The Art of Decolonization

Anna Tsouhlarakis, The Native Guide Project: STL.

Photo: Jon GitchoffOn a cold, sunny day in October 2022, two artists and a curator sat down in Joan Heckenberg’s kitchen and offered to buy her house. Heckenberg’s one-story, white clapboard home looks modest from the street, but its backyard has a wide view of the Mississippi River. The artists, Jackson Polys and Zack Khalil, had flown into St. Louis to visit her twice before. The curator, James McAnally, dropped by so regularly that he sometimes helped out around the house. At this point, they had all gotten to know each other. The previous day, Polys had brought Heckenberg a jar of salmonberry jam from his family home in Alaska. Today, they brought her a cash offer of $160,000.

Heckenberg, a retired nurse in her mid-eighties, is used to receiving all kinds of visitors because she lives on what remains of a thousand-year-old sacred Indigenous site called Sugarloaf Mound. The Osage Nation has been working to regain ownership of the land for well over a decade. In 2009, the tribe purchased a third of it with their funds, when the family who owned the bungalow atop the mound, just uphill from Joan, was ready to leave. Heckenberg has since been one of two remaining holdouts; the downhill property belongs to the Kappa Psi fraternity, associated with St. Louis’s University of Health Sciences and Pharmacy. Over the years she has suggested that she plans to bequeath the land to the Osage in her will, but she has also mentioned a nephew who would like to inherit the house. At various points, the Osage have floated the idea of a sale, but Heckenberg hasn’t wanted to leave her lifelong home.

In the course of their October visit, Polys, Khalil, and McAnally explained to Heckenberg that if she sold now, she wouldn’t need to move out immediately—or at all. They explained how this could be arranged. As core members of the group New Red Order, Polys and Khalil have spent years documenting Land Back cases around the country, interviewing people about the various, often ad hoc, ways that such transfers are made. One precedent for their current negotiation occurred in 2015, when a man named Bill Richardson decided to sell seven hundred acres of land on the California coast to the Pomo Tribe. The city of Oakland engineered a novel contract ensuring that he can continue living in his family home until his death, even though he technically doesn't own it anymore.

Land transfers to Indigenous groups, whether as gifts, sales, or bequeathments from individuals or institutions, are increasingly common in the United States, although they don’t often make national headlines. In 2019, Eureka, a town in northern California, returned a two-hundred-acre island to the Wiyot Tribe, which had been seized from their ancestors during an 1860 massacre. In 2020, the nonprofit Conservation Fund bought twenty-eight thousand acres in Minnesota on behalf of the Ojibwe. As far as art institutions go, the best-known example is that of Yale Union, a contemporary art space in Portland, Oregon, whose board gave its building and land to the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation in 2020. McAnally and New Red Order were building on these successes, and had received a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to support the return of Sugarloaf.

These efforts—often called rematriation to avoid the etymological baggage of the patriarchy—tend to involve years of negotiation. “The legal structure of America is set up to make it really hard to give land back to Indian people, and there’s no clear way to do it,” Zack Khalil explained to me. The movement for territorial sovereignty has loosely coalesced under the term Land Back, but it remains decentralized. Collecting and comparing stories makes the process easier each time, sparing people on both sides of land transfers (the artists have called them “Give It Backers”) from “reinventing the wheel every time.” And yet the circumstances here were somewhat unprecedented: artists were helping broker a significant rematriation project, in the context of a contemporary art triennial, backed by a private foundation.

And it appeared to be working. After a decade of wavering, Heckenberg seemed to be making peace with the idea of a sale, and even moving out, too. Everyone in the room was emotional. “In this surreal conversation,” McAnally said, “she was very much talking in the past tense, as if she had decided to leave. There was this whole performance of this is the ending.” But then Heckenberg switched gears. She said she didn’t want to leave until her elderly dog died. She added that she might want to bury the dog on the mound. “And then with this little wink,” McAnally recounted, she said: “I don’t think the Indians would be too happy about that.” The off-kilter comment was in keeping with her sense of humor, and they left cautiously hopeful. They’d give her some space for a while, and then they’d come back.

***

Between 800 and 1600 AD, this area was home to the largest pre-colonial settlement north of what is now Mexico. Here, at the intersection of the Mississippi, Missouri, and Illinois rivers, the Mississippian civilization presided over a thriving hub of trade and agriculture. These groups constructed dozens of what are now called platform mounds, impressive earthworks that were used for various purposes: ceremonies, astronomical observations, residences, burials, and sending signals, such as fire signals, over long distances.

Several tribes, related by the Dhegiha Siouan language group, were living among the mounds when, in the 1670s, French explorers started to float down the rivers in canoes. We know who was living there in part because the French wrote the tribes’ names on maps and documents: the Osage, Ponca, Quapaw, Omaha, and Kaw. Soon, French, Spanish, and British settlers caught on; this was a great place to live. In 1682, a fur trader decided that the area would now be part of France. He named it La Louisiane.

In their foundational text “Decolonization is not a metaphor,” which has become a touchstone for Land Back movements in the United States and beyond, Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang describe the particular form of violence that followed first contact in the Americas. “Settler colonialism is different from other forms of colonialism,” they write, “in that settlers come with the intention of making a new home on the land… Land is what is most valuable, contested, required. This is both because the settlers make Indigenous land their new home and source of capital, and also because the disruption of Indigenous relationships to land represents a profound epistemic, ontological, cosmological violence.”

In 1803, the newly formed United States bought a third of North America for $15 million in the Louisiana Purchase, and St. Louis became a crucial waypoint—dubbed “Mound City” and “the Gateway to the West.” For the next century the river basin was the heart of colonial expansion. It became a railway transit point, an expanding urban center, and home to the armories and weapons caches necessary to kill or displace all the people living in the “empty” territory west of the river.

Over the course of several waves of slaughter and displacement, settlers began to raze the mounds, flattening and parceling the landscape. In 1825 the Missouri Osage made a treaty with the United States government, forcing them to move to Kansas. In 1871, they were again relocated, this time to Oklahoma. From 1845 to 1909, native people were legally banned from living within the St. Louis region. Today there are no state or federally recognized tribes in Missouri.

Sugarloaf—named by the French because it reminded them of the cones they used to transport sugar—is the last remaining mound on the Missouri side of the river. On the Illinois side, the Cahokia Mound complex stands relatively well preserved. Furred with mown grass, it is open to visitors, who can see what the mound may have looked like a thousand years ago through an augmented reality app. The area was declared a UNESCO heritage site in 1982.

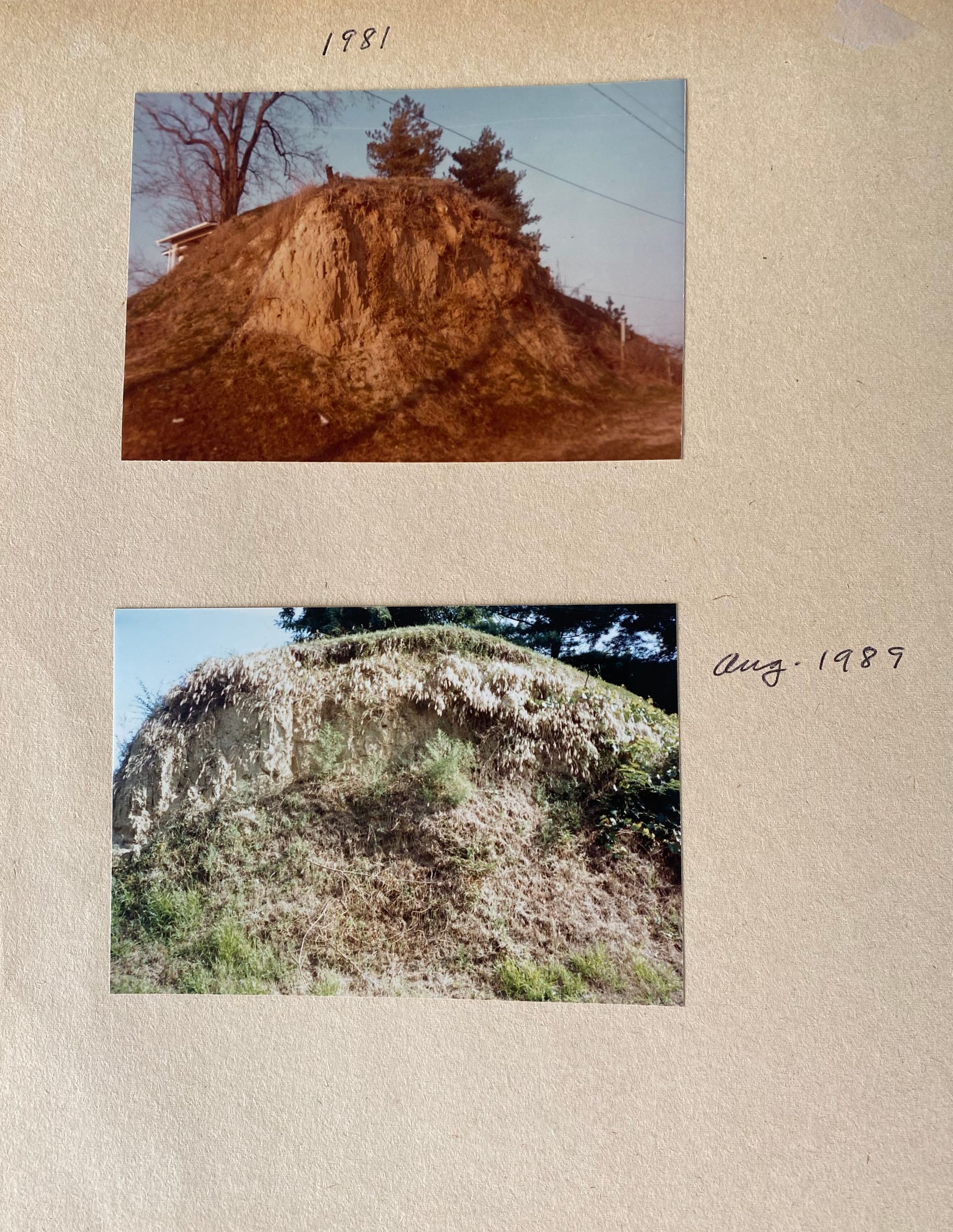

Sugarloaf has only survived this long thanks to a string of historical accidents. In the nineteenth century it was damaged by a quarry near its south side, and at some point a chunk of the mound was carved away for a dirt road. In the 1920s, families started settling on the still-stable parts of the mound, building three houses from its highest point to its lowest tier. Heckenberg’s grandparents built a house on the middle plateau and she moved in with her parents when she was about five years old. In the 1960s, the I-55 interstate was planned, and would have cut directly across Sugarloaf—but then a land survey showed that mining had made the ground unstable, and the highway was nudged three hundred feet away, incidentally sparing the houses. With some brief gaps, Heckenberg has lived in the middle house for eighty years.

***

Recruiting settlers like Heckenberg to just “give it back” is central to New Red Order’s art practice. Founding members Jackson Polys, Zack Khalil, and Zack’s older brother Adam Khalil sometimes call themselves a “public secret society.” Their name is a sardonic reference to the Improved Order of Red Men, a still-existent fraternity first formed in 1813 (“whites only” until 1974) that claims lineage to the Sons of Liberty, who claimed responsibility for the Boston Tea Party. One of the artists’ longest-running projects is a recruitment campaign for “non-native informants”—corporate-style videos and a website advertising a working hotline that allows non-native callers to dial in, inform on settler culture, and join NRO. Their primary recruit, who has become something of a mascot, is veteran actor Jim Fletcher, a “reformed Native American impersonator,” who appeared in a 2015 Wooster Group performance in Indian costume. He now appears in NRO performances and videos delivering (deadpan, funny) apologies and invites others like him to “change your life by learning to recognize—and report on—the efforts of non-Indigenous people everywhere to claim indigeneity.”

The materials of the ongoing “Give It Back” campaign lampoon corporate aesthetics and feel-good lingo. NRO are emphatic about looking for “accomplices, not allies.” This vocabulary is drawn from a 2014 pamphlet by the collective Indigenous Action, and proposes that allyship of the lip-service “solidarity” type can exploit cultural signifiers to distract from the real terrain of struggle, or absolve people in power from making real material change. Accomplice-ship, meanwhile, is focused on direct action.

I went to college with the Khalils and have followed their work in the intervening years. In 2016, the brothers, who are Ojibwe from Michigan’s upper peninsula, made the film INAATE/SE/, a mix of documentary and wild fiction that imports an Ojibwe first-contact prophecy into the present day. Around that time, they met Polys, a Tlingit artist particularly well known for his carved sculptures, and over time the three of them started talking about how they felt that they had been conscripted into a “native informants’ role.” That is, they found themselves tasked with interpreting and sharing native cultures with largely white art audiences—extracting from their own lives and histories for show. In 2018 the three “inducted” themselves into New Red Order (although their “real induction,” Adam told me, happened in 1492). Their first piece together was a video about the “Kennewick Man,” a nine-thousand-year-old Indigenous human skeleton that the Colville Tribes spent twenty years petitioning to get back from the National Parks Service, the Army Corps of Engineers, and the Smithsonian Institute.

NRO’s increasing notoriety is due to several expansive projects in sites far outside the museum, with collaborators far beyond the art world. For their largest work to date, a 2023 Creative Time commission, they flipped the classic colonial World’s Fair model and built The World’s UnFair in an empty lot in Long Island City. In the center of the weedy lot, a goofy, disconcerting animatronic tree spoke with a goofy, disconcerting animatronic beaver about the history of private property (Dexter and Sinister, 2023); a five-channel video installation broadcast Jim Fletcher’s exhortations (Give It Back, 2023); and a stage hosted revolving conversations and performances. NRO’s projects often seem deceptively ad hoc or casual, when they are the result of intensive research, organizing, and recruiting. Asked about this playful approach, the Khalils refer to the “trickster element” of the Ojibwe cultural tradition.

When Adam Khalil—holding a red Solo cup and wearing his signature NRO-branded wide-brim cap—first mentioned the Sugarloaf project to me in fall 2022, I was not surprised by the scale of ambition. NRO has long insisted that art-world resources can be leveraged for material change rather than symbolic statements. At one point, they approached curators at the Whitney and asked whether the museum would consider handing over its Met Breuer building to an Indigenous collective. (In 2023 the Whitney sold it to Sotheby’s instead.) But I was surprised that Mellon had offered money for a Land Back cause—major funders can be skittish about involvement with such initiatives because of their sensitive nature—and impressed that NRO had made such a leap across the provocation-action divide. It’s one thing to run a tongue-in-cheek “Give It Back” campaign. It’s another to secure hundreds of thousands of dollars to get it back.

***

James McAnally, the initiator of the renewed Sugarloaf effort, never intended to start a big triennial. “The formation of institutions is what’s interesting to me,” he told me in a conversation at my kitchen table. It was only after trying lots of other models aimed at bringing art people and everyone else together that he ended up starting Counterpublic. His reluctance was overcome by his sense of what such a structure—compromised, flawed—could achieve. He continually calls Counterpublic “a container,” “an instrument,” and “a tool.”

Everyone hates, or claims to hate, the -ennial model. If you read art magazines, you know that a large percentage of reviews of these periodic events begin with a cursory paragraph about how fucked up the premise is (I have written such paragraphs myself). The problem, writers point out, is that biennials and triennials tend to be temporary, extractive, apolitical interventions into local landscapes with little regard for what’s already happening there. Curators are usually imported from elsewhere; the squad is assembled based on international pedigree rather than area knowledge; and the main audience is the international press. At their worst, these events function as shopping malls masquerading as critical interventions, like tiny Olympic games that the general public doesn’t care about.

Counterpublic, on the other hand, grew out of a highly localized DIY scene and was aimed at long-term engagement. McAnally, an artist, musician, and writer from Mississippi who moved to St. Louis for college and afterward ran a popular art space called The Luminary, launched the progenitor of Counterpublic in 2018—an exhibition across a neighborhood whose venues included a barbershop, a Buddhist temple, and a taqueria. The project grew naturally from the following year’s twenty-four-site show, which the curators called “a triennial scaled to a neighborhood,” to 2023’s three-month exhibition sprawling across thirteen neighborhoods.

More than half of the Counterpublic budget was given to people, groups, and institutions in St. Louis. “We were not trying to build up our own capacities or build this endowment kind of focus,” McAnally said. “My question was how to make concrete change.” A large portion went to the Griot Museum of Black History, some to the more recent George B. Vashon Museum of African American History. One artist, Maya Stovall, decided to give part of her project budget away as an act of reparation, in an undocumented piece called Theorem, no. 3, which preserves “the trust and anonymity of participants in no-strings transmissions of the official currency of the United States of America.” Counterpublic commissioned thirty-seven artworks, some of them permanent. One was a monumental public sculpture by Damon Davis that memorialized Mill Creek Valley, a central neighborhood of twenty thousand residents, mostly Black, who were displaced when the entire area was razed in 1959.

For years, McAnally had wanted to do a project involving Sugarloaf, and 2023’s Counterpublic helped him amass the necessary infrastructure. Counterpublic brought in Risa Puleo, a contemporary art curator and art historian of Mississippian cultures, who laid the ethical groundwork for approaching the mound. The two wrote a letter to the Osage Nation Historic Preservation Office asking to use the mound as a central exhibition site. They pledged a “high profile opportunity for community engagement”; to push for “civic action”; and to “materially support” the land transfer. Once the Osage’s cultural advisers replied with a go-ahead, McAnally enlisted NRO as participating artists and curators. Zack Khalil and Jackson Polys began making trips to St. Louis—Adam Khalil was abroad—researching the area, communicating with Osage preservation officers, driving to Heckenberg’s house and ringing the bell at her gate. “Initially,” Zack described their attitude going in, “there was an understanding that Joan wanted to give the land back.” But “it became apparent through speaking with her that it wasn’t clear a transfer was happening, so that changed the dynamic of the conversation.”

“It came down to money at some point,” said McAnally of the dialogue with Heckenberg. When the Mellon Foundation invited him to submit a project grant for Counterpublic, rematriating Sugarloaf was included as a line item in the budget. They received a $2 million grant to support the civic exhibition, with $350,000 earmarked solely for the mound. The funds were contextualized within the framework of monument protection. Monument protection is one way to repurpose an existing tool, which is often used for heritage preservation and nature conservation, and might be seen as a productively roundabout way to advance Land Back efforts like Sugarloaf.

At that point McAnally, Polys, and Khalil were able to visit Heckenberg with their $160,000 offer, based on a rough appraisal of her house. In a letter McAnally brought her that day, he clarified: “What this means for you is that we would be able to compensate you for the transfer of your home… Like you, we agree that this is the right thing to do for all involved, and have an urgency to complete this process.”

At no point, Khalil and Polys both emphasize, has anyone pushed Heckenberg to leave. Polys explained that if there was any element of coercion, “it could have been us who are doing the dispossessing. We don’t want that. We want to allow for a different kind of model and relationship building.” This was to say that Heckenberg, too, could at any moment accept the invitation to become an accomplice.

***

St. Louisans, if they know about the mound at all, are largely unaware that it has not been fully rematriated. The city flaunts Sugarloaf as a success story. A wall text introducing the main exhibition at the Museum of the Gateway Arch proudly announces that “the Osage nation owns and preserves Sugarloaf.” The Counterpublic cohort has worked to revise this misconception. For the 2023 exhibition, they replaced the advertisements on either side of the billboard adjacent to Sugarloaf, which usually advertise a weed dispensary and a personal injury lawyer, with two artworks by NRO and the Navajo-Creek artist Anna Tsouhlarakis. The NRO sign, which faces Heckenburg’s house, announces in colorful, cartoonish lettering: “THIS BILLBOARD IS ON SACRED LAND,” “GIVE IT BACK,” and “NEVER SETTLE,” over a painting of an idyllic landscape with a mound-like earthwork, and a house that looks a little like Heckenberg’s. Tsouhlarakis’s black-and-white sign reads: “WHEN / YOU LISTEN / THE LAND SPEAKS.” At the base of the mound, near where the quarry used to be, Osage artist Anita Fields installed forty wooden platforms resembling those used at Osage events today to create a gathering place, resulting from curator Puleo's invitation to members of the Osage to engage with the site.

New Red Order, Give it Back: Stage Theory.

Photo: Jon GitchoffMcAnally has been urging city officials for years to consider supporting the transfer in a public statement. When I asked him what a city could do besides proclaiming solidarity, he pointed out the obvious: a municipality can use eminent domain to seize any property it deems culturally or economically significant. I had forgotten that transfer could be so straightforward—and that the personal (what Heckenberg does with her house) is always structural (she’s there because laws defend her right to be there). At this point I understood the power of NRO’s tagline: anyone who is not Indigenous to this continent, who owns a piece of this continent, can voluntarily give it back.

But even when land is given rather than sold, it often has to be valued first. Priceless heritage must be priced so that it can change hands and be converted to something like pricelessness. The language of property has a way of obfuscating what’s really at stake: sovereignty—the kind of sovereignty that operates completely beyond property deeds registered with the United States government.

***

Driving south on I-55 from central St. Louis, you probably wouldn’t notice the mound. The forty-foot-high bluff is barely visible from the raised highway running alongside it. I wouldn’t have known where to turn if I hadn’t seen the enormous billboard rising up across the lanes. I traveled to Counterpublic during its July 2023 closing weekend, and after reading and hearing so much about the mound, I was surprised by how small it looked—just a grassy hill, really. A roughly paved road called Ohio Avenue leads from the highway turnoff to the two remaining houses. A chain-link fence designates the rematriated area at the top. Just below the ridge is Heckenberg’s unassuming slat house, her front porch decked out with folding chairs.

By then, I was frustrated by how outsized a part of this story Heckenberg had become. I had become slightly obsessed with her, and was angry at myself for being obsessed with her. I wanted to write about the role of artists and cultural institutions in making material change, and the hard work of decolonizing a continent piece by piece—and here I was, pursuing an octogenarian with a case of main character syndrome. At the same time, she was a person, not a character, and I didn’t want to let her flatten into one in my mind.

I didn’t have an appointment, but I had heard that she was usually home and liked visitors. I tentatively rang the bell tied onto her chained gate until she emerged from the house, wearing loose pajamas with paint smears. She didn’t look surprised to see me. “I’m painting some of the basement walls,” she said, gesturing to her clothes. She asked what I wanted to discuss with her, although it was obvious. I wanted what everyone wanted: to ask about her house. A breeze lifted a fluff of white hair from her forehead, and a little dog ran out from behind her, also fluffed with white hair. “I can talk to you for a little bit,” she said casually. I stayed for two hours.

Heckenberg was kind. She invited me to sit on her front porch and offered a soda. She is thin but not frail, although she complained that her whole body is “eroding, just like” the cliff behind her house. Trucks whizzed by constantly on the highway just across the road, shaking the pavement beneath my feet. Her yard was mowed and a little Virgin Mary statuette was planted near the front fence. She told me someone else now tends to her lawn, because the last time she did it herself it looked like it had a “Mohawk haircut.”

Her memory is extremely sharp. She can describe what’s happened on the mound in detail—always mentioning people by their first names as if I knew who they were, in the same confusing way that my own grandmother used to. She told me that as a child, she’d “played cowboys” up on the hill where the house of her neighbors, the Strosnider family, used to be. Back then, she and her parents thought they were living on a burial mound, but now she knows it’s probably a signal mound. In 2015, Dr. Andrea Hunter, an archaeologist who directs the Osage Nation Historic Preservation Office—who also led the task force to rematriate the first third of the mound back in 2010—brought a team to investigate the soil. They did remote sensing using a radar device that Heckenberg said “looks like a golf cart,” and found no evidence of human remains or artifacts.

She brought out her family scrapbook to show me her mother’s collection of photographs and newspaper clippings, which she’s added to. The pieces are lovingly assembled and annotated with descriptions and dates—“my front yard” or “the old quarry.” There’s a letter from the Missouri Department of Natural Resources thanking Heckenberg for her “efforts toward the preservation of this significant historic site,” upon Sugarloaf’s designation entry into the National Registry of Historic Places in 1984. There’s a page with cut-out drawings of the family of Sauk chief Keokuk, who was born around 1780 about 150 miles north along the Illinois River. There are pictures of a nearby workhouse before it was torn down in the ’50s. Heckenberg explained that the foundations of her house were built by prisoners who lived in the workhouse.

Sugarloaf scrapbook, courtesy of Joan Heckenberg.

Photo: Elvia Wilk

Sugarloaf scrapbook, courtesy of Joan Heckenberg.

Photo: Elvia Wilk

Sugarloaf scrapbook, courtesy of Joan Heckenberg.

Photo: Elvia Wilk

Sugarloaf scrapbook, courtesy of Joan Heckenberg.

Photo: Elvia WilkAbout half of our conversation was preoccupied, not with the Osage or Counterpublic, but with the “hobos and transients,” “hookers and homeless people,” who often travel over or stay on the mound. The mound is cut off from the city by the highway and its backyard overlooks train tracks by the river; it’s hardly well protected. For years, a mentally ill man squatted in the frat house down the hill with two pitbulls; he stole her mail, went through her trash, and threatened her. She joked that her dog, Molly, who is seventeen years old and blind, isn’t much of a guard dog anymore. The way Heckenberg tells it, living alone and vulnerable, armed with prayers and a gun, is stressful and frightening. Finally, she said with relief, the frat has lent the ramshackle home to a Palestinian man, who’s agreed to fix it up and keep squatters away in exchange for free rent. (I didn’t knock on his door due to the large sign saying “TRESPASSERS WILL BE SHOT.”)

Zack Khalil told me that Heckenberg’s preoccupation with her safety is one reason why they thought she might want to move. “She’s pretty isolated up there,” he said. “It’s like, okay, is there some way that we can help this person? It seems like kind of a win-win situation.” At one point, Counterpublic helped Joan tour condominiums that she could afford with the purchase money, but she didn’t like them. “I don’t want to buy a house,” she said to me. “I’m too old. See, when you’re young, that’s fun. You pick out your drapes, what color you want the walls painted. When you’re eighty-five years old… I don’t want to redecorate.”

I asked her in just about every way I could think of whether she believed that native people were entitled to the land. She’d say things like: “Oh, absolutely. Yeah. Oh, sure.” She worked in conditionals—what would or should happen. Sometimes she pressed fast forward to what will happen without explaining how it will come to be, or talked in past tense as if a handover had already happened. I remembered something McAnally had said about her way of speaking: “At first it was kind of like a quirk of her personality… and then it became clear that it was a strategy. She’s very savvy.”

“I am not moving until this dog’s gone,” she said, her voice rising with frustration, in protest against someone not there. “I am not standing in January in the freezing rain with an umbrella at three in the morning waiting for a dog to go to the bathroom. I see people do that. Yeah, I have seen people in terrible weather, older people standing with the umbrella for the dog to move its bowels, which sometimes takes a little while. I’m not doing that at my age, I let her out three in the morning. She goes out a lot at night. She’s old. When you get old, you gotta go to the bathroom a lot. She goes out, she pees, she comes back in, we go back to bed. I don't have to put shoes on, and a coat and gloves. I’m not doing that at my age. When she’s gone, we’ll take it from there.”

Many dogs have lived on the mound. The Strosniders used to breed Dobermans, Heckenberg reminisced, and when Dr. Hunter’s team did a ground study, she warned them not to mistake the canine skeletons for human remains. I asked her whether she thought burying dogs there might be upsetting to the Osage. She said she supposed so, because “the Indians don’t think much of dogs. If they called you a dog, that was an insult. That’s like if I called you a pig or a snake. So I thought, well, I better tell them. Yeah, cause there’s at least six Dobermans here.”

Before leaving Heckenberg’s house, I pointed up at the billboard designed by NRO, which she can read from her yard. “THIS BILLBOARD IS ON SACRED LAND. GIVE IT BACK.” I asked her what it was like to see the sign all the time. She shrugged as if she didn’t know what I was asking, and said it was awfully bright at night.

***

At the end of 2022, with Heckenberg continuing to prevaricate, Counterpublic reconsidered the Kappa Psi property, a brick duplex and garage built in 1968 and acquired by the fraternity in the ’90s. Frat bros used to live and party here, but Kappa Psi—“the oldest and largest pharmaceutical fraternity,” says their website—has left the home vacant for many years, seemingly disinterested in its upkeep. Neither members nor alumni have been remotely interested in dialogue with the Osage, much less contemporary artists. Early on in the curatorial process, McAnally said, “We approached them first as an arts organization saying, we are looking at this property for an art project. Full stop. That got us a response at first, but it didn’t lead anywhere.”

With funds from the Mellon Foundation in hand, they could make a formal offer on the frat property as well. The house was officially appraised at $175,000, and Counterpublic tried offering $160,000, then raised it twice, ending up at $220,000. “Their only response to date is that they want us to buy them condos closer to the college campus,” McAnally told me, “and that would cost like $400,000.” When I spoke with Dr. Hunter, she said, “To be honest with you, I just don’t get it. They’ve been flat out rude to us.” Heckenberg told me that she is also baffled about the frat’s refusal to consider the sale: “It used to be such a nice house. They could have sold it to ordinary people.”

The alumni of the frat may be stonewalling because they know Indigenous land is worth more than it’s worth. In 2021, the beer-making Busch family (net worth $17.6 billion) decided to sell a piece of their property about sixty miles west of St. Louis. The property includes an underground rock art site known as Picture Cave, with about three hundred magnificently preserved Mississippian paintings from a thousand years ago. Finally, here was an opportunity to buy it back; the Osage negotiated with the Busch family for months. “The more we talked about it, the price kept going higher,” Dr. Hunter told me. “They knew the importance of this cave and the artwork that’s in it. We kept having to go back to our Osage Nation congress asking for money, and then they got impatient and said they were tired of waiting on us to get the funds and they were going to auction.” The site eventually sold at auction to Morning Star and His Friends LLC, a Nashville-based company with two unnamed members and a law firm as its address. Nobody has been able to figure out who owns the company—or the cave.

***

When I first called Dr. Hunter in September 2023, she was wary. “Why are you writing this?” she asked. She asked me to tell her about my experience with tribes and to explain what I knew about the Osage. It’s clear that rematriation is extremely sensitive, but I wasn’t sure exactly what she was so guarded about—until she told me what types of cold calls she typically fields. There are “people calling us and wanting me to come look at their property because they think they’ve got a pyramid buried in their property that’s glowing,” and “people wanting to do a movie about aliens and one of them is going to be an Osage that crashes on our reservation.”

At the outset, I gathered that she had regarded Counterpublic's first outreach with similar wariness. “I thought this is crazy, what do artists have to do in our business? I really wasn’t thrilled about it in the beginning. People have odd interpretations of tribal people and there is such a huge lack of information and misinformation about tribes.” But after several conversations, Dr. Hunter's team invited Counterpublic to submit a letter outlining their proposed work with Sugarloaf, and in turn, tribal leaders unanimously agreed. Since then, Counterpublic has submitted all artwork and writing regarding the mound to the Osage for review before acting.

Most Osage revenue comes from the casinos on their reservation, and requesting funds for rematriation of any kind goes through a formal congressional procedure that can take longer than, say, the Busch family is willing to wait. Allowing the triennial to act as a go-between seemed like it could speed things up. “I thought, all right, fine, I’ll respond to them. So I just said, if you think you can help in getting Joan’s property and getting this fraternity’s property, have at it. We’ve been trying to do it for years with very little success. I figured it wouldn’t hurt to have them give it a try.”

To add a layer of complication, the question of whom to give land back to is not always so clear-cut. Waves of displacement over centuries mean that tribes have now lived for generations on land that wasn’t “originally” theirs. “Even though we’re removed from them, we’re not removed from them,” Dr. Hunter said. Further, the burden of proof is typically on tribes to demonstrate the facts of their own dispossession. Dr. Hunter and others have gathered evidence from oral histories and artifacts, to demonstrate the long presence of the Osage in the area. And still this makes no difference when private property is at auction: a seller can choose any buyer they want, as with Picture Cave—yet “another painful experience.”

She emphasized the uniqueness of Sugarloaf, explaining that the Osage mainly buy back land for their own reservation in Oklahoma rather than working out-of-state. The only reason they’d gotten involved with Sugarloaf was another chance cold call: back when the Strosniders living on the top of the mound wanted to sell their home in 2009, the Missouri state senator at the time, Ross Carnahan, had reached out—apparently he had a specific interest in native history.

At the end of our conversation, I asked whether this project had changed Dr. Hunter’s idea of art. She paused for a long time. “Not really. I really don’t give it a lot of thought.”

“At least you didn’t have to talk to Joan for a while,” I suggested, which made her chuckle. But then she said, “I need to pay Joan a visit.” At this point, they’ve known each other for over fifteen years.

***

Whenever I asked McAnally why he thinks curators and artists should try to do things like rematriate land, he replied with some variation of: “Well, whose job is it?” It’s not, he pointed out, like the arts are unbesmirched by histories of displacement and heritage destruction. Sixteen mounds were flattened to make way for the 1904 World’s Fair (“Louisiana Purchase Exposition”), including one of its central venues, the St. Louis Art Museum (which exhibited a new NRO video titled Give it Back: Stage Theory during Counterpublic’s 2023 run). By tackling Sugarloaf as a site for exhibition and for transfer, Counterpublic and NRO have pointed out how the history of art and the history of dispossession are often the same story.

American institutions have become accustomed to paying tribute to their own complicity with things like diversity initiatives and land acknowledgements. Over the past decade, in the general “arms race for land acknowledgments,” Polys said, these statements have become somewhat rote incantations. The noticeable uptick in exhibitions about social justice might help raise consciousness in certain audiences, but these projects can also pave over the hypocrisies that produce the problems they depict. An example of this contradiction that was mentioned to me twice while reporting this story is the 2020-2021 MoMA exhibition Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, which foregrounded the work of incarcerated artists, while protestors outside called for BlackRock CEO Larry Fink, the second largest shareholder of private prison companies, to step down from the museum’s board. The institution figures itself as the terrain of political struggle, which stops at its doors. As Adam Khalil put it in one magazine interview: “How do you ‘decolonize’ an institution? Well, practically speaking, you’d get rid of it.”

McAnally told me that “this kind of rising interest in art with a social conscience drives me insane, because most of the time it’s almost like using political language to launder money into the art world… It’s like taking things from community organizing or political organizing and moving it into an art sphere where it becomes symbolic and it loses some of its concrete force.” With Counterpublic, he wanted to run the code backwards.

Art that works in service of material change is sometimes described as a kind of “cover” or “mask” for the artists’ “real” agenda. I heard this reaction a few times during my reporting and found it curious, especially when it came from people who were familiar with the last century of what might broadly be called socially engaged art or relational art.

“If conceptual art and land art can be art, then giving it back can totally be art,” Adam said.

“It’s not art because it has utility?” Polys asked. “Such a silly idea.”

Zack pointed out that they wanted to “instrumentalize the resources that the art world has to offer,” but this is not some kind of trick. Nobody is being bamboozled: they’re being invited, and artistic integrity is not being denigrated. Polys added: “I love art too much for that. Art can just be the change.”

I mentioned that Dr. Hunter didn’t seem preoccupied with the art aspect of Sugarloaf’s rematriation. “It makes sense that for someone like Dr. Hunter or for many Indigenous people, contemporary art is irrelevant,” Polys said. I took this to mean that NRO’s intent is not to convince the Osage, or anyone, that art matters. It’s to make art, to leverage their industry to push rematriation forward, and in doing so to create new relationships. In what other situation would Dr. Hunter and McAnally and Heckenberg—and I—all be chatting?

*

I have found it hard to resist turning Heckenberg into a living embodiment of settler colonialism. It makes no sense to pin the blame for centuries of dispossession on one woman; yet rarely do you come face-to-face with someone who so perfectly encapsulates the contradictions and complexities of what it means to possess. I asked the three members of NRO how to reconcile my thoughts about her. Polys, who, at forty-seven, is a decade older than the Khalils, asked with a wry smile: “So this is the moment for simultaneous empathy and critique? And maybe a note of hope? I think, Zack, you’re going to do that, right?”

Zack smiled kindly. “I don’t know if Joan has to be ‘reconciled,’ so to speak.” He went on: “I think she also has a real intense interest to give it back. And I think she has a real intense interest to be at the center of a story too, as much as she seems like she doesn’t want to. It’s a lot of oscillating back and forth, in a way that’s troubling but, to have empathy, understandable. She grew up there, that’s the place that she knows as her home.” Yet, “for Joan, that’s a very personal conversation. It’s her legacy. It’s her land… It’s tied up with all these really intense, traumatic emotions—and such a huge amount of change—having to consider one’s own mortality, having to consider one’s own legacy.”

Polys agreed: “She encapsulates this idea of the personal and the structural, and that can be uncomfortable. And I think within that dynamic, she has a desire for recognition—of her stewardship, holding space and also, her trauma.” Although the Osage could not be more explicit that they want the mound to be sovereign tribal territory, at least Heckenberg hasn’t sold the land to a trucking company. Heckenberg understands herself to belong on, and to, the land. In Zack’s words: “Politically and personally, I think she’s also expressed a real desire for indigeneity herself. She really likes Indians, or the idea of Indians.”

That reminded me of something that Heckenberg told me in her yard that had unexpectedly moved me. “I’ve only been on this planet eighty-five years,” she said, pointing to the ground. “My life span is so short compared to how old this is,” this being Sugarloaf. While she could have been saying that her choices weren’t important in the scheme of things, I got the sense that she was underlining the way that her life is inextricably tied to the ancient mound, and the fact that she is part of its history—which is true.

***

Closing weekend's performance by The Wah.Zha.Zhe Puppet Theatre at Sugarloaf.

Photo: Tyler SmallOn the final Sunday of the triennial, a large audience gathered at the base of Sugarloaf to sit on Anita Fields’s platforms and watch a performance by the Wah.Zha.Zhe Puppet Theater, a troupe organized by Fields’s daughter, Welana, and her son, Nokosee, among other Osage community members invited by Puleo. People of all ages maneuvered huge papier-mâché elk and birds in a retelling of the Osage origin story. They played a recording of an elder speaking the Osage language, which the UNESCO World Atlas of Languages says is “not in use.” The heat and humidity were so oppressive that my dress was soaked with sweat. Several performers and audience members were visibly emotional. Heckenberg stopped by briefly on her way to church.

Counterpublic’s project statement calls it an exhibition working “towards generational change.” The Mellon Foundation grant to rematriate Sugarloaf expires after two years, in September 2024, so there’s a set timeline. McAnally, however, has said that when it comes to Sugarloaf, “There are no deadlines for this work. It’s human relationships and legal processes… We as an organization are committing long-term, until there are no further paths or until it’s done.”

Rematriation is not about essentializing native connections with the land. It is, Adam pointed out, not even always about the land—it’s just that land is the most “legible” way to conceive of sovereignty. The long-term relationships enabled and required by land transfer projects are what allow sovereignty to be constructed in new ways, with new accomplices. Emphasizing the slowness of this work, Zack said, “You have to move at the speed of trust. That’s been our relationship with Joan. Just having to show up over and over again. Call over and over again.”

And so, after a long pause, in the fall of 2023, McAnally and Dr. Hunter visited Heckenberg again for a chat, and by December, she had verbally agreed to a purchase option that would allow her to leave whenever she wants. This time she has agreed “with certainty,” reaffirming her decision twice. Counterpublic’s legal representative drafted an agreement that accords with the Mellon grant stipulations, and as of mid-February 2024, the document is now with the Osage, who are reviewing it closely before all parties present it to Heckenberg for a signature. The offer to purchase the Kappa Psi land still stands, should the fraternity choose to take them up on it.

“It might not feel like that at first, but there’s something to be gained for everybody by giving it back,” Zack told me. “It would be hard to deny that our country, our nation, the world, maybe, is on a path that’s fundamentally unsustainable. I’m not saying that native people are superhuman new age forest bunnies that are going to solve global warming in an instant. But there’s a reason we’re in this position right now.”

When he said this, I remembered Heckenberg’s odd use of verb tenses: what would happen or what will happen, with no mention of how things would get there. I realized that sometimes NRO does the opposite: they speak about the future in the present tense. As if it were already here. As if it were happening. Because, as Polys told me, “belief shapes reality.” Or, in Zack’s words, “the rematriation of all Indigenous land and life” is a slow process, but, grinning: “It’ll be reality before you know it.” ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast