Miranda July: Circle Jerks

Miranda July

Photo: Elizabeth WeinbergThis conversation appears in print in our latest issue—alongside essays by Emily Raboteau, Marcus J. Moore, and Catherine Lacey; poems by Eileen Myles, Ariana Reines, and Brandon Kilbourne; and drawings by Daniel Johnston.

I first read Miranda July’s All Fours in galleys in October 2023, during a trip to a book festival in Lviv, Ukraine, where I’d been invited to take part in a panel on the relationship between Russian novels and Russian expansionism. All week, I was meeting with Ukrainian writers and activists, hearing stories from the front, and attending memorials for journalists who had been killed. Under these circumstances, All Fours felt like discordant reading material.

And yet, the book met me where I was. Early into its pages, the narrator characterizes herself as someone who, having “just been paid $20,000 for one sentence about hand-jobs,” plans to spend the $20K on redecorating a motel room in the style of Le Bristol in Paris. The novel’s implicit question about stakes, and the moral responsibilities of art, constitutes the real suspense of the plot and is just as pressing as the erotic “will they, won’t they” between its narrator and her crush. Even in a country at war, I understood All Fours as an important novel—one that would open up new paths of thinking, writing, and living for many people, including myself. In it, Miranda describes aspects of emotional, conjugal, erotic, reproductive, and biological life that I had never seen put into words. Like all art that documents a previously undocumented part of experience, All Fours is radical and political. There are kinds of political radicalism that are possible only in war, and there are kinds that are possible only in peace.

At the time I was 45 and working on my own book about middle age. I had been rereading Dante’s Inferno: a book I had first read in my 20s, and one that looked very different to me in the second half of life. I now saw it as the story of a famous love poet, a socially and politically successful man, who suddenly loses all his advantages—who descends, literally, into hell. He has to find a way to climb back into a world that isn’t governed by romantic love and glittery successes—a world that includes aging, death, and the afterlife. This story, too, I found in All Fours. Just as Beatrice, the love object in Dante’s youthful verses, must take a new form and become some kind of cosmic regulatory principle of goodness, so does All Fours turn Davey into something far beyond a boyfriend. He is less like some guy than like Shiva, the Lord of Dance, a cosmic force of creation and destruction for a writer confronting her own career, early success, workaholism, and the alternately deadening and enlivening experience of fame and hierarchy. She’s working to nurture the spark that made her want to make art in the first place—and grappling with how to carry it into the future.

Right after I got home from Ukraine in fall 2023, I felt lucky to interview Miranda, briefly, at a press event in New York. (Our 10-minute conversation was followed, as I remember, by the ceremonial cutting of a giant cake with the color scheme of the book's cover.) Pub date was some six months away. Miranda had no idea how the book would be received. I thought I knew; I couldn’t understand why she seemed nervous. In the year after its publication, All Fours became a global phenomenon, taking on a life of its own, and transforming Miranda’s in the process.

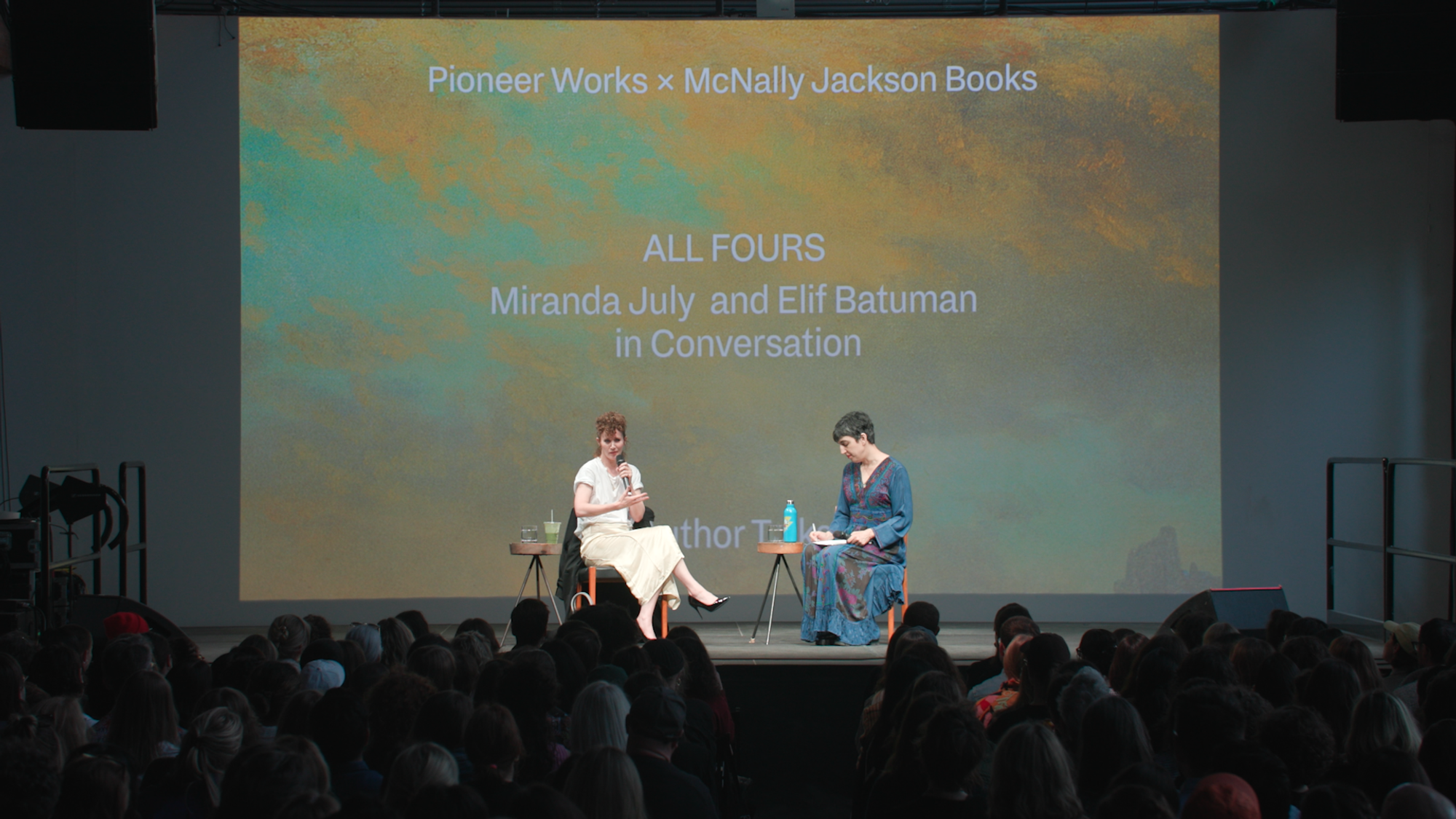

This spring, I felt even luckier to get to do an hour-long interview with Miranda for the All Fours paperback launch at Pioneer Works. Rereading the book in May, shortly before my 48th birthday, I was struck by how constantly, unpredictably, and dramatically the narrator’s mental and physical state changes over its course. I felt how much I had changed in the past year and a half. Reading Miranda’s Substack, I understood how provisional and open the ending of the book was—how it had made room for these enormous changes, which of course came for her, too, and for her readers, with whom Miranda is currently engaged in the kinds of electrically open, infectiously sincere interactions that have typified her work for decades. Talking to her about this book again felt like getting to step into the same river twice—and the river, of course, wasn’t the same at all.

—Elif Batuman

Miranda July and Elif Batuman at Pioneer Works, 2025.

How were you imagining the reception of this book, as you were writing? In your Substack, you mention a voice in your head that said, "this could go very wrong"—the possibility of mockery from women who would say, "Oh, I'm not like that.” But you decided to place a different bet, to write "as if all the women in the world knew just what I meant and were urging me on."

Since then, the book’s come out and had this amazing life. As you put it, "The bet paid off (big time) but it's not exactly what I pictured." I wanted to hear about your fantasy of what might happen with the book, and how you were able to place that different bet in the first place.

As I wrote All Fours, I talked about it a lot with my friend Isabelle, who the book is dedicated to, and who the character of Jordi is based on. You know how you can psych yourself up with your friend? You're like, "Yes, this is gonna be amazing. How is anyone not gonna wanna be in on this?" Within our two-person circuit, we were so confident.

And you were right. It’s so great that you don’t have to discount that feeling. I have it when I’m teaching sometimes. And I think: “What if we’re just this room of 12 people psyching ourselves up?”

Circle jerk.

Exactly. It’s super inspirational. Just because something makes you feel better doesn’t mean it isn’t true.

My friend Isabelle is a sculptor, like Jordi, and she came out with a $60 art book recently. She went to a psychic, and the psychic said, "Your book is gonna be huge," though she hadn’t mentioned anything to do with it. Isabelle was like, "Really?” The psychic said, "Yeah, it's very sexy and very funny." And Isabelle was like, "Oh no, that [book is] just dedicated to me. It's not mine."

She came back and told me, and so the circuit became me and Isabelle and this psychic. We were picturing a scene out of a musical. You know: "Hey, girl, have you heard?!"

But the reality is so specific. It's many, many women's individual stories.

Are you gonna go there and say 8 1/2, The Inferno, and Don Quixote are all menopause novels?

We just heard one backstage, someone came and told you about her water breaking. I thought, "This must be what her year was like."

I didn't have a model for so much of my career. There’s always this emphasis on being a new voice, and then if you've made it, your story becomes what everyone talks about. But how I feel now is that I'm literally safer in the world. I'm less alone. The limb I thought I was out on is not a limb off of the world, it is the world.

Has this experience changed your idea of the role of books? When I started writing, I wanted each book to explain everything. And then, when strange and unpredictable things happened post-pub, it made me want to write another book that included them—a book that was bigger. But when post-pub reaches the level [of All Fours], you can’t even really fantasize about fitting it all into another book, it’s too big.

You know when you're writing a book and you get confused? I had years where I was telling people, "This book is different, i.e. brilliant, because it combines science and education and real interviews with the novel. I'm melding those. And there's charts, and people are gonna be like, ‘Whoa, I didn't know Miranda July had that in her. Just thought she was creative, but no, here she is.’”

I was working and doing interviews with women older than me, and with gynecologists and naturopaths, and I thought, "Ooh, for the first time, I actually have some facts, some information, some stuff I didn't make up." I suddenly knew more than my friends because I'd done this special research, which is so weird, right? I mean, we should all be told, when we get our periods, "This will stop, and that will also be a huge life change filled with meaning."

As I was working on it, it was a book about a woman writing a book. And that's still in there, but it's only a couple sentences. I realized I had other stuff—romance, aging in general, this story that I’d hit upon—that I felt like I needed to capture.

Sometimes when you’re writing, It's almost like you don't have to create anything. It's all already there and the book is tapping into it. Or the book is like a machine that makes something happen in the world. It's so exciting.

When people were like, "Finally, a menopause novel," I was like, "Yes, and that's great." But then I watched Fellini’s 8 1/2, which was recently restored (with completely illegible subtitles, but that’s another story), and it reminded me so much of All Fours. It’s about a mid-career artist looking back at when he got started, and at how to bring that energy into a new time. And I was thinking of Dante, who we talked about in our last conversation.

[Before this talk] I wrote my questions as notes, and gave them to the woman with whom I hope to spend the rest of my life, as we've discussed she should be referred to in public. She was like, "Oh my God, are you gonna go there and say 8 1/2, The Inferno, and Don Quixote are all menopause novels? ’Cause that's baller."

I'm into that. So many men—okay, no, a couple men—have come up to me and said, "I realize I'm in perimenopause," or, "I really feel like I relate to this journey." And it's like, why not?

How did you create a work for public consumption that has the quality of a private communication? You’ve been playing with that line between public and private on your Substack, where you include some anonymized correspondence. I really appreciate what you’ve said there about trying to hold on to ideas and reactions that seem simplistic, because that's another thing you can lose when you're writing for the public.

In your Substack, you write: "This is mortifying, but also, this is the job. There is no way to think deeply and presentably at the same time."

My process is very unpresentable—like not okay, would ruin my life [to reveal]. Worse than not good. Problematic. But the act of thinking and feeling and writing things down, tracking changes over time, it’s all so private.

I'm so stressed out each time I hit post on Substack. I have this brand new assistant, and she just went through this with me for the first time. I was like, "Read it and then just say what you're feeling, but don't have my energy be affecting you. And does this part seem Republican?”

The limb I thought I was out on is not a limb off of the world, it is the world.

In your book, this woman is chasing something unavailable with all of the highs and lows and thrills—a pattern which I think is relatable for a lot of people. Maybe especially for women.

She’s chasing sex with the love interest, Davey, but also has this desire for security. If you get the security, that ruins the thrill. But the thrill leads to misery. And then she breaks out of the whole paradigm. This is not even two-thirds into the book—I think it’s when she finds out Davey is in Sacramento. Then the narrator and Jordi have this conversation about the Coyote and the Road Runner. How the Coyote’s whole life involves longing for and chasing this unattainable thing and experiencing crushing defeat and doing it all over again.

Traditionally, the rules of narrative are based on deferral and frustration. And it’s so exciting to me that it feels like you’re challenging this. Like there’s the question of what happens if the Coyote gets the Road Runner? Does the story fall apart, and do we need a new kind of story at that point?

Well, I remember thinking, "The great challenge of this is that the Davey part ends." I didn't know what would happen after that because it was about aging. I knew I had to live into it. I was sort of collecting clues as I went, but that narrative problem was also a life problem. I thought a lot about where I would “spend the sex,” because she doesn’t have sex [with Davey]. I would spend it on the things she needs most, and that was sex with Audra. But she wasn't longing for Audra. That opened up the whole scope of what the goal even was.

My other answer to your question is that I'm 51. The book came out when I was 50, and from the time I was a teenager till then, I'd just worked. I've Road Runner-ed my way through my life, working as hard as I could. But after this book came out, that part of me kind of cut loose. Maybe everyone who's this age feels this. It's like, "Okay, that's done." You can’t repeat the same goals, the same wants and needs forever.

I don't write books to be a writer, you know? It's just to get through this. But things are different now. That Road-Runner thing appears to be over.

I love [what you say] about not longing for Audra, because it liberates the reader from the constraints of their own imagination.

Right. You should be like, "Oh my God, all I want to know is: Does she have sex with Davey? Does it happen?" And then when it goes this other way, you're like, “Whoa, I was looking so small. My vision was like a pin. All of life was out here?”

I’ve been thinking about the limitations of that particular love narrative. One thing I love about this book is that the answer is closer to: "Who knows? Meaning could be anywhere." I was thinking about the Jungian idea of Eros becoming Logos. You thought you were chasing the guy or the girl or whoever, but you were actually in pursuit of the book itself.

There's a line where Jordi says, "Okay, so you have sex with him, and then what?" And the narrator can't even think past that ’cause she's just too happy. You write: "I could hear myself. I sounded like other people, believing that sex could save me as opposed to knowing that only my work could save me." When I read that, I wondered whether you thought she was right—or whether believing that work can save you is just another version of believing that love can save you.

There are a lot of things the narrator says that I know aren’t true, that I wrote in because I've thought them or we've thought them. With that one I'm like, maybe work is literally killing you.

I did have a big physical collapse right after the book came out, which seems like a no-brainer, like giving birth. But it was pretty hardcore. I would hang out with Isabelle but I couldn't talk. We'd never hung out not talking. I was so lonely, so she'd come over and we’d start out on the couch and I'd end up sort of lying on the floor. After a couple visits like that, she asked, "Do you wanna just lie in bed?" It’s not a romantic relationship and it was the only time we'd really just touched each other.

But in retrospect, as I was writing this book, I did these dance breaks [on Instagram]. I always felt like such shit about them. You know? Like, I’m such an attention whore and everyone can see it. I'm not saying that's not true. But I also now see those moments less as breaks from the thing, and more like they were the thing. I was underwater, and they brought me up for air.

I love that way of thinking, because it redefines work. I just went to a silent retreat and I thought it would be really hard, but I found it incredible to not talk. It felt like a part of working.

Was it a Vipassana thing?

It was a crunchy one where they were like, "Here's your journaling prompt," and everyone would take out their notebook to write about being silent. This is a totally frivolous question, but are you into yoga at all, or meditation?

When I came back from my five-day thing, I was like, "I'm super into the Bhagavad Gita now; non-attachment is everything." And that does feel, in some way, connected to your narrator’s line of inquiry in the book.

Should I share my meditation-yoga history? I did two of those Vipassana things in my 20s.

No printed word?

Yeah, the high misery level. The first time I went, I thought of the ending of the movie I was trying to write, Me and You and Everyone We Know, on day two of the nine-day retreat. I had to repeat it to myself every day so I wouldn't forget it, because you can't write anything down. The second I got out, I went to my car and wrote it all down on my map with eyeliner. Just like, "Goddamn it, I fucking held this thing." That's exactly what you're supposed to get out of those retreats—they’re meant to be productive.

The second one I had a cough, and I developed a crush on the woman sitting in front of me. I won't tell that whole story because I told it to Carrie [Brownstein] at the time and she made a Portlandia sketch out of it. But I never told her the most humiliating, heartbreaking part. There's a point in the retreat where you can go up to the teacher and whisper a question quietly. My crush was this short, gray-haired woman, and when she went up to talk to the teacher, I strained closer to hear it. I just needed to hear her voice. And she said, "The woman behind me has such a percussive cough, and I’m really struggling."

I’d been holding it together for days, and the tears just fell one after another. I stood there silently, thinking, this might be the worst moment of my life.

You sat there and were present with it.

Yes. Later I did some other retreats, and sometimes I had a sitting practice but mostly not. And then I took TM, which always seemed a little Scientology-like, because I knew so many actresses who were into it. All I have to say is that it’s been incredibly helpful. I'm not a proselytizer. It feels like the cartoon image you have of what meditation's gonna be. It’s what I was doing before we started talking.

Oh, okay.

As the introductions were happening, I suddenly realized my energy was dropping. I slumped into a weird position, and you were so sweet, you were like, "You're a star!” [because you thought I was nervous]. I wasn't quite doing TM, but I was trying to get centered, like, "Even though there's all these people and they're talking literally about me right now, I can drop into my core, deeper self."

I love that. It’s making me think about what you said about stepping out of the story of writing the thing, and just doing it.

But I wanted to tell you—I was just in Milan, where you had this incredible retrospective. I was there with a friend of mine, an Italian writer. She's an incredible writer and an incredible person but sometimes our conversations are a little tense because I think she feels—correctly—that American writers, and English-language writers, have so many more opportunities than writers in most other countries. Even in Italy, there are residencies that American writers have access to and Italian writers don’t. So I didn’t know if the exhibition would tap into any of that tension, but when we came out I was floating. And I looked at her, and I saw that she was floating, too. She said, "Sure, there were parts where my envy kicked in, but Miranda July always makes me feel like I didn't realize what I was allowed to do." I think that's the highest compliment. You make so many people feel that way. ♦

This conversation took place on May 29, 2025, for the paperback launch of Miranda July’s All Fours, co-presented by Pioneer Works and McNally Jackson Books.

Subscribe to Broadcast