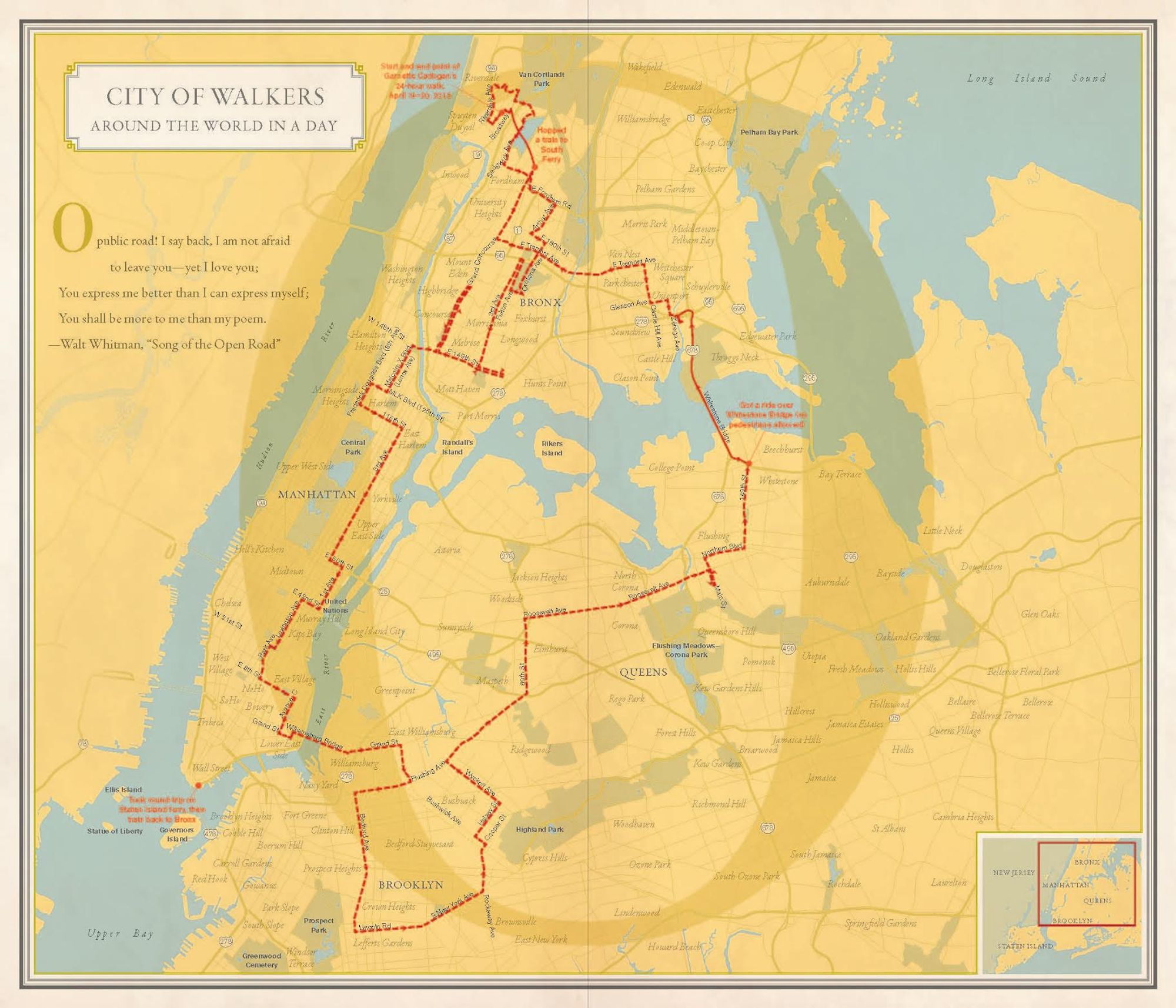

This is an essay that appears in Nonstop Metropolis, the atlas of New York which I created with Rebecca Solnit and for which you served as our editor-at-large. For that piece, which we called “Round and Round,” you started off from your home in the Bronx and took this huge circle through all five boroughs of the city, ending up back in the Bronx after traversing Manhattan and Brooklyn and Queens. You even took the ferry to Staten Island. And that essay is, among other things, a wonderful ode to the joy that's to be found in encounter and in serendipity, and in the ways a city works for those who inhabit it and have love for it, and what it can offer up, especially perhaps at 3 am.

Yes. Part of it came from us thinking about what it means to actually understand the immigrant city: how do newcomers—those who have just landed, but also people who've been around for a while and are made to feel like they're newcomers—how do they understand and interpret the city? How do they make themselves at home in the city, and what can we learn from them? What does it mean to see the city as a newcomer, with those senses of expectancy and oddness and enthusiasm, trepidation, some fear? And, seeing through the eyes of the newcomer, how might we understand something about the city but also about ourselves—how might we begin to adjust our own thinking about what it means to be at home in a place?

And again, what better way to explore these things than to move through the city at human scale and human pace, to walk through all five boroughs and to see it in all its contrast and rich variety, but also in its mysteriousness. There’s a beautiful not knowing in the humility of the observer.

That reminds me of the opening of the essay, which finds you getting off the subway in South Williamsburg. You're walking down the street, It's getting near dusk on a Friday evening and this figure runs towards you. It's an Orthodox Jewish man. A Hasidic fellow in his black coat and hat runs up to you, and you feel instinctively, oh, is this a threat? But this guy gets right up in your face, pauses, and says, “Do you want to do a good deed?”

A lovely man.

And he invites you to change the light bulb for his family—it's the Sabbath. And it's a wonderful way into this essay that is about the wonders of inhabiting public space and being open to encounter, because we often move through the world not terribly open to encounter. New Yorkers are incredibly expert at not making eye contact—and there's a reason for that. We all have to get through the day.

Yes, but it’s so important to ask, what do we lose when we organize our steps according to fear? I don't want to suggest to people not to be street-wise, not to calibrate their movements or encounters, but I also want to insist on openness, to say that we do lose a lot if we shape our embraces or rejections of the world according to our fear.

One of the misunderstandings of my work on walking is the sense that it’s about how awful it is to be Black in America. And that's not what I'm saying at all. Matter of fact, I think there's so much that's glorious and joyous and beautiful and terrific and funny and delightful and moving about being Black in America. The essay [“Black and Blue”] is not saying that the sum total of our existence is tragedy, far from it. It's lamenting what actually happens to us, and to those who are afraid of me, when fear guides our experience or understanding.

Campaigns for political office often lean into that fear, into questions of “safety.” It's expedient for them to play up our fears and to present themselves as the ones who are coming in to bring safety and peace. I'm always suspicious of political candidates because, apart from being devilishly opportunistic, they're always telling us that we ought to be viewing our cities, our neighborhoods, and our fellow humans as things to be feared, suspicious of, wary of. They're actually encouraging us to move through the world not with that openness, that rich expectation of encounter, but with fear.

The kind of leadership we need and should demand is one that cultivates a civic attachment and civic health. So part of what that essay was getting at is a caution about fear, about how fear degrades and dehumanizes us in so many ways. And when fear is the vector by which we move through the world, it diminishes us.

Which is part of why, as I’ve heard you say, we need more places and institutions in the city that feel permeable and open—places, perhaps, like Pioneer Works, here in Red Hook, Brooklyn. A cultural institution, we hope, that always feels cared for, that feels curated, but that also allows people to enter and to take part.

Permeability is so important because it's what lets us think of New York as an open city. Spaces that are permeable allow that rich encounter in which fear is not the guiding force for interactions. They also acknowledge something which is really crucial in the cities that thrive the most: cities we feel have some commitment to us and care for us are ones we can see ourselves shaping as they shape us.

I spoke earlier about Emerson, about his idea of making a signature on the ground, literally and metaphorically. That happening involves both top-down and bottom-up processes, working together to continuously shape and reshape the city, as we are also being shaped and reshaped. It means creating the kind of civic structures and arrangements in which people begin to see themselves in others. The city at its best is a place of recognition and acknowledgement, where we both recognize others in us and ourselves in others. It affords us this greater imagination where together we can think of a true “us,” a true “we.” ♦

This conversation aired on April 9th, 2023, during the Second Sundays Broadcast Live Hour on 8 Ball Radio. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Subscribe to Broadcast