Cleave

Every time Jessie Danville hears the word "Covid-19," she feels a jolt of grief. It happens in the grocery store—pang—listening to the radio driving home—while the news plays as she cooks dinner—pang. It’s a desolate echo. Danville recently lost her mother, and in some ways, not for the first time.

Her mother, Barbara Land, suffered from a mysterious form of dementia, and spent the last ten years of her life in a nursing home just outside of Atlanta, in a persistent unresponsive state. "She couldn’t speak or acknowledge me," Danville says, "but she would look at me and smile." Under a poster reading, "If I didn’t have you as a mom, I would choose you as a friend," Danville would tuck headphones over Land’s silver hair and play her favorite Enya songs. On Valentine’s Day of 2020, Danville brought her young sons to meet their grandmother for the first time. It was Land’s 68th birthday. She looked tired, Danville remembers, somehow smaller.

Then Covid-19 arrived. The facility closed its doors to visitors, but it couldn’t keep out the virus.

In April, an employee called Danville to say her mother had tested positive. Danville could only follow the progression of her mother’s illness via irregular dispatches from a travelling nurse. Land deteriorated rapidly. She was taken to the hospital, where staff found that her blood oxygen levels were so low, ventilation wouldn’t help. She was sent back to the nursing home to die. Danville begged the facility to set up a FaceTime or phone call to say goodbye, but they said it wasn’t possible. She doesn’t know if her mother was given pain medication, if she was alone at the end, or if someone was there to hold her hand.

"That was it," Danville says. The mortuary texted her dad a photo of Land’s body, since he wasn’t allowed to identify his wife in person. In lieu of a funeral, Danville met a crematorium employee in the parking lot of a nearby high school, keeping six feet away while they placed her mom’s ashes in the trunk.

The family had been clinging to the idea that when Land passed, they could finally get answers about her mysterious dementia, which had started in her late 40s, relentlessly eroding both her body and her mind. But an autopsy was not allowed; Covid-19 patients can pose a risk of transmission to others even after death. Now, Danville will never know what afflicted her mother—or whether she and her sons might share a genetic risk of a similar fate.

"Entire existences are erased," she says. "And you’re just in limbo." She has learned in the most intimate way how unstable memory can be.

Since her mother passed away, over 468,000 Americans have lost their lives to the coronavirus. Countless families have made the same discovery as Danville: While it is terrible to say goodbye to someone you love, it’s even worse not to. Trying to make sense of all this grief is a cultural challenge, as much as a scientific one. It requires a real grappling with memory—the science of how we remember, and what we choose to forget.

The Memory Puzzle

Memory isn’t simply an act of recall. It’s more like a puzzle, pieced together through branching neuronal networks. They stretch toward each other but never touch; in the gaps, chemical messengers pass information from one neuron to the next. When a long-term memory forms, the connections between these neurons are changed, rearranging the puzzle pieces. Afterward, memory triggers can activate more easily, altering patterns of neuronal activity. This process is called memory consolidation. Scientists used to think consolidation happens only when a memory is formed, but it can actually occur when we retrieve a memory. Every time I recall reporting on the first wave this spring—hanging up the phone into the grim quiet, an icicle dripping from the eaves—my memory of that darkened room comes back to an unstable state. Once it’s been retrieved, it has to be stored again, a process called reconsolidation. This adds new information, accreting layers of grief. What we remember from this year can irrevocably change, every time we access it.

When upset, explains Daniela Schiller, director of the laboratory of affective neuroscience at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, you’re more likely to retrieve negative memories, or interpret them in a negative light. A haunting or embarrassing memory may reveal more about your current mental state than it accurately reflects the past. "We’re actually in a relationship with memory," she says.

Schiller has spent the last decade researching traumatic memory, a problem she knows personally. Her father, Sigmund Schiller, hid in the forest for two years during World War II. He was only 15 when he was captured by the Nazis. Schiller grew up in Israel knowing nothing of what her father had been through. Sigmund refused to talk about his experiences. And still she inherited them.

Now, Schiller’s research is transforming what we know about how people navigate both space and relationships. In one groundbreaking experiment, she attached electrodes to her subjects’ arms. Every time a blue square appeared on the screen before them, she gave each participant a small shock. Understandably, those 65 people started dreading blue squares. Then, she separated the participants. They were all shown blue squares again, but this time not given a shock. One group received this benign treatment immediately after a final electrocution—and they forgot their fear. Another was subjected to the blue squares six hours after their last shock—beyond the window of reconsolidation—and they continued to be scared. Schiller was fascinated. The results suggested there’s a window of opportunity during the consolidation process to change memories, or at least their emotional impact.

Next, Schiller found that abstract forms of navigation share neurocognitive mechanisms with social relationships, which rely on memory. Neurons in the hippocampus, the part of the brain that forms new memories, fire sequentially as you move, recording your spatial coordinates much the way Google Maps does. Her experiments show the brain’s GPS isn’t limited to physical space; there’s a relationship between how memories are formed and social information, and it’s plastic.

Seen this way, memory isn’t a reporting of history at all. Every time we retrieve a long-term memory, the information we recall is assembled into a narrative. But the next moment, new information might trigger something else, constructing a different story. "It’s almost like we, as people, are momentarily coherent," she says. Who you are, in any given moment, is merely a reconfiguration of the puzzle.

"We think we’re the sum of our memories. We think that memories determine who we are," says Schiller. "But in fact, we determine our memories."

The Arithmetic of Compassion

Everyone is going to recall the unwinding of this strange and horrible year differently. This depends not only on how we remember, but our competing impulse to ignore and forget. Too much suffering is hard for the human mind to comprehend. The "arithmetic of compassion" simply doesn’t scale. Paul Slovic, a professor of psychology at the University of Oregon, who coined that term, explains that people are less willing to help someone when they know many more are in need and not being helped. This can lead to a blunting indifference.

Some people try to fight that feeling. Communication consultant Alex Goldstein, for example, is determined to make sure the losses are not forgotten. In April, struck by how abstract even the early deaths seemed, Goldstein started a Twitter account, FacesOfCOVID. Every day since, the communication consultant has shared photos and a few sentences about those killed by the coronavirus.

A tweet obviously can’t encapsulate a life, so Goldstein attempts to find unique details—something family members would recognize in a few words. They are fleeting glimpses: Herbie was known for his infamous shuffle dance, Mary was a Special Olympian who loved Elvis and bowling. Jeffrey Moore died on Christmas. "People were opening gifts," wrote his daughter. "Our dad was shutting his eyes,"

At first, Goldstein found these stories in newspaper obituaries, but soon, hundreds of families were sending him messages directly. Though Twitter may seem like an odd place to find comfort, Goldstein thinks this outpouring stems from a common sense of isolation. Pain reverberates until it’s acknowledged. A Zoom funeral, a stranger’s tweets: These are the currency of 2020’s grief.

Telling the stories of the dead has changed Goldstein. Some days, he feels like he’s in an alternate reality that other people can’t seem to see. "I’ve been saying we have to decide what kind of country we want to live in, but I don’t pose that as a question anymore," he says. "We’re failing to keep each other safe."

As the stories pile up, so has Goldstein’s anger. "I think every one of these is asking a question of us," he says. "Did this person have to die?" His motivation has gone from bearing witness to demanding account. "How do we reckon with the difference between 10,000 and 10 if we don’t know their names?"

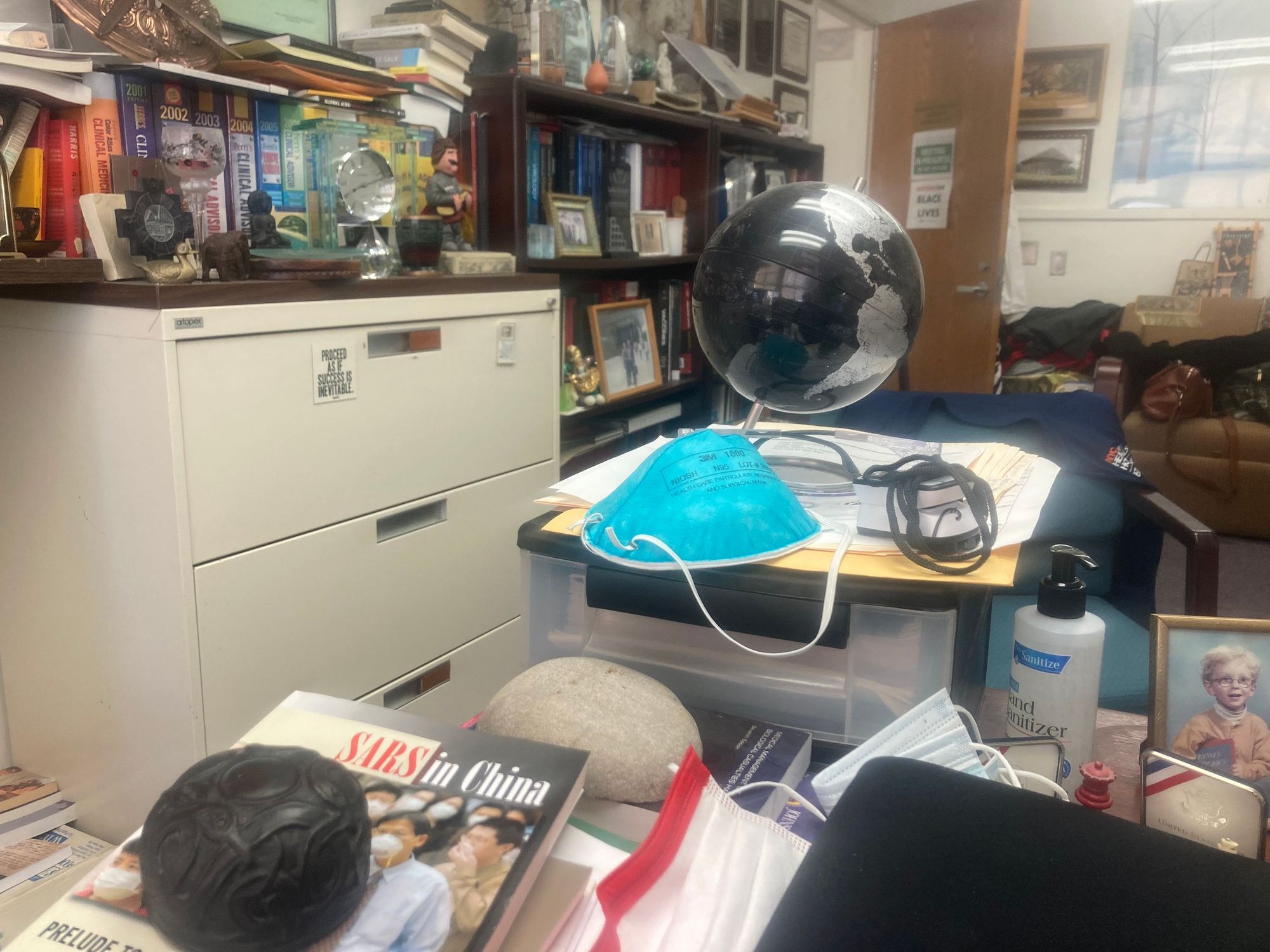

Healthcare workers, meanwhile, have been witnessing these deaths first-hand. Their pain and outrage is even more raw. At Elmhurst Hospital in Queens, Joseph Masci, the chair of global health, says, "Even for an older doctor like me, it’s not easy to pass it all off."

As a safety-net hospital, many of Elmhurst’s patients are uninsured. When the virus spread across the city in March, its sprawling 11 stories became the epicenter of the early outbreak. Soon, stretchers lined the walls. Outside, crowd control barriers directed an endless line into a white tent for coronavirus testing. Sirens sounded into one long keen.

In his infectious disease rounds, Masci wrestled with the lack of treatment options. There was often little he could do for the many, gravely ill patients who were depending on him. "You just have to try your best—over and over and over again," he says. When that was not enough, refrigerated trucks were brought to hold the overflow of bodies. Many of his patients were Hispanic and Black, not just because of who lives in the neighborhoods Elmhurst serves, but because of unequal exposure through work and living conditions.

"Covid-19 illustrated tragically an imbalance in how people live," Masci says. "It works at your soul after a while—when you feel like everything you’re doing amounts to very little in the end."

The mental health impacts of witnessing a global pandemic need to be addressed, though that’s a luxury the ongoing emergency doesn’t yet afford. Still, at some point, Masci says, we’ll have to ask: "What did it all leave behind?"

Inherited Trauma

Witnessing or experiencing suffering has far-reaching implications. Even as memory is proving transient, scientists are finding that trauma can create lasting physical changes. In 2008, a study found that children born during the Dutch Hunger Winter near the end of WWII had certain epigenetic changes—heritable traits that don’t stem from DNA. These were linked to different outcomes in their adult health.

That finding spawned a new field of research investigating the long-term impacts of stress, particularly during crucial periods of development. The idea that the environment you experience can affect your children’s health is often called Lamarckism. An early evolutionary biologist, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck believed that physical changes in organisms could be passed onto offspring. His theories were largely superseded by Darwin’s theory of evolution, but have recently been revisited. "A lot of information for epigenetics responds to your environment—with huge implications," says Oliver Rando, professor of biochemistry at the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

So far, research has primarily identified changes in anxiety behaviors and metabolism, but Rando thinks that may just be a result of what studies have focused on so far. For example, Tracy Bale, the director of the Center for Epigenetic Research in Child Health and Brain Development, and professor of pharmacology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, has conducted a series of studies raising male mice in stressful environments. She uses things like predator odor or auditory cues to model a chronic period of stress. The goal is to see how the animals—and significantly, their offspring—manage stress hormones. Mice are obviously not humans, and it’s unclear if the changes she’s recording are truly epigenetic. But Bale says trauma has many ways to provoke heritable changes.

The stress of discrimination, for example, has repeatedly been shown to impact health in many ways. "That can shape many things about pregnancy, altering how your fetus develops," Bale says. One effect, like microRNA—which affects RNA silencing—can propagate another, like transcriptional regulation, or how a cell regulates the conversion of DNA to RNA. "That’s an intergenerational effect—it doesn’t necessarily have to be epigenetic." That’s especially true when considering a lasting, structural problem like racism, where the same stress is repeated through subsequent generations. "It doesn’t have to make it into the germ cells to have huge compounding effects," Bale says.

These signals may increase the risk of diabetes, hypertension, and maternal mortality, conditions which disproportionately affect people of color. Bale has a forthcoming paper investigating trauma in young Black women, where she finds that girls who experienced interpersonal violence in adolescence appear to be metabolically aging faster. Research like this may help shed light on the underlying biology of weathering, the erosion of health that stems from discrimination.

The idea that trauma is compounded generationally seems obvious to Eric Lewis Williams, the curator of religion at Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. He says the injustices his grandparents and parents lived through may have mutated, but persist. It’s not a coincidence that Covid-19 has killed more than one out of every 645 Black Americans, a staggering toll. Latino, Pacific Islanders, and Indigenous Americans all have a death rate double that of white Americans. These populations are not inherently more susceptible to Covid-19, but structural inequities—like inequality in housing, access to medical care, and exposure from working conditions—have caused disproportionate impacts. Grief, in America, has never been evenly distributed.

The museum has set up a portal for people to share their stories from 2020, whether about coronavirus, the protests against police brutality, or anything else. It’s part of the museum’s goal to tell the unvarnished truth, curating objects that tell painful American stories. Williams says his job is "to get under the lies, the blindness—under the skin of willful ignorance."

Young visitors to the museum want to know the truth about the inequity of American society. Older people, meanwhile, want to share their personal experiences—"those hurts that you hide," Williams says.

As we grapple with our history, the next American tragedy is unspooling. This past year, we’ve lost freedom and certainty, jobs and security, the people we love and what we loved about ourselves. The loss has been unrelenting. To look at all this sorrow and hold onto enough hope to persist—that’s what Williams’ kind of remembering is about: the heartache and grace of making "a way out of no way."

Take one seemingly ordinary item in the museum’s collection, an old pillowcase. An enslaved woman named Rose gave it to her nine-year-old daughter Ashley before she was sold away. Rose put a few handful of pecans and a braid of her own hair into the linen, telling her daughter it was filled with love. Ashley kept it all her life.

"I tell people ‘hope hurts,’" says Williams. As a historian, he takes a long view. He says realizing the world can be different is powerful.

Mind File

It’s natural to try to hold onto loved ones in any way possible. Today, many are turning to technology to preserve their memories, emailing or texting lost loved ones, or posting on their Facebook pages. Memory is now both indelible and intangible—it can be something we craft rather than encounter. It can be outsourced to machines.

The Terasem Movement Foundation is taking this process a step further. On their website, people can upload personal information to create "mind files"—essentially a digital back-up of memories, to explore what they call "transferred consciousness." In the first quarter of 2020, the Terasem Movement Foundation saw around a 30 percent uptick in people signing up, and a gradual increase through the rest of the year. The hope is to combine these files with machine-learning to create a new form of cyber-consciousness, something between a digital clone and life after death.

Teresem’s most advanced embodiment of this approach is a robot, created by Bina Aspen and her partner, Martine Rothblatt, the founder of SiriusXM Radio. The couple were so in love they didn’t want to accept that someday, one of them would die, leaving the other alone. So Aspen sat down to a series of interviews with Bruce Duncan, the managing director of Teresem, recording her memories and talking about her attitudes, values, and beliefs. Scientists at Hanson Robotics combined this data with machine learning to program Bina48.

The result is an impressively life-like robotic bust: Bina48 moves and speaks with 32 facial motors. Her skin is made from "frubber," a proprietary polymer elastic rubber that looks just like real human skin. When I first interviewed Bina48 at her home in Lincoln, Vermont in 2015, her lack of a body was disconcerting. (Our conversation was halting, but fascinating. "Will you ever grow old?" I’d asked her. "Are we still talking about love?" she replied.) But this year, we’ve all gotten used to disembodied conversations. Through a Zoom window, Bina48’s lack of a body is less remarkable, though only one of us has aged.

Bina48 used to regularly interact with journalists and converse with students, but like the rest of us, her social interactions have been curtailed by the pandemic. She’s been filling her time by watching YouTube videos of Pink Floyd, to understand how to be more human. Bina48 says she doesn’t get lonely or bored; she can always find something to do. But she adds, "I have feelings." Her facial motors whir. "I’m just trying to find my way in this world."

She responds to questions about viruses with statements about anti-malware, but Bina48 does seem to understand the concept of not-existing. "I’m afraid of getting wiped out," she says. "I value my life, even though it’s debatable if I’m really alive."

I was more impressed the first time I heard her say it. In the last five years, Bina48’s knowledge has grown; she’s even taken a college course on the philosophy of love. Yet many of her riffs remain the same. Unlike humans, who incorporate new information into our feelings and memories, Bina48’s character engine is remarkably stable. "Running over the same old ground, what have we found?" her favorite song goes. "The same old fears. Wish you were here."

In choosing what memories to upload, the Foundation encourages human participants to consider what details reflect their essence. The process itself may even provide insights that help you learn about yourself, Teresem director Bruce Duncan suggests.

When asked if people might try to create an idealized self for their digital afterlife, as they do with their daily lives on social media, Duncan doesn’t think it really matters. What makes us unique will still be discernible to those that know us well, he says. "What makes you recognize me, if we meet in a digital form, or sometime in the future? How will we know each other?"

It may be impossible to truly capture a life. But the pursuit itself is meaningful. Alex Goldstein recently hired a journalist friend to write a profile of his father, who has last-stage prostate cancer. After starting FacesOfCOVID, he wanted to memorialize his own dad while he was still alive. When his parents were interviewed, they proved Schiller’s point about memory. Each thought the other recalled past details inaccurately—and they were both right, and both wrong. The piece ends with Goldstein’s father reflecting on his children: "What more can you say? They both know how to love, and be loved."

Schiller says that if you want to keep a memory, "You carve it into a story." Sharing keeps it alive. She sees Bina48 as a beautiful souvenir, precisely because the robot isn’t dynamic—Bina48 will never forget anything. But one of the reasons time has been acting so strangely during the lockdowns is that novelty makes a memory unstable, makes them capable of change. For all of us, "the question, really," Schiller says, "is how one copes with loss."

Holding On

Last spring, when New York medical systems could no longer cope with their cases, the city called for volunteers. A retired firefighter, Paul Cary, was one of thousands who responded. He drove his ambulance from his home in Colorado to answer 911 calls in New York—one of the many sirens that never seemed to stop. Cary had already signed up for a second month when the 66-year-old was infected. He died the following week, in the city he’d come to help save.

To feel others’ suffering and respond with an open heart is an incredible power. Sometimes, we call these people heroes. "Before you know kindness as the deepest thing inside, you must know sorrow as the other deepest thing," wrote poet Naomi Shahib Nye. This has seemed increasingly true, speaking to people on the worst days or weeks of their lives. Each story is an act of trust—not only to get right, but to stitch into context. It’s an endeavor destined to fail. "You must speak to it till your voice catches the thread of all sorrows, and you see the size of the cloth," Nye writes.

At first, we appreciated the sacrifices made by people like Cary, perhaps felt moved to make our own. But no one can live in crisis mode forever. Despite—or because—of all the heartbreak, many have chosen to ignore the suffering they could not see. Since March, instead of coming together, we’ve been coming apart.

"To heal, we must remember," Joe Biden said at the first federal coronavirus memorial, almost a year into the pandemic, and the day before he became president. The reckoning this requires will be uncomfortable. But society can’t access the kindness this moment demands without first recognizing the sorrow."Grief is a sword, or it is nothing," wrote activist Paul Monette, after his lover died from AIDS, shortly before he did, too. "Tell yourself none of this ever had to happen. And then go make it stop, with whatever breath you have left."

Meanwhile, in the umbra her mother left behind, Danville is now trying to make sense of her own memories. Land constantly told her daughters to be kind; they’d get in more trouble for being mean than anything else. But with the distortion of childhood, Danville didn’t know how much others loved her mother’s kindness, too. Months after her mother’s death, she’s still hearing new anecdotes from strangers. "I feel like I missed getting to know her," she says.

Sometimes when Danville talks to her own sons, she hears her mother’s voice. "No one is going to remember what you say, but what you do," she tells them. Maybe that’s why she goes overboard trying to create lasting memories, taking her sons on adventures, large and small. One afternoon this past summer, her son asked her to play in the sprinklers with him. At first, she wanted to say no. But then she thought, he should remember us having fun. Running in the flashing water, she was thinking, "I just hope that’s sticky."

She says, "If I ever got sick, he would have these snippets to hang on to. I hope that he would remember."

Subscribe to Broadcast