In and Out of the Frame

Charles Atlas may not yet be a household name, but one suspects that this iconic maker of moving images—already a legend in artistic circles—will one day be regarded as one of our most important artists of the past half-century. From Atlas’s earliest efforts as videographer-in-residence for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company in the 1970s to his more recent, large-scale installations exploring mathematics, few artists have so shifted the terms of video-making in art and culture at large. At a time when performance was typically documented in straightforward fashion, Atlas took creative liberties in consultation with his subjects. He expanded the context of performance by moving the camera, shifting the action offstage, and using other effects that would forever change how a performance could live beyond its time. Moreover, through extended portraits of New York’s most forward-looking art communities, Atlas has for decades broken down distinctions between artist and viewer—and between artist and artist—and presaged the ways that self-generated images and media, today, are transforming us all.

In The Mathematics of Consciousness at Pioneer Works, Atlas returns to his archive to present edits of previous artworks, each projected onto one of 26 window bays in the building’s massive warehouse space. He meditates on how the brain operates through cryptic, voice-over narration, while also approaching his own archive as a collection of “synapses,” joining together clips from the past in fresh ways. Viewers are prompted to examine the functioning of their own memories and brains, and how the apps we use to consume digital videos may be restructuring those operations now. Shortly after the show opened, the writer and curator Tim Griffin—who worked with Atlas while Executive Director and Chief Curator of venerable New York art space The Kitchen—sat down with the artist to discuss living in, and making art for, this moment; his turn to science and consciousness; the role of the archive; and TikTok breaking the boundaries of the frame.

- The Editors

Charlie, how would you describe what you originally sought to do with this project? And where did things land?

Well, I always start out with: what are the givens? And the givens were the wall—its architecture and structure—and building the structure of the piece into the structure of the space. So I did a lot of experiments dealing with the window versus the wall, and just making things in these different categories. That was nearly a year's work, and I didn't really start putting it together until a month before it was finished. I mean, I had all the bits, but I had no idea how it was going to come together or whether it was going to make any sense or what it was going to communicate. It was as much a mystery to me as it was to anyone else.

Is this the most challenging space you've dealt with?

Definitely, for a lot of reasons. Because, first of all, we started from scratch. I mean, Pioneer Works had never done a piece on that wall, so they didn't even have a diagram of it. It took me six months to get one as a template, and then it wasn't really right and I had to do it myself, I had to get projectors in and do live things off my computer to adjust it to the windows, before I could even start working. That took a long time.

I’m struck by how your thematics may be far-reaching, and yet they always begin with the literal. Here, you are dealing with highly speculative, even poetic—to my ears—scientific theory, for example. But you still open your thoughts with the actual room, or, in other previous work, with the camera as it is set in a room.

The structure is always the first thing when I begin a piece. I mean, where's it going to be? All of my installation pieces are tailor-made for the first space they're shown in. And if they’re reinstalled, they’re adapted from there.

We were talking once, years ago, when I mentioned how, even in your earliest videos of dancers, you seem a part of the choreography. You’re on the scene and often in motion, never totally pretending you aren’t there. If I remember rightly, you replied that such positioning actually allowed you to parse what the camera perceives.

In this piece at Pioneer Works, you explicitly take up human perception and its limits. But I’d argue that your video-making has already offered such a model through the camera interfaces you create. What are the camera's shortcomings? What are its interpretations of a 2D medium heading into a 3D space?

In all the video pieces and collaborations I've done, there are givens: how many cameras, where can they be placed, and what kind of space does that give for the performance?

I have to say, when I was working with Merce [Cunningham Dance Company], we would usually go on advanced trips to the spaces that we were going to perform in, and we would look at the space and [Merce] would decide what pieces could be performed there. That gave me a background in where to start. I mean, he always liked limitations, so that was a given. It wasn't like a free field of whatever you wanted to do, wherever. It was taking a specific space, or a specific problem, and then dealing with that.

Do you end up seeing the limitations in your pieces, once they’re presented to the world?

Once they're given, they're not limitations, they're just givens.

[Laughs.] Given the context of The Mathematics of Consciousness, I’ll just go ahead and say that's very Kantian of you. On some level, you're suggesting that what we see is steeped just in our categories of possible experience.

I'm not that intellectual. I just make something out of whatever, however I do it. I don't start with an idea, usually. I just begin and see what comes up, and I hope that it makes sense to someone else. With this piece especially, when I finished it, I wasn't sure what it was. I mean, I knew what the elements were, I knew what I had done. But not how it is as a piece, and what people get out of it. The kinds of responses I've heard from people are that it's hypnotic and engaging and thought provoking. That's all I really want people to get.

Right. When it comes to that hypnotic quality, it's interesting for me to consider the geometric animations that you put forward, and how your interjections there underscore the malleability of our perception of space and illusion. In the [video’s] monologue, there's even a discussion about how what we see is only what we ourselves are putting into the world, on some level. Such limits, and thresholds, are made visible in the video’s figures, as they move from abstract to figurative and back, in tandem with the speculative voiceover. Your video asks viewers to process this experience, while they are actually having the described experience in real time.

One thing that I think of, that came to me when I was doing the 3D movie Tesseract, is that it's all dependent on the brain. We don't see with our eyes. We don't hear with our ears. We hear and see with our brain. And that's a mystery.

I've always been interested in the fact that our brains didn't develop the ability to see molecules, because it wasn't an evolutionary advantage for survival. That’s something I was thinking of, in terms of perception—the fact that we've discovered these things that we wouldn't have thought of, except by rigorous experimentation and thought.

What would you say has historically driven your interest, or prompted your interest, in science and the brain? Historically, your work is perhaps more widely associated with dance, or with downtown culture, wherever that is on the globe.

I'm a big science fiction fan. That was my entry into science.

Really? Which books or films?

Oh, my favorite one in recent years is The Three-Body Problem. It's a trilogy by Chinese science-fiction writer Liu Cixin. It's really astounding. It starts in the Chinese cultural revolution and ends in the end of the universe.

What's alluring about science fiction for you?

It provokes awe and wonder.

It also puts a different spin on our understanding of subjectivity, really, as it can begin to fall away—whether in the face of scientific rationalism, uncanny AI, or futuristic renderings of an alien cultural landscape. Science fiction offers us a way to think through radical change in the present. There's something of the sublime in it all. How would you compare that disposition to, say, the limits that you experienced or understood working with Cunningham? Is there an analogy to be had?

The work that I did with Merce, it was really like puzzle solving, like figuring out what are all the possibilities of a given situation, and then exploring them in a systematic way.

The work has you firmly situated in that context. And yet one of the most beautiful aspects of Cunningham’s work is also how no one can see it all. There is always something beyond you, whether in time or in space.

Along these lines, when I was watching this work, bearing in mind as well what you did at The Kitchen with the past is here, the future are coming—where you presented videos from your archives, but only to anticipate how later generations might encounter your work—I wondered whether the science here offers a kind of distancing device. I ask because, when you look at what is actually being projected in the windows at Pioneer Works, it's pretty intimate—in so far as you're talking about the organization of your memory, the organization of your time, people from different moments in your life.

You've spoken elsewhere about how the very medium of video provides you with a model for these endeavors—there are time codes, and editing, and ways in which structure and unexpected juxtapositions trigger memories—and here that is plain to see. It’s deeply moving. You're going through your own archive and constructing personal histories. Once again, the philosophical conceits have immediate resonances.

Yeah, I like the selection that came up. In some ways, I had to put in memories of the people that I've worked with, without that being the theme of the whole piece. I'm happy with the way it represents my output. It's not completely representative or exhaustive or encyclopedic, or anything like that. But it gives a flavor of a lot of the things that interest me, and that I've done.

It is always remarkable to see Cunningham there. But even more striking to me is that you immediately moved from his full figure to an isolated close-up of his hand. Again, we are aware of the limits.

Things in my work might seem idea motivated, but there's so much that's practical in my solutions. Of all the work I did with Merce, there are hardly any where Merce is himself in it. And the parts of Merce that fit in the windows in The Mathematics of Consciousness are again even more limited. So it's really more practical. I mean, it was part of the piece, the closeups I've done of Merce's joints. And I've done other kinds of very close work.

Practicality, you say. So, I’m going there: TikTok.

Uh-oh. TikTok. Yeah.

You’ve told me before that you love to pass the time in doctor's offices by looking at TikTok. And you end this video with a fantastic, but very unexpected, sample of people dancing to Lizzo’s “It’s About Damn Time,” as a kind of coda. What prompted you? The dancers are so good. But we could also go there with the double entendres. There’s Time and then there’s time.

I was just thinking about representing the things happening in my brain, and I'm a TikTok addict. And so I thought, I have to put that in, in some way, because that's the most contemporary way of interfacing video and dance. It comes as kind of a shock at the end; I like the way it works. I think people are really surprised. It’s like the principle is to leave them laughing.

I went through tens of thousands of those dance versions—well I didn't go through tens of thousands, but I went through a lot—to pick the ones that I wanted.

And which ones did you find yourself wanting?

Well, the ones that are in there. It's all from that one little piece of music. It's a dance challenge that I don't know who started on TikTok. I'm very interested in that changed aesthetic. My aesthetic for the whole time I've been working is how to frame—what to frame in and what to frame out. And always having complete frames and very clean decisions about what's in and what's out. Nowadays, it's just whatever. It's just about the energy. The hands go out, feet go out, it doesn't matter. It's a very interesting development. I think it's just the availability of cameras, and everyone doing their own videos all the time. It’s a different way of thinking about material, and video really.

Could you say more about that trajectory and what you make of it?

In the very beginning of my work with dance, I was all with Merce, and we always filmed the complete body, because that was one of the things that wasn't in previous ways of recording dance. And then at a certain point, when I started working on television for WGBH, I realized that the language that I was working with had to do with closeups and engaging. I started doing shots that cut off the legs, but still were very specifically framed. It was either a knee shot, or a headshot, or something specific. Like the isolated hand in this video. And this is a new development where none of that matters. And it's more about the energy of the performance.

It’s interesting, in your work, you've been organizing your archive, or looking at how there are so many different ways to organize the archive, on the one hand. And on the other hand, in more recent pieces, you’ve taken up how other people will see your work, the next generations, and this different aesthetic. There is a kind of paradigmatic shift that you're describing here, which this TikTok introduction makes some acknowledgement of.

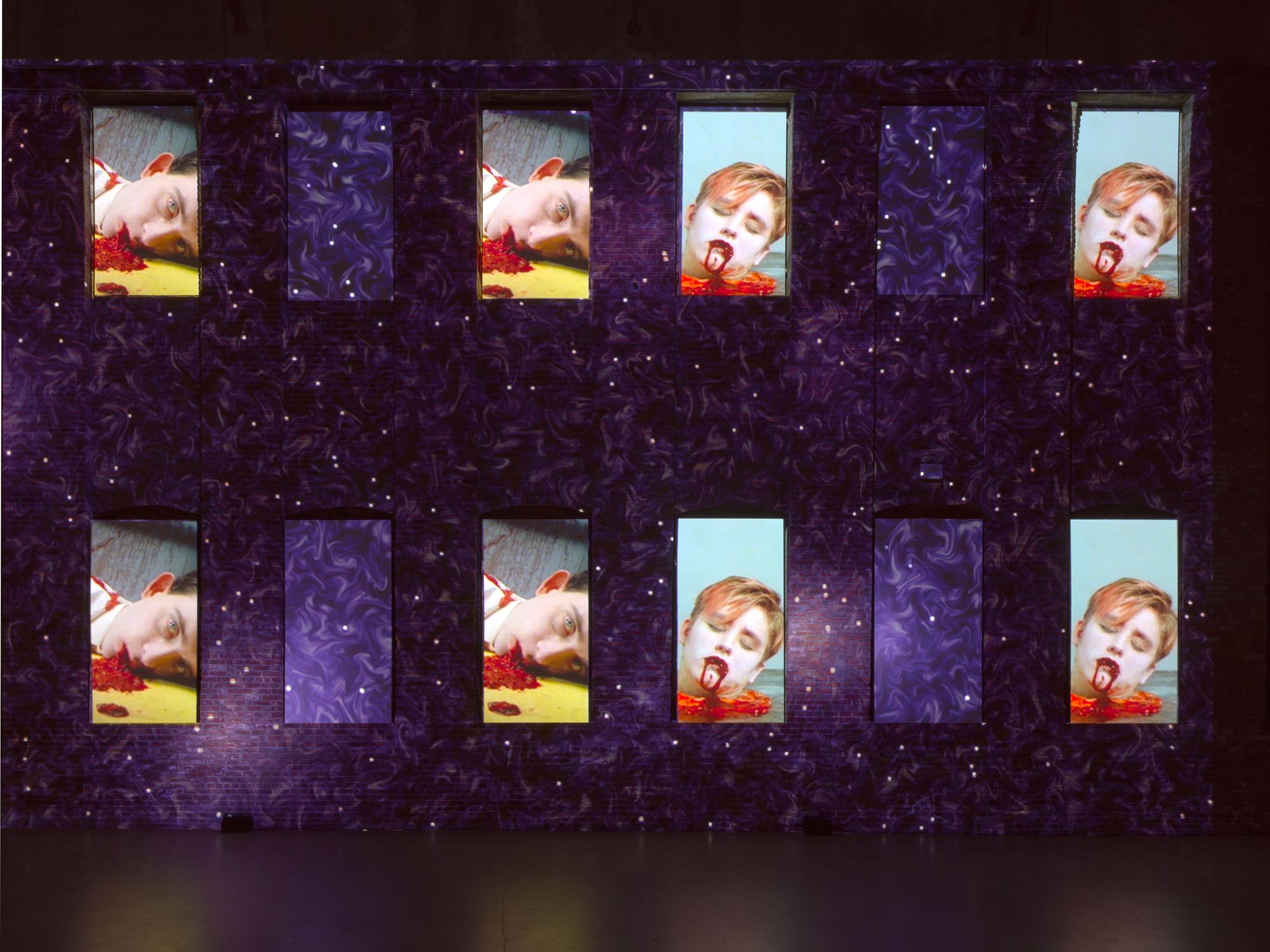

Installation view of Charles Atlas: "The Mathematics of Consciousness" at Pioneer Works, Brooklyn, September 9-November 20, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Pioneer Works.

Photo: Dan Bradica

Installation view of Charles Atlas: "The Mathematics of Consciousness" at Pioneer Works, Brooklyn, September 9-November 20, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Pioneer Works.

Photo: Dan Bradica

Installation view of Charles Atlas: "The Mathematics of Consciousness" at Pioneer Works, Brooklyn, September 9-November 20, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Pioneer Works.

Photo: Dan BradicaI've always wanted my work to be relevant to the current culture, but I can see that things are going to move on after I'm not here anymore.

Do you already feel that kind of distance? In a sense, your work already contains so many distancing devices, even if just by offering a monologue meditation on the operations of the brain—that’s something personal, and not. You could also point to the conceptual art tenet that once the artwork is out of the artist’s hands, it’s already moved on and has a life of its own.

I would say I'm very invested in coming up with unique solutions to different problems, or conditions. It's not apart from me. But probably something unique is my sort of OCD about everything, about details, and having a logic behind things. I mean, there are probably things that I don't perceive about my own work that other people do.

I did a film with William Kentridge. He said that the artist's job is to make the work, not to interpret it or know what it means. I like that idea, because it takes the responsibility off me.

I suppose this is where science and art really come together here. You're attracted to science, but largely because its speculations are so rigorous that they reach a failure point, at which we don't have any answers—only more questions.

I'm still fascinated by all this quantum mechanics, and quantum field theory. But I don't think I'll ever understand it, really. I guess part of the OCD is wanting to understand the absolute truth of reality, and that involves going down to the quantum level, which we'll never be able to see, and I'll never be able to understand because I'm not a scientist. But I'm interested in that mystery.

In the work’s monologue, one of the first mind-benders arises when you start to explode questions of scale. Interspersed among videos from different points in your life, you dial out and describe a cubic centimeter of the brain, and then the universe, noting how both obey quantum physics.

That's the whole idea about the mathematics of consciousness, that consciousness is physics based. Everything is physics based. There are four theories about consciousness, and one of them has to do with mathematics.

I mean, it's just ideas, and hopefully it's provocative.

But you wrote the monologue?

I did a lot of research and adapted quotes from various places. The goal was to make something that a really ordinary person would be able to understand, so it was challenging to get the language right. And also, it's not that the viewer can understand it from reading it; they just have to understand it from hearing it, without seeing a face. That's even more challenging. It had to be pretty simple and direct. And even if it ended up talking about mystery in some way, it still had to be easy to understand, and not off-putting.

I want to come back to the literal. In the monologue, you're pointing out into the world, and then you come back to, on the one hand, how a camera works, and how video-editing offers a model for the organization of the world. And on the other hand, on a really personal note, there's you working with your archive and your personal investments. It's funny, you’re talking about quantum physics, but then it's also just a meditation on art making, and what your experience has been.

That's true. If I didn't include the archive and I just made this all abstractly, it wouldn't have been as meaningful. I’ve done pieces that are completely abstract, but this one wasn't going to be. Of the year it took to make the piece I was thinking about: how am I going to communicate ideas about math and science without putting them in words? And how am I going to find enough material that suggests that, without explaining it? This is the solution that I ended up with.

Do you believe that every act of memory is, to some degree, an act of imagination?

Yes, because it's the same. The part of the brain that’s about memory is the same part of the brain where predictions about the future go.

Oh, that's actually a real Janus face there. In terms of a sense of dispossession around the plumbing of consciousness, there’s the phrase [in the video], "When at the end of consciousness, there's nothing to be afraid of. Nothing at all."

I love that.

That's a hardcore statement. What prompts that inclusion, and what's its role here?

Because everything is consciousness about being alive. I mean, that's how you know you're alive. And when you're not alive, there's no consciousness.

It creates this whole other existential context for the work. In this world, everything's about you, and not. However personal your experience here is, it's also just something unfolding.

Yeah. I mean, it's sort of my world view that there's nothing else but now. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast