Experimental Animation in the Pandemic Pause

The Eyeworks Festival of Experimental Animation, founded as a curatorial project in 2010 by artists Lilli Carré and Alexander Stewart, showcases abstract animation and unconventional character animation. As part of the ongoing partnership between Eyeworks and Pioneer Works, the festival has put together a special pandemic-themed program for Pioneer Works Broadcast, with three screenings scheduled on August 13th, 14th, and 16th. Pandemic Eyeworks includes a selection of historical and contemporary works that address feelings, situations, and circumstances that have arisen from the Covid-19 pandemic. The films touch on possibilities of contamination, fear of sickness, and the realities of boredom, loss, hope, and isolation. It starts with bats and ends with a cosmic and viral abstraction.

Jim Trainor, The Bats (1998)

This Pandemic Eyeworks starts off comically educational with The Bats, a film about the patient zero, the animal from which the contagion reportedly jumped to a human. The film is black and white, with line drawings that make it feel like animated doodles in the margin of a textbook or even cave drawings. The deadpan narration is both colorful and matter of fact. True to science, the bats live in different groups differentiated by their specific sonic pitches.

Animations are completely silent by nature. Nothing visual makes a sound because it’s all been drawn into the universe. The animator starts from the blindness of the blank page and uses his line to sort of echolocate, using vibrating lines just how the bat uses pitch frequencies, sound waves, to feel out the darkness. Trainor represents these sound waves with the same line weight that comprises the physical bats. At the end, the narrator reveals the year to be 1361, giving a little Dark Ages resonance to this cave environment, which also feels like the cavernous darkness of our own quarantined skulls. You can call me Joey Camus if you want to, but The Bats rejects existentialism through an absurd humanism.

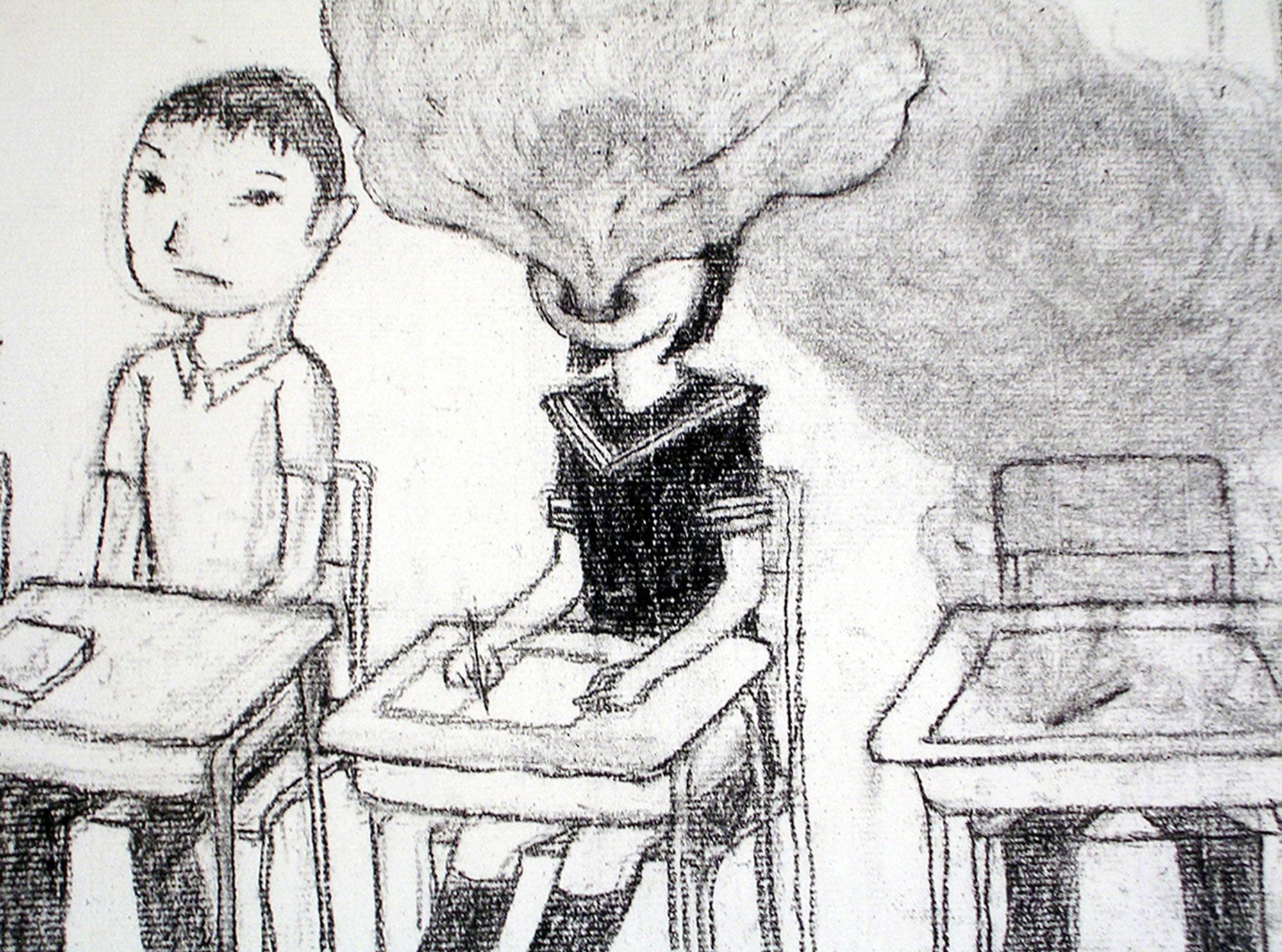

Naoyuki Tsuji, Looking at a Cloud (2005)

The first three films in this program are black and white, but unlike Trainor’s nervous doodles, Tsuji builds up the movement in each image through a pencil line and erasure. The subject of Looking at a Cloud feels immediately interpretable as pandemic-related. The film depicts an undefinable entity sweeping into the classroom and entering students through their nose and mouth. Though Tsuji’s style employs erasure-animation similar to an artist like William Kentridge, in Looking at a Cloud the erasure comprises the entity moving through the landscape. Tsuji becomes a figure himself, a mass of erasure hovering over the landscape looking for its next move.

Len Lye, Tusalava (1929)

There’s a miniaturization process that feels essential to filmmaking—that through lenses, images of the world are being trapped on inch-sized celluloid rectangles. Len Lye was an experimental cinema pioneer who eventually innovated a technique of washing and applying paint directly to blank negatives, to physically animate directly on film, similar to the work that Stan Brakhage would make decades later. Before this, however, Lye used traditional black and white drawing, and we seem to be watching Tusalava through a microscope. The name of the film comes from a Samoan word meaning “in the end, everything is just the same.” Combining the Modernism of the 20s with the patterns of tribal art in New Zealand, Lye divided the picture plane into vertical graphic zones, then indicated an organic, cellular-like movement that edges those borders. It feels like a biological intelligence, alien but organic. The wiggly results inoculate, contaminate, or even reproduce with each other. He would eventually call animation “an intuitive vision of antibodies and macrophages,” though he also referred to the wriggling worm as “a totem of a tribe near Alice Springs, NZ, that considers grubs to be the ancestors of human life.”

Adebukola Buki Bodunrin, Gather + Listen (2014)

This film is an example of how inclusion in the Pandemic Eyeworks program gives it a totally alternative reading. According to Bodunrin, Gather + Listen focuses on “subtle movements and rhythms that unconsciously happen at Owambe, a Nigerian street party.” Bodunrin loops the movement to use a type of infectious rhythm that emits the kind of warmth that draws you out into the street to mingle with strangers. The stains of color look like sweat or a little drip from a brightly colored drink. In 2020, seeing the film’s subtle hand movements floating around the screen and its mouths opening in a smile, feels like an upbeat PSA to “wash your hands.”

Yoriko Mizushiri, Maku (2014)

The goal of this writing isn’t to review each animation, but to provide a little room for thought about these films while making the case that there’s something particularly quarantine and Covid-19-related about the pursuit of experimental animation in general. That being said, the sensuality of Mizushiri’s lines, the way the limbs move, produces such a synesthetic touch perception that I felt emotionally moved during these shut-in times. When that eyeball floated in the diagnostic exam I thought the moral would be about testing, but it was the micro-moment of contamination, when the grains of sushi rice seductively fall into the head of beer, sinking into foam.

Sebastian Buerkner, Purple Grey (2006)

Pandemic-related anxiety feeds feelings of us being jettisoned from our social and work groups, and feeling ourselves more as an isolated protagonist. We are presented with an abundance of time, which we had always wanted more of; theoretically, this should result in a super-abundance of productivity. The pressure of being in a room, in front of a blank page in the middle of a pandemic, poses the question as if from a screaming tea kettle, “What matters?” In Buerkner’s Purple Grey, a computer graphic environment feels like the makings of film noir without a narrating voiceover, or more that we and the protagonist are stressed out, waiting for the narration to begin. All these little blips of the physical world take us from the tip of our pencil to the vectors of the moles on our digital skin. It’s an anxiety-provoking film that resonates more during quarantine, when we don’t have any interruptions except ourselves.

If you have any specific questions about my insights on other films in the program, find my email address, find my phone number. I will say that seeing Joshua Mosley’s film Jeu de Paume (2014) initially didn’t make sense. I had become so familiar with it from its excellent, subtle puppetry and camera movement that recreates a specific type of indoor tennis match, between two very identical-looking men in 1907. The spare audio, of foot scuffling and rackets hitting the ball, meant it took me a minute to associate it with that new Covid “normal” of playing sports without an audience.

Nicole Hewitt, In/Dividu (1999)

Even though all these movies deserve attention, I want to skip to the end, to say that these last two films curated in Pandemic Eyeworks have a certain material-spiritual resonance for me. Nicole Hewitt’s In/Dividu uses stop motion animation in the tradition of Jan Švankmajer, to imagine objects that have exploded not into a useful diagram of their component parts, but into suspended rubble. To see these objects as figures, the action relates to the feeling of our own bodies exploding—or should I say expanding. It’s not normal debris, but the volume of a single object blown into bits.

By end of the film, under the sound of a dial-up modem, Hewitt turns the camera towards the skin. Each epidermis filling the frame in succession turns into piecemeal, and the film becomes a body in bits. The whole film struck me as very “indoor”-feeling, quarantine related. In/Dividu was made right after the war, and the animated objects lend a feeling of trauma being processed. The “indoor” feeling I mentioned above is related to the uncanny historical moment when Croatians could maintain a certain type of stressful normalcy through the duration of the war. The pent-up energy feels like an artist in hiding. All of the fishing wires on each piece of that exploded chair feels uncomfortable. Should we notice it? Or is it an invisible armature meant to be politely ignored? Then we are left with just the mess of fishing line.

Hewitt wants us to see the strings. If I were a theoretical physicist I would talk more about them as a charged mass, a vibrational space that reminds us of not the microscopically invisible, but the quantum states that surround our dimensional bodies with Time.

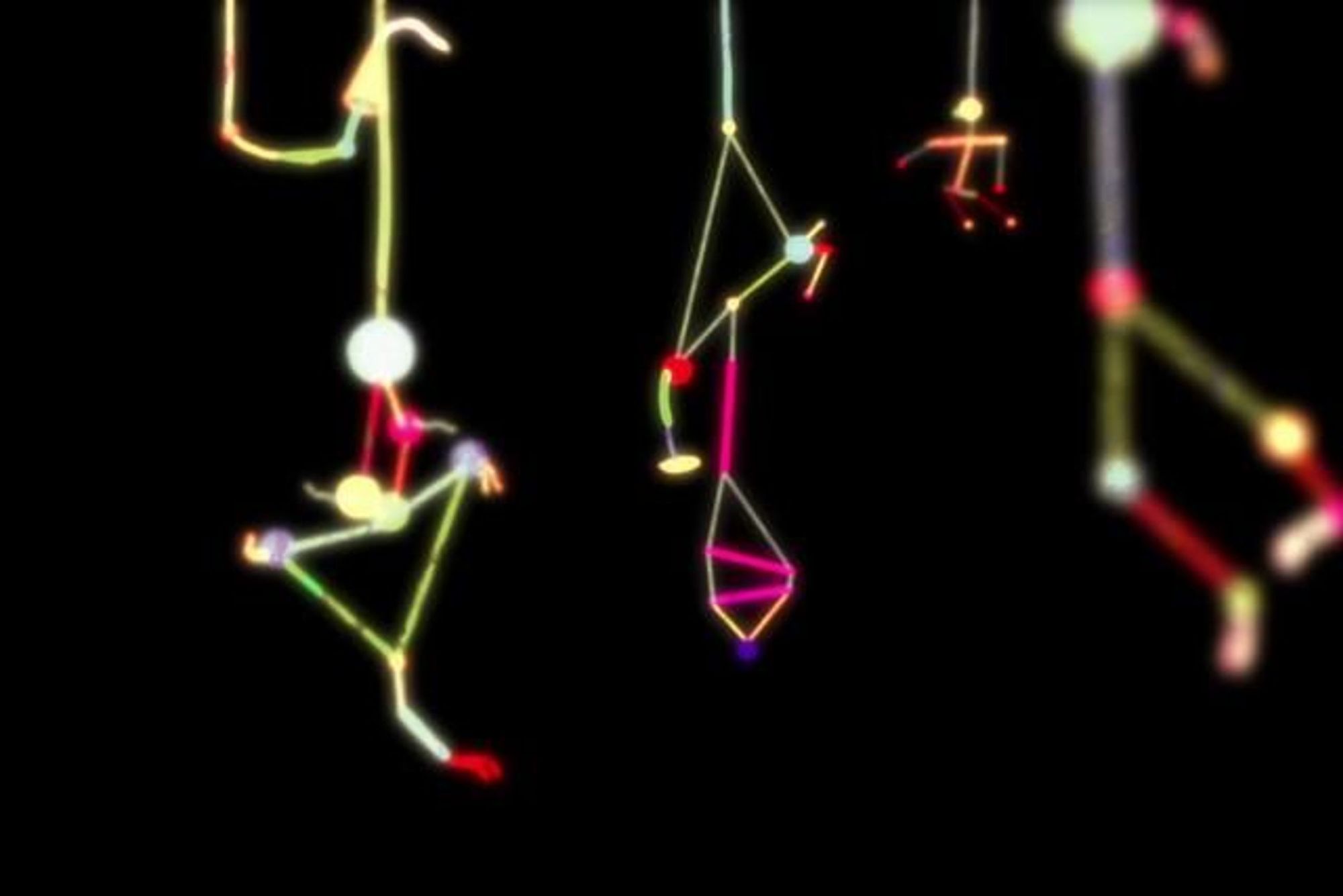

Caleb Wood, Mobile (2012)

This final work moved me—the way the drawing in Caleb Wood’s animation glows in darkness, the spheres and cosmos depicting a life both static and reborn again through an unknowable God. It’s like slack physics, a physics of loose strings. The strings here are entirely different from the stop motion In/Dividu. Wood explores an animating strategy with fixed points and wobbly connecting lines. The planetary Mobile has a feeling of the Universe in rebirth, while seeming to almost be a rotoscope of an actual mobile recently taken down from above a baby’s crib. And in this glowing darkness, all those faint chirping frog sounds are a regenerative volume, an unexploded space.

Subscribe to Broadcast