Rip it up and start again

New York City, 1988

“I hate faggots.”

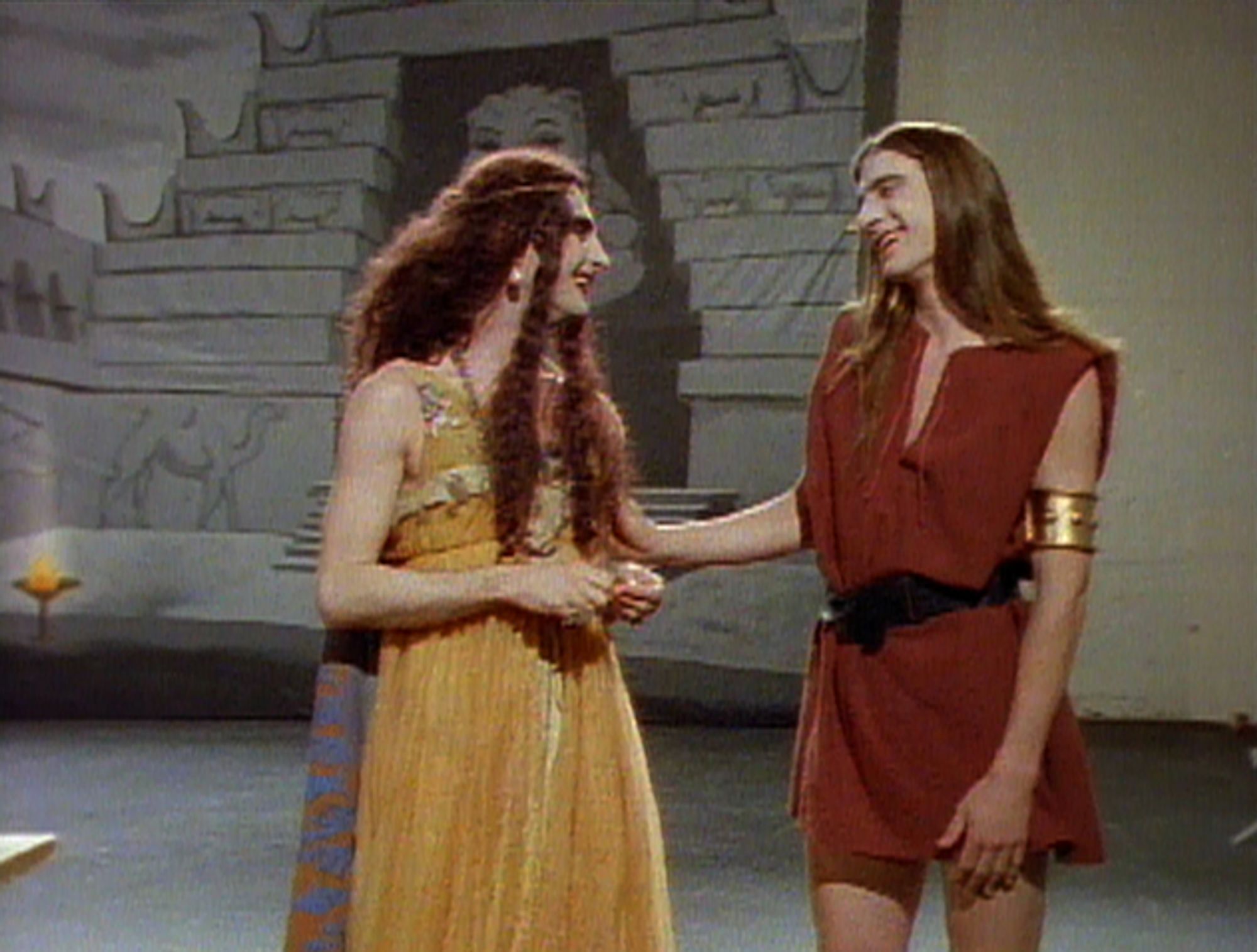

A white male face fills the frame. He’s wearing a button-up shirt, and begins a homophobic rant that quickly veers into Islamophobia. The rage and intensity of his speech build until a shot rings out and blood erupts from the man’s mouth, splattering the camera lens. Another shot: a woman, framed from behind, gazing upon a theater backdrop that’s been crudely painted with a statue of a jovial deity. A note from a piano sounds, and she pivots to reveal herself to be a drag queen. We cut back to the dead man: more gore flows from his mouth, pooling in rivulets on the table in front of him. A rottweiler barks.

This abrasive mélange of scenes makes up the first two minutes of Son of Sam and Delilah (1991), a pivotal title in the five decade-plus career of Charles Atlas, which began with 16mm and video compositions produced within the Merce Cunningham Dance Company (the two-screen Torse (1977), green-screen Blue Studio: Five Segments (1976) and monitor-based Fractions I I(1978), etc.). He would later collaborate with Yvonne Rainer, Marina Abromovic, Douglas Dunn, Karole Armitage, and—importantly for the evolution that would beget Son of Sam and Delilah—Michael Clark. Son of Sam marked a key departure from Atlas’s earlier, more documentation-centered works, however. Where prior titles emerged from creative dialogues with a central performer or choreographer, this piece didn’t grow from a one-on-one collaboration. And the dancing we see on screen tends towards casual club-style movement, rather than elevated choreography.

Son of Sam and Delilah is a narrative woven together from a series of scenes improvised with a trusted community of creative club performers. As the title suggests, some sequences feature them playing New York serial killer Son of Sam (David Berkowitz), who was indicted for eight shootings in the summer of 1977 and claimed demonic communion with his neighbor’s dog. Others riff on the biblical tale of Samson, the chosen man of God, whose love, the Philistine temptress Delilah, strips him of his power by shearing off his long mane of hair. These images pulse across other scenes in the 27 minutes of videotape that might first appear wholly inchoate, gratuitous, or senseless. Yet they dialectically build, creating a piqued space of celebratory release and loss through emotive association: a leather-clad biker (Son of Sam) roughhousing with his dog; a drag queen (Delilah) singing opera; two avant-garde dancers in slips hacking violently at life-sized dummies with cleavers; another drag queen burning toast. It’s a classic cut-up. Meaning arrives in the interstices, as we piece together all of this discord.

The performers were Atlas’s friends, figures from an underground scene in the East Village which, in the 1980s, was exploding around venues like Danceteria, Club 57, and The Pyramid Club. The Pyramid held space for outré theater pieces and wily drag shows—often one and the same—and was where high minded critique met lowbrow send-ups of popular entertainments of the recent past (Psykho III: The Musical and Ballet of the Dolls are just a couple examples). It was at The Pyramid that Son of Sam’s gabby, culinary ne’er-do-well Hapi Phace—the groundbreaking performance artist and nightlife legend—maintained her Sunday showcase, “Whispers Cabaret.” Hapi’s on-screen confidante, Hattie Hathaway, was a member of the band 3 Teens Kill 4 with artist and AIDS activist David Wojnarowicz. She would eventually become The Pyramid’s creative director. Atlas’s Delilah, the renowned performance artist John Kelly, was a regular at Whispers where, performing as the drag queen Dagmar Onassis, Kelly would vocally emulate Maria Callas and Joni Mitchell with deft precision. And the violent dance troupe is DANCENOISE (Anne Iobst and Lucy Sexton); long before their Whitney Museum retrospective in 2015, they got their start at The Pyramid in 1983.

Atlas’s casting was intuitive, his production notes largely circumstantial: John Kelly had limited availability, so they filmed material from the opera that he had already learned (Camille Saint-Saën’s Samson and Delilah); Atlas met the opening male monologuist in a class for acting on camera (while his scripted ravings are credited to Sexton); Hapi Phace got Hattie involved; the same long-haired actor (Almon Grimsted) plays both Samson and Son of Sam. Like a true documentarian, Atlas let life and the scene around him compose the work even as he brought his own vision to it. (He wanted lots of fake blood.)

It’s clear that these “actors” are largely meant to portray themselves. Dodging a producer over the phone towards the start of the tape, Hapi exclaims, “My rehearsals are always better than the opening night. So, I’m going to save my rehearsal for the actual show.” Many of the performers even keep to their names. But the gaudy excesses of Sam’s stage gore throw camp into the mix and meaning striates into a web of interpretive planes. Son of Sam and Delilah plays up the emotional drama of screen action while laughing in the face of death with overwrought kill sequences. It’s funny. It’s meaty. It’s melancholy. It feels like it’s shifting as we watch it. The thing feels profound.

This intuitive process of casting and assemblage, with its associative quality, was quite prevalent in film and video compositions from this period, in which New York artists were beginning to process the incommensurability of the HIV/AIDS crisis. Son of Sam and Delilah, as Atlas noted in a catalog text, was one such work. “I didn’t realize what the piece was really about until a year or so later, after I had edited it,” he said. “It’s about AIDS. It’s an emotional response to seeing all these people die. That’s why the piece is so bloody.”

In these ways, the video echoes Greta Snider’s No-Zone (1993), a 16mm patchwork film of seemingly random fragments of millennial anxiety. In Snider’s work, an herbalist points out the various plants that can heal and harm; BMX bikers crash and clip over concrete ravines; a train hopper details his survival kit; a hoarder displays scraps of atomic debris; and a first-person memoir recounts the burial of large chemical waste vats in the field behind his home, only to witness them unearthed after some time, swollen to an alarming size. Snider’s work creates an interiority for the viewer, in which we might process all of these disparate stimuli of a world—laid bare in her images—that no longer makes sense. Rip it up and start again. Both works engage their central topics of health, loss, and counterculture in the face of HIV/AIDS, and both do so gesturally and intuitively. The crisis was still entirely too close, too real, too traumatic to recreate these visceral experiences literally. The crisis was first felt from inside.

Both Snider’s film and Atlas’s video are objects steeped in their time, and should really be considered within, or adjacent to, the legacy of a loose selection of feature films being collected under the banner New Queer Cinema (NQC). The movement’s name was coined by media curator and scholar B. Ruby Rich, after an explosion on the film festival scene of “a flock of films that were doing something new, renegotiating subjectivities, annexing whole genres, revising histories in their image.” NQC titles boasted similarly fractured narratives, building meaning through juxtaposition or allegory. They were coming to grips with the horrors of AIDS through the act of filmmaking itself. Todd Haynes’s Poison (1991) intercuts three Jean Genet short stories in a fragmented meditation on queerness, criminality, abjection, and release. Greg Araki’s Totally F***ed Up (1993) was billed as “another homo movie… in 15 random celluloid fragments,” and figured AIDS anxiety as a teen apocalypse only escaped through suicide. John Greyson’s Lilies (1996) contained resonant echoes of Kelly’s melancholic cross-dresser Delilah in its genderplay production set in a male prison. These were films built within and for a community that needed them most.

The media theorist Gene Youngblood, in his book Expanded Cinema, argued that mass culture entertainment works to create an experience incommensurate with that of interior life. “Life becomes art when there is no difference between who we are and what we do,” Youngblood wrote. “Art is a synergetic attempt at closing the gap between what is and what ought to be.” Son of Sam and Delilah is an investigation into this impulse. And like the New Queer Cinema that surrounded it, the video works to forge new pathways of comprehension, communal historiography, and emotional release. In a catastrophic world, we pose questions in the hopes that enough of them might, at some point, congeal into answers, knowledge, or more potent still, a call. Each of the performers in Son of Sam engages in a play of self that collides with what we know of as verisimilitude. Sam’s childlike mechanisms of violence only work to deepen the absurdity of what we take as real. Fiction’s veil is lifted. Or prodded, anyway. These performances stretch beyond the frame of this videotape. They play us versions of self, facing versions of death. They are immortalized.

I was never quite sure what to make of Atlas’s use of the Samson and Delilah parable. In his production notes he explains its deployment as simply “convenient,” as it was a work that Kelly already knew. But things are never that simple. Narratively speaking, sexual undoing is a pretty resonant parallel: in the parable, a duplicitous lover tricks her man into bed, in order to cut short the hair that is the source of his strength. The AIDS crisis felt commensurate, as the virus was transmitted from this very sort of pleasurable exchange. You lied in my face! You cut off my hair! You lied in my bed!, PJ Harvey would sing one year later. The Delilah scenes are certainly the most formal and contained in the tape. Shooting on a sound-stage, Atlas is most ready here to interrupt Delilah’s fiction, with the clack of a clapboard, the inclusion of the backdrop scrim, incorporating a take of Kelly using a makeup remover pad on his lipstick, momentarily muting his delivery of the aria. In the primal scene, which the tape saves as its last, Delilah is draped over Samson/Son of Sam in bed. A visible clip lamp illuminates a painted backdrop of the sun. My heart opens to your voice like the flowers open to the kisses of the dawn. The power of Kelly’s performance is irrefutable. Delilah, in her element, is more than ready. When writing about similar forms of tragedy, Walter Benjamin observed how the potency of allegory comes from its surplus of meaning. And on another look at the tape, there they are! How could I have missed them, this big box of condoms in the foreground on the bedside table, resting there half-opened as Delilah leans in. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast