These Fragments I Have Shored Against My Ruins

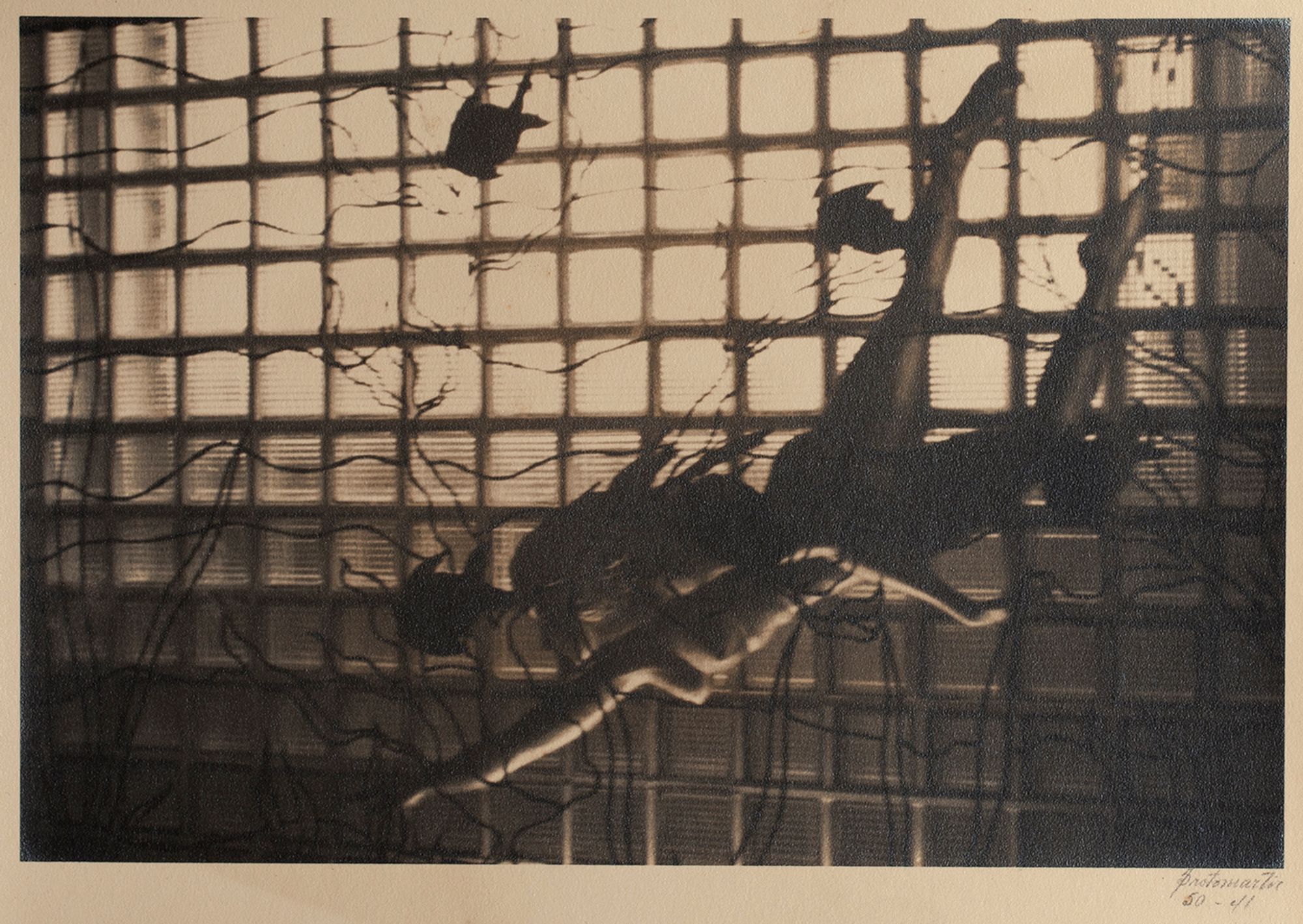

In Teodulo Protomartir's (1902-1977) After the Parade, a man rests under a sampaloc (tamarind) tree on the sidelines of a public ceremony that marked the official end of US colonization of the Philippine Islands on July 4, 1946. The man is glancing at something offscreen and away from the events on the grandstand, which are signposted by a Philippine flag flying aloft in the center of the image. Unlike in mainstream documentation of the Philippine Independence ceremony created by journalistic wire photos and official government footage, Protomartir’s camera moves along with the crowd. In another photo, After the Celebration, subjects that would be typically centered in such photographs—the US Army jeeps, the Philippine and American flags flapping mid-air, the burned out buildings of the Bayview and Luneta hotels—recede in the background, behind the real subject: the crowd’s point of view.

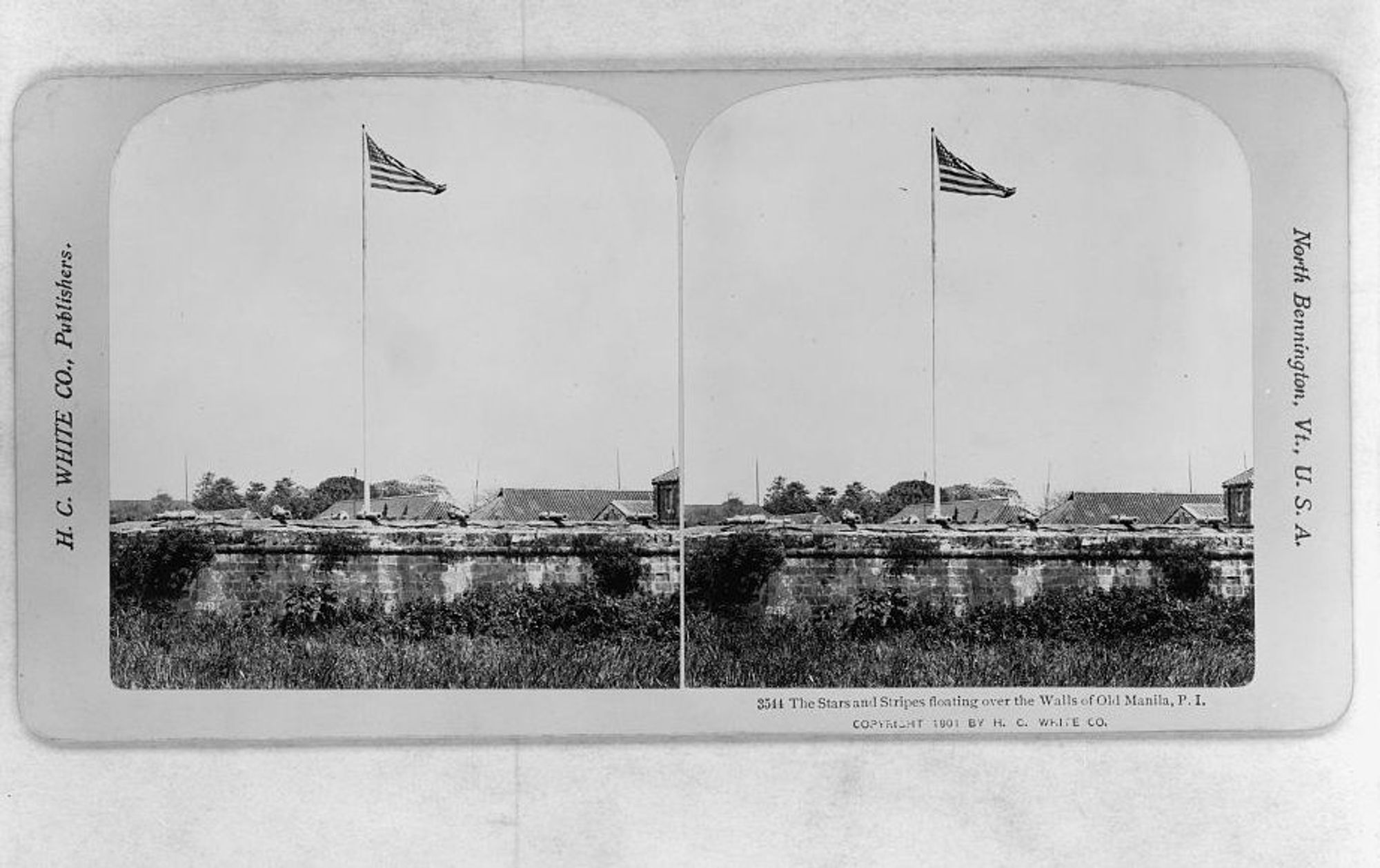

After the Parade is a striking counter-image to colonial pictures such as the 1901 stereograph, The Stars and Stripes Floating over the Walls of Old Manila. In his analysis of colonial photographs, Christopher Capozzola argues that the camera was instrumentalized as a technology of conquest. Even the “slow and cumbersome” photographic apparatus of 1898 was still “among the most technologically advanced and complex portable instruments that American soldiers carried into battle.” Simply put: “the Army understood that mastering the photographic image would be key to waging war.” Stars and Stripes was taken by the US military in August 1898 to mark their victory over Spanish forces in the Philippine islands. (Not long after the image was captured, however, US forces faced the Philippine Revolutionary Army, who, having declared their independence from Spain, was unwilling to submit to a new colonizing master.)

Capozzola notes that as this terrain was completely unknown to the US military in 1898, photographs allowed them to compile visual intelligence about the “transportation and communication networks of the Spanish and Philippine armies.” But what captured the popular imagination on both sides of the conflict were the ethnographic photographs taken by US forces. Such photographs “were weapons in the ‘pacification’ of an independence movement” that garnered broad popular support among Filipinos.

Protomartir’s choice to depict the 1946 ceremony celebrating the end of US colonial rule from the sidelines reflects an aesthetic and political stance that is both anticolonial and modernist. The man looking offscreen registers the disconnect between the pomp and circumstance of the grandstand’s stage-managed proceedings and the aspirations of the generations of Filipinos involved in anticolonial struggle. There is also a distinctively formalist quality to the composition of the image, with the bold V formation of the sampaloc branches framing the Philippine flag and splitting the image into three abstract zones of action. Gripping a slender tree branch, the gazing man’s action is mirrored by another spectator who is cropped out of the frame. This composition suggests that the events transpiring in the distant grandstand are less compelling than the charged reality unfolding from the margins. And unlike popularized ethnographic imagery, Protomartir’s camera does not objectify people as specimens. They are captured instead as active subjects of history in the making.

After the Parade and After the Celebration were first found languishing among the cache of decaying films—stuck inside a single 1930s model Kodak Folding Camera—that camera-collector Uro De La Cruz discovered in 2007. As De La Cruz writes in an article, the camera was in local antique dealer George Bonsay’s boutique in Kamuning, a street in Metro Manila. Inside the camera was an empty metal reel, and pasted to its back cover was a sheet of paper with minute inscriptions—faded, practically undecipherable. Studying them, De La Cruz realized that these marks were experiments in switching aperture and shutter speeds. De La Cruz had been collecting pictures of shuttered theatres, so Bonsay showed him more of Protomartir’s photographs in plastic envelopes, night shots of Avenida Rizal (Avellana’s Anak Dalita flashed across the marquee of the Dalisay theatre, dating the photo to 1956). Declaring that the creator of these photographs is the “Father of Philippine Photography”, Bonsay urgently solicited De La Cruz’s help with the deteriorating negatives, which were so fragile that photo developers refused to touch them. When De La Cruz enlisted an expert’s assessment, Jay Javier of Fotofabrik studio, the diagnosis was Vinegar Syndrome, or when the plasticizer in the film base leaks and makes the film very brittle. De La Cruz carefully scanned and digitally cleaned each negative, each and every 30,000 of them.

De La Cruz spent around two years preserving Protomartir’s negatives, hoping that there would one day be a chance to share them with the world. That opportunity came in 2010 when Silverlens Gallery worked with De La Cruz to scan around sixty of Protomartir’s postwar Manila photos, taken between May and June 1946, for an exhibition titled Being There. It has been more than a decade since this last exhibition and while it sparked a small interest, Protomartir remains an obscure figure. De La Cruz died in 2016.

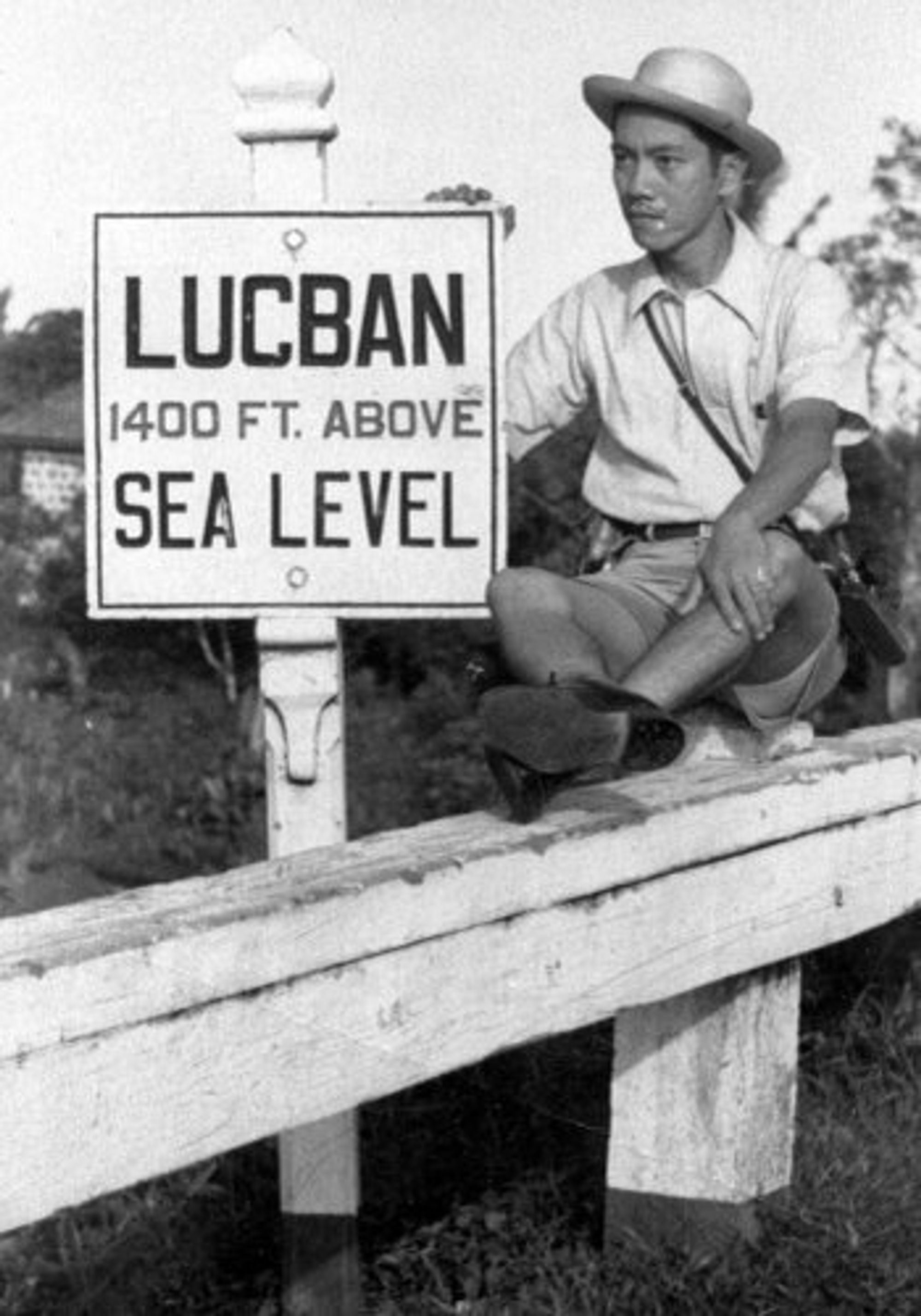

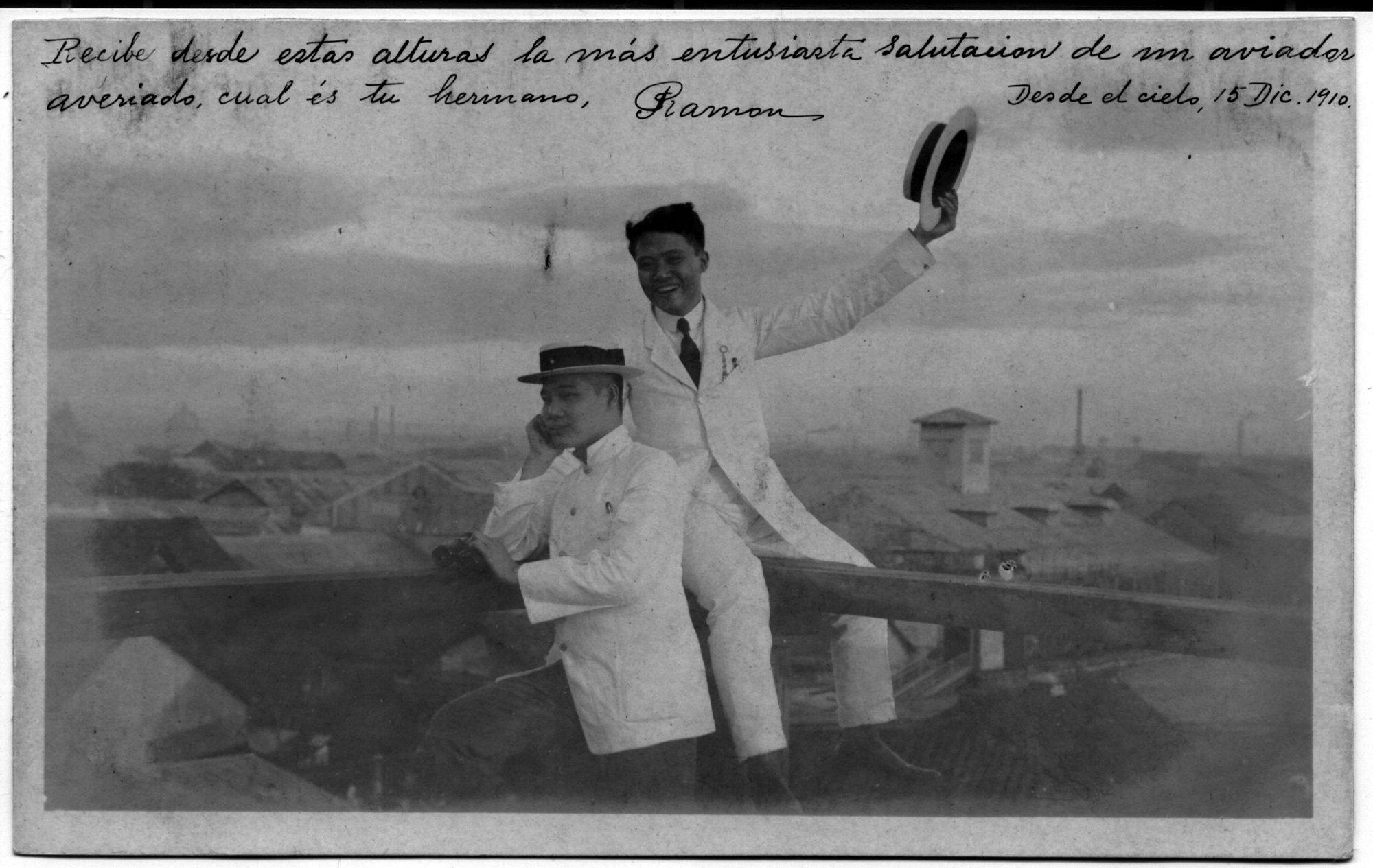

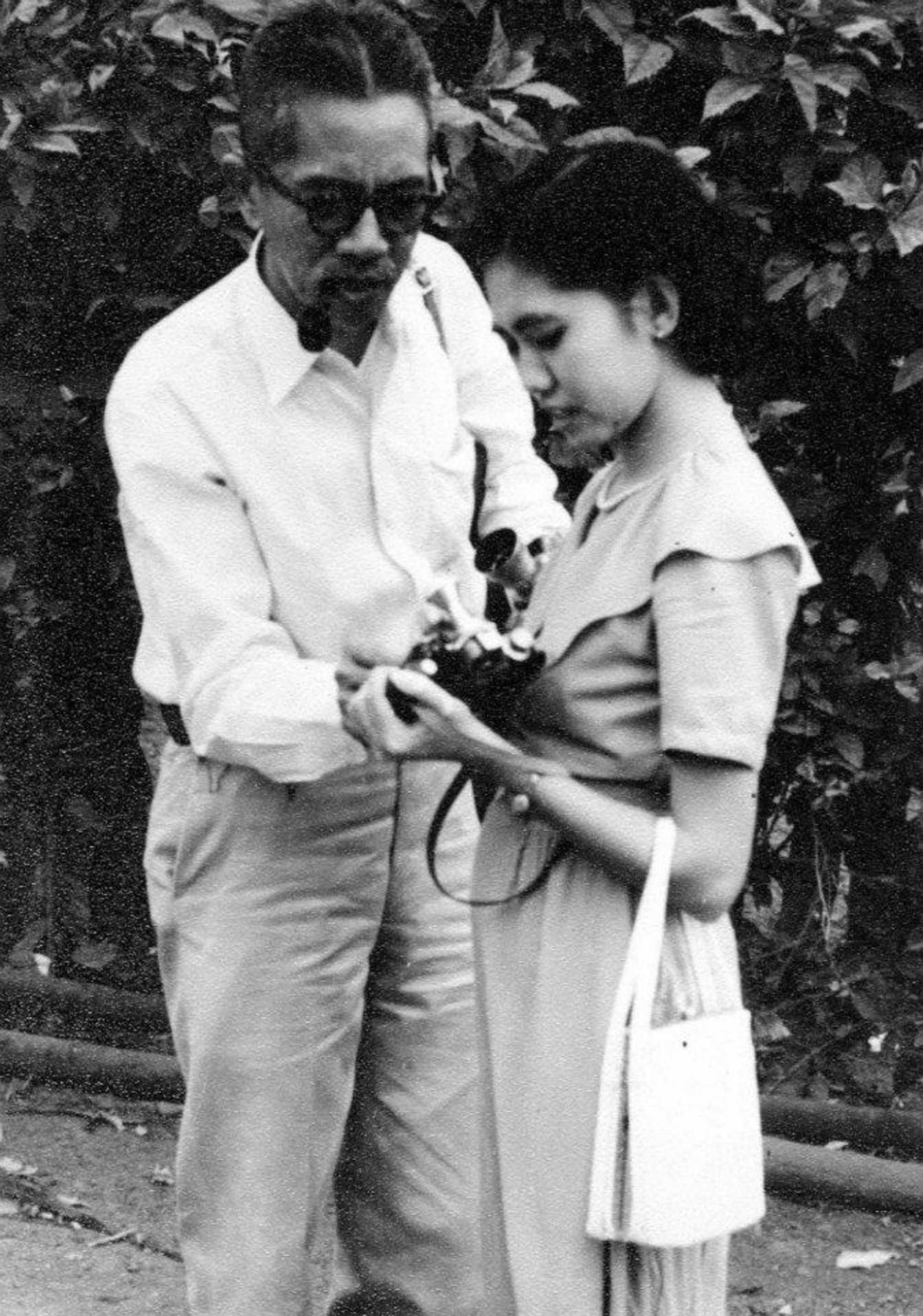

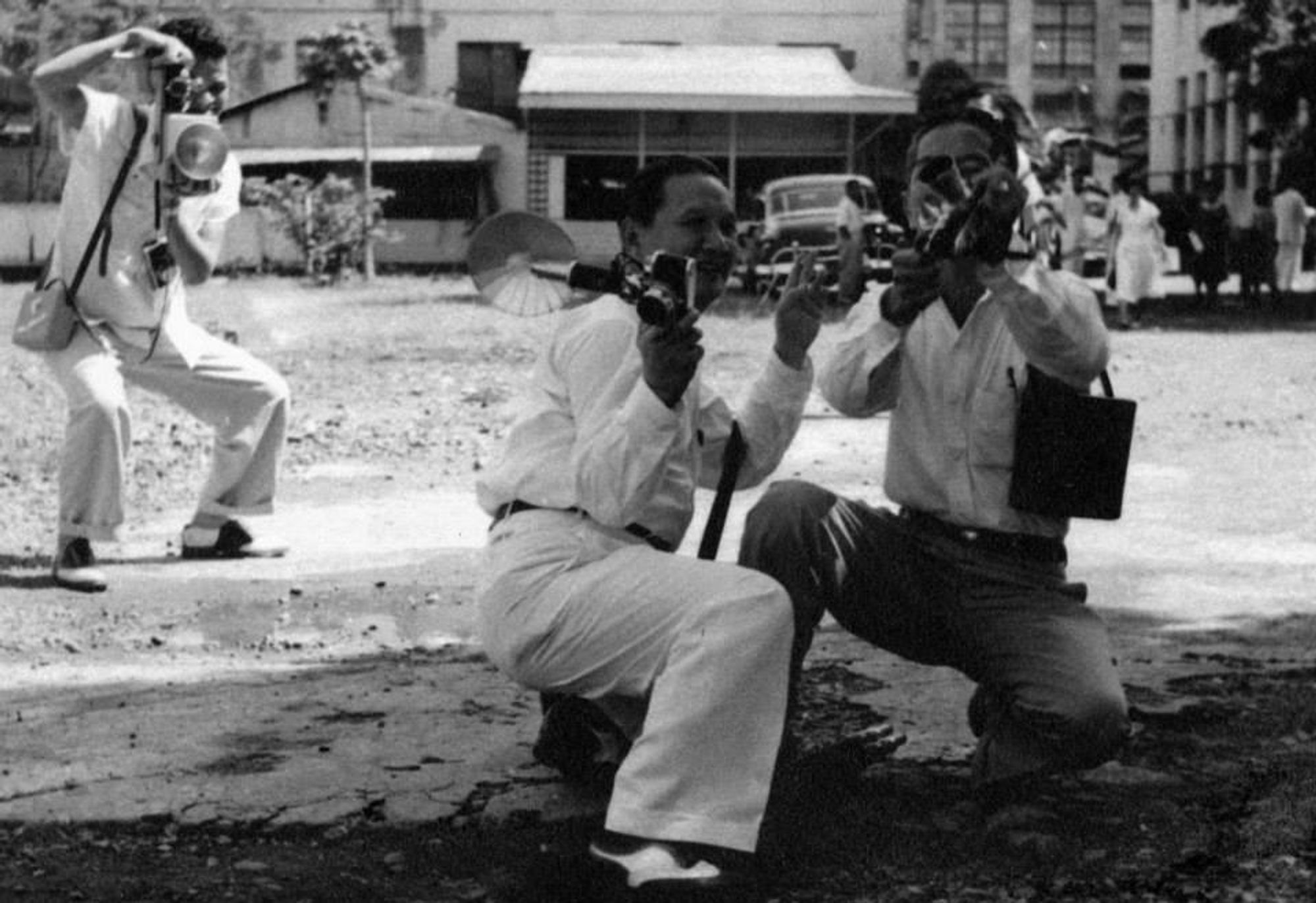

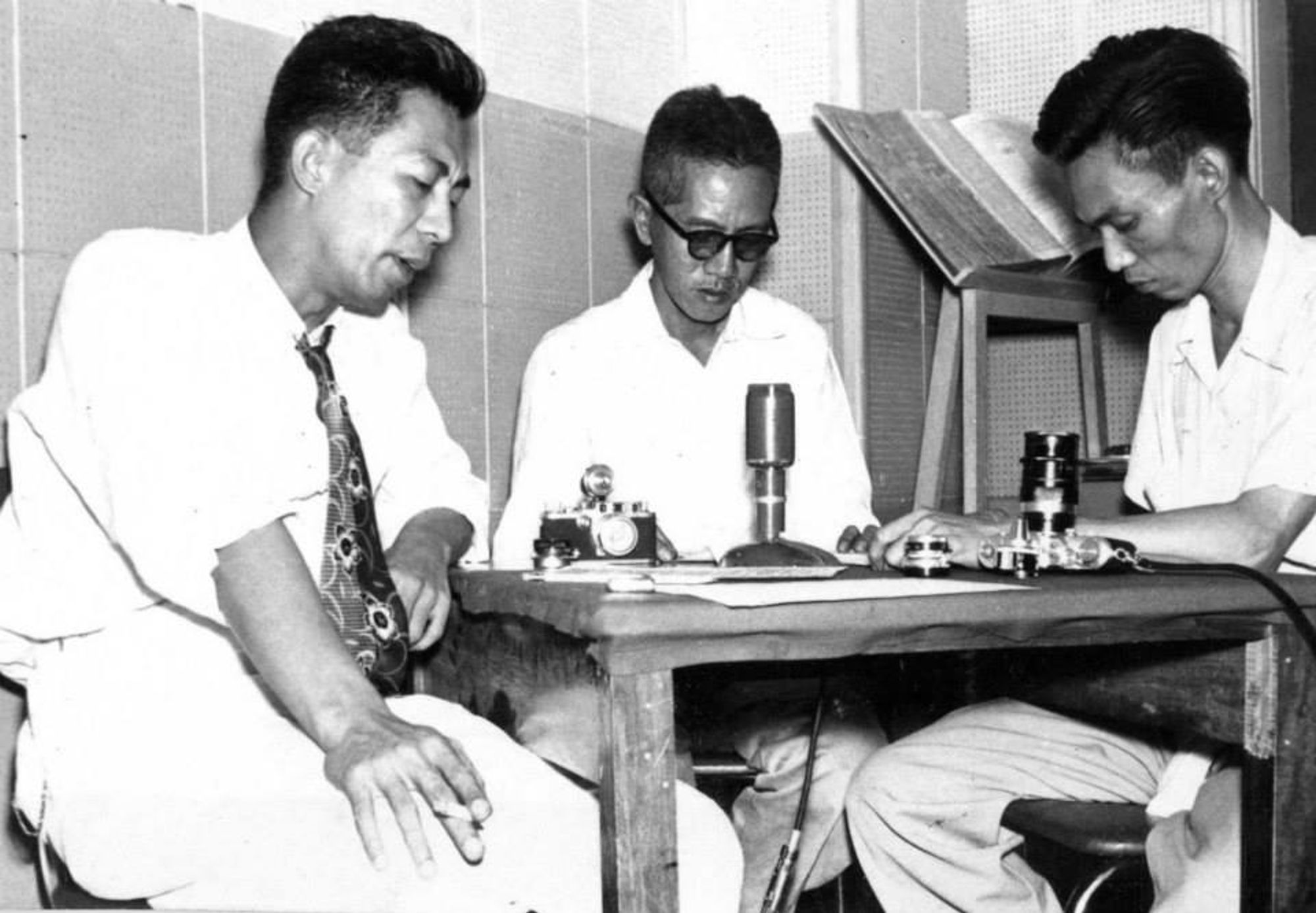

There is very little known about Protomartir’s life. Born on February 17, 1902 and died on February 6, 1977, he was among the first to shoot in the 35 mm format using newly released mass-produced cameras. He was a tireless educator and advocate of the medium: beyond mentoring younger photographers as a university professor, he published a book in the US titled Glimpses of the Philippines (1948), and hosted a radio show focused on photography as a mass medium. He also founded the 35 mm Club, one of the first civic organizations of photography enthusiasts in the country. Its members used the newly manufactured, smaller portable cameras, which made photography accessible to the general public for the first time. This democratic model contrasted with the more established Camera Club of the Philippines (founded in 1928), which drew its membership from elite enthusiasts who likely used prohibitively expensive cameras. As De La Cruz describes a photo of a young Protomartir with his peers in a walkabout, “they were all proudly wearing two-toned shoes and [around] their necks were rangefinder cameras. It was the 30s, 35mm film was fairly new, and these young photographers were pioneering something that went against the norm, when large format cameras were the accepted tools of the medium.”

Protomartir’s daughter Nena Tan recounts in a 2019 video interview that her father kept a day job at Botica Boie (the pharmacy that was locally famous for formulating the distillation of high-grade ylang-ylang essence) and travelled every weekend with his camera club to capture the city and its environs. She surprisingly noted that he was not interested in publicizing his photographs. If he had an audience in mind, one could surmise that it was his camera club. In the interview, Tan asserts that Protomartir shunned commercial applications of photography and, as she repeatedly emphasizes, disliked taking portraits of people.

Protomartir’s rejection of portraiture is defiant in the context of the studio portrait as a class symbol in colonial Philippines. The bourgeois studio portrait was itself a rejection of colonial imagery taken by Americans. According to scholar Alfred McCoy, Filipino subjects were portrayed in these photos as “objects of scientific study or simple curiosity” and were posed “in ways that made them seem depersonalized and culturally inferior.” Subjects were photographed in the nude, through head shots intended to determine skull shape, or juxtaposed with the bodies of colonizers to “establish” the biological superiority of the former.

Among the most influential of these ethnographic photos were those taken by Dean Worcester in conjunction with the Department of Interior, which he directed from 1901-1913. A large corpus of Worcester’s photos were produced under the aegis of the so-called Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes, which sought to document “little-known pagan and Mohammadan tribes of the archipelago” and recommend “legislation in behalf of these uncivilized peoples.” Worcester and his team took as many as 10,000 photographs, which are now archived at the Museum of Natural History in New York City, and the Field Museum and the Newberry Library in Chicago.

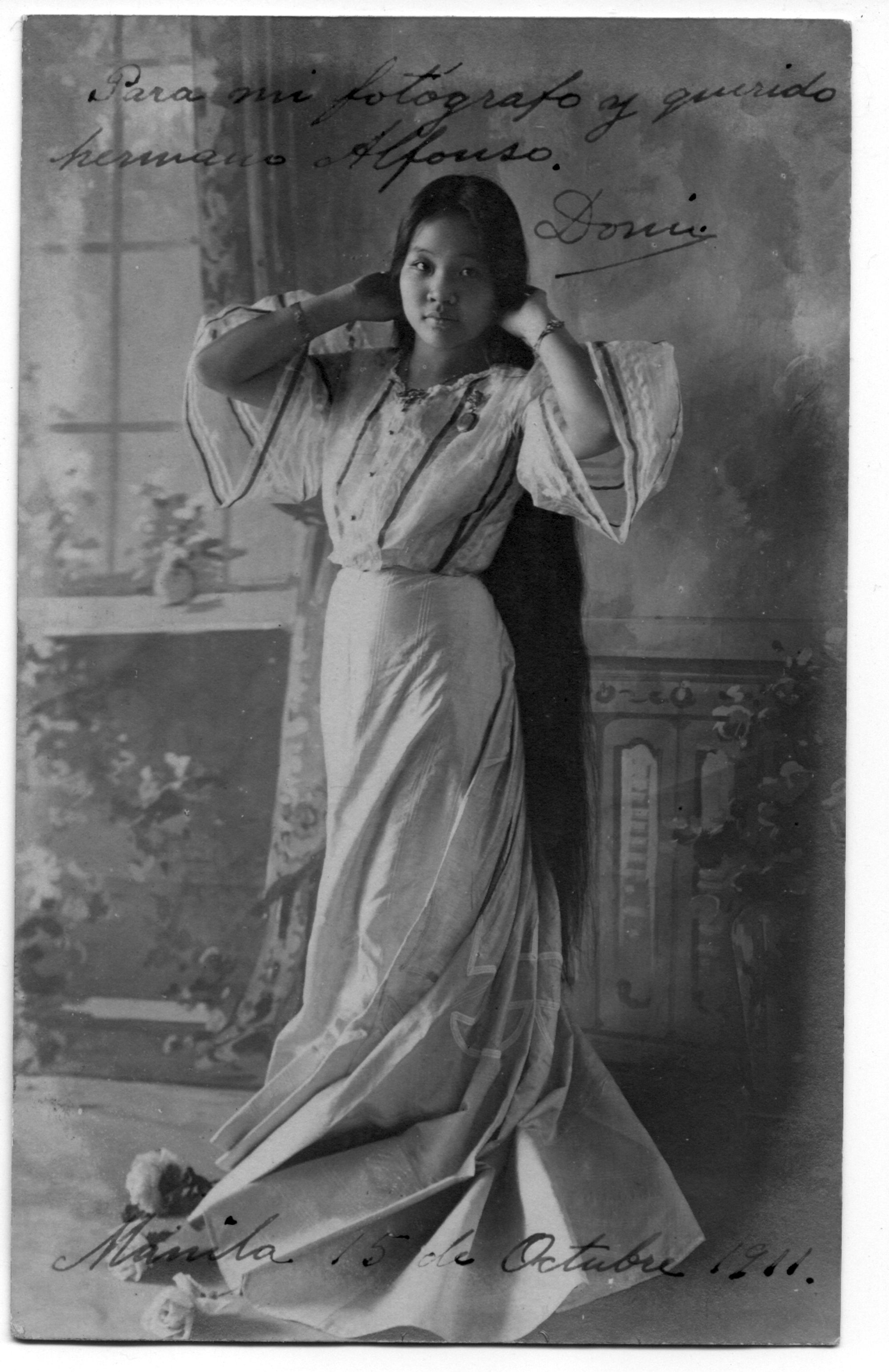

Historian Vicente Rafael’s study of the photographic portrait in colonial Philippines notes that as with the bourgeoisie in other areas of the world from the late nineteenth century on, Filipinos who sought to identify with this class posed in studios as a means of asserting visual sovereignty. As exemplified by the works of photographers like Alfonso Ongpin (1868-1948), studio portraits of the 1910s and 1920s constituted the Filipino bourgeoisie’s visual language of self-fashioning.

By presenting Filipinos as civilized and cosmopolitan, Ongpin’s family album foiled the depersonalizing ethnological portraits popularized by Worcester and his ilk. Yet class and caste are entangled with self-fashioning, as portraiture was a form that only the Filipino bourgeoisie could afford. And though the Ongpins were known to side with revolutionaries during the Philippine Revolution and the war against Americans, most Filipino bourgeoisie families switched allegiances. As Rafael puts it, these elites “fought against and collaborated with Spain” in the revolution between 1896-1897, and having “fought against then collaborated with the United States afterward,” saw themselves as “the very embodiment” of the nation and held a monopoly on the ability to speak for it.

Ultimately, this tactic of self-presentation kept them in a deadlocked conversation with the colonizer, whose markers of power dictated the terms through which they attempted to exercise subversion. Their performance of civility captures the conundrum of the colonized trapped by the colonizer’s gaze, as parsed by Fanon’s study of colonialism’s psychological effects in The Wretched of the Earth: “The Negro, never so much a Negro as since he has been dominated by the whites,” must inevitably “prove that he has a culture and behave like a cultured person.”

Though Protomartir belonged to the same social circles as Ongpin (they served together as officers of the Philippine Antiquarian Society and the Philatelic Club), his practice could not have been farther from using portraiture as a means of achieving recognition from the colonizer.

Protomartir’s photographs have been compared to the American amateur genre Salon Style which its advocates claimed “liberated” the traditional photograph. But Protomartir’s practice went beyond aping Western genres. His consistently modernist aesthetic sensibility indicates that he was just as concerned with the technicalities of producing an excellent photograph as he was with capturing the zeitgeist.

After the second World War, Manila embraced the importation of change and modernity. Protomartir imbibed the spirit of modernist photographers who embraced crisp lines and abstraction in form, and who invariably saw the perfect subject in the changing city. As Alfred Stieglitz had declared about New York, Protomartir’s Manila was the Manila of transition.

These works suggest an aesthetic affinity with André Kertész, who primarily approached photography as a medium for observing everyday urban life. Protomartir recreates a famous 1917 photograph by Kertész who took up swimming after being injured in the First World War, and during this physical therapy noticed the distortions that water creates on the body. The body in Protomartir’s Underwater Swimmer obliquely suggests the representation of personhood that one finds in a portrait; yet, as with Kertesz’s swimming form, the subject is anonymous. A similar effect is achieved in Protomartir’s untitled sculpture of a soaring woman reflected on water. Both are abstract studies of the body that shun the representation of status and power in the bourgeois portrait.

Protomartir’s images of Manila are indeed sparsely populated with human subjects—when they do appear, they are fleeting shadows, anonymous figures (such as a stevedore, a shopkeeper, or an office worker). They exist as metonymic extensions of the city and the landscape, which are in turn allegories of the postwar nation. Anchors of his oeuvre, Protomartir’s Manila ruins mark the passage of the colonial era to the post-independence era. His camera often isolates details that easily escape a touristic gaze. In one photograph, the Manila Cathedral, the centuries-old bastion of the Catholic Church, is seen in juxtaposition with a statue of three priests who were executed by garrote following a mutiny they allegedly led against the Church in 1872. Shot from a low angle, the photo only shows the crucifix, the nave roof, and the upper portion of the statue. In another photo, four stevedores carry sacks of rice along an improvised wooden plank that connects the pier to the ship. Taken from a discomfiting low and tilted angle, the men appear to be walking a tightrope that would tip them into the water at the slightest gust of wind. But the scene seems strangely devoid of the hustle-bustle one would expect from a city photograph. The shot’s abstract quality evokes the city as a machine, the men as parts of its grand mechanism. These images, which often magnify isolated details or zoom out into an aerial view, distinguish Protomartir’s practice from conventional photojournalism. The unusual framing, bold graphic compositions, and dramatic lighting invite the viewer to see the city anew.

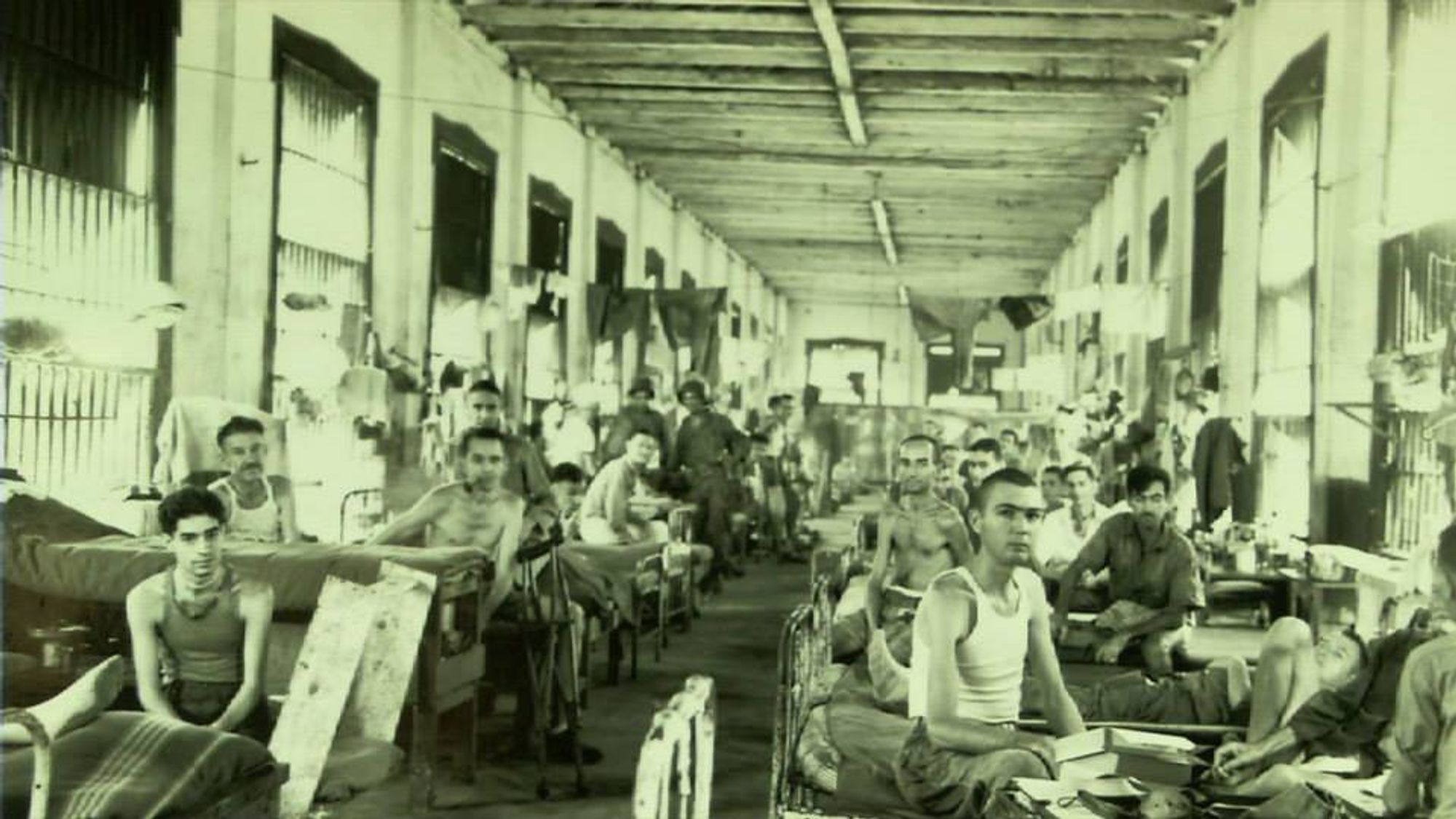

“These fragments I have shored against my ruins.” These lines from T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land ring through Protomartir’s photographs of postwar Manila. An old world was being torn down stone-by-stone, and Protomartir understood that it was imperative to preserve fragments of this erasure. He risked his life to document the bombing of Manila in 1945. He captured the dramatic skyline of the burning city, US soldiers attacking the Japanese stronghold at a baseball stadium, civilians carting the dead through chaotic streets, and American soldiers in prison camps. Unlike his other compositions, these photos have the immediacy and legibility of photojournalism. In almost every photo Protomartir took of Manila’s rebuilding after the war, traces of postwar ruins frame the shot compositions.

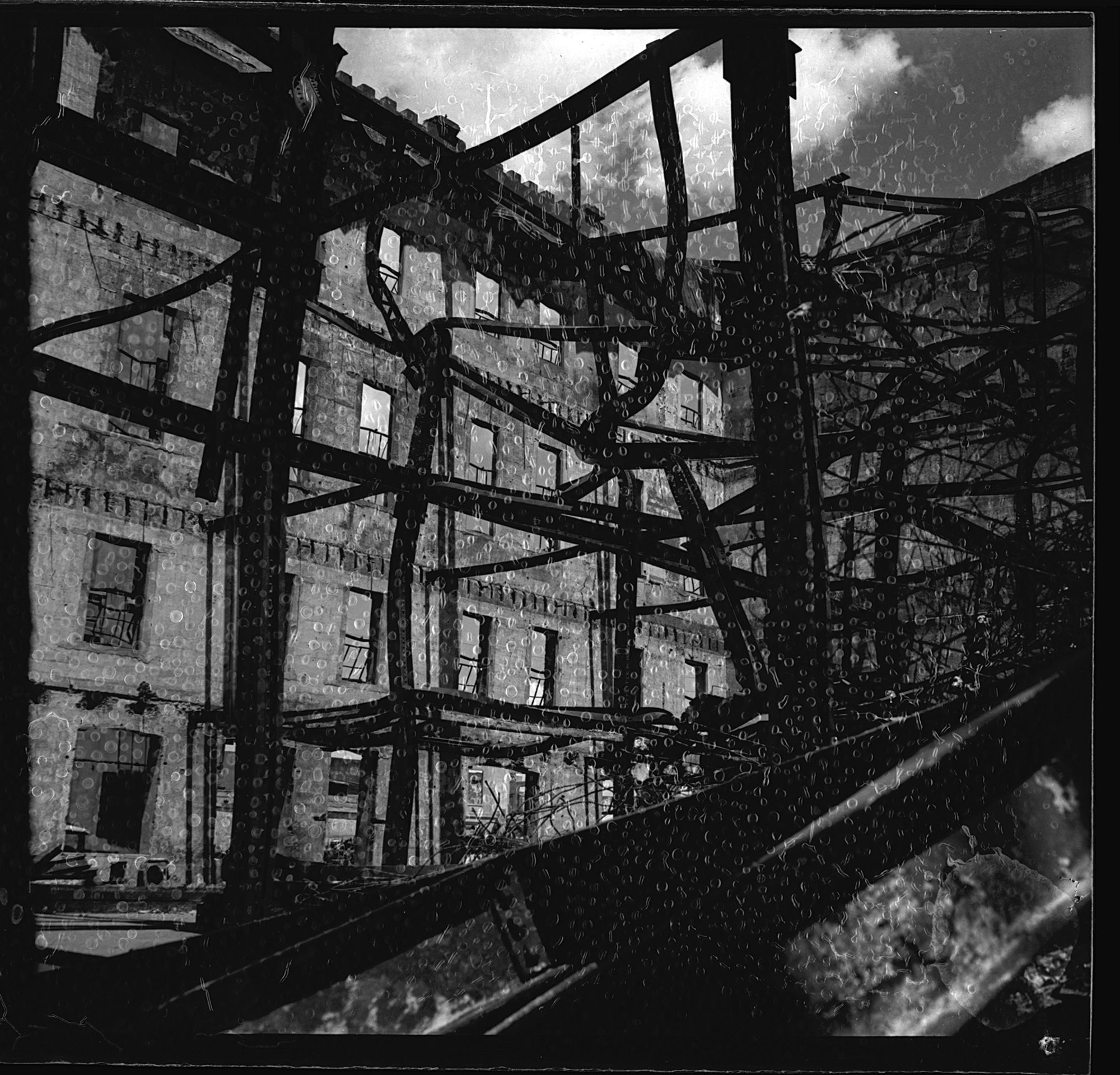

Protomartir photographed the Metropolitan Theatre, which escaped destruction during the Battle of Manila, from behind the warped gates of the Insular Ice Plant. Built by Americans during the colonial period in 1902 to “provide supplies and comfort” to US troops, the ice plant was one of the first permanent structures of its kind in Southeast Asia. In Protomartir’s photo, it exists as a symbol of power, or rather, the loss of it. A contemporary audience would know that the plant was all but destroyed in the Battle of Manila.

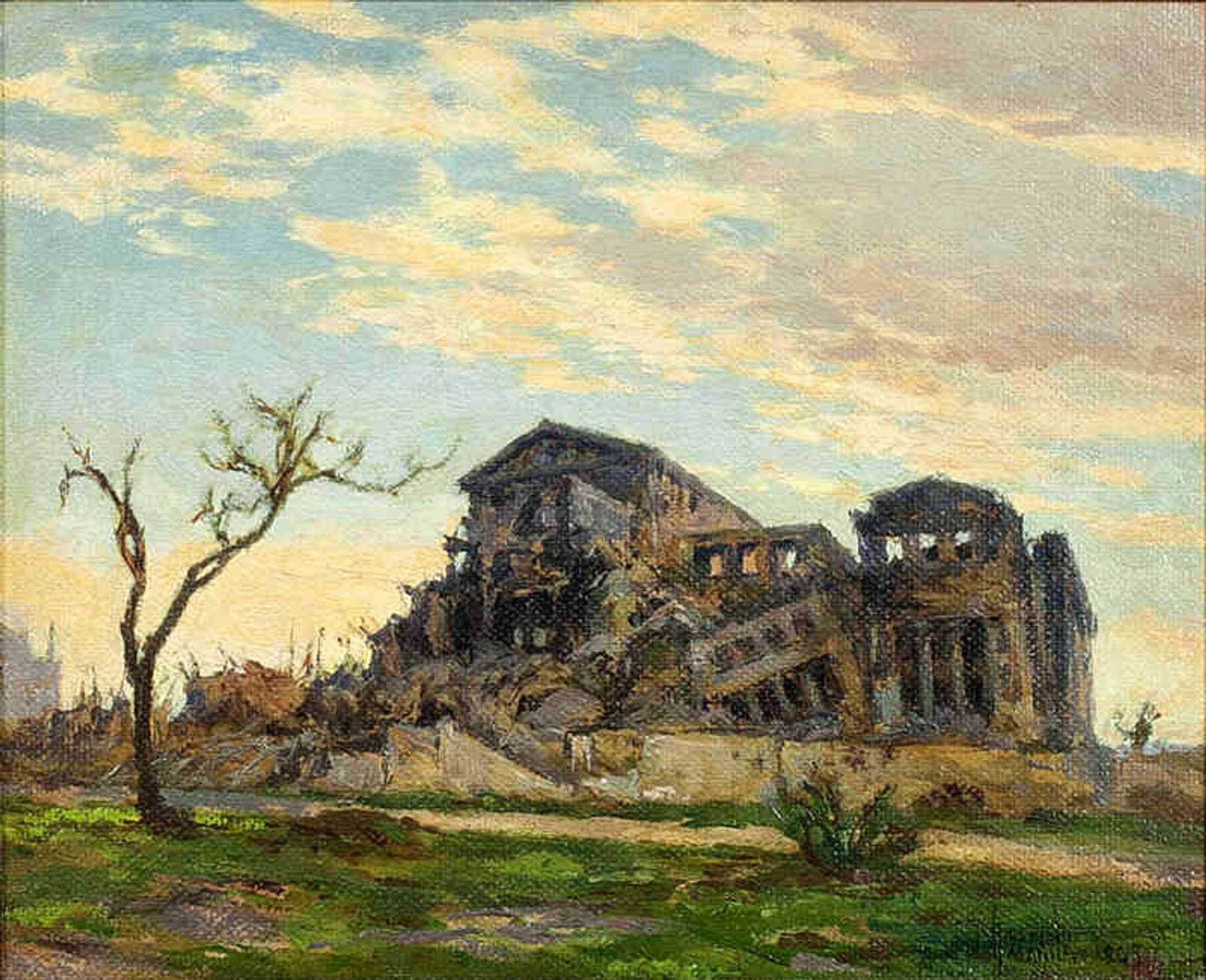

In another photo, the crumbling structure of the Legislative Building is framed by the steel remains of a US tactical truck. With only the portico left intact, the ruins of the once-magnificent neoclassical structure were immortalized by painter Fernando Amorsolo in 1945. In Amorsolo’s painting, the continuity of earth to the rubble depicts ruination as an equilibrium between architecture and nature, a fleeting period where neither have the upper hand, before nature’s inexorable force prevails. Protomartir’s ruins, by contrast, render the seams of the built environment visible, and emphasize the Legislative Building’s structural damage in contrast to neighboring Manila City Hall, which was left unscathed. The ruins framed through the skeleton of a US army truck reminds the viewer of the building’s colonial pedigree: originally intended as a public library, it was built by the Bureau of Public Works (1918-1921) to house the Legislature and the colonial government’s collection of Philippine artworks and ethnographic artifacts. The truck is also a visual reminder that American artillery destroyed the building and what would have been the national art collection stored therein.

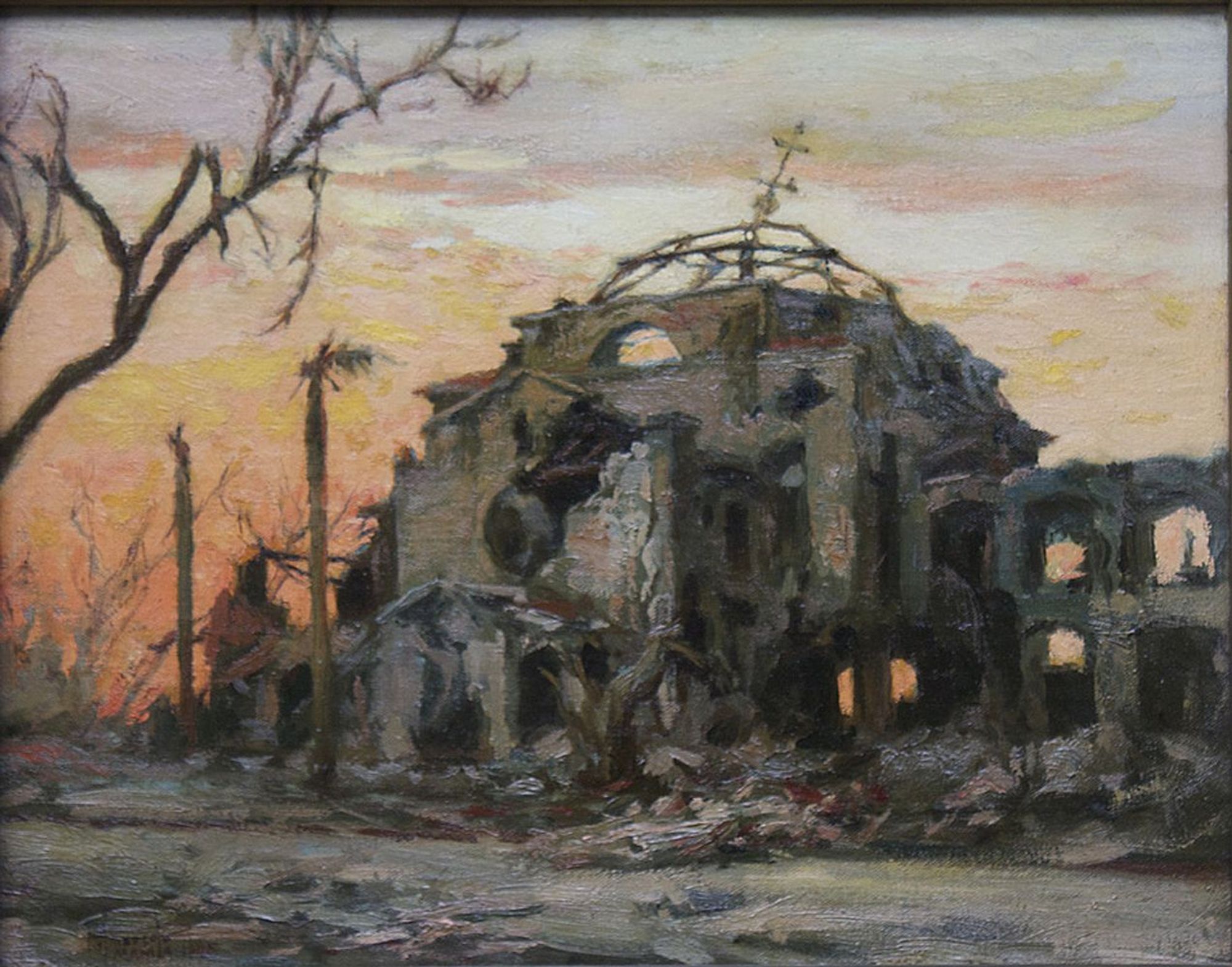

Protomartir’s images suggest his ambivalence about the new city rising from the rubble. Contemporary observations about Manila’s swift urbanization—its worsening traffic conditions, booming nightlife, explosion of mass advertising—filter into the mise-en-scène of these photos. In a photo of an empty café at the Capitol Theater (which survived the war but was demolished in 2020), natural light from one window barely illuminates the table settings. Like Protomartir’s church ruins, the somber scene calls to mind an absent congregation. And yet, the welter of billboard signs from the business district through the windows comes across as an intrusion into an otherwise serene tableaux. Related to his pre-war photographs of newly available leisure and entertainment amenities, these images are striking counterpoints of those of church ruins in the walled city of Intramuros. Here, light, space, and color have a hallucinatory intensity that embody the changing sensorium of the metropolis.

Fernando Amorsolo, Ruins on Rizal Avenue, signed and dated 1945, oil on masonite board, 17 x 25 in.

Photo courtesy of Leon Gallery.

Teodulo Protomartir, From T. Pinpin corner San Vicente, 1946, archival inkjet print.

Photo courtesy of Silverlens Gallery.

Fernando Amorsolo, Cathedral of St. Mary and Joseph, 1945, oil on board, 12.25 x 16 in.

Photo courtesy of Frazer Fine Art.

Teodulo Protomartir, Lourdes Church Ruins, 1946, archival inkjet print.

Photo courtesy of Silverlens Gallery.

Teodulo Protomartir, Manila City Hall, n.d. circa 1946.

Photo courtesy of Luzviminda Collection published with the permission of Pacita Protomartir Tan and Protomartir Family.

Protomartir transformed the camera from an instrument of colonial conquest to a democratic medium for a newly independent nation. Over the course of six decades, he produced a singular collection of black-and-white photographs that combines formal acuity with an insider’s point of view. Countervailing the notion of the photograph as mere document, his pioneering work privileged the medium’s aesthetic qualities, and helped it gain acceptance as an art form in its own right. Yet, as his photographs must be regarded as part of his civic endeavors, his legacy is not only as a photographer but as an educator and collector.

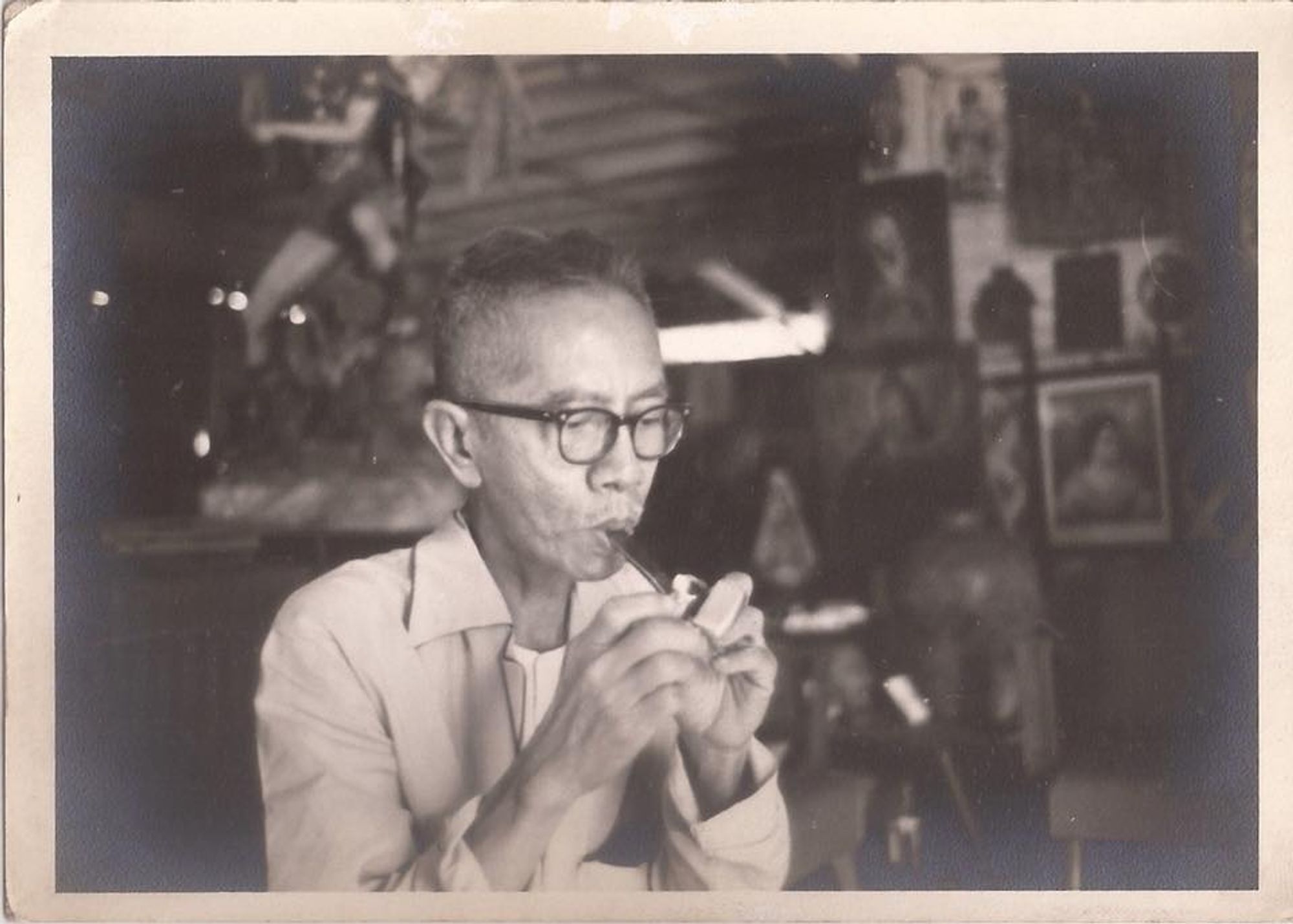

Protomartir deemed collecting antiques and artifacts as part of his intellectual practice. In the absence of a National Museum, Protomartir filled a cultural vacuum by building an elegant study and exhibition space for his community. There was scant interest in the art market in reconstruction-era Manila, so he was unlikely motivated by profit. He welcomed visitors into his home in San Juan, east of Manila, where his antiques were stored on the ground floor; behind it was his darkroom. Upstairs was mostly for living, but also served as storage space for his artworks, collection of stamps, newspapers, magazines, and books, and other relics. His children felt at times that the San Juan home belonged less to them than the memorabilia. Protomartir’s passion for collecting demonstrated his commitment to creating an archive for what he envisioned would be a sovereign Filipino state after 1946. As technological advancement outpaced his photographic approach, he found himself shunning opportunities to exhibit his work and retreating among his collection. His photographs and antiques have been discovered fifty years after they were given, bought, and sometimes stolen. A collector who stumbled upon Protomartir’s self-portrait in Hong Kong found it was mislabeled as that by a “Vietnamese Man.” Though he collected treasures for the appreciation of a future generation, his own work would end up fragmented and dispersed. With the passing of his main archivist De La Cruz, Protomartir’s legacy, his significance to Philippine art and photography, needs to be salvaged and reconstructed. ♦

Editor's Note: An earlier version of this article stated that Teodulo Protomartir was "likely born in 1910." Since the article's publication, Protomartir's surviving relatives have supplied the exact dates of his birth and death. The author would like to thank Katya Guerrero of Luzviminda.ph for issuing this correction.

Subscribe to Broadcast