Big Apple Sky Calendar: June 2022

In the 1990s, astronomy professor Joe Patterson wrote and illustrated a seasonal newsletter, in the style of an old-fashioned paper zine, of astronomical highlights visible from New York City. His affable style mixed wit and history with astronomy for a completely charming, largely undiscovered cult classic: Big Apple Astronomy. For Broadcast, Joe shares current monthly issues of Big Apple Sky Calendar, the guide to sky viewing that used to conclude the seasonal newsletter. Steal a few moments of reprieve from the city’s mayhem to take in these sights. As Oscar Wilde said, “we are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.”

—Janna Levin, editor-in-chief

June 1

Sunrise 5:27 am EDT

Sunset 8:21 pm EDT

June 7

First quarter Moon. High in the early evening sky, setting around midnight.

June 10

On this day in 1854, a young German mathematician gave a “job talk,” hoping to secure a faculty appointment at the university in Gottingen. His name was Georg Riemann, and he discussed what we now call “Riemannian geometry”—a system in which the normal laws of plane geometry fail. Fortunately for the future of mathematics, he got the job. Unfortunately, his life was short (he died at 39)…but his work inspired generations of mathematicians, including probably Lewis Carroll (aka the Oxford mathematician Georg Dodgson) whose famous works suggest settings in which all the familiar assumptions are wrong (“six impossible things before breakfast”). Albert Einstein always marveled at Riemann’s genius, and credited his discovery of Riemannian geometry as leading to his work on gravity (general relativity).

June 12

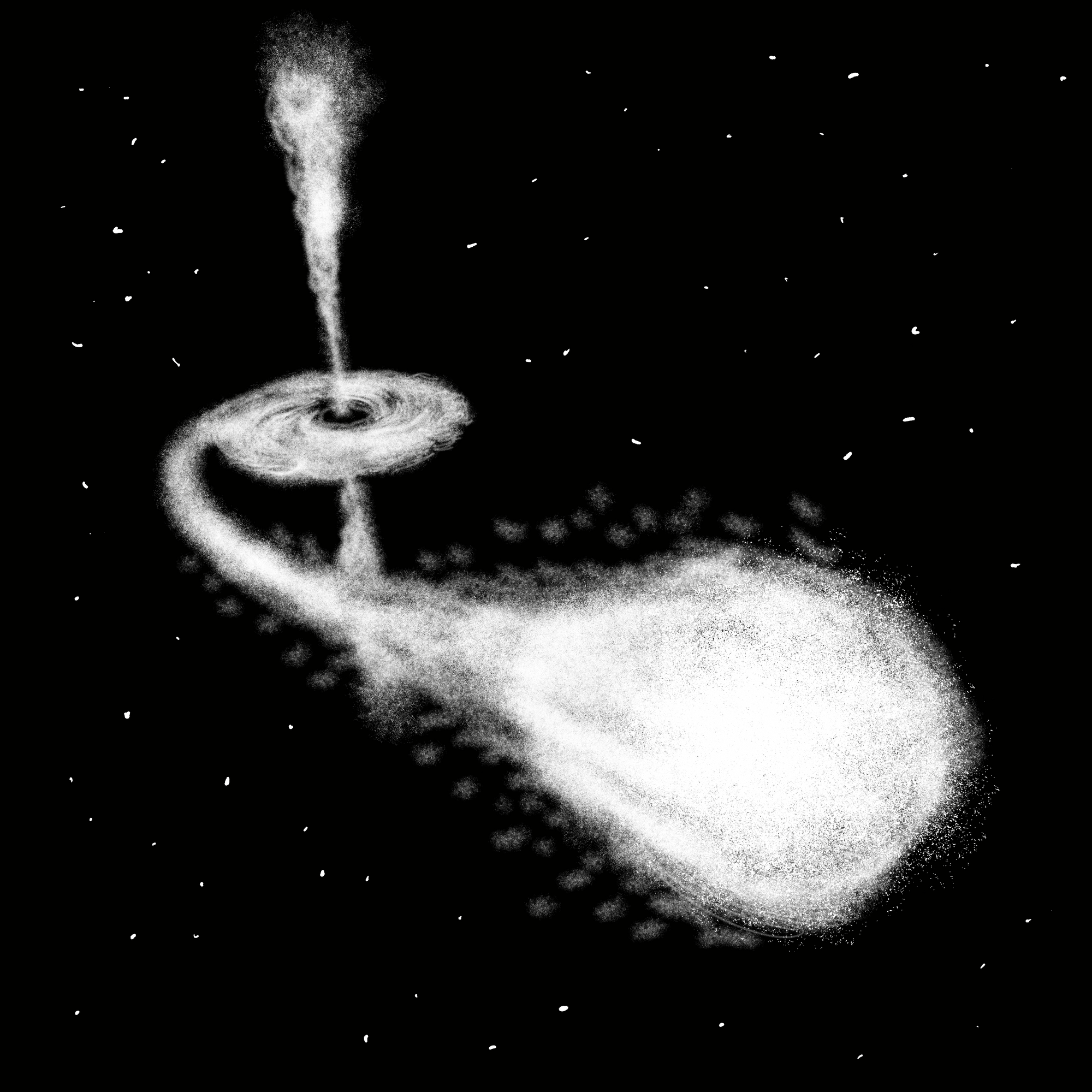

On this day in 1962 a rocket was launched with a detector sensitive to X-rays. Its team of scientists had previously detected X-rays from the Sun, so they figured, “why not the next brightest thing in the sky—the Moon?” During the 5-minute flight above the Earth’s atmosphere, they found X-rays, but not from the Moon. The X-rays came from a little patch of sky with nothing distinctive in it—not a planet, galaxy, bright star, or anything familiar. Later flights identified the source as a faint blue star with an odd spectrum. It was named Scorpius X-1, and was the subject of hundreds of papers speculating about its nature. It turned out to be a neutron star—a tiny, solid star made entirely of neutrons. The idea is that if another, normal star is orbiting very close to a neutron star, gas from the companion star will get pulled by the immense gravity, and come crashing down onto the neutron star’s surface, producing copious X-rays. Sco X-1 was the first of many thousand such stars now known in the Galaxy.

A few years later, a similar object was discovered, called “Cygnus X-1.” It contained not a neutron star but a black hole—the first one discovered. In those days, X-ray binary stars like Cygnus X-1 received swashbuckling names (I'm sure my black cat wasn't the only one named Cygnus). Nowadays, these stars get names like 3XMM J004232.1+411314. Not likely to inspire any beloved pet names.

June 13

Birthday of Thomas Young in 1773. Young is most famous for his wave theory of light—the first to explain interference phenomena. He made many discoveries in diverse fields: vision, mathematics, history, Egyptology, music, energy, and the theory of matter. And these were just his hobbies! His main job was as a physician—a doctor—and he went to some trouble to prevent his amazing scientific work from interfering with his medical practice. With good reason, he is frequently described as “the last man who knew everything.”

June 14

Full Moon. Of course, the full moon is always opposite the Sun. And since the June Sun rises very high in the noontime sky, it follows that the full moon is now as far south (and therefore low in our sky) as it ever gets. Watch it as it just grazes those trees in your southern sky around midnight. Independent of all that, the Moon is also today at “perigee”—as close to the Earth as it ever gets. Therefore its angular diameter is now as great as it ever gets…and writers of astronomy columns, desperate for drama, have recently decided to call this a Super Moon. But don’t be fooled. The eccentricity of the Moon’s orbit is only 0.09, which means that you really can’t tell full moons apart: Super, Mini, or Mean (unless you lay them side by side). For a real Super Moon, you have to go back about four billion years. The Moon has been slowly out-spiraling ever since, as it steals angular momentum from the Earth’s spin.

June 15

Sunrise 5:24 am EDT

Sunset 8:29 pm EDT

June 16

Mercury at greatest western elongation. Mercury can only be seen in morning or evening twilight, because it orbits so close to the Sun. A week either side of this date, you might glimpse it: quite low in the eastern sky, about 45 minutes before sunrise. But don’t bet the farm on it; sightings of Mercury are rare, and demand excellent viewing conditions. And during this week, they also require viewing around 4:30 am.

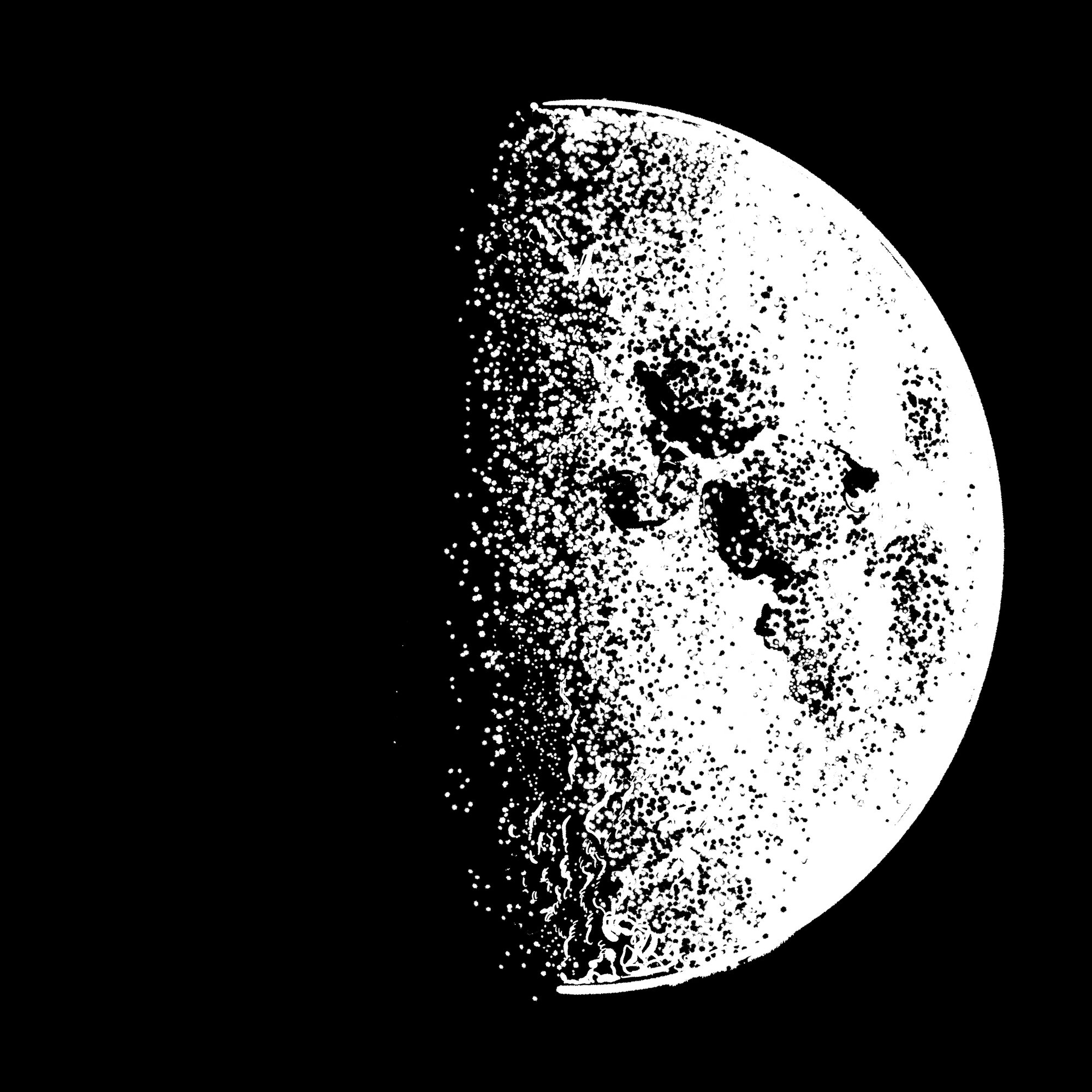

June 20

Last quarter Moon, rising around midnight. Excellent time to scan the Moon's craters with a telescope or binoculars. The Sun is just setting over the most heavily cratered region on the Moon—creating more contrast and therefore great viewing.

June 21

Summer solstice 7:51 am EDT. Or, for “hemispheric correctness,” the June solstice (since it’s the beginning of winter in the Southern Hemisphere). The noontime Sun is high in our sky, and at the North Pole it will stay in the sky continuously for three more months. At Fairbanks, Alaska, which is almost exactly on the Arctic Circle, the Sun “sets” at midnight, and “rises” a few minutes later—having just barely touched the northern horizon. So the day is essentially a 24-hour affair. Fairbanks has a golf tournament and a 6-mile road race (“Midnight Sun Run”) starting at midnight. At the South Pole, where the Sun disappeared on March 21, it’s now fully dark, and that darkness will only be relieved by a little tinge of twilight starting in mid-August. (The Sun won’t actually rise there until September 23.)

June 22

Bertolt Brecht said it best on a large curtain which opened the Inquisition Trial scene, near the end of his play Galileo:

June 22, 1633.

A momentous date for you and me.

Of all the days, that was the one,

An age of reason could have begun.

On this day Galileo was convicted of heresy by the Roman Inquisition, and sentenced to lifetime house arrest. Brecht’s play beautifully captures the subtleties and conflicts leading up to this moment, which virtually extinguished science in Italy and much of the Catholic world for hundreds of years {the offending book, Dialogue Concerning Two Great World-Systems, remained on the official Index of Prohibited Books until 1835). Even at the time and within the Catholic hierarchy, the controversy of the verdict was recognized. Three of the ten Inquisitors did not sign the Oath—possibly members of the Jesuit order, which supported Galileo and has always been known for scholarship (plus, more recently, basketball).

There is a story that Galileo, after guilt was pronounced and the proceedings finished, said quietly but audibly, “Eppur si muove” (“and yet it moves”), referring to the Earth. In his book The Crime of Galileo, the historian Giorgio di Santillana discusses the question, did he really say it? For a man just convicted by the Inquisition, it would have been a pretty snarky comment. Di Santillana eventually concludes: maybe… but if he did, the Inquisitors “would have done their best not to hear.”

June 28

New Moon 10:52 pm EDT. With the Moon now effectively out of the sky, it’s a perfect time to do some summer star-gazing. The brightest parts of the Milky Way Galaxy appear in our sky any dark night around 11 pm–3 am. Look south to see the central regions of the Milky Way, or overhead to see the Northern Milk Way (Cygnus the Swan, and its neighbor constellations). But moonlight and city lights (especially!) are your sworn enemies in this enterprise. If you don’t manage this in late June, around the new Moon in late July is just as good.

June 30

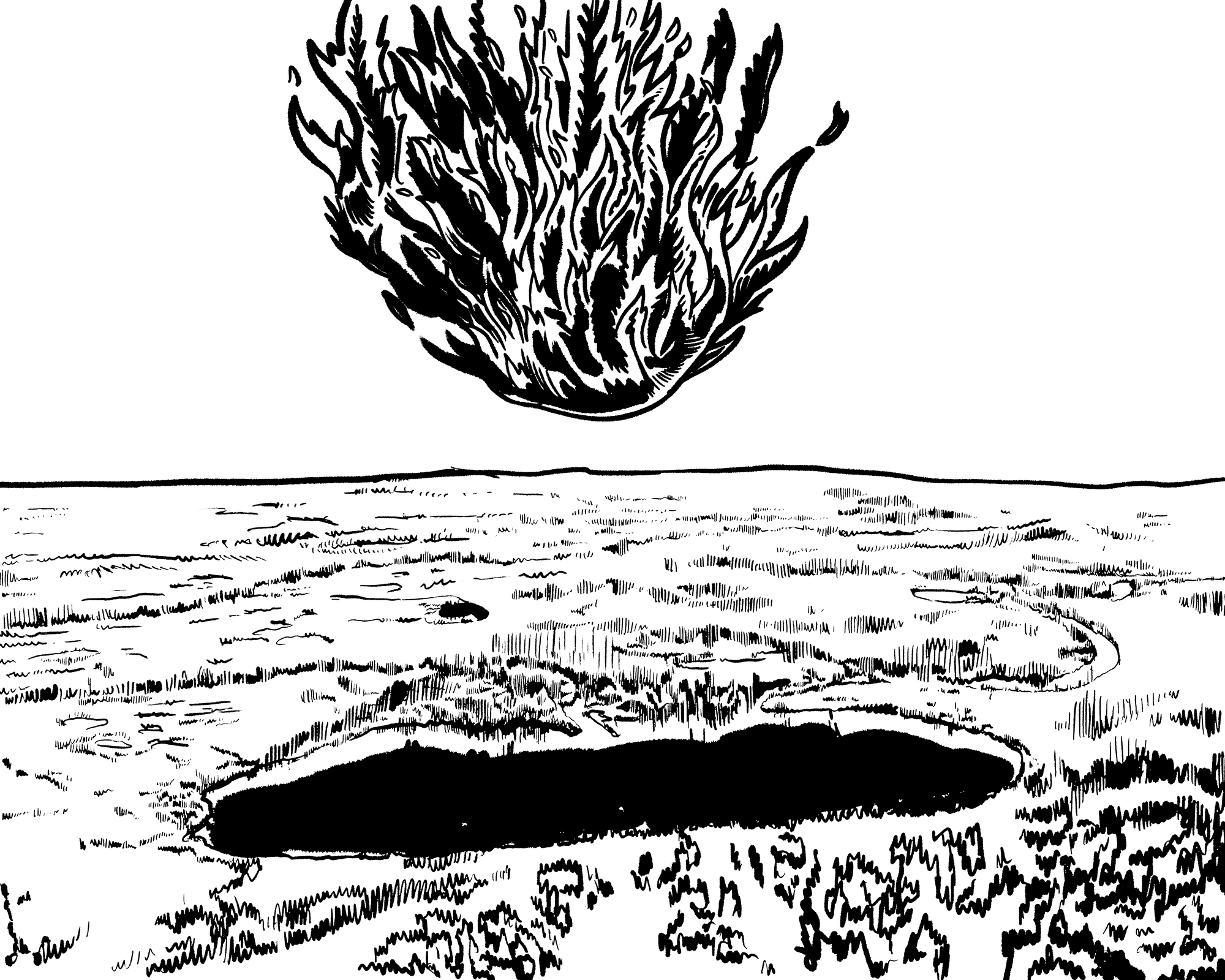

Tunguska! On this day in 1908, a gigantic explosion occurred in a remote region of Siberia. Years later, a Russian astronomer, leafing through a book in a library, found a newspaper clipping from 1908 which described the event (apparently someone had used it as a bookmark). It intrigued him, and he launched an expedition to the area, near the Tunguska River. He found a region of complete devastation. Over a radius of 20 miles, millions of trees had been knocked down in a radial pattern, and there were many skeletons of dead reindeer. This was obviously the remnant of the 1908 explosion. Interviews with local residents reported it looking like “a piece broken off the Sun.” We still don’t know exactly what caused this event, which struck with an energy many times greater than the Hiroshima bomb. Most astronomers think it was the impact of a small comet or asteroid, which broke up on encountering the Earth’s atmosphere (thus explaining the lack of a crater).

June 30

Sunrise 5:28 am EDT

Sunset 8:31 pm EDT ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast