Big Apple Sky Calendar: May 2023

In the 1990s, astronomy professor Joe Patterson wrote and illustrated a seasonal newsletter, in the style of an old-fashioned paper zine, of astronomical highlights visible from New York City. His affable style mixed wit and history with astronomy for a completely charming, largely undiscovered cult classic: Big Apple Astronomy. For Broadcast, Joe shares current monthly issues of Big Apple Sky Calendar, the guide to sky viewing that used to conclude the seasonal newsletter. Steal a few moments of reprieve from the city’s mayhem to take in these sights. As Oscar Wilde said, “we are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.”

—Janna Levin, editor-in-chief

May 1

Sunrise 5:54 am EDT

Sunset 7:51 pm EDT

May 5

Full Moon at 1:36 pm EDT. The Moon is almost exactly opposite the Sun today, so a penumbral lunar eclipse will occur. But it’s of little interest to us, for two reasons: (1) “almost” isn’t quite good enough; and (2) it occurs in daylight, so “opposite the Sun” means below our horizon!

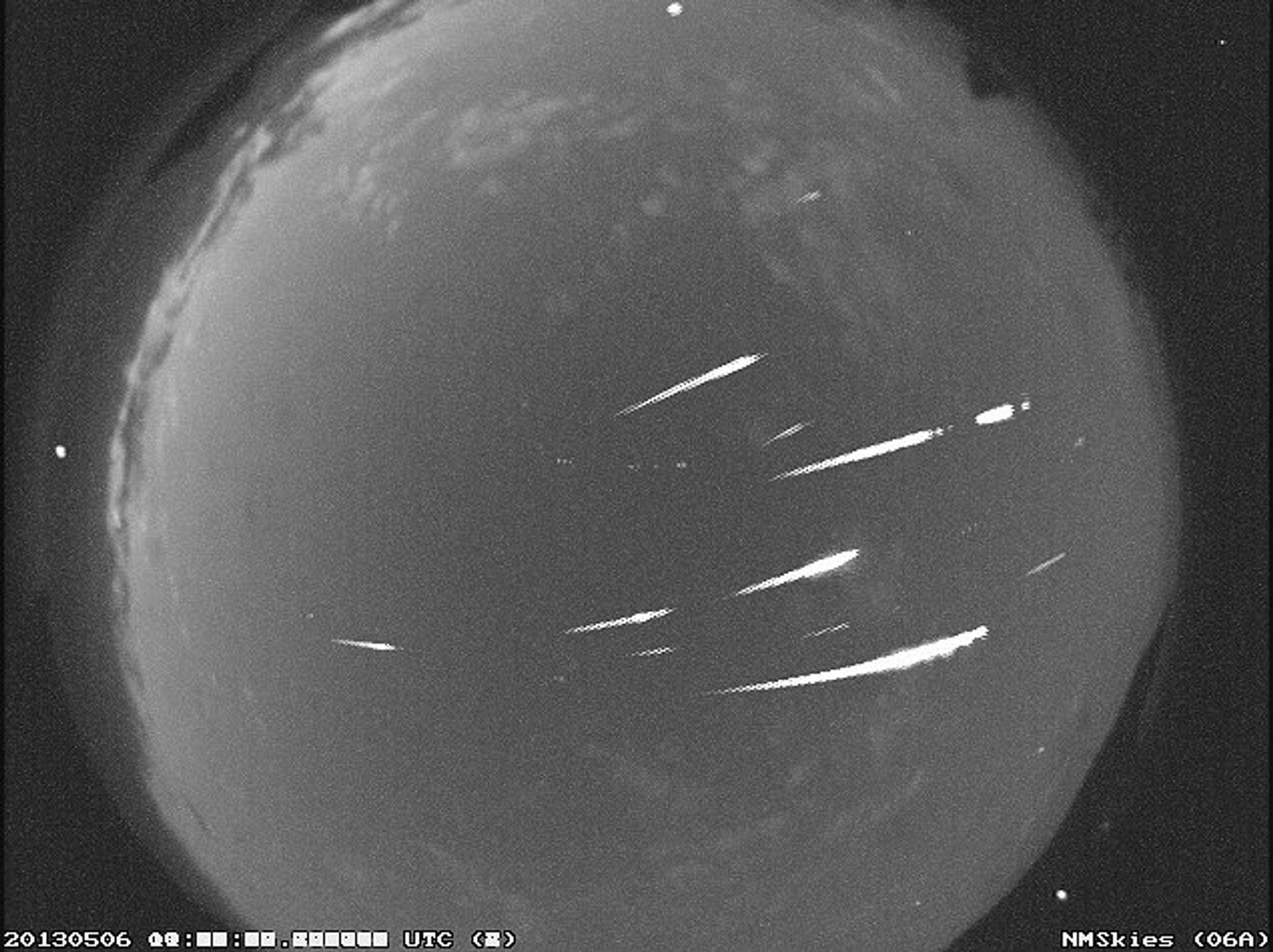

In this morning’s sky (night of May 4th-5th), the Earth intersects the orbit of Halley’s Comet. The comet has been shedding debris, especially when it nears the Sun and heats up, for at least 1500 years. That debris—little dust particles—stays in orbit around the Sun. Like the character “Pig-Pen” in the Peanuts cartoons, the dust just follows the comet around. And the Earth intersects that orbit every May 4th-5th…causing a meteor shower (called the Eta Aquarids, named for the star they appear to emanate from) as the dust burns up in the atmosphere. But despite the two impressive names (“shower” and “Halley”), this shower is usually a yawner. Late April and early May mornings can be cold, and don’t usually offer much reward for the discomfort (except for one April morning in 1775). But if you happen to be stargazing this morning, you might see some meteors from that famous old comet.

May 10

Birthday of Cecilia Payne in 1900. Payne was a young student of Arthur Eddington, the English astronomer whose writing brought awareness of modern physics to the audience of astronomers (not then well trained in physics). Payne could not pursue graduate study in England (Cambridge did not grant degrees to women until 1948), so Eddington arranged for her admission to Harvard. A few years later, she produced what Otto Struve called “the most outstanding thesis the USA has ever produced.” Payne knew much more physics than most astronomers…and was able to show that the Sun was made mostly of hydrogen—an idea much doubted by astronomers at the time, since there is practically no hydrogen in the Earth’s atmosphere. She went on to a long career at Harvard, as the world’s top expert on exploding stars.

May 12-14

On these nights, the International Space Station (ISS) makes evening overpasses of New York City. On May 12th, look generally southeast (SE) from 9:17 to 9:23 pm EDT. On May 13th and 14th, the ISS pops up near your western horizon, passes nearly overhead, then disappears in the east five to six minutes after first appearing. First appearance is at 10:05 pm on May 13th, and 9:14 pm on May 14th. Unlike airplanes, the ISS shines with a steady light—it’s just reflecting sunlight. At 18,000 mph, it’s hard to believe where it is in space. When you first see it, it’s roughly over Kentucky; when it disappears five minutes later, it’s somewhere south of Greenland.

May 13-15

Even apart from the ISS, these are three great nights for evening observing. Venus is the brilliant object in the west—as it has been for many weeks. To its right is the bright star Capella, and above Venus is the red planet Mars. To the right of Mars are the famous twins in Gemini (Castor and Pollux). Get away from buildings and enjoy the spectacle. Since the stars are fixed in position on the celestial sphere, you can watch the planets’ motions (with respect to the fixed stars) from night to night.

May 15

On this day in 1836, Francis Baily discovered the phenomena known as “Baily’s Beads”—the last bursts of sunlight shining through lunar valleys, visible only a few seconds before (and after) the totality phase of a solar eclipse. But remarkably, he observed it during an annular eclipse—an eclipse which just fails to be total, usually by a few percent. I hope he had good filtration! …because it can be dangerous to mess around with solar eclipses during the partial phases.

May 18

Thought to be the birthday in 1048 of Omar Khayyam, the great Persian astronomer, mathematician, and poet. Omar designed the Jalali calendar, still used today in the Middle East for religious purposes, since it’s slightly more accurate (one day error in 5000 years) than our modern Gregorian calendar (one day error in 3300 years). But he is best known for his beautiful poetry—the Rubaiyat. It has been published in many versions and many languages. In 1865 Edward Fitzgerald published an English translation which became a literary tornado, spawning hundreds of re-printings and translations into yet more languages. It even enchanted me at age 15, when my (voluntary) reading was mostly about baseball and war.

May 19

New Moon at 11:55 am EDT.

May 22-24

On these nights, the waxing crescent Moon glides through the assemblage of planets (Venus and Mars) and stars (the Gemini twins, Castor and Pollux) in the western sky during evening twilight. A really beautiful sight, about an hour after sunset.

May 27

First quarter Moon.

May 28

The total solar eclipse on this date in 585 BCE was perhaps the most consequential in history. According to several famous (but not necessarily independent) sources—Herodotus, Pliny the Elder, and Cicero—it stopped a long-running war between two Greek city-states, AND was predicted in advance by the Greek astronomer Thales. Most modern historians do not accept either claim, but scolding Herodotus (“The Father of History”) is usually not a good idea.

May 29

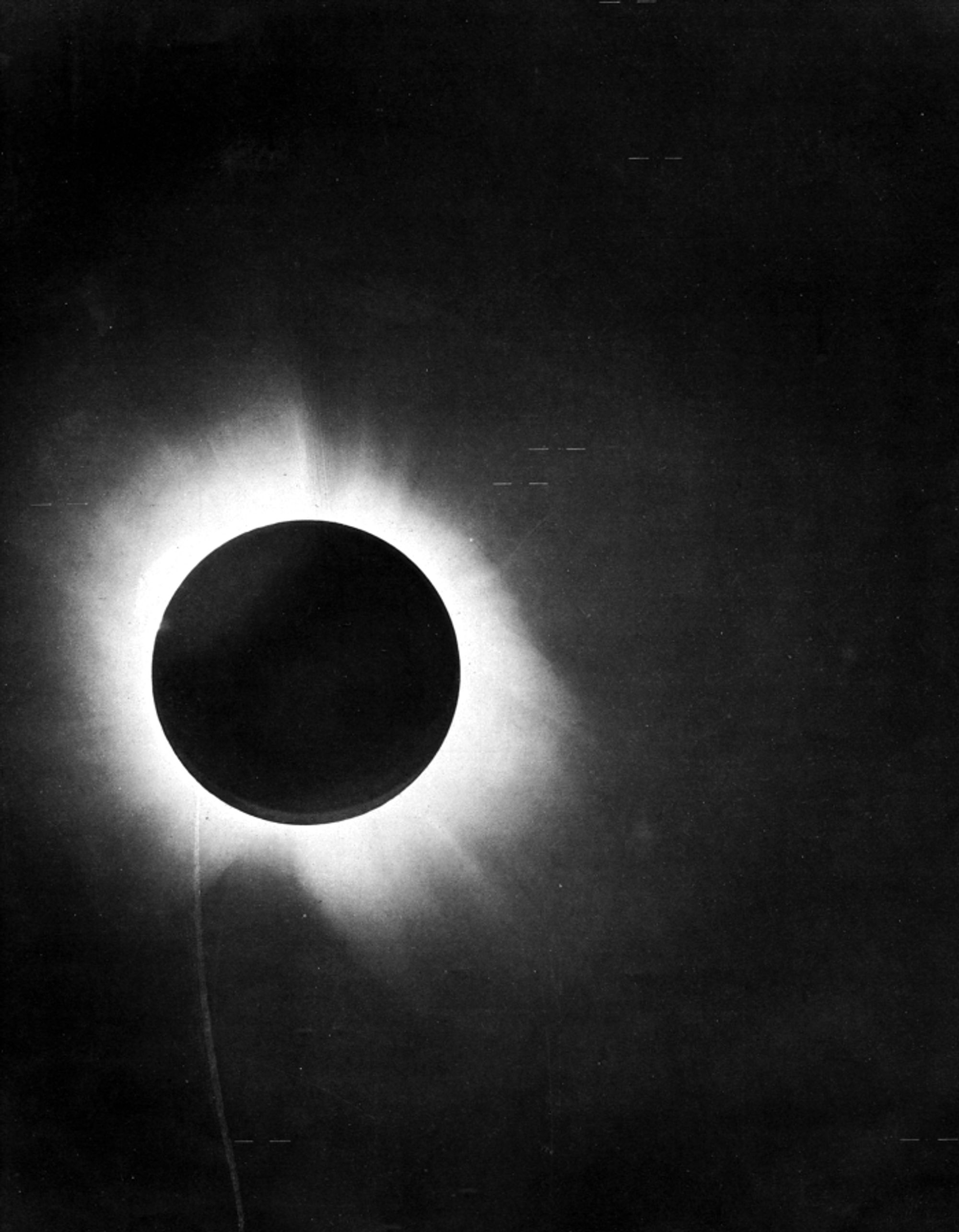

As if to challenge the ancient eclipse for pre-eminence, that of May 29th in the year 1919 is a worthy candidate. It was predicted long in advance, and the British launched an expedition, led by Arthur Eddington, to a West African island to photograph the field of stars right around the Sun during totality. Eddington had calculated how much the Sun’s gravity would bend the starlight, according to Einstein’s recently published theory of gravity (“general relativity”). Careful measurement confirmed the amount of bend predicted by Einstein’s theory. At the meeting of the Royal Society when this result was announced, it was described as the “greatest scientific achievement since Copernicus,” and the next day’s London Times was headlined “Newton’s Ideas Overthrown.”

Eddington himself, another fan of Omar Khayyam, adopted Khayyam’s classic quatrain form to describe the event at the post-conference party. It ended:

Five minutes, not a moment left to waste.

Five minutes, for the picture to be traced.

The stars are shining, and Coronal Light

Streams from the Orb of Darkness—oh, make haste!

Oh, leave the wise our measurements to collate,

One thing at least is certain, that light has weight.

One thing is certain, and the rest debate:

Light rays, when near the Sun, do not go straight!

May 30

On this day in 1971, NASA launched Mariner 9, the first spacecraft to reach and orbit Mars. Mars was the great hope for finding alien life in the solar system, and that life was the subject of many science-fiction novels. Even Tarzan (hero of the African jungle) got into the act, conquering Mars at one point. There was great excitement that year about the expected close-up photographs. The spacecraft arrived in August, and the first photos looked pretty much like the views I got through my homemade six-inch telescope. Blurry! Mars was in the grip of a planet-wide dust storm, and hardly any detail could be seen. A few weeks later, the dust subsided and we got some great photos: of a giant Martian volcano, and the first hint of long-dried-up Martian river valleys.

May 31

Sunrise 5:27 am EDT

Sunset 8:20 pm EDT ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast