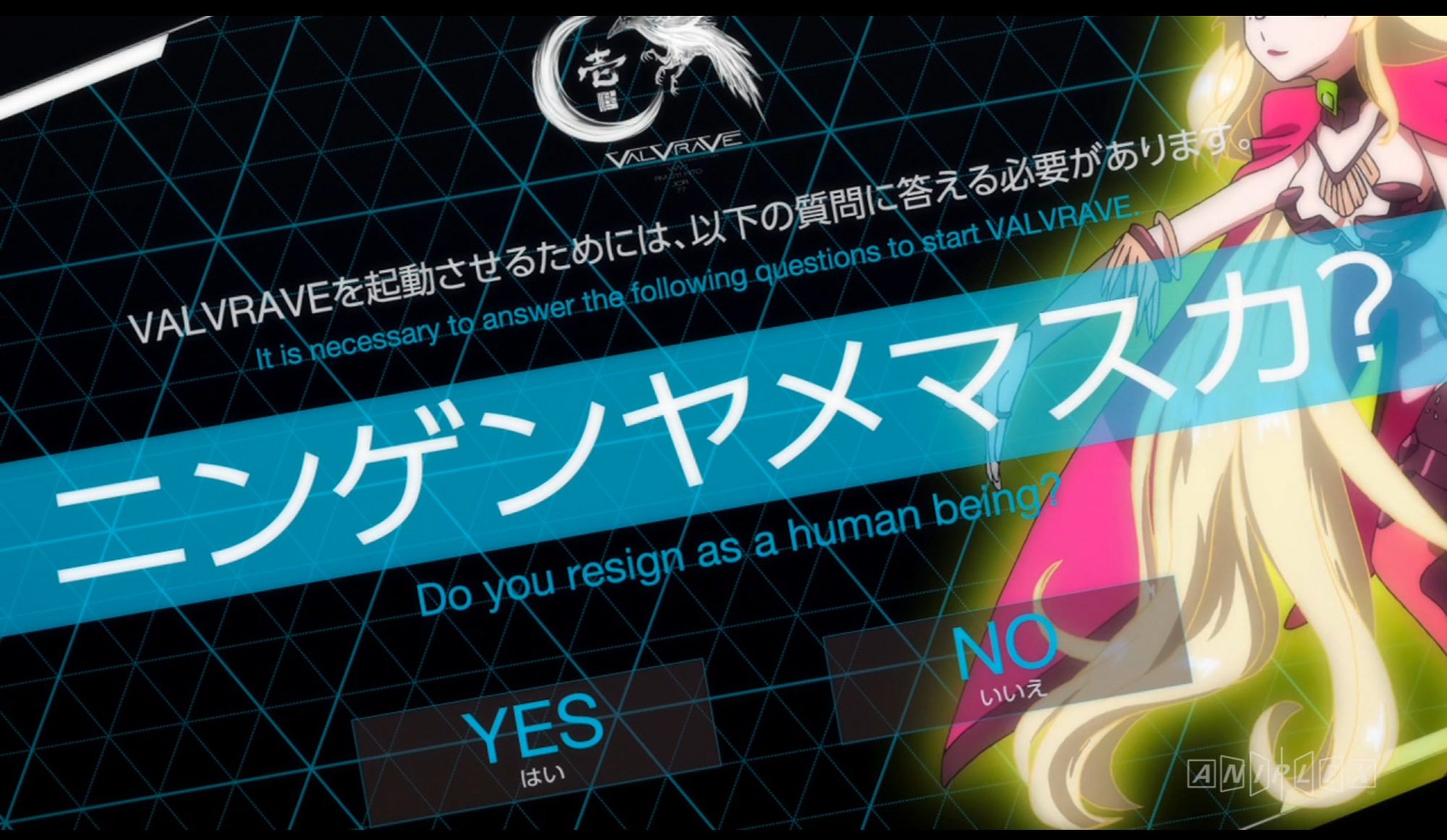

"Do You Resign as a Human Being?"

“O Diotima! Diotima! When shall we see one another again?”

Hyperion to Diotima, from Hyperion, or The Hermit in Greece, Volume I, Chapter LII

I.

"Shoko..."

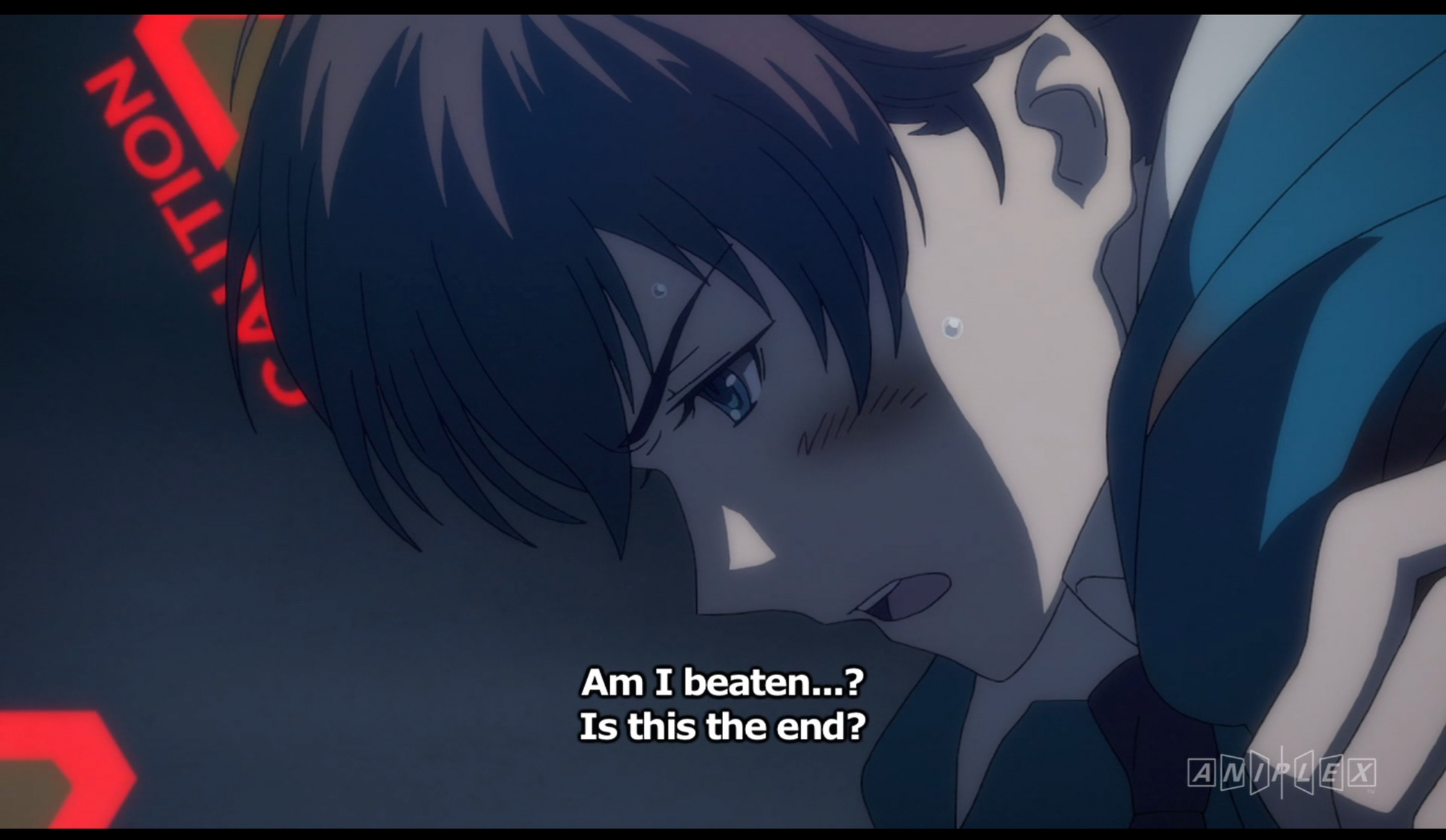

Haruto whimpers the name of his teen lover. He buries his face into his palms but cannot stop tears from streaming out of the gaps between his fingers. As he turns away from the feverish color of the skyline and the deafening sounds of explosions, a penetrating sensation occurs in his vertebrae. It’s time to forgo his wet dreams about Shoko: ever since he integrated into this war-machine, the colossal humanoid robot called Valvrave the Liberator, the corporeal possession that is neurocognitively linked to his emotions has caused him great pain.

II.

When the seventeen-year-old high schooler Haruto wakes up in the pilot’s seat, the world had become an unrecognizable place. We are watching the Japanese anime TV series Valvrave the Liberator (2013). Human beings were now in the Third Galactic Empire, where 70% of the population had immigrated to a terraformed space station constructed around an artificial sun, and were suffering under two mutually exclusive forces: the military superpower Dorssia and the trade oligarchy Atlantic Rim United States (ARUS). Jiro, Haruto’s home station, had been contested as the last neutral territory in between.

Produced by Ichirō Ōkouchi, Valvrave the Liberator originally received a moderate rating on bilibili.com, the hottest streaming platform in mainland China with a monthly viewership count of around nine million. The platform has also become known for its “bullet screen” feature—popular in websites in mainland China and Japan—where real-time comments shoot across the screen. As a predecessor of Mecha classics like Neon Genesis Evangelion or the Gundam series, Valvrave the Liberator, as high-caliber a production as it was with its young, delusional, chuunibyou-ish characters and eerily surreal plot, didn’t stand out in its genre. The anime even received a joking appellation as “Valvrave the Humiliator (for the spectator)” among its mainland fans for how far-out its plot seemed.

Somehow, this once-dustbinned anime’s fate took an unexpected turn six years after its premiere. On November 15th, 2019, it received a sudden flow of attention from 92,000 mainland viewers on bilibili.com, and the rating of the anime soared to 9.8/10, a sensational score for the streaming platform.

The striking coincidence between the anime’s plot and the political scene in Hong Kong had grabbed the attention of mainland China’s internet users. In November 2019, heated online discussions around Valvrave the Liberator quickly metastasized; mainland ideologues and trolls unleashed disparaging and reactionary assaults on dissenting Hong Kong protesters on bilibili.com’s bullet screen. This clash happened contiguously in IRL events and in Animation, Comics and Games (ACG) subculture online platforms, yet the levels of contrarianism lie deeper than cyber-mobbing and soapboxing.

The constitutional principle of “one country, two systems” had been established at the 1997 British handover of Hong Kong to China. The profound contradictions it posited, and the painful schizophrenia that it subsequently brought about, have inflicted countless social and cultural agitations. In the minds of many progressive liberal democrats, Hong Kong’s freedom has been shackled. Yet for many mainlanders, “one country, two systems” has been a fundamentally enfranchising policy for Hong Kong citizens. From this perspective, Hong Kong’s quest for democracy and independence seems hand-biting and family-breaking. Some even hold the conspiratorial view that the movement is orchestrated by local elites with personal interests in Western capitals: Hong Kong’s democratic movement should therefore either be violently terminated or cast aside.

The mainland audience saw the anime as a caricature of Hong Kong’s political scene. Jiro was a neutral state trapped between two superpowers. Beset by attacks from Dorssia and economic manipulation by ARUS, the populace in Jiro—mostly consisting of Sakimori Academy students—found themselves situated in a climate infiltrated by deceptions and coercions, and decided to break away from the overarching established order to set themselves free. This audience also projected their pro-nationalist stance: Jiro represented the unfilial, hydrocephalic nation of Hong Kong. Valvrave, the Transformer-like robot neurocognitively connected to and piloted by Haruto, was regarded as the symbol of Hong Kong’s postcolonial superego, the phallus of Western imperialism incarnated as local elitism. Shoko, the female protagonist who declared independence on behalf of Sakimori Academy students, became the vicious avatar of Hong Kong protest leaders, who are naive with grandiose delusions and excessive political entitlement. As the constitutional mother of Jiro Nation, she incites the student body to behave like anarchists, and impulsively steps down as a commander. Without leadership or direction, drunks, thieves, rapists, and criminals flourish and fuel Jiro to a meltdown.

In the show, the socially inept students of Jiro spend their post-independence life transgressing social contracts, robbing supermarkets, and establishing idolatry. Shoko also employs social media irresponsibly to amplify her messages, streaming the daily life of Jiro and turning it into a mere spectacle to enlist resources, funds, and draft a military. In the end, it is Jiro Nation’s incompetence in maintaining its electronic operations that causes the final collapse: an eight-minute shut down wherein the climate control facility goes awry and the internet disconnects, exposing the impossibility of Jiro to delink itself from the rest of the world’s infrastructure and infosphere. The vulnerability of Jiro’s students greatly entertained the mainlanders: when Jiro Nation fell apart (its entire operation lasts only a few episodes), the bullet screen became clouded with deeply sadistic, schadenfreude acclaim.

For those inside the Chinese Great Firewall, the determination of Hong Kongers to riot evoked feelings of jealousy, like that of a bitter sibling. While Hong Kong's revolutionary spirit may be deemed by some as naive, their ability to exercise this spirit is a privilege that was historically deprived and obliterated from the mainland. It can be hard to recognize what has put Hong Kongers into a deep state of desperation, leading them to head into the streets to expose their flesh and bones to police violence.

Maturity or delinquency? Bilibili.com has a fairly young viewership, and the political perceptions of those conducting the internet mobbing diverge from the realities of Hong Kong’s civil disobedience efforts. For these millennials who’ve grown up with a perennial ban on mass gatherings and exhaustive censorship and surveillance, the anime is narrating Hong Kong as a hyperrealistic, modern fable. In fact, nowadays in China, social issues and class conflicts are experienced in an atomized and individualized way, while collective action becomes distant and loaded memories of May 4th or June 4th a national taboo. Japan-imported ACG subculture serves as an epistemic bunker among the younger generations, where they satiate their emotional needs behind many levels of abstractions, behind heavy filters of video games and disproportioned characters in manga series. It is cathartic for them to assume Hong Kong contemporaries are being delusional and wishy-washy, and these mainlanders find relief in acting out online. What's underneath the mainlanders’ clenched-teeth cyber-mobbing are anchorless, transhuman nihilist feelings.

IV.

Too young to die. The quest for democracy is so traumatic, and neither the bodies on the street nor the anonymous IP addresses in bullet screens can propitiate change without real political agency. Ghosts will keep haunting the Queensway and Victoria parks in the form of howling wind, and “404 Error”, “Page Not Found” messages will pop up like erected tombstones. Though street protests and bullet screens are two major sites of contemporary political struggles, without systemic change they are what theorist Marc Augé calls nonplaces, or spaces of transience. What's left intact are irreconcilable and schizophrenic ideological power structures.

“Freedom! understand the word who can — it’s a profound word, Diotima. I’m so deeply beleaguered, so incredibly hurt, I’m without hope, without a goal, I’m utterly bereft of honour, and yet there’s a power within me, an indomitable something that sends sweet shudders through my bones whenever it stirs in me.” - Hyperion to Diotima [LI]

In one of the most famous scenes in the anime, quite early on in the series, Haruto—our timid and lustful protagonist who has been accidentally bestowed the extraordinary ability to pilot The Valvrave—is presented by the humanoid robot with a question. It is perplexing yet unthinkable: “Do you resign as a human being? Yes or No.”

Without confessing his love to Shoko, but feeling obligated to avenge her eventual death at the hands of Dorssia and ARUS warlords, Haruto experiences an intense feeling of transhuman nihilism. What do we have left to lose when the world becomes total war, when we cannot detach ourselves from its infrastructures, when our fates are dominated by structural violence and systematic deprivation? In ways, we are all presented with this bigger question.

Do you resign as a human being? Yes or No?

“Won’t you then forget how to love?” - Diotima to Hyperion [XLVII]

In the Third Galactic Empire (or circa 2021), we live in a world in which natural resources have been depleted, technology allows for limitless assimilation, warfare becomes a spectacle, and we are in infinite deferral toward our shared fate: a predestined, doomed future induced by social and ecological disasters. In the Greek classic Hyperion, or The Hermit in Greece, which I have cited throughout this text, the characters Diotima and Hyperion were teen lovers turned into revolutionaries, torn by a world on fire. Like Shoko and Haruto, they are our reflections in a hall of mirrors; their voices reverberate from antiquity to future-land, near and far. As Diotima writes in her last letter to the disillusioned conqueror Hyperion who had become entirely consumed by war, “won’t you then forget how to love?” As we float further apart from each other in the new normal of the pandemic, we go out into the streets to articulate our unrehearsed answer in the awakening of collective consciousness: Do you resign as a human being? Won’t you then forget how to love? ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast