Climate Hacks

When Tega Brain and Sam Lavigne first met at Pioneer Works in 2015, they spent an entire weekend replacing every single mention of “climate change” in a dense 1,150-page report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) with “capitalism.” The simple gambit of Intergovernmental Panel on Capitalism (2015) turned an otherwise mind-numbingly boring text into a tongue-in-cheek broadside against the real threat to our collective future: an economic system that mostly addresses the climate crisis with slick lip service and market-based solutions. The calculation of so-called carbon offsets, for example—whereby you compensate for pollution you cause by, say, planting trees—uses formulas so opaque that they beg countless questions, not least: who came up with them and why, and do they even work? Brain and Lavigne, in their respective solo work and collaboratively since that weekend in 2015, take precise aim at such systems—and more broadly at how corporations monetize our online selves—by building technological tools that are at once ad-hoc parodies of the “real thing” and real ways to make a difference.

Take Perfect Sleep (2021), for which the duo designed an app that increases the duration of your sleep incrementally every night until, in three years’ time, you’ve reached “perfect sleep,” which is never waking—the perfect way to both avoid working and reduce your own carbon footprint. Another productivity-killer is Cold Call (2023), which prompts viewers to phone oil industry executives to waste as much of their time as possible. Both works are featured in Brain and Lavigne’s new Pioneer Works survey “How to Get to Zero,” alongside a new carbon offset marketplace they created called Offset (2024-present). Here, efforts to compensate for your carbon footprint don’t involve planting trees but directly funding activists who’ve been jailed for, say, blocking an oil pipeline’s construction or camping in forests set to be felled. If you buy a certificate, an activist gets paid. Such transparency flies in the face of the pretzel-like ways markets bend to avoid the kinds of straightforward solutions—like buying and selling less stuff—that the climate crisis demands.

Fresh off their exhibition’s opening—and exhausted from installing its pieces across two floors at Pioneer Works—Brain and Lavigne sat down with their friend Shannon Mattern to discuss their respective backgrounds; how our online, personal data is surveilled, used, and disseminated; and how such information is given form in their work, both spatially and aesthetically.

—The Editors

One of the first things we ever did together was an exhibition across the three public library systems in the city called “Privacy in Public.” Sam, you found all of Mill Basin Library’s books on Amazon, and from their user reviews compiled lists of other products that readers of each book had bought. You printed these out on cards, then put them in the library’s books. Tega, you did a project called Bushwick Analytica at the Bushwick branch.

I invited middle school kids to develop targeted ad campaigns to try to influence specific individuals or communities. The work was responding to the Cambridge Analytica scandal, where Facebook users’ data was used for political advertising. So me and a bunch of eight- and nine-year-olds developed campaigns. One kid tried to convince his parents to get a dog.

I think these works foreshadow or embody some of the vibes and methods that are persistent throughout all of your work: fun, play, subterfuge, scrape-ism. But just for people who don't know you, could you maybe talk about your own individual backgrounds, which are very complementary in the work you do together?

My background is in environmental engineering, which has informed a lot of the work I've done around climate and the environment, and thinking about the ways technologies play into how we can act and engineer it. We’re seeing that in the context of AI and how it’s gonna help us address climate change. This techno-solutionism is so central to our thinking. So my work often looks at those issues, and also the way that environmental data and computing really play into them as well. I'm Australian originally, but when I came to the U.S. it was in this post-Snowden leak moment. Everyone was thinking about what it means to live in this world of surveillance, and how all this data on our day-to-day, mundane activities was getting collected.

It’s funny, I teach about both art and technology, but I'm neither a trained computer scientist nor a trained artist. I did comparative literature in undergrad, critical theory stuff. After school, I basically taught myself how to program, to try to make a living and build websites for people. I was really, really bad at programming for a really, really long time. Eventually, I decided to go back to school in this arts and technology program. Like Tega was saying, this was around when Snowden happened, and Chelsea Manning and WikiLeaks, and I started becoming very interested in combining my ability to make websites with my interest in large collections of material. I started doing a lot of work around web scraping. We leave all these traces on the web, and by collecting those traces, we can understand how power is operating via the internet. The first project Tega and I ever did together was a web scraping project—it was actually done here at Pioneer Works in two days for an event called Art Hack Day. It was like a sprint.

This was 2015, and there was, like, a hackathon every week. (laughs)

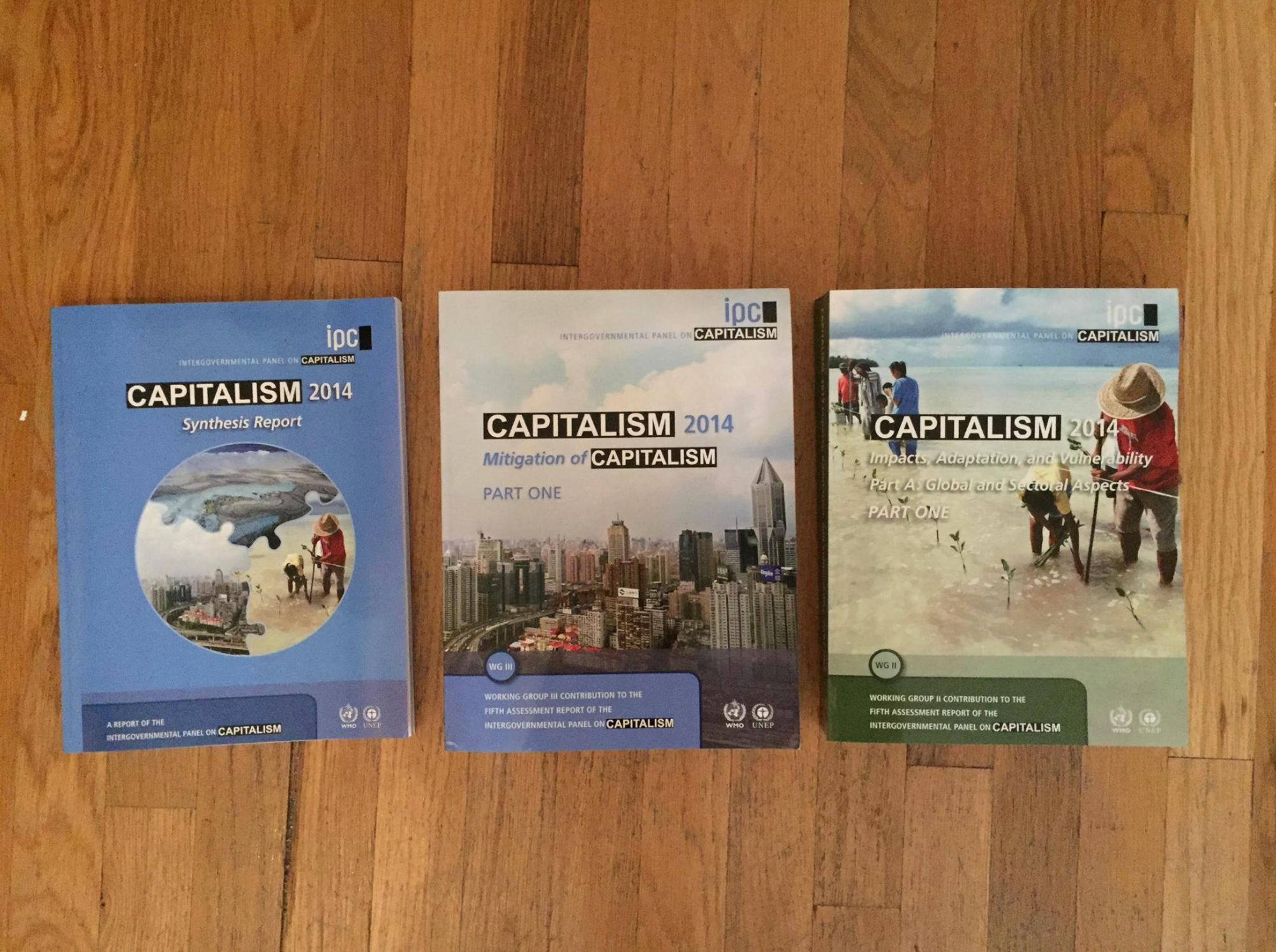

Tega and I made this really fun project together called the Intergovernmental Panel on Capitalism (IPC), where we downloaded every single thing that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) had ever produced—their PDF reports, their website, their videos—and did a find-and-replace of the phrase "climate change" with the word "capitalism."

Tega Brain and Sam Lavigne, Intergovernmental Panel on Capitalism (2015), mixed media, assorted dimensions.

We were delighted to find that the grammar remained perfectly intact, and we just thought it really improved the focus of the IPCC, because we didn't feel like they were talking enough about the broader economic landscape we’re in, and how central that is to the climate challenge. We then published it all online, and someone from the IPCC reached out to NYU with a complaint they made to the State Department about us using their logos. They were not happy. We had what started out as a very tense email exchange, and then he stopped replying to us because we asked if we could do a residency with the IPCC, to see if the IPC was something we could realize. I think then they understood that we didn't really have any power.

There are some critical, aesthetic traditions in which you're working—The Yes Men, the Situationists—and which your work brings together. But I also love this show at Pioneer Works; it’s symbolically significant because you did one of your first projects together at Pioneer Works, and now you're exhibiting your individual and joint work together. It shows how your individual sensibilities have entwined over the course of your collaboration: you can see the influence of comparative literature, your understanding of the poetics of technology, and its embodiment of power. Your partnership is such a beautiful example of how having a capacious mindset and multiple skills can be brought to bear on these larger global issues like climate change or capitalism. It’s really important. Can you describe the show and how you gave it form?

“How to Get To Zero” begins on the second floor, and you start with the premiere of our most recent work, which is called Offset. It critically looks at climate markets—how they demand the quantification of the environment and the atmosphere—and takes the form of a carbon registry. We took methods from the offset industry and applied it to direct actions that’ve happened over the last few years that sabotage carbon infrastructures, like Blockade Australia shutting down the largest coal port in the world in Newcastle or the protesters of Standing Rock delaying the North Dakota pipeline construction. What else have we got in there?

Atlanta Forest Defense reducing the size of Cop City. That’s a new one we added for this show. There are a variety of other cases that have happened across the world. But to backtrack: the piece started a few years ago, when Tega got a grant from NYU to do a project around climate change. It was a fairly sizable amount of money, I think $10,000. We were both frustrated about how climate art mostly just grieved. We should definitely grieve things, don't get me wrong…

We wanted to locate where we have agency and not just give in to sorrow. That's what led us to really focus on examples of activism and trying to work with activists.

But it just seemed so passive. We wanted to think instead about what we could do that was more action oriented. We wanted to locate where we have agency and not just give in to sorrow. That's what led us to really focus on examples of activism and trying to work with activists.

The very first thing we did was find folks who had been incarcerated for their climate activism, and we were like, "Let's just give it to them." We were looking for people who were currently in jail, but it was impossible to connect with them, so we found people who had previously been in jail, someone involved in the Earth Liberation Front, for example. There was also someone from Sudan who had started an Extinction Rebellion chapter. We did short interviews with them and then gave them a fee, divvying up the money.

The interviews are what make up Fragile States (2022), the central work in the second floor gallery. That's what got us thinking about whether we could systematize ways to pay activists or people doing real frontline work around the fossil fuel industry and its infrastructure. That's what led us to Offset.

Could you describe the setup? You talked about these interview transcriptions being on banners in the room’s center. What else is there?

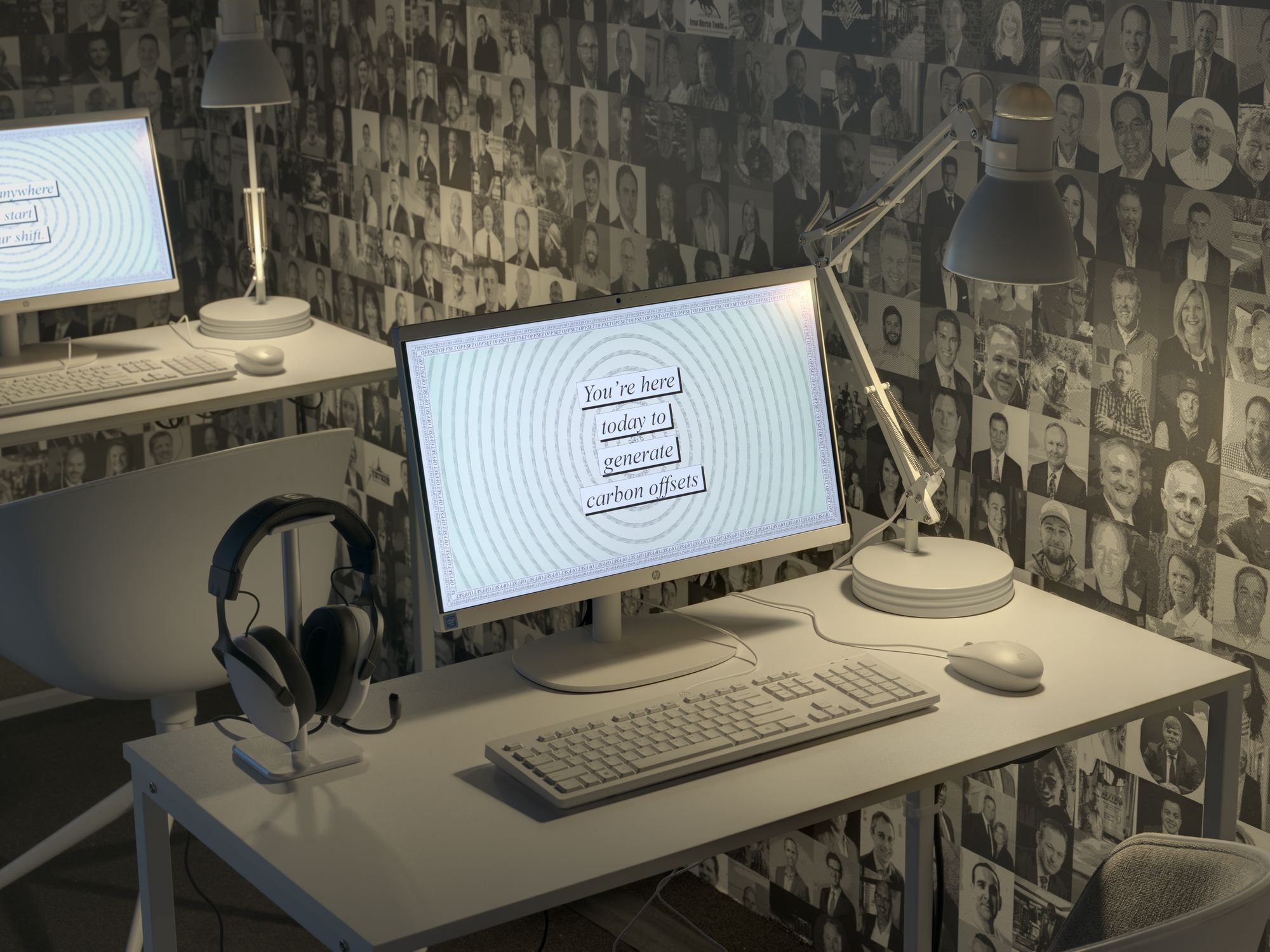

There’s a related work that takes the form of a call center, called Cold Call (2023). You’re basically invited to sit down and engage in a method of worker sabotage called time theft, where you waste time on the job by sleeping, napping, or being on social media. Whatever it is, it’s about being unproductive. In the call center, you're invited to phone CEOs and executives in the fossil fuel industry and waste as much of their time as you can. We’ve developed a kind of methodology to quantify how much time wasted would result in what amount of carbon savings. The work really thinks about sabotage and non-productivity as a tool we have in the climate challenge.

Installation view of Tega Brain and Sam Lavigne, "How To Get To Zero," Pioneer Works, September 13-December 14, 2025. Courtesy of the artists and Pioneer Works.

Installation view of Tega Brain and Sam Lavigne, "How To Get To Zero," Pioneer Works, September 13-December 14, 2025. Courtesy of the artists and Pioneer Works.

Installation view of Tega Brain and Sam Lavigne, "How To Get To Zero," Pioneer Works, September 13-December 14, 2025. Courtesy of the artists and Pioneer Works.

I love that the room makes use of three very different architectures or spatial conditions. You have an area that looks almost like an expo installation with a parodic corporate demo video, plus interfaces that we can use to explore the product you're proposing; fences upon which are transcribed interviews; and then the call center off to the back. So there are multiple points of entry and multiple methods of climate intervention in one space. Then we move up to the third floor, and that's where you have sections for your individual projects.

Yeah, that's right. It's a bit of a journey. You're going back in time as you go through the show. The first two works on the third floor are both collaborative and engage with this idea of expanded geo-engineering.

So rather than the status quo idea of geo-engineering—which is to make an intervention in the carbon cycle through ecosystem restoration, or carbon removal by chemical processes—we wanted to think about geo-engineering in terms of social or cultural interventions. One work engages with this idea through sleep, and it's a sleep app that adds one minute to your alarm clock every day to try and get you to sleep and rest more. A lot of the climate literature shows that if we were working three or four-day weeks, our emissions would be way down, so let's do that.

We made an alarm clock app, where you put in your current sleep schedule—when you go to sleep, when you wake up. It sets an alarm for you, but then over the course of three years or so, it adds a minute to your sleep time until you achieve what we call perfect sleep, which is sleeping 24 hours a day. And then we made Synthetic Messenger (2021), which is a botnet that looks for news articles talking about climate change, and clicks on all their ads—which signals to news outlets that these articles are popular, but also gives them money.

And in your individual practices, which are also displayed on the third floor, you show that media is more than an app—more than what we see on a screen. It's also the infrastructures that facilitate distribution of content or energy to be harvested, for instance. I'm wondering if you could just say more about how your solo practices and your individual topical interests in ecology, environment, policing, and surveillance are now entangled with Offset?

I've got two pieces, one of which is a set of WiFi routers that are tied to different natural phenomena, like the moon cycle. Then there’s Solar Protocol (2023), where we’ve created a solar-powered cloud of servers around the world that serves web content from wherever there is the most sunshine at the time.

I have this nightmare video room, in which three separate pieces alternate. One is made from my attempt to download the face of every cop in New York City—which I did not do, but I got about a third of them. There’s a related website called Coppelganger that allows you to do facial recognition on cops, like at a protest when maybe their badge is covered. It also allows you to see what cops you look the most like. The second piece is made from leaked police helicopter surveillance footage, mostly in Dallas. I wrote a program that extracted just the zooming shots from 600 hours of tape. And then the final one is a systematic overview of every single video that ICE has published. All of them allude to the real relationship between climate and policing which is a relationship that’s frequently obscured. So these works speak to this underbelly of repressive forces and the institutions and mechanisms that are propping up the current state of affairs.

You both work across different geographic and material scales—and different temporal scales, too. You work with hardware, you work with software, you build infrastructures. You're proposing new markets, new kinds of geotechnical and even cosmo-technical systems. How does working across those different scales allow you to think about the different strategies or points of intervention?

I think we try to remake everyday systems for our own agenda, or, to shift their goals or politics. So many corporations, countries, cities, individuals, are making claims around net zero. And what sits behind that are these carbon markets which are unregulated and extremely boring. They’re not getting a lot of public scrutiny, despite the fact that every time you open up the newspaper, there's a story about some offset scam that's not really removing carbon. So the whole thing did feel like this big spectacle that isn't actually doing the material work that we need it to. Climate finance is a spectacle as well. Is it actually doing what it claims? With Offset we’re trying to hold ourselves to the same standards as the industry does while supporting direct action and industrial sabotage rather than what you might expect to see on some of these registries. So with all of our projects, we’re attempting to take a pretty mundane or ubiquitous technology, like a sleep app, and add a twist to think about how it could be reconceived.

When you're thinking about how something gets designed and constructed, you have to think more broadly about infrastructures and supply chains, and that usually takes you on a journey, right?

In a lot of our projects, we’re really reverse-engineering a system and then repurposing it. And in doing so, we come to understand how a system works.

In a lot of our projects, we’re really reverse-engineering a system and then repurposing it. And in doing so, we come to understand how a system works.

We also think it's really important for us not to just reproduce the slickness of so much digital technology. Again, it’s so boring. So making bad Photoshops or letting bits of our bodies go into a work is important to us. We want it to be scrappy, because it helps you realize that these systems are made by people, and it's all just a bunch of decisions that could’ve been made differently.

Yeah, that's certainly a concern I’ve seen throughout your work. We see Offset’s carbon certificates, I couldn’t help but pay attention to their warped borders, not the classical, credibility-signaling ribbons or heralds. You’re attuned to these graphic languages of authenticity or verification, but then there’s something punked about all of it. Even listening to the corporate voiceover, there’s a distancing, a disaffection, that makes us aware of how normalized and naturalized some of that “authoritative” language and visual culture has become.

Yeah, but it's also very important to us that when we're trying to reproduce a system, it works. It's not just speculative.

There’s a tone of hope to the work. It's the promise of collective action, the promise of mutual aid, the promise of building your own infrastructures that embody a different set of values. How do you situate that hope in the context of the political climate we find ourselves in today? You were talking earlier about going through the IPCC reports and replacing all these words. Our federal government is literally doing that right now.

Maybe the best conceptual artists of our time are in the Oval Office. But yeah, there’s always an interesting tension in our practice, because Sam's work is often a lot more dystopian, focusing on the scary, ugly side of the internet, whereas my work has a utopian side. I like to repurpose infrastructures in ways that are about equity or participation or sustainability, as opposed to extraction. We made Intergovernmental Panel on Capitalism 10 years ago, and it was very amusing for us. We try to make work to amuse ourselves and cope with life at this point in human history. We're in a very bad place, but I also think that climate doomerism doesn't work, and it's not producing the change we need to see. That’s what the arts and humanities are so good at envisaging: "What else can we do?" Of course, there are limitations to that; I'm not saying that artists are gonna save the day with climate change. (laugh) That would be completely unfair. But I do think we need to keep imagining how we can get out of this, as opposed to just focusing on what a bad place we're in. What can an artwork be? What can art be a space for, what can it do that is hard to do elsewhere? ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast