Futility of Effort: Alice Neel and Motherhood, 1930–46

In the 1980s, my grandmother lived a few hours south of my mother and me in a small, sleepy town near the Gulf of Mexico: Punta Gorda, Florida. Aside from strong memories of the dramatic weather in this little fishing village, what I recall most from my time at her house is that sometimes she’d let me stay up late with her and watch The Tonight Show. I remember the way she’d be propped up in bed with curlers in her hair; the faint smell of mildew that plagues most homes in Florida, always lingering in the nightly air; and how much she enjoyed the show, despite dozing off somewhere in the middle of it. It was one of her programs, among many.

On February 21, 1984, the artist Alice Neel, then eighty-four years old, was a guest on Tonight. Neel was sick but you’d never know it—only months later, on October 13, she passed away after a long battle with colon cancer. The lively banter and vivacious wit she brought to the show was all the more astonishing given her illness. Something of that endearing persistence is there throughout all of her paintings, too.

Born in 1900 in another small town, this one outside Philadelphia, Neel possessed an empirical knowledge of the fine line between laughing and crying: So many of her jokes with Johnny Carson that night were both funny and sad. Looking to the audience, she proclaimed that backstage Carson had offered to marry her: “He said, ‘There’s still hope for you!’" I’m sure my grandmother adored this—she loved to talk about how much she learned from Carson’s “unusual” guests, particularly artists and writers. Neel’s humor had a pragmatism to it, just like her politics, and elements of both are evident in her expressionist and social realist paintings. Neel never clung to one particular movement or “-ism,” however: She continuously modified the look of her work, not to fit an era’s style but to suit only herself.

Neel had four children with three different men, and, after one marriage (with the Cuban artist Carlos Enríquez Gómez) quickly fell apart, she never married again, although she had several long-term partners and live-in companions, who stayed with her on and off in East Harlem for nearly forty years. These men were never as fascinating as her; she tended to take in “second-rate artists and first-rate cads,” as Deborah Solomon put This essay, which I began in 2017 and left to linger as a draft until seeing the hit Neel retrospective, People Come First, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in May 2021, explores the breadth of these vicissitudes. I began writing it because I have long been drawn to Neel’s uncensored candor for representing the physical and psychic challenges of all stages of motherhood. I wanted to understand how her living arrangements and life as a single mother affected her work, and how her children’s upbringing was deeply impacted by the various people Neel brought home, the company she kept. And it seems she always had company—even the family’s housekeeper and her child lived with the Neels for some time.

The children Neel lost may have dissuaded her from marrying again, and cemented her resolve to be truly independent. Her first daughter with Enríquez, Santillana, was born on December 26, 1926, in Havana, and died in New York shortly before her first birthday of diphtheria. A glum and minimal (for Neel) canvas in the Met’s retrospective, Futility of Effort (1930), was made in response to Santillana’s passing and, as the work bleakly shows, the death of another infant who had choked, not long after, between the bars of its crib. Neel described this work as one of her most “revolutionary” paintings, perhaps for its fraught psychological elements—a strong theme in her later work—and its decentralized composition.

Her second child with Enríquez, nicknamed Isabetta by Neel (her full name was Isabella Lillian Enríquez), was born November 24, 1928, in New York. In the spring of 1930 Enríquez took the toddler to Havana in what would now be considered a kidnapping. Isabetta remained in Cuba throughout her youth, having little contact with her mother while being raised by Enríquez’s well-off family. Eventually Neel and Isabetta became estranged from each other—Isabetta occasionally tried to engage with her mother, but Neel was often non-responsive. Neel never officially divorced Enríquez, but they separated in 1930 and she subsequently suffered a nervous breakdown and tried to commit suicide (she attempted this more than once). She never tried to bring her daughter back to the US. Isabetta died of suicide in 1982 at age fifty-four; Neel hadn’t seen her in over thirty years.

Neel’s painting Degenerate Madonna, from 1930, a horrifying image of early motherhood, is likely a psychological self-portrait. Novelist Claire Messud has adeptly described the work: “A mother, notable chiefly for the ghostly black nimbus of her hair, a mouth like a gash, and fierce elongated nipples like bloody daggers, overlooks a ghastly-grey bald infant with a skull of hydrocephalic proportions, tiny, crooked features and stiff white legs like a doll’s; while the faint profile of a second bald-headed child—or the infant’s reflection—looms bodiless in the Like so much of Neel’s work, what underpins this painting is not cruelty or even love, but the sense that these beings, despite their dilapidated appearance, still have a sense of dignity. As Neel once told her friend Mike Gold, a writer for the Daily Worker, “I have tried to assert the dignity and eternal importance of the human being in my Perhaps that was because she faced so much tragedy and trauma. When I look at Neel’s oeuvre, dignity is the operative word, the one that comes most quickly to my lips, even though I know it’s a complex idea, particularly when put forward as a major premise of human rights. In Neel’s work, dignity isn’t presented as a natural (or universal and inalienable) right. Rather, it’s much more caught up with responsibilities and recognition. For it to be real and lasting, it’s something other people need to recognize in you and vice versa.

Neel moved to 8 East 107th Street from the West Village in 1938 with the musician José Santiago Negrón. Their son Richard was born on September 14, 1939. Three months later, Negrón abandoned Neel and the infant. “I kept on painting,” Neel said of Negrón’s departure, “I used to work at night when the baby was sleeping. I was more an artist than A year later Neel met the photographer, filmmaker, and film critic Sam Brody and they began an on-and-off affair that lasted fifteen years. Brody, who was a founding member of the Workers Film and Photo League, an organization devoted to making art for social change, already had two children with his wife, the artist Claire Gebiner. Their marriage ended in 1941, the same year that Neel gave birth to Hartley—Brody’s third child and Neel’s fourth and final.

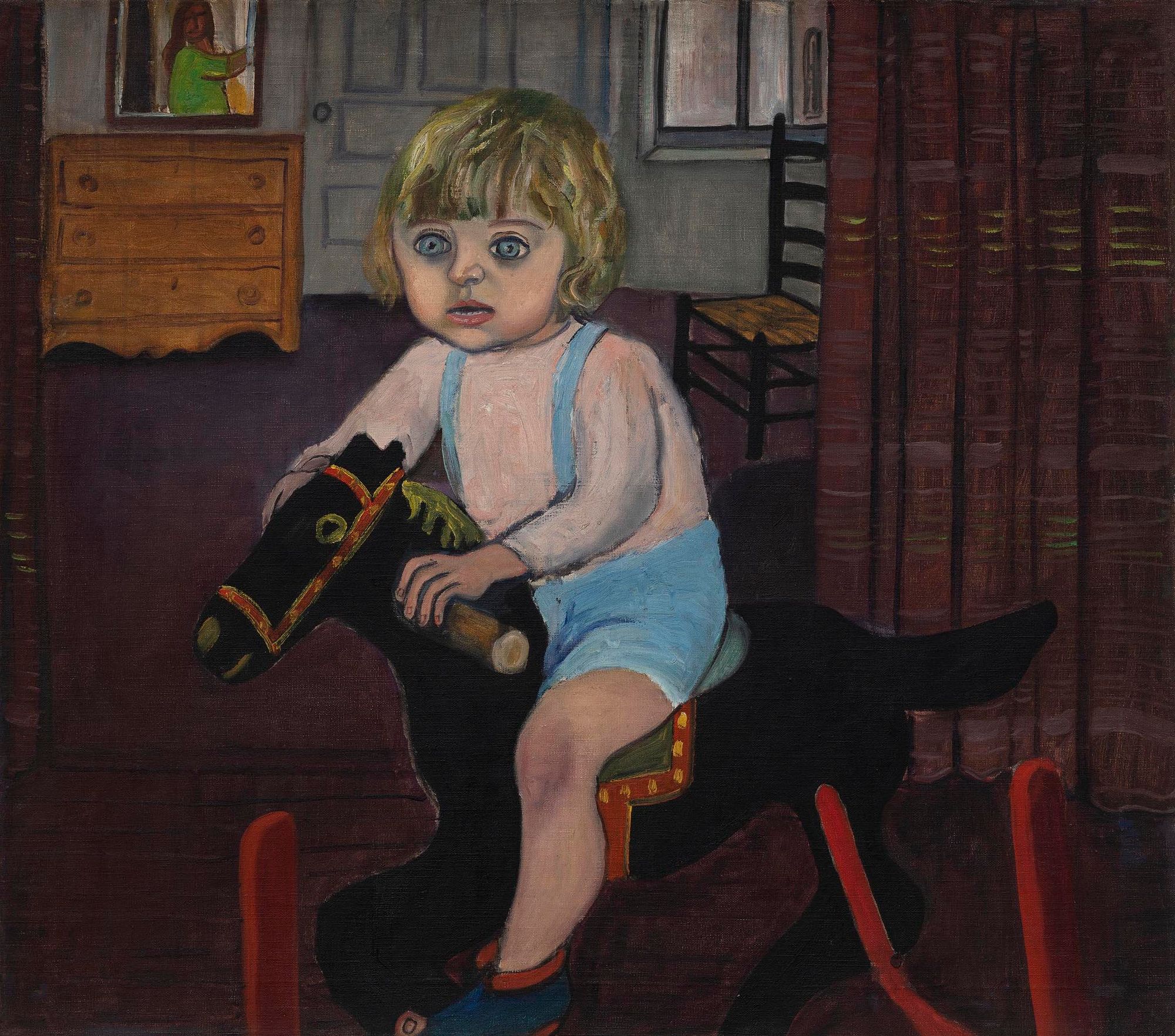

In September 1941 Neel moved next door to 10 East 107th Street and lived there briefly before landing on the third floor of 21 East 108th Street in November 1942, where she remained for the next twenty years. Brody would stay there occasionally. It was a large apartment and featured a living room with two south-facing windows looking out onto the street; this is where Neel painted much of her work. Neel’s relationship to New York City changed as her responsibilities shifted while raising two children on her own. To get by, Neel worked part-time at the Winfred Wheeler Day Nursery where the boys went, and taught painting for two years, from 1941 to 1943. The organization cared for orphaned children through WWII; Hartley was pictured on the cover of one of its brochures. According to Susan Rosenberg, “A sympathetic administrator helped Neel find work at the nursery, making it possible for her to remain in the Works Projects Administration (WPA) while also providing care for her She received fifteen dollars a week from the nursery. The WPA paid her around $100 per month. A neighbor named Mancie often cared for the boys while Neel worked or was out.

Two of Neel’s most remarkable paintings from her early years in Harlem, The Spanish Family (1943) and Building in Harlem (1945), offer a glimpse into what it meant to live and work there. The former is a coolly detached view of Negrón’s sister-in-law, Margarita, and three of her children: Carlos, Tommy, and Margarita. The unsentimental feelings evoked by their tired and distracted eyes, and the lack of warmth between them, speaks to a sense of honesty Neel was always pursuing. In portraits like these, I never have the sense that she was attempting to empathize in a touchy-feely, sentimental way with other people’s struggles. Rather, in The Spanish Family it seems more that Neel wanted to show that what really binds us together is a commitment to try to see the world from another person’s unique point of view, when possible, with your own eyes.

Building in Harlem is a tall picture of a neighborhood expanding upwards, under an impossibly sunny day. There is no urban despair here as three boys mill about on the corner, while trees with plentiful green leaves stretch upwards and onwards. Neel’s East Harlem wasn’t always one of sociohistorical portraits—of love and poverty—but sometimes just still lives of scenes, buildings, clouds, and sunshine. It was where she raised her family and it wasn’t always political. The same could be said for a later, related painting, Sunset in Harlem (1958).

Unfortunately, Neel’s experience with the WPA ended terribly. One of her WPA paintings was reproduced in an article in the April 17, 1944 issue of LIFE magazine, not in celebration of her art, but rather, as the article disclosed, because the government was selling the contents of its warehouses of WPA art as scrap canvas and insulation for four cents per pound. In 1943, Neel began to collect public assistance, which she continued to do until the mid-1950s. Neel considered welfare an extension of the WPA. Her son Hartley once recalled how caseworkers would occasionally visit their apartment: “We had to hide the TV and later the

Throughout the 1950s, the F.B.I. kept a file on Neel’s activities, which they deemed to be Communist. (She had joined the Communist Party while living on Cornelia Street in the West Village, during the Depression.) In an interview, Hartley recalled that two agents had once appeared at their apartment: “We were playing in the playroom. They came in their trench coats, these two Irish Their mother, who refused to respond to the agent’s various queries, offered to paint their portraits instead. The agents declined.

Sam Brody was physically abusive, mostly to Richard. There were broken bones and numerous threats. As Richard grew and could try to fight back, the situation spun out of control. From the beginning it outraged most of Neel’s friends and family though she barely spoke about it in public. In a rare statement she said: “You know what Sam and I were? . . . homicidal meets In her biography of Neel, Phoebe Hoban notes that finances seemed to have been part of the artist’s motivation to stay with him. Sam gifted Neel thirty dollars a

Hilton Als has commented on Neel’s proclivity to abhorrent behavior:

When others describe her psychological difficulties—her proclivity for troubled partners and so on—it strikes me that it was her way of paying for what she felt was an overabundance of privilege. If she was stripped of it by feckless lovers and the like, she would be more real. Pain would be her portion; it would neutralize her tremendous gifts and make her more like other people, other

It’s hard to know if Neel thought she was “paying for” her privilege. What’s clear is that Neel was completely focused on her work, and if an abusive partner wouldn’t go away, perhaps it didn’t matter as much as putting food on the table. But I take Als’s point—and he’s also right that you have to “search your own shit” to understand Neel’s When I look at Neel’s portraits of her young children, I think of my mother, who became single when I was two. My father was a nascent addict, and the situation became too difficult to have him around. But he never really went away, just dipped in and out, and that presence/absence game is something Neel seems to have known intimately. I sympathize with her comfort in ambiguity. It’s what we see in her portraits: People just trying to get by as life goes on, as other people come and go, continuously. Her pictures are mixed with equal parts love and sorrow, but in the end, it really is dignity that she wants to present—even in her heartbreaking 1943 self-portrait on paper with Richard, where she appears zombie-like, as though she had not slept for months, holding her downtrodden child. They materialize under a harsh light, as if in a psych ward.

Of her choice in men, Neel once remarked to an audience in St. Louis in 1976: “When I picked men, I picked them the way rich businessmen pick ladies. I picked ones who are beautiful. One reason I liked far out people is that boring childhood in that small town. You know, people think I’m a bohemian, just jumping from one thing to another, but I went through hell each time.” And then she offered one of the greatest artist statements of all time: “I have so much history. If I didn’t unload it, I wouldn’t have any

Subscribe to Broadcast