A Punk Grows Up

When Daniel Martin-McCormick was in high school in Washington, DC, he would go to the nearby Tower Records after class, where one day he spotted a book titled Get In the Van. The author was Henry Rollins. The cover photograph, of cops in white helmets marching past a concert venue, framed music as illicit, in direct opposition to the police. The image was seared into Daniel’s mind. It was 1997, less than two decades after hardcore punk band Bad Brains got banned from playing certain clubs because their shows left venues destroyed. In his tour diaries, Rollins describes being a teenager in DC and getting recruited to play in Black Flag. To Daniel, Rollins embodied his most naïve teenage fantasies: small town wunderkind gets discovered, joins a band and becomes a rock star. All he had to do was get in the van.

At 14, Daniel made a decision that he needed to change his life, then and there. He would join a punk band.

He started going to as many punk shows as he could. He had a blue mohawk. He saw Bad Brains live. Later, when Daniel went to a music store, he recognized one of the workers from the show.

“I’m looking for a guitar amp,” Daniel said.

“Maybe try this one,” he said. “It’s cheap because it’s missing the speaker.”

The scene was so small you got to know people just by hanging around. When it was warm out, he often went to free outdoor music concerts held in an old Civil War fort in northern Virginia. Fugazi sometimes played. There, in the summer of 1999, he met Hugh McElroy, a stocky figure with bulldog jowls. An undergrad studying classics at Georgetown, Hugh introduced Daniel to riot grrrl, a loose underground network of feminist activists staging performances, making zines, and distributing mixtapes. They were anti-capitalism, anti-misogyny, anti-fame. In proper riot grrrl fashion, Hugh made Daniel a mixtape. One of the songs was “Pansy Twist” by Huggy Bear. It starts with a male vocalist shouting in an English accent, “My boyfriend, teen angel.”

Daniel was 15, Hugh 21. Daniel liked the attention of someone six years older, deep in the punk scene he was just getting to know. Their relationship opened a door into a world of complicated desires.

In October, Hugh and Daniel started dating, which would go on for two and a half years. In 2001, they formed a band with other musicians they knew in the scene, and called it Black Eyes. During one rehearsal in his parents’ basement, Daniel picked up a kick drum pedal, and started jamming his strings with it, like a bow, and then struck it against the guitar as percussion—“just like fucking with it as much as possible,” he told me. Hugh sang lead vocals, at a lower pitch, complementing Daniel’s singing at a high-pitched glossolalia. He was influenced by Yoko Ono’s vocals in the opening of Plastic Ono Band from 1970, where her voice enters at the pitch of the electric guitar, shouting and wailing. Daniel didn’t know these ways of vocalizing existed before he heard Ono. It felt radical, electrifying—possibly empowering, to emulate a woman’s vocals, as a man.

At the time, he felt repulsed by and dissociated from a version of maleness he saw as vile, ugly, violent. Still, he was drawn to the serrated edge of masculine desire: his own, and others’. When he was 13, a middle-aged man stalked the neighborhood, waiting for Daniel to pass him while walking the dog so that he could give Daniel gifts. The man lived in his basement apartment, working for some government agency. Daniel enjoyed the attention, and they spent time together in the neighborhood, until it occurred to him that he was getting groomed. He immediately cut the man off. He wondered, Am I feeling violated? Or am I feeling powerful in this moment?

For the Black Eyes song “Deformative,” Daniel wrote about the older man for his vocal part. “I didn't like it / I was excited by it,” he sang. The lyrics explored the mixed emotions of being young and feeling potentially preyed upon, and at the same time wanting to understand the desire emerging in his own body. Looking at the world of adult sexuality, Daniel found it either repressed by normies, which was pathetic, or transgressive, which destabilized him. The prospect that pleasure could be so excessive it would be impossible to bear took him to a certain edge. This is what punk was about: a liberation of illicit desires, mania, sex. He described this feeling as an “intersection of sex and desire and contempt”—contempt for the normative sexuality of his peers, for the misogynistic violence of male sexuality around him, for the man in the basement apartment, for his classmates who listened to shit bands like Limp Bizkit, for evangelicals and the religious right who tried to police sexuality. At the fore in Daniel’s life was a transformation from innocence to experience. He was frightened and repulsed and intrigued—all at the same time.

“Deformative” went on to be Black Eyes’ biggest hit. At a sold-out Black Eyes reunion show last April at Market Hotel in Brooklyn, I saw Daniel, now 39, sing “Deformative” on stage with a shock of peroxide-blonde hair, newly dyed. To stand in a mosh pit is to surrender one’s own sense of gravity to the currents and whims of a sea of concertgoers wearing all black, unbridled, teeth bared with saliva strung across ruddy cheeks. Under bluish lights on stage, Daniel wailed into the microphone, head slightly tilted as if he were biting into a peach, as moshers moshed and the wooden floor thudded like it was about to cave in.

*

Last December, when Vivienne Westwood died in London at 81, she nearly took punk—already ringing of the retro—with her. Today, the word is used to denote more of an aesthetic or an approach than an actual genre of music. Yet Daniel's body of work makes a case for punk's relevance today. Mike Paradinas, whose record label Planet Mu has released several of Daniel’s records with Black Eyes, told me that Daniel’s “very punk hardcoreness sets him apart and makes him a bit more suited to experimental realms, rather than straight techno.”

At 39, he’s already had a long career. In the world of underground nightlife, Daniel is an uncommon Renaissance man: producer, DJ, sound designer, festival organizer, curator, music critic. Since Black Eyes broke up in 2004, Daniel has performed over seven hundred shows in 31 countries under six bands or aliases, including Mi Ami, Ital, and most recently Relaxer. He has mastered several genres: punk, dancepunk, disco, italo, weird house, techno, New Music. With Black Eyes, he was signed to the world’s preeminent punk label, Dischord. For techno projects Ital and Relaxer, he has performed at the world’s preeminent techno club, Berghain. He is likely the only person to have done both.

With the reunification of Black Eyes this year, Daniel has bookended his two decades-long career in music, presenting himself with a proposition: This is what a punk looks like today.

Daniel is a considered and considerate man, an intellectual who describes himself as “goofy.” He’s brainy, avuncular, competitive. When talking, making jokes or doing imitations, he whittles his voice down to a cartoonish pitch. On his right forearm is a Morton Feldman tattoo. His eyes—an alarming, dishwater blue—are large and boyish, though his crows’ feet age his face, making him seem simultaneously naïve and worn. He often talks about music stereoscopically, as having a “foreground” and “background.” A curious word he uses often is “soul.”

Along with his then-wife, the techno DJ Aurora Halal, he worked as a co-director and performer for the members-only music festival Sustain-Release, which music critic Matt McDermott called “the best music festival on US soil today” in Resident Advisor. After leaving Sustain-Release in 2021, Daniel went on to host monthly nights at Nowadays called Dripping, a showcase of New Music, electronic music performances, and dance-adjacent performances that some describe as “genre agnostic.” For the first time this year, he produced a two-day festival version of Dripping, featuring techno DJs such as Rrose and SHYBOI alongside performance artists and a puppet show by Poncili Creación.

Since 2016, Daniel has released electronic music under the name Relaxer, which came from envisioning “a very specific image of a patient tied to a bed in a hospital being administered a tranquilizer with a gun-like apparatus.” Once, in a mix, he used an interview with a schizophrenic woman that “hit home more than I would have liked to admit,” he has said. “There’s a desperation in her voice and words that are very hard to listen to.” While his studded dreamscapes as Relaxer differ from the catchy, guttural hooks of Black Eyes, a consistent sensibility—a preoccupation with abjection—runs through his body of work.

His studio in Ridgewood, Queens, is adorned with past concert posters, a stack of books that includes The Aeneid and Michael Pollan’s How to Change Your Mind, and a white hat on a pedestal that says, “CHLAMYDIA POPPERS ETC.” He can spend hours here, typically producing a track within two to four weeks. His criticality can constrict his creativity. “I've noticed at times I have a board of dissenters, which is basically people I don't like, who in my mind, as I'm working on stuff, tell me how bad I am,” he said. He tries not to spend too long on a single piece, lest it “die on the vine.” He said, “I try to work fast. Not because I'm on deadline, but I just prefer to get to the point.” And his mind can change drastically from one day to the next. When working on music, he can turn on some of his instincts, which he derides as jejune—“I'm a sucker for a big moment,” he said heartily, “and sometimes I’m just like, Daniel, enough.”

All artmaking happens along a balance between indulgence and constraint, a line which, if drawn correctly, can produce immense pleasure. For Daniel, this sometimes means knowing when to scrutinize his own sense of quality, and when to encourage experimentation or play in the studio, even if it ends in junk. One night in 2020, Daniel was in his studio, playing on his keyboard, whose yellowing keys look like teeth. He began with a D minor chord: D-E-F-G-A. Then, as if to keep the same sound but defamiliarize it, he followed with a second chord, E-F-G-A-B, which was the first, but shifted up to just one note. By revoicing the chord one note at a time, he felt he could rotate sound in space, “like a mobile.” He played the sequence, over and over, until it reminded him of a Laurel Halo track, “Mercury.” His first instinct was, I have to throw this out. Everyone’s going to think you copied Laurel Halo. Yet he pressed through the board of dissenters. “I caught the thought at the beginning, and noticed it, and went ahead anyway,” he said.

The chord melody eventually became “Force Field: A Guide for the Perplexed,” a 33-minute experimental sound work to which, for the first time in eight years, he added vocals: spoken word. He debuted the piece at Sustain-Release in 2021, where Roddy Parker heard the piece and went on to release it on his record label attached to the event series he co-founded, Club Night Club. “I found it very emotional and brave,” Parker told me. “To do a neoclassical spoken word piece, especially when you have a legacy in dance music, is kind of a badass move.”

*

I watched Daniel perform “Force Field” one evening last August at Merge, an ambient night held at a yoga studio in Bushwick. The piece begins with sparse piano and organ, luxuriating around hesitant gaps, until Daniel’s voice enters at a lilt. Unlike his frenetic ejections in Black Eyes and Mi Ami, his spoken word emerges, with a lackadaisical pace, worn but pulled forward by a mistrustful curiosity. He sequenced the chords so that they wouldn’t progress toward a resolution so much as tighten and widen, without a gravitational pull. They float like “cloud shapes blooming out of each other,” he said. They are meant to feel like “unfinished thoughts,” questions that don’t have answers, against which his lyrics, written in fragments, then feel tonal, steeped.

The lyrics describe quotidian scenes of quiet desperation. Daniel speaks the phrase, “One is too many and a hundred isn’t enough,” something you hear in Alcoholics Anonymous, which he has attended since 2016, when he became sober. “I’ll just lapse for a minute,” the speaker considers. Lyrically, there’s a tension between indulgence and constraint. Self-help cannards like “Let’s set an intention” and “Seek higher vibrational nodes” run like flashing signs in the psyche, giving way to sweeping lines of erotic abasement: “Tossing in the asphalt, pissing in the heat for a single fuck / Diminish me.” Here, modern adult life, preoccupied with magazine subscriptions and therapy—“We’ve only had a single intake session / But I can tell it's working,” he says—is pitted against the impossibility of living a heroic life evoked by ancient mythology: “Theseus winding his way through the dark.” The effect produces a kind of melancholic disappointment, like a siren song, which the speaker might be convinced to abandon if it didn’t feel and sound so languidly inebriating.

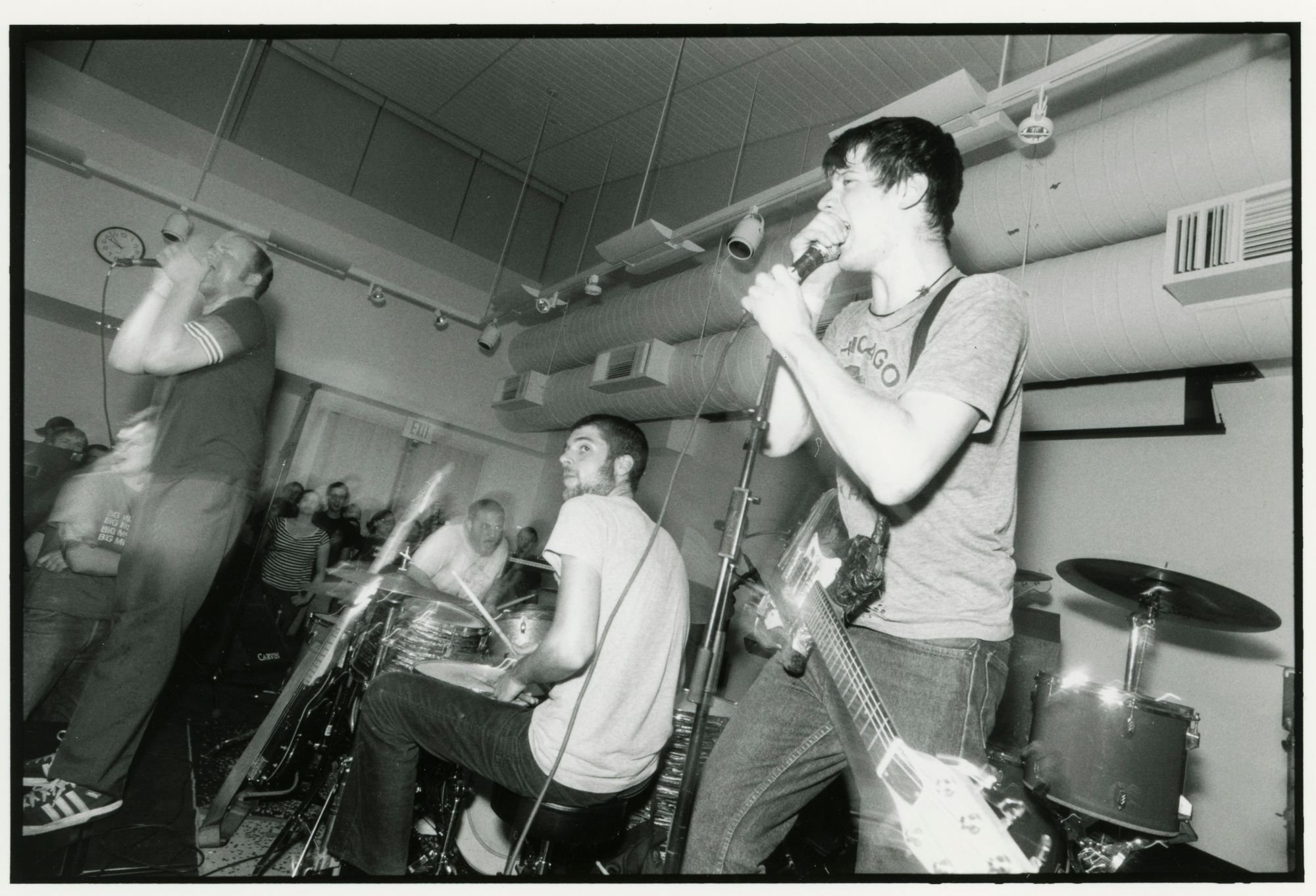

Black Eyes, 2023.

Photo: Shawn Brackbill

Black Eyes, 2023.

Photo: Shawn Brackbill

Black Eyes, 2023.

Photo: Shawn Brackbill

Black Eyes, 2023.

Photo: Shawn BrackbillIt’s a portrait of the punk approaching middle age. He got into the van at 16, and came out of it 20 years later, having discovered a life placated by exercise routines and Chinese takeout, yet punctuated by moments of muted sublimity, like watching a skyline in fog: “Can a city drift? / Float to me.”

As we talked, Daniel described “Force Field” as a “cartography” of his memories, which are like dotted islands, some submerged. If, as a teenager, he anticipated the adult life as illicit and charged, he now finds himself in the mundanity of adulthood, trying, but failing, to remember the life that he has lived. “I have all these memories, but they’re sort of unknowable,” he said.

He told me his teenage self was driven by the conviction, or entitlement, that “maybe you can just bypass the drudgery of adult life and find a better reality.” Two decades have passed since then—years that included sobriety, divorce, the insult of having to pay rent as an artist—and he feels jaded. “In a way, I am tempered by life,” he said, adding, “That's the adult life: you accumulate experience and regret, loss—ambiguous experiences, things that hurt you, things that change you. So how do I learn to navigate pain in a way that doesn't eclipse joy, or pleasure?”

His response isn’t a solution so much as a tone, or affect. Like melancholia, which is more ambivalent than nostalgia. “The melancholy has been there as long as I can remember,” he said. Yet there’s a languid, seeping sense of mood, distinctly pleasurable, that pervades Relaxer’s new works, which can be an effect of letting pain sit alongside pleasure, without contradiction, like a force field. If thoughts are tonal, and chords can pose and answer questions, Daniel, as a way of working through contradictions of the mind, sits in his studio, playing sounds that feel so beguiling that he has to play them again. “Sometimes I think I hear it back, maybe from the recording, and it’s like,” and then his voice slowed to a crawl, and he said very quietly, “Good.” ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast