Cecila Vicuña on Language, Land Art, and Memory

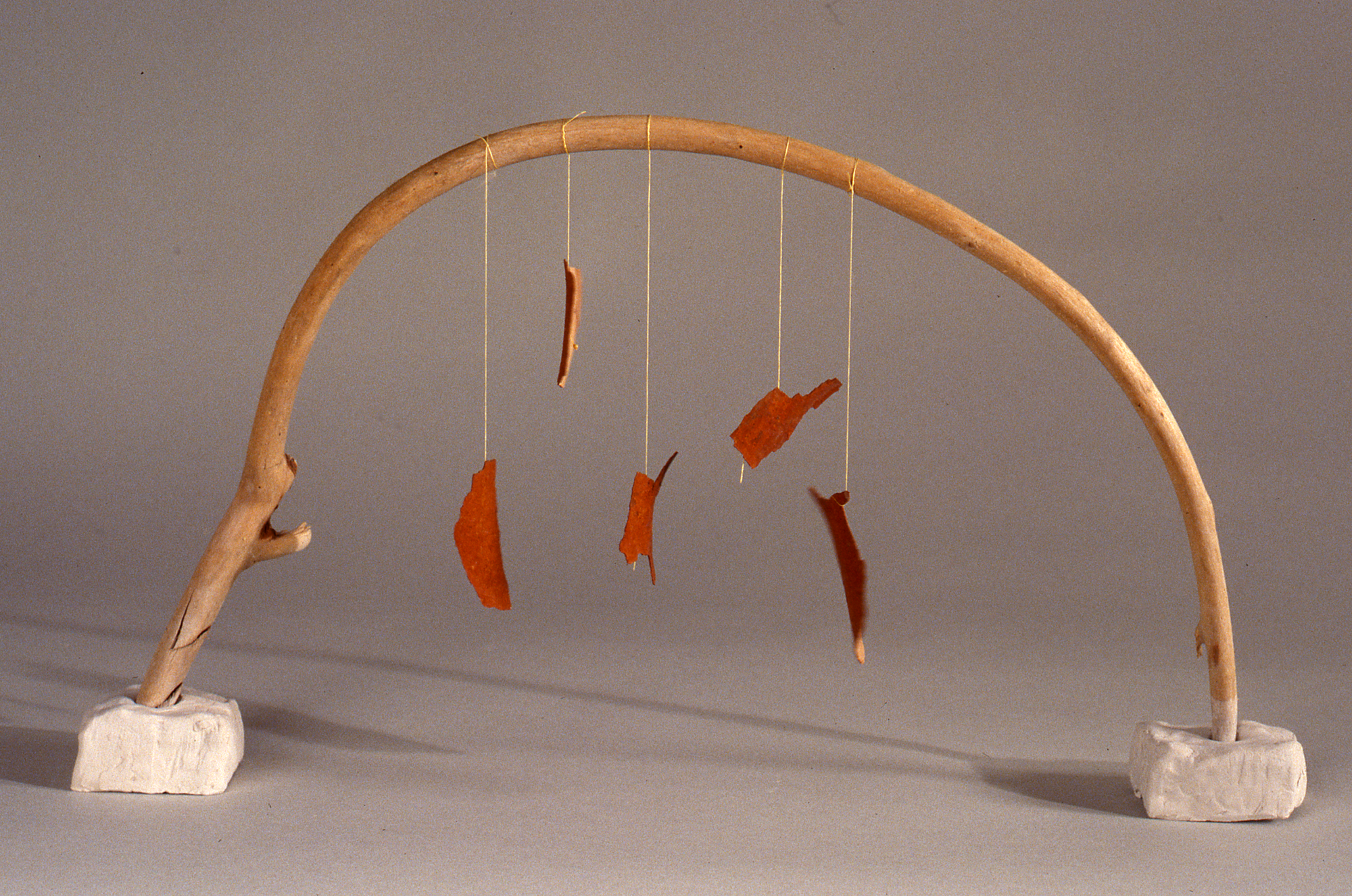

Cecilia Vicuña is an artist, poet, and filmmaker born in Santiago, Chile. She has authored dozens of poetry books: Instan (2002); Cloud-Net (1999); Unraveling Words & the Weaving of Water (1992, translated by Eliot Weinberger and Suzanne Jill Levine), and Precario/Precarious (1983). Her most seminal works engage the properties of ecology, exile, memory, and dissolution. In her most recent major exhibition, “About to Happen,(2019)” that toured five institutions, details the jarring realities of climate change and the denial that looms and obstructs a central organizing principle.

What does activism mean to you now?

There are many ways to answer this question. On one hand, it has everything to do with what I think of activism itself as a way of being and engaging in the world. I think that every human being has to be an activist to secure the continuity of life in this moment on earth. Everyone should be involved in making an effort to construct a better world and conditions. If they’re not willingly going to contribute to the ecosystem of the world they are not deserving of living, and that’s how radical my thinking is around activism. We have scholarship and scientific proof that climate change exists, so what is it going to take for people to understand and participate? Those who are in denial are contributing to the damage that is being done. Then there’s the question of my own personal contribution to the movement, to which I constantly ask myself, "What can an old mestizo woman do?"

In terms of actual activism, I can do very little, and while most people associate activism with actual actions, from my perspective I think knowing what you feel and think about certain movements is a form of activism too. All forms of communication and action are forms of activism as well. In this sense, I’m fully an activist, but in terms of action being a visible material that you can in engage physically, I’m unable to participate in that capacity anymore for reasons of health, age, and Covid-19. But my inability to mobilize on the ground doesn’t make me less of an activist.

In the group show, "Earthkeeping / Earthshaking–Art, Feminism, and Ecology (2020)" you were in at Thomas Erben Gallery, with Helène Aylon, Andrea Bowers, Betsy Damon, Agnes Denes, Eliza Evans, Bilge Friedlaender, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Sonya Kelliher-Combs, Barbara Kruger, Carla Maldonado, Mary Mattingly, Ana Mendieta, Aviva Rahmani, Jessica Segall, and Hanae Utamura, it says, “What makes female artists working today ecofeminists?” What did ecofeminism mean to you in the 1970s and what does it mean for you, today in 2020?

First of all, I never heard of the term ecofeminism in the ’70s, no one was using that term. [Laughter] I don’t know if anyone used the term to classify their art. I was thinking about it–I was doing it in the ’60s–I was working through what I was seeing and feeling while living in Chile, you know and being near the South Pacific Ocean. I was doing and making what people now call land art long before that language existed as a name or concept, and I’m not the only one either who was shaping the movement without using any terminology to define it. Many people who are like me, who are mestizos, who are people who grew up in culture who were also complete hybrids that were colonized but somehow their culture remains in tack.

Do you have any moments when you’re constructing or building something, but it doesn’t feel like you’re making art? Or do you always feel like you’re making art no matter what you’re doing? Like you’re never outside of being in the practice of being and doing something artful.

You phrased this question in a matter that I have never encountered before, so thank you for that. Because you’re pointing to something that is very subtle that escapes most people who only see Art as art is really a Western mode of thinking. If you think about human beings, [laughter] people have been people for almost a million years, and what we understand as art and art history is only a fleeting moment in that story. I remember very well when I was young girl, I had always loved what the west called art. I had an aunt who was also an artist, who was my “madrina.” Do you know Spanish?

[Laughter] Yes, I know a bit of it.

It’s what we call our godmothers. She was a wonderful sculptor. She would always remind me that she has known that I was an artist since I was two or three months old. I was born in July and so by the time spring came around in October, she said she would sit me in the garden or field, and I would marvel at how the flowers would bloom. My parents were gardeners who worked out in the country, so I spent a lot of time with them while they were working. She said that I would dance in celebration of what was happening and that feeling that I had as a baby came long before I had any idea of what it meant to make art.

That feeling that I had is the most deeply human thing. You can see it in insects and in animals, that response to something that is so beautiful in what we call the art historical field, which is beauty, is innate in all living things. It’s how insects and animals choose their mates. How do you think animals choose their mates? [Laughter] It’s the same as us. When I first became aware of being a so-called artist, I was a teenager. There were so many women in my family who I would say were artists, and at the time, my definition of art or what I knew to be art wasn’t being described in the history textbooks as such. And that gave me tremendous joy and pride. Art is susceptible to being defined in ways that are not described by the art historical record. And I’m sure even artists in the west have felt the same thing. The space that exists within the definition of art that has cracks, has openings, and a fussiness about it, is the space that makes what we could understand as art possible. It’s an edge of undefined desire that we must keep undefined.

Do you feel like a vessel?

Of course, we are all vessels. [Laughter] Who isn’t a vessel? We have all inherited a heart that knows how to beat. Are we the vessel for that heart? Yes, of course we are. Are we a vessel for the air that moves through our lungs or the food that passes through our stomach? Of course. But we are not just a vessel–that’s the beauty of it–but we are given an awareness. So, we’re vessels that are of aware of itself. Now we know that bacteria and atomic particles are self-aware. There’s this African saying that goes "we’re all just learning how to become ancestors."

I think of being a vessel in the more spiritual sense where you’re able to not only recognize beauty but you’re able to create it. In some ways, artists are witnesses to beauty, you know. Beauty as pain, beauty as suffering, beauty as language, beauty as life lived. Where does most of your inspiration come from?

I think the question is beautiful, but it is not something that one can answer. In terms of whether you or any human being sees messages in the world, I have written numerous times that I see words as vehicles, and I see them as empty vessels that sometimes appear and then disappear and then reconfigure themselves. They are entangled, they move, and they shift in a lot of different directions. They do all such things. So, when you read about physics and quantum physics especially, the universe is considered information, which means that every form of energy is form of communication or a form of messaging.

Of course, an artist becomes adept at reading these kinds of messages which then becomes a matter of material, which is everything that is around you that comes down to knowing how to use and engage these elements to create something meaningful. For me, I think my inspiration is the attitude and the feeling that you are here to sense, feel, shift, relate, and dance with art. Art is very tricky, it’s like meditation. For example, when you are taught meditation–I don’t know if you meditate–but they teach you something that is impossible to do, which cannot be taught. They say, “focus on your breath without interfering with it.” So how do you do that? The minute you start to think of your breath it doesn’t work–it’s an impossible task.

Subscribe to Broadcast