Diaspora’s Magic Mirror

Natalia Lassale-Morillo, En Parábola/Conversations on Tragedy, Part I, 2024.

Courtesy of the artist and AmantI first met Natalia Lassalle-Morillo by a swimming hole on the river Inabón, in the mountains above the Puerto Rican city of Ponce. I was visiting my friend Mara Pastor, and Natalia was exploring the southern coast of the island with her friend Elisa Peebles. We’d already spoken by phone, after she read the translations I’d made of the poet Marigloria Palma, and used one poem—“Amigo, Esto Que Duele”—as the script for a collaborative film with her students at CalArts. It’s a bitter poem, but intimately so, addressed, as she says, to a “friend”: Because of Puerto Rico / I’m three hundred lightbulbs of illusion gone dead. She challenges the authenticity of certain rituals of grief—in the line behind the coffin, I wept if they wept—and proposes alternatives that can seem more destructive than creative—let’s set the sea on fire.

Sometimes, reading the poem out loud in mixed company, I’m afraid that channeling her political despair, her passionate disillusion, will make me seem reactionary, or unfit to collaborate in the project of freedom—for the archipelago, for the Puerto Rican people beyond the archipelago, or even just for myself. But it is precisely this discomfort that makes the poem liberating, and that has drawn me close to others who resonate with its transgressive intensity. Through the poem, Natalia and I came to call each other “friend,” and to value friendship as a practice of speaking in and through grief. Not grief as the mindless repetition of culturally sanctioned gestures of mourning, but grief beyond discourse: “ticking nerves”; “a howling in the paperwork”; “the blue-green convulsions of the ocean’s laughter.” Of course, sometimes those old gestures still have their place: together, we went to clean Marigloria Palma’s grave in Viejo San Juan. We left her flowers, a pineapple.

We recently spoke while sitting by the ocean at Piñones, one of the last stretches of undeveloped shoreline in the San Juan metro area, in Loiza, a town established by maroons in the 16th century and now populated by Black Puerto Ricans and Dominicans. We talked for a long time, in English and Spanish, in the water and on the sand, smoking and laughing, amid music and shouting, never thinking about how the noise of our exchange might make the conversation difficult to transcribe and translate.

This difficulty, after all, is the natural habitat of our friendship, and of many of the friendships that sustain something we might call the Puerto Rican people. Yet few have the patience to register and respond to the full texture of this dissonance, especially when there’s no guarantee of pleasure in the process or consensus on the other side. With En Parábola/Conversations on Tragedy (Part I), her multi-channel experimental film on view at Amant this past spring, Natalia has decided that this listening is worthwhile even without guarantees. She keeps calling us–“Agua!”–back to the water, where we can rinse our wounds, cool our furies, and let our language loose to mingle in the wordless churning.

(Waves crash in the background.)

“En Parábola” uses Antigone as a prompt for “conversations on tragedy” across the Puerto Rican diaspora. Why did you turn to Sophocles for your structure?

I’ve always been attracted to political, experimental theater. So as a teenager, I rejected the Greeks—I didn't know why I had to learn about what happened two thousand years ago. It wasn’t until grad school that I changed my mind. I was in California, living a very strange and distant diasporic experience: I watched Hurricane María and the post-María disaster in that panopticon of disaster porn. Everything was occurring at once, the logic of time didn't make sense, and my mom said to me, “I think this is a good time for you to start reading Greek tragedies.” So that semester, I read half the canon, and the first one I read was Antigone.

Antigone makes sense to me in the wake of María—an argument over burial rights at a moment when the roads were blocked, the morgues were full, and many Puerto Ricans were forced to bury relatives in the backyard.

Burial rights, yes. And also—who has the right to remember? For me, Antigone is also about this family trying to make sense of life after a great catastrophe. Greek theater was developed as a forum to bring different perspectives together after war: by seeing actors perform stories from your community, you achieve collective catharsis. But it was also a mechanism of state control. So, how do you use the same idea to subvert oppression? I studied theater for more than 15 years of my life, and much of my work reflects those methodologies, even though it doesn’t always manifest as live performance. Especially with this project, I’m interested in the idea that history is a kind of theater and we, as human beings, rehearse it.

Well, Shakespeare agrees with that.

I'm reading Potential History by Ariella Aisha Azoulay, and she talks about how modernism and imperialism are both obsessed with newness, with progress. But in the histories we’ve inherited, we’ve had to reconcile ourselves to the potentials that never had the chance to exist because of colonialism. Our ancestors weren’t allowed their desires and dreams, so we inherit those, too. There’s also something about how the history we’ve learned has been manipulated—especially Puerto Rican history. In the absence of truth, fictions can be crafted to supplant these absences.

Freud has this essay called “Remembering, Repeating, and Working Through,” where he says that when people don’t remember things, they repeat them. To “work through” these behaviors, you’re meant to repeat your memories out loud until the words seem alien. That estrangement creates an opportunity to break the pattern. Glissant, too, talks a lot about repetition in Caribbean Discourse, where he says—I have this memorized!—“Banging away incessantly at the main ideas will perhaps lead to exposing the space they occupy in us.”

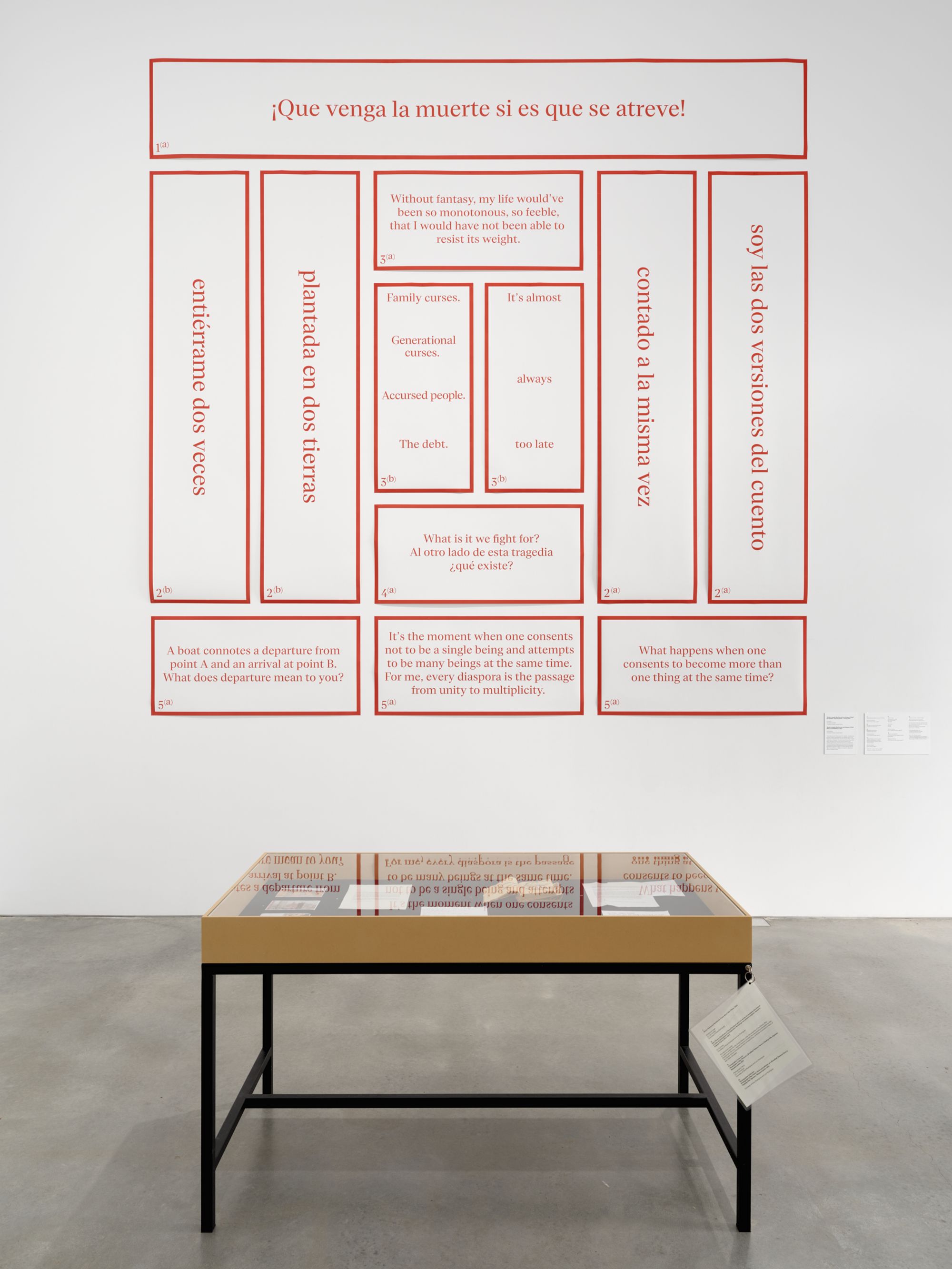

Installation view of En Parábola/Conversations on Tragedy (Part I), featuring works by Natalia Lassalle-Morillo in collaboration with Luis Vázquez O'neill, María Lucía Varona, Emma Suárez Báez, Erica Ballester, Nina Lucía Rodríguez and Raquel Rodríguez.

Installation view of Script for En Parábola, 2024. Produced in collaboration with Luis Vázquez O'neill, as part of En Parábola/Conversations on Tragedy (Part I).

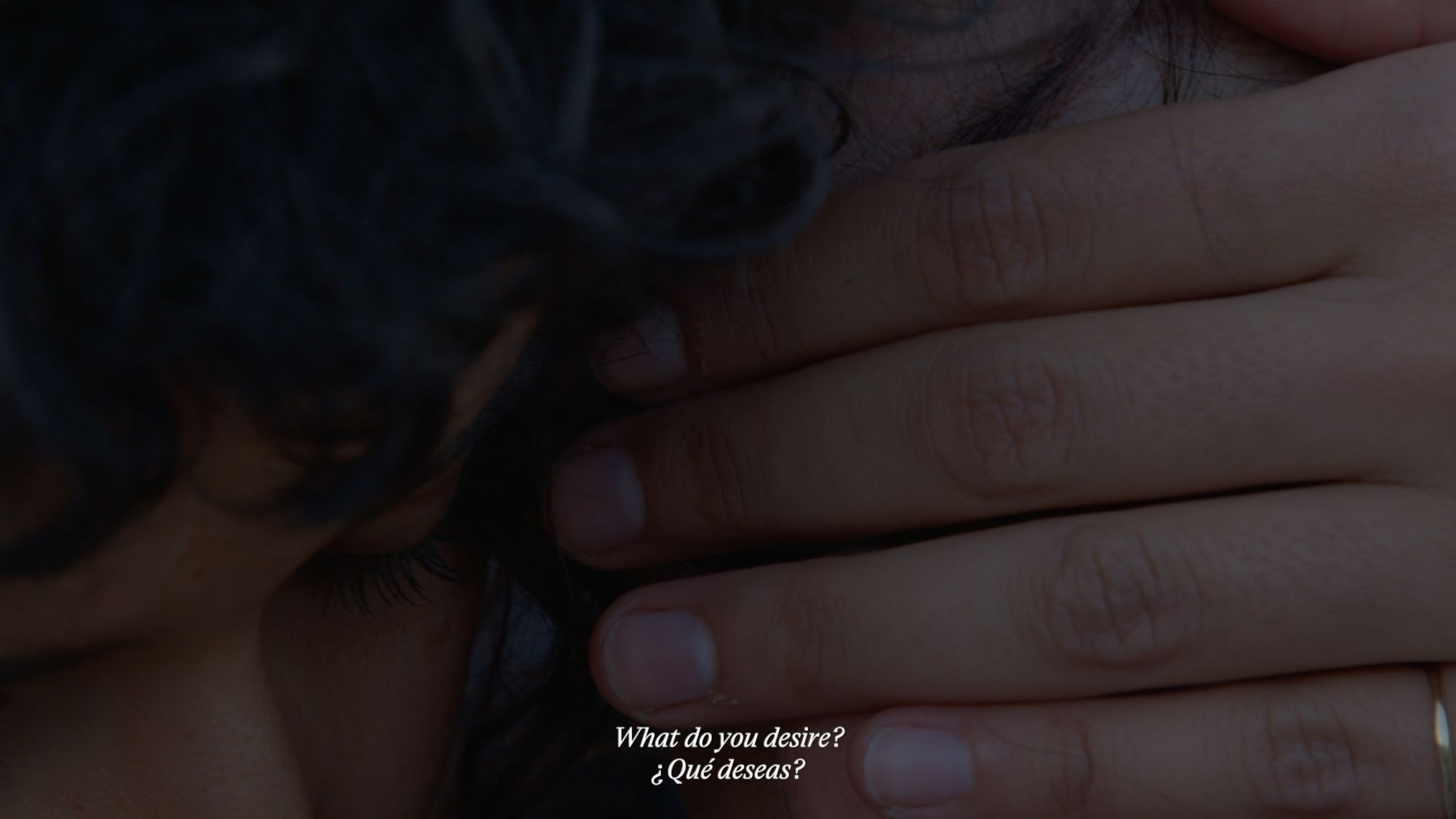

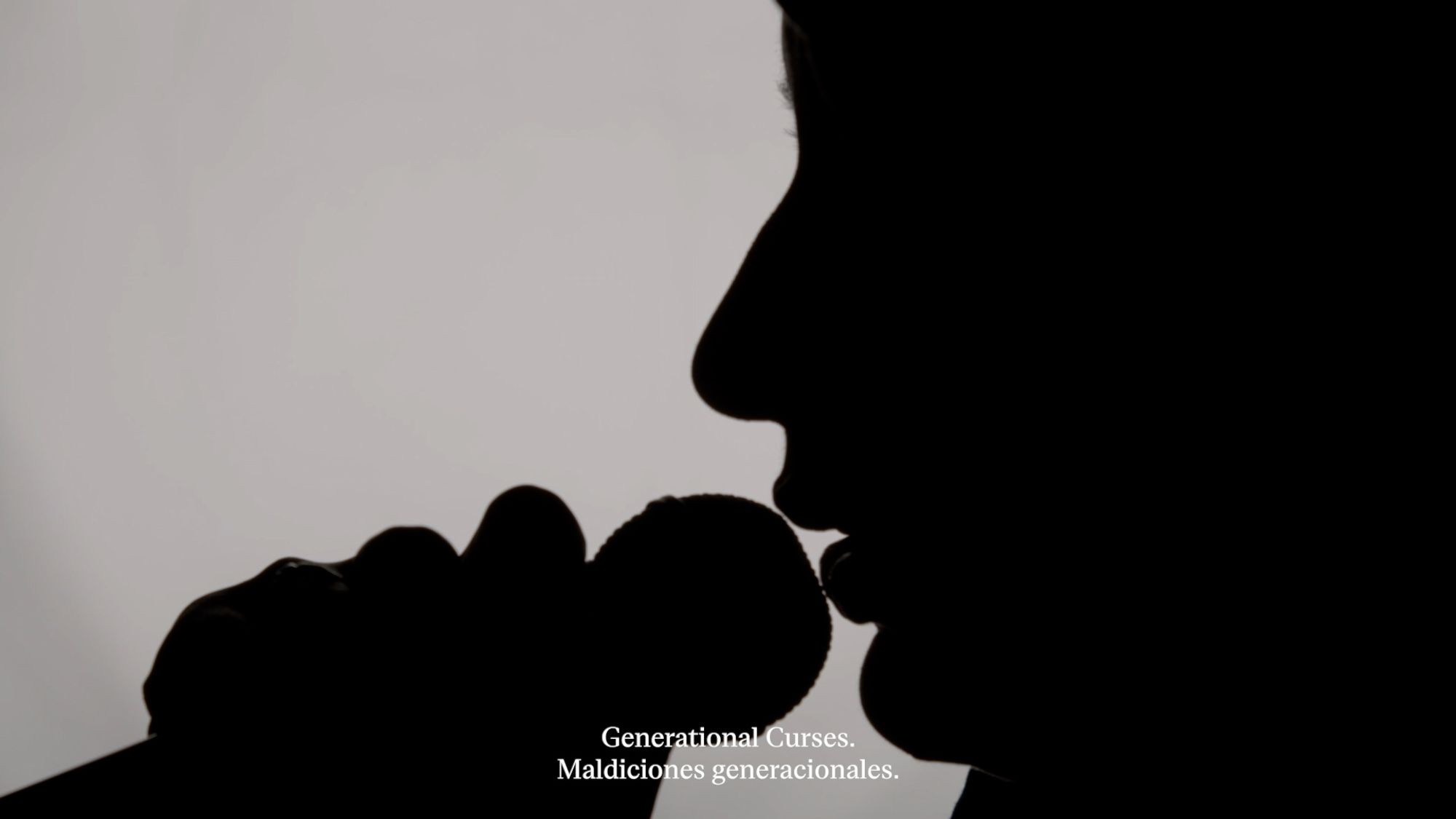

Natalia Lassale-Morillo, En Parábola/Conversations on Tragedy, Part I, 2024.

Natalia Lassale-Morillo, En Parábola/Conversations on Tragedy, Part I, 2024.

That’s really fascinating. It feels true of rehearsal, too, where you do the same thing over and over until you get somewhere. This project is very anchored in rehearsal as a site, an individual and collective space where Puerto Ricans can revise history together, and try things they wouldn’t normally do in real life. Many of the people that got involved with the project weren’t in it for Antigone—they just wanted to share a space with other Puerto Ricans. The people who kept coming wanted to find tools to metabolize their experiences. Raquel, Nina, Emma, and Erica were motivated to explore this story beyond stereotypes. We were in conversation with this ancient myth, but none of us were interested in “honoring” the Greek tragedy. We creolized Antigone.

How did the stories of these particular Puerto Rican women influence the story you ended up telling in the film?

I asked them: what would you do if you could write a different outcome for Antigone? And Emma said something like, “Look, I think Antigone needs to get out of Thebes, because they want to kill her, but also because she can’t deal with living there anymore. So she goes to New York and gets lost in the crowd, and nobody recognizes her, nobody knows who she is, and she has to reconcile this absence from diaspora.” Emma told me she wanted “to liberate Anitgone from Sophocles, from the patriarchy”—which is kind of controversial, because Antigone is known as this great feminist heroine who fights against the state and becomes a kind of celebrity in the theatrical canon. But Emma said: “After you lose your family, do you really want to be a celebrity? I think she just wanted to bury her brother.” When Emma first came to New York City, she worked at The Studio on 14th Street sewing costumes for theater and dance companies, and she proposed a scene in the film where Antigone works in a garment factory. Emma hijacked Antigone’s story with her own.

There’s another scene I love where Nélida walks through the abandoned Domino Sugar Factory site, and it looks so much like a stage to me—a big, empty stage. Maybe that’s partly because of Kara Walker’s famous installation there: “A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby.” But I also remembered how this project emerged, at least at the beginning, from some of your research into the relationship between the U.S. government and the sugar industry.

When I started this project in New York, I was thinking about the communities that began to form when Puerto Ricans arrived in New York before Operation Bootstrap to work in factories. My friend Ali Rosa-Salas is from Brooklyn and she drew my attention to Red Hook: it was really the first Puerto Rican enclave, but now that history seems like a phantom presence. In 1917, Joaquin Colón described arriving in Red Hook on a huge transatlantic ship. That’s how I started obsessing over these coastal zones and the ghost of the Domino Sugar Factory in Williamsburg—dozens of Puerto Ricans worked there!

Who owned Domino Sugar?

At the beginning of the twentieth century it was the American Sugar Refining Company. The first Civil Governor of Puerto Rico was an American businessman named Charles Allen, and he came to Puerto Rico to… you know, set up the colonial base. He retired after his first term and moved to New York to serve as the vice president of the American Sugar Refining Company, which eventually exercised control over a crazy percentage of the sugar production in Puerto Rico.

And the sugar industry’s dispossession of small farms in Puerto Rico was one of the things that pushed Puerto Ricans off the island in the twentieth century, right? I mean, I know that’s true for my family.

Yes—many of the people who emigrated to New York were people who couldn’t find a way to live in Puerto Rico. Many of them were rural farm workers. Maybe they worked on sugarcane plantations, and then they came to New York and started working in this factory, processing sugar that came from the island. I got really caught up in these cycles of labor and migration.

It’s also interesting that so many of those sugarcane plantations were also in coastal zones, with lots of boats, lots of vaivén.

My dad is from Aguadilla, on the west coast of Puerto Rico, and he told me a few months ago that he used to escape from my grandma’s house to cut cane and suck the juice. He said he lived in extreme poverty. Sometimes I think of how my dad’s life represents the ELA—Puerto Rico as a Free Associated State. He left home to enroll at CROEM, a special public school run by the University of Mayaguez, and he became an engineer. He achieved that middle-class dream of “progress.” Those same ideas of progress are haunting us now.

But there are other dreams, too.

We actually quote the Joaquin Colón migration narrative in the film: "Without fantasy, my life would have been so monotonous, so feeble, that I would have not been able to resist its weight.” Sometimes I feel we are so imprisoned by concepts and theories around political status that we don’t really practice our imagination expanded from politics. I’m going to be really frank: I don’t think freedom and self-determination is solely going to come from a change in political status.

Right. Yesterday I was talking about this with the parking guard at the condo in Santurce where I’m staying. He’s Dominican, but he’s lived in Puerto Rico for many years, and he said to me: Amor, la independencia de la República Dominicana es sólo un decir. Like, let’s be real: even the sovereign nations of the Caribbean are colonized. Sometimes I feel like we’re not supposed to say that because it might undermine the Puerto Rican cause. But I also think being realistic about our collective condition helps us think in relation.

What worries me when I try to envision a future for Puerto Rico, including an independent future—and I believe in Puerto Rico’s independence—is the risk that we might replicate the same oppressive colonial patterns among our own people. There’s a lot of work to be done. My own ideas about sovereignty and citizenship are influenced by Ariella Azoulay. She writes that citizenship can’t be tied to the state, and that we have to define it beyond geographic borders. So I’ve been thinking a lot about affective citizenship. And I think that’s what keeps us alive as Puerto Ricans.

It’s actually kind of incredible the way we’re able to develop this sense of collectivity as a people across enormous distances, despite all the disconnection and conflict. Sometimes I actually think of it as a model for other diasporic people.

I feel the same way. With this project, I wanted to create and inhabit a space where we could really practice this affective citizenship, create bonds of trust so that we might take risks on a small scale. I wanted to use theater to cultivate a certain kind of connection that’s unique to the process of rehearsal.

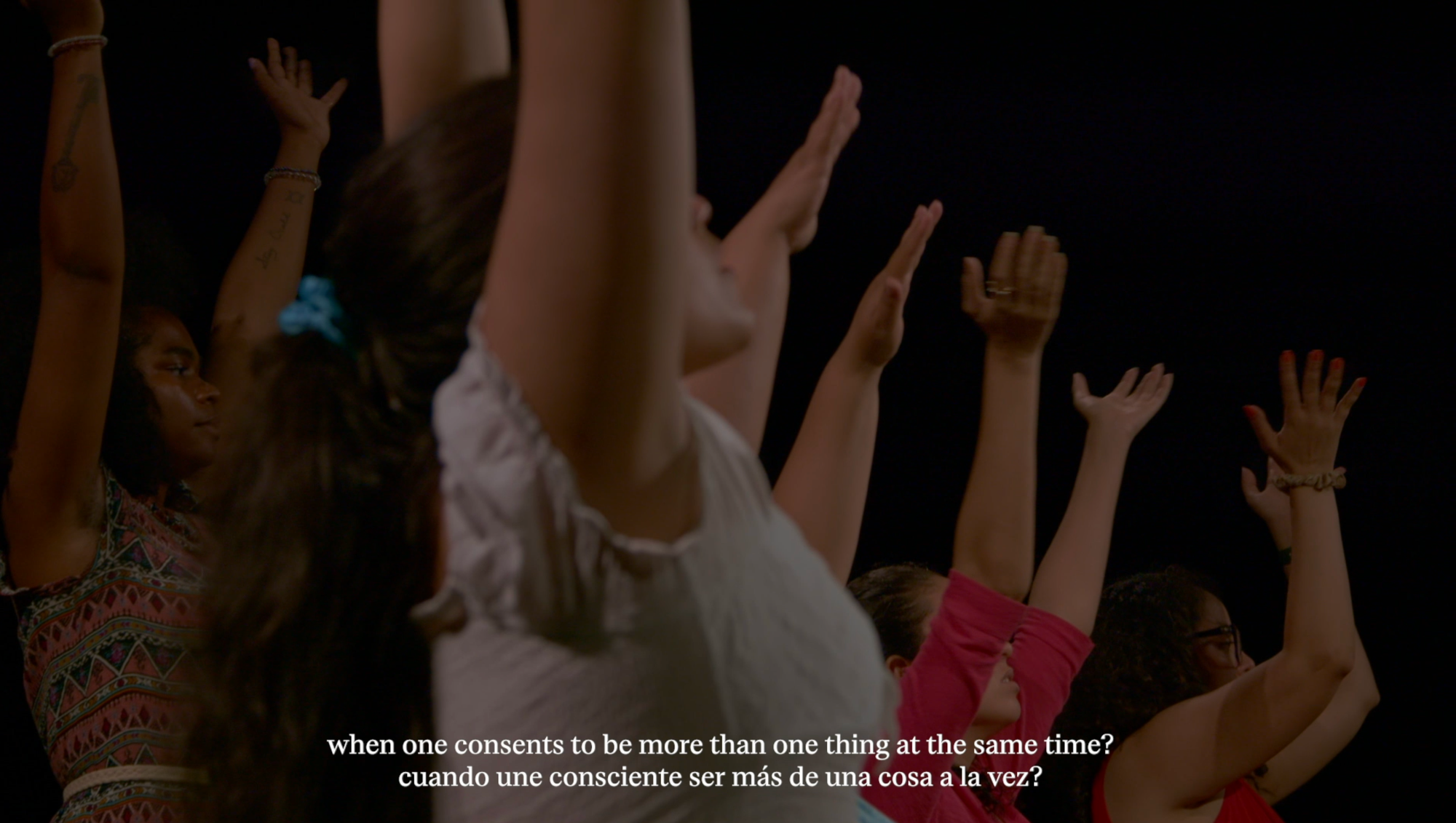

Natalia Lassale-Morillo, En Parábola/Conversations on Tragedy, Part I, 2024.

Courtesy of the artist and AmantParticipating in your rehearsal also made me think about the cultural forms we have in common as Puerto Ricans: el batey, el coro. The batey is a stage that’s more about participation than spectatorship. And the Puerto Rican coro—the chorus of call-and-response in bomba, plena, salsa—is not the same as the Greek chorus. I have so many questions!

It’s ok! We can flow, we can flow.

(They go to the water. They come back from the water.)

I want to return to the word ensayo as a connection between us. How in Spanish, the word for “essay” and “rehearsal” is the same. For me it’s interesting to think about my own journalism as a kind of theater. Recently, I went to Mona Island—a desert plateau between Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic—and as I was planning the trip I sometimes felt like I was setting the scene and casting the characters. But ultimately I wasn’t in control. I was creating a context where something surprising might happen. Which is true of you too, right? We might think of En Parábola as a kind of documentary film. Like, you’re working with people who don’t have a professional performance background, you’re working with archives, you’re working with the sights and sounds of daily life.

Yes! I’ve been working on the mixing for the film and I just sent a note to my sound designer: “Imagine it’s like the metaphysics of mundanity.” My friend Sofía Gallisá said to me that sometimes nothing needs to be invented because reality is already so absurd. I agree with her completely.

Remind me to send you this Manuel Ramos Otero essay called “Ficción e historia.”

I haven’t read it! I would say my work is experimental nonfiction, whatever that means, but again, I’m very influenced by theater. When you’re an actor, you consent to become another person: I, Natalia, consent to become Antigone, with all of my experiences, my sensibilities, my cultural formation. You become a character but you don’t stop being yourself. The hybrid characters that emerge from this contact are so interesting to me, and so relevant to diasporic experience. Because you’re consenting to not be a single being, and become many beings at the same time, like Glissant says. You’re inhabiting multiple places, so you become multiple people.

And that’s why we’re so tired.

Possibly yes!

I mean, when it comes to Puerto Rican migration, that multiplicity often implies physical movement. And that’s tiring too. I know this “freedom of movement” is a privilege of colonial citizenship, but…

Yes, in Puerto Rico these cycles of migration are very unique, right? Each migration has a unique context and it’s not always helpful to compare them. But I’ve learned the great majority of Puerto Rican migrants don’t want to leave the archipelago. So they live with this desire to return. It’s a life en parábola, on the move, crossing oceans.

You don’t have to tell me! Sometimes it really blows my mind that I still desire—and actually sustain—a connection to Puerto Rico even though I grew up so far away, in California. When I participated in your chorus for this film I was really moved by the diversity of Puerto Ricans in that room. Normally, we’re more segregated—by class, by race, by generation, by migration status. But migration is not really a status; it’s a spectrum. I’ve met people on the island whose parents were born in Hell’s Kitchen. Even my own mother: she was born in Washington Heights but she lived in Puerto Rico for five years as an adult. Once you start going back one generation, two, three, you realize most stories are pretty complicated. I feel really surprised, sometimes, that I found Puerto Rico as an adult. “Found” in scare quotes. [laughter]

My voyage of discovery! But you know what I mean? Even the way we met feels unlikely. You read my translations of the poet Marigloria Palma. And why was I translating her? Because my friend Mara Pastor had given me a PDF of Puerto Rican poets from the 1970s. And why did that happen? Because I was specifically looking for an alternative or counterpoint to the narrative I’d inherited. My mother had performed at the Nuyorican Poets Café and she has a lot of legitimate critiques of that scene. But why was she a performer? In part, because her mother was a performer too: she had a radio show in Puerto Rico before she migrated to Manhattan and got normal working-class jobs—the factory, the grocery store, the hospital. I guess I feel amazed by how far these impulses can carry you: how far back, how far forward. Or maybe time doesn’t work like that.

Carina washing her hands in the San Juan Bay, after cleaning Marigloria Palma's grave.

Natalia by Marigloria Palma's grave.

Filming with Erica Ballester and Emma Suárez-Báez at Inspiration Point near Fort Washington Park in New York City.

I do think being diasporic implies a level of faith—faith in something you don’t fully embody. I find that really beautiful, because sometimes I lose faith! Of course, I also know that the diasporic experience—especially the Nuyorican experience—holds a lot of pain in relation to the archipelago. Because some Puerto Ricans in the archipelago have rejected that experience, and still do.

At the same time, the nostalgia of return is complicated, since Puerto Ricans in the archipelago are resisting displacement on their own terms. It's not paradise. I've heard Nuyoricans say they have to buy property here before the crypto bros do. I understand that todxs queremos un Puerto Rico para lxs puertorriqueñxs. But if you buy this dream home, how can it also help those who live on the island and have no escape when the turmoil comes? Within these tensions, I do think there needs to be space for more empathetic conversations about why our connections have been disrupted, and to find a space where we can be in communion with our differences. Someone recently told me that we might look at contemporary migrations as expulsions that require some sort of reparations.

Absolutely. Some Nuyoricans have access to the kinds of salaries that are only available in the imperial core—or at least, speaking for myself now, access to the U.S. media machine, the social connections that make it easier to come and go. But it’s also true that most of us are descendants of poor people who couldn’t afford to stay on the island. The Great Migration was raced and classed in a way that’s distinct from Puerto Ricans who are coming to the city now as adults for white-collar jobs. And this was the first year in American history where there are more Puerto Ricans in Florida than New York. I’ve been joking that I’m going to write a book called Cuando Era Nuyorican… it’s a bittersweet moment.

My first experience in diaspora was coming to study at NYU on a scholarship. A very privileged experience of migration. I was often told: “you’re not a normal Puerto Rican,” which felt horrible and racist. Or they sang to me: “I want to live in America!” Literally West Side Story.

It’s crazy, like: swallow the stereotype or disappear!

I lived in that confusion. I have family in the Bronx, and we visited them when I was growing up, but I didn’t really understand their situation. In school in Puerto Rico, I don’t remember studying the history of the Puerto Rican diaspora in detail, so I didn’t understand how or why these communities came to be. It wasn’t until I moved to Bushwick in 2010 that I started to sense the levels of complexity. Like wow, the nuances here salen por un tubo y siete llaves. I moved into a building with several Nuyorican families, and by the time I moved out, there was only one left. As a student with my own economic precarity, I was part of the population gentrifying the neighborhood. But I made friends with some of my Nuyorican neighbors. They had never been to Puerto Rico, but they treated me like family. They knew I was a vegetarian, and for Christmas dinner they fixed me a Puerto Rican plate with no meat.

There was a woman named Panchita in my grandmother’s building who used to make us vegetarian pasteles. And then my grandmother would mail them, frozen, to California. Sorry, go ahead—

Now, I’m really conscious of my position. I’m not Nuyorican, I’m Puerto Rican from the archipelago, and I’ve lived through multiple diasporic experiences: I lived in New York City, in Miami, and then Southern California. Since I began this project, I’ve been very aware of how community projects can become extractive, so it was a priority to invest time in building familial intimacy. There were two years of invisible work before the chorus could come into being.

Right. I mean, you actually have Nuyorican friends! That’s something I appreciate about you, the organic connection between your “real life” and your work. Where did the idea for the chorus begin?

There’s always a chorus in Greek tragedies. But in this project, the chorus is really comprised of all the people I had the opportunity to talk to along the way, who showed up somehow in the process. On the day we recorded the chorus, the texts and testimonies we read together were fragments from those conversations, interspersed with quotes of Caribbean writers and poets that were important to me and my collaborators in the process of research. Even though many of these people were physically absent, their voices were present. The chorus is an archive of these voices, and I wanted to bring together a group of people who were willing to be the channel for this collective voice.

I loved working with those fragments, because so often, that’s how Puerto Rican history comes to us—in fragments. Maybe it’s in Spanish, maybe it’s English, maybe it’s a rumor, maybe it’s a fact. But on the day of the chorus you had us select some of these fragments at random from a big basket. Like fortune cookies. And then you asked us to find a way to inhabit those words, to hear how they might sound out loud. It was actually really beautiful—and unusual—to experience the noise and mayhem of those moments when we were all walking around muttering to ourselves. You encouraged us to embrace solitude, strangeness, dissonance. Like Glissant says, “Din is discourse.”

That was one reason I asked Xenia Rubinos to guide the chorus. Puerto Ricans tend to go for sabrosura. And that’s great, I love sabrosura. But I told her I didn’t want to push the sound towards any particular place. I wanted a unique sound to emerge from the dissonance of the voices that were present. And if that moves towards a more classic Puerto Rican coro, then cool. But the women at the center of the project were really interested in resisting stereotypes. They wanted to conjure the metaphysical experience of multiplicity.

The textures that we created—like shhhhhh—reminded me of Puerto Rican percussion instruments. The güiro. The shekere. And how those instruments were actually fashioned to mimic or amplify the sounds of nature: wind, rain, the cyclical rhythms of the ocean. But it was also exciting to hear other kinds of music emerge: church hymns, rhythm and blues. I had pulled a fragment that said “I didn’t ask to be born here,” and it made me think of the chorus from the Deborah Cox song “Nobody’s Supposed To Be Here.” So I started riffing on that. Towards the end, when Nina starts repeating the word maravillosa in her angelic tone, I think she’s singing in the same key as Deborah Cox–there’s definitely some melodic continuity. Even though the chorus moved beyond sabrosura, the more idiosyncratic sounds we made later were not, like, totally abstract or culturally neutral.

Right. Once, a professor told me she could see the traces of Mary Overlie’s Viewpoints in my work: the way I work with fragmentation and non-linear time. But the real reason I experiment is because I live in Puerto Rico: trying to make sense of the weather, the wetness, the absences. My experimentalism has more to with that than it has to do with any American curriculum. Another time, someone wanted to talk to me about why I’m interested in collaborating like this, with performers who are not professionals. She said, “There’s something so fascinating about the untrained body.” But I’m mostly interested in what might happen if people did have access to training.

Like, if you’re going to interpret the role of Antigone, you need tools for that. Performance is very intense and sacred and in those heightened states you can definitely transcend grief but you can also trigger traumatic moments. You need tools to bring yourself back.

Natalia Lassale-Morillo, En Parábola/Conversations on Tragedy, Part I, 2024.

Natalia Lassale-Morillo, En Parábola/Conversations on Tragedy, Part I, 2024.

Natalia Lassale-Morillo, En Parábola/Conversations on Tragedy, Part I, 2024.

Natalia Lassale-Morillo, En Parábola/Conversations on Tragedy, Part I, 2024.

Natalia Lassale-Morillo, En Parábola/Conversations on Tragedy, Part I, 2024.

Natalia Lassale-Morillo, En Parábola/Conversations on Tragedy, Part I, 2024.

Natalia Lassale-Morillo, En Parábola/Conversations on Tragedy, Part I, 2024.

And you need time to develop those tools in community. Earlier, you said you were trying to find an ethical way of collaborating. And to me, it’s partly just a function of time. Are you willing to live out those years? I can relate to that feeling from the other side of diaspora’s magic mirror.

Here, in Puerto Rico?

Yeah, exactly. I often think: ok, well one reason the book has taken so long is because of precarious economic conditions and having to finish my Ph.D. at the same time. And I see you contending with similar constraints, having to keep so many irons in the fire. But speaking for myself, I also don’t feel like it would have been possible or ethical to write more quickly. I’m interested in the book, but the book is really a way to stage the kinds of relationships and risks that I want in my life. When I started coming to Puerto Rico as an adult, I didn’t have a project in mind. I had all these unformed desires that I couldn’t even name. The project gives form to these desires and produces its own imperatives. But the project isn’t primary, or there’s a symbiosis that can’t be rushed. Watching you make En Parábola, I’ve seen you embody your own version of the nomadism the film seeks to explore, if not explain.

Yes, they have been so tightly connected, the dynamics of doing and making and living and loving. This project demanded that I stay in touch with several experiences at the same time. Building relationships takes a long time, applying to funding, knocking on a lot of doors and facing rejection. And the demands are ongoing—because this is only the project’s first phase. I think working slowly is necessary. We have to defend working this way. We have years left.

Si dios quiere, as our abuelas like to say. ♦

Special thanks to Katerina Ramos-Jordán for her meticulous, poetic transcription of the live conversation that gave rise to this exchange.

Subscribe to Broadcast