Molly Crabapple: Fiesta de Loiza

It's an ironic fact that the patron saint of Loiza, the most African town in Puerto Rico, is Santiago Matamoros—St. James the Moor Killer. Matamoros's origin story dates from the year 859, and a battle that supposedly took place between Christian and Muslim armies in Clavijo, in northern Spain. The followers of Jesus, at a desperate moment in the fight, looked up to see the clouds part and St. James ride down on a white charger, sword in hand, to save the day. Or so the story went. None of it happened, of course, not even the Battle of Clavijo. But this didn’t stop St. James the Moor Killer from becoming a veritable symbol of Spain by the time the Reconquista rolled around, who was often portrayed as a knight on horseback, riding over the severed heads of turbaned Muslims. When Spain's colonization of South America began, Matamoros took on a new guise: he became a conquistador named Mataindios, Killer of Indians.

Winners like to relive their victories, and the Spanish are no exception. For nearly a thousand years, they've staged festivals of Knights and Moors that are half raucous carnival, half ahistorial reenactment of battles between noble Christendom and devilish Al-Andalus. When Spain colonized Puerto Rico, they took these celebrations with them.

But that’s where things began to shift. In Loiza, the Blackest town in Puerto Rico, a cradle of Afro-Boricua culture outside San Juan, these Knights and Moors started to look different. The Yoruba artists who made costumes for the festivities that took place on Matamoros's saint day, July 25th, had a different understanding of the Reconquista, and of who its angels and devils were. The “knights” they created were grotesque, hilariously foppish satires of their white hacendado oppressors. The “moors” became vejigantes: exuberant tricksters in bright African masks. Soon, the vejigante became the symbol of Puerto Rico, iconic enough to merit his own Marvel miniseries and so ubiquitous that my father hung a small vejigante mask by his office’s doorway at the university where he worked.

In 1898, the United States colonized Puerto Rico. Through the 1950s, America’s government encouraged the mass migration of Puerto Ricans like my father’s father to New York City. Here, they took low wage factory jobs and settled, amongst other places, in East Harlem. Many who came were Loiza's sons and daughters, and they brought their celebrations with them.

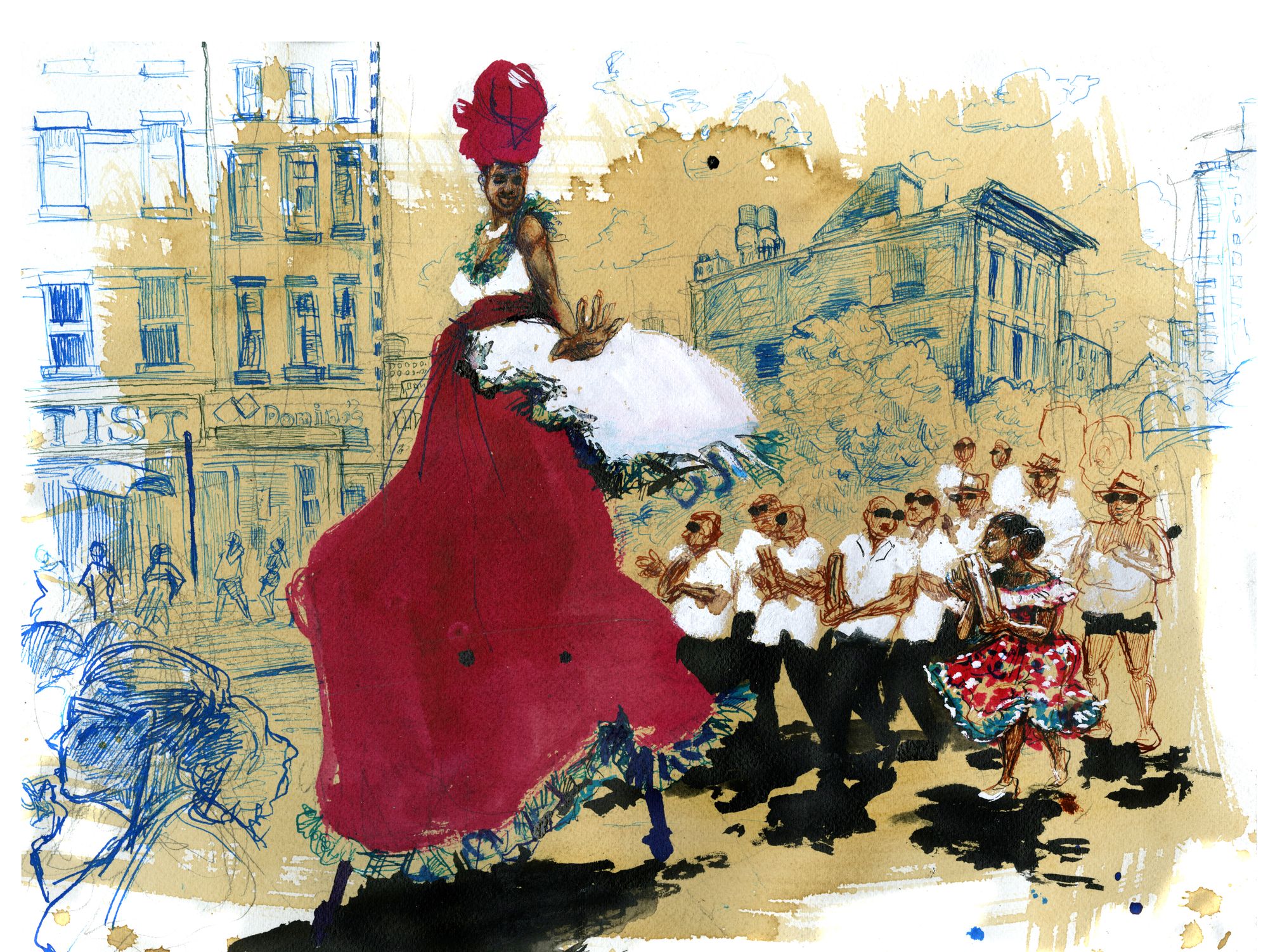

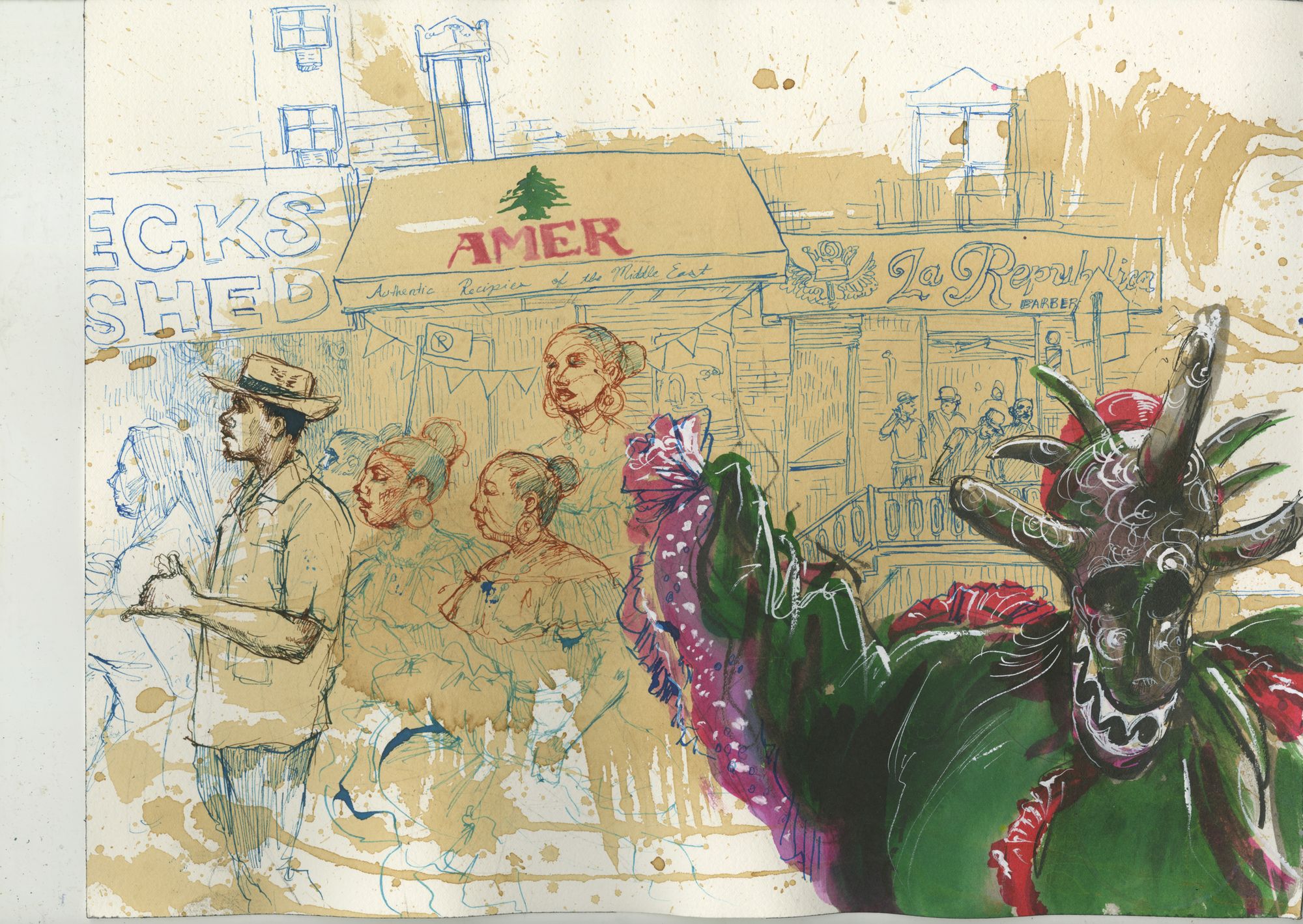

For 50 years here, on the weekend after July 25th, the statue of Santiago Matamoros—St. James the Moor Killer—was paraded through East Harlem for La Fiesta de Loiza. Here as in Loiza, the statue was so festooned with ribbons that Santiago's horse was nearly hidden. You couldn't make out the severed heads beneath the hooves. As for the knights, they had vanished. This is the vejigante’s day. Surrounded by stilt walkers, bomba dancers, piragua sellers and plena bands, the vejigantes capered. Their satin suits shimmered. Their masks were vivid with polka dots, pattern work, and the Puerto Rican flag. They danced through the streets of El Barrio as its heroes.

A saint born in the revanchist bloodlust of the Reconquista, defined in the genocidal conquest of the New World, appeared in front of a Lebanese restaurant, utterly stripped of his poison. The workers on break stopped to cheer. The story had been reshaped, without anyone issuing a single apology, or writing a single analytic text. This is art's power of subversion. It transforms the meaning without altering a word. El Barrio hosted its last Fiesta de Loiza in 2018––a victim of dwindling funds, the festival has since been replaced by a less religiously inflected event. I’m grateful to have drawn these sketches the year before the Fiesta, which is still going strong in Puerto Rico, went dark in New York. When I asked parade goers what the celebration meant to them, nearly all responded: “African pride.” ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast