Being There, with Luc Sante

Behind a hedge of hemlock on two wildly different spring days—one unusually warm, the other colder than necessary—Luc Sante sat on his porch to talk about his latest book, Maybe the People Would Be the Times. Sante, of course, is one of the greatest chroniclers of street-level urban life (Low Life, The Other Paris) and in his new essay collection, he turns his gaze on New York City as he lived it, along with long critical engagements with music and photography and film and art and tabloids and fotonovelas and books.

When Sante was an adolescent Belgian immigrant in New Jersey, he had the passionate desire to get to what he writes about as the Now, a place where everything is happening, life and culture and artmaking and things he didn’t yet understand. Everyone who has ever left their origin for the big city has a Now, and anyone who’s then departed knows that it doesn’t last, but if you’re lucky you get there and get drawn into the centrifugal force of the city’s wild-eyed creative geniuses and are there watching and making and listening, right in the center of it all. You’ve probably had a Now. But Sante’s Now was, let’s face it, better than most.

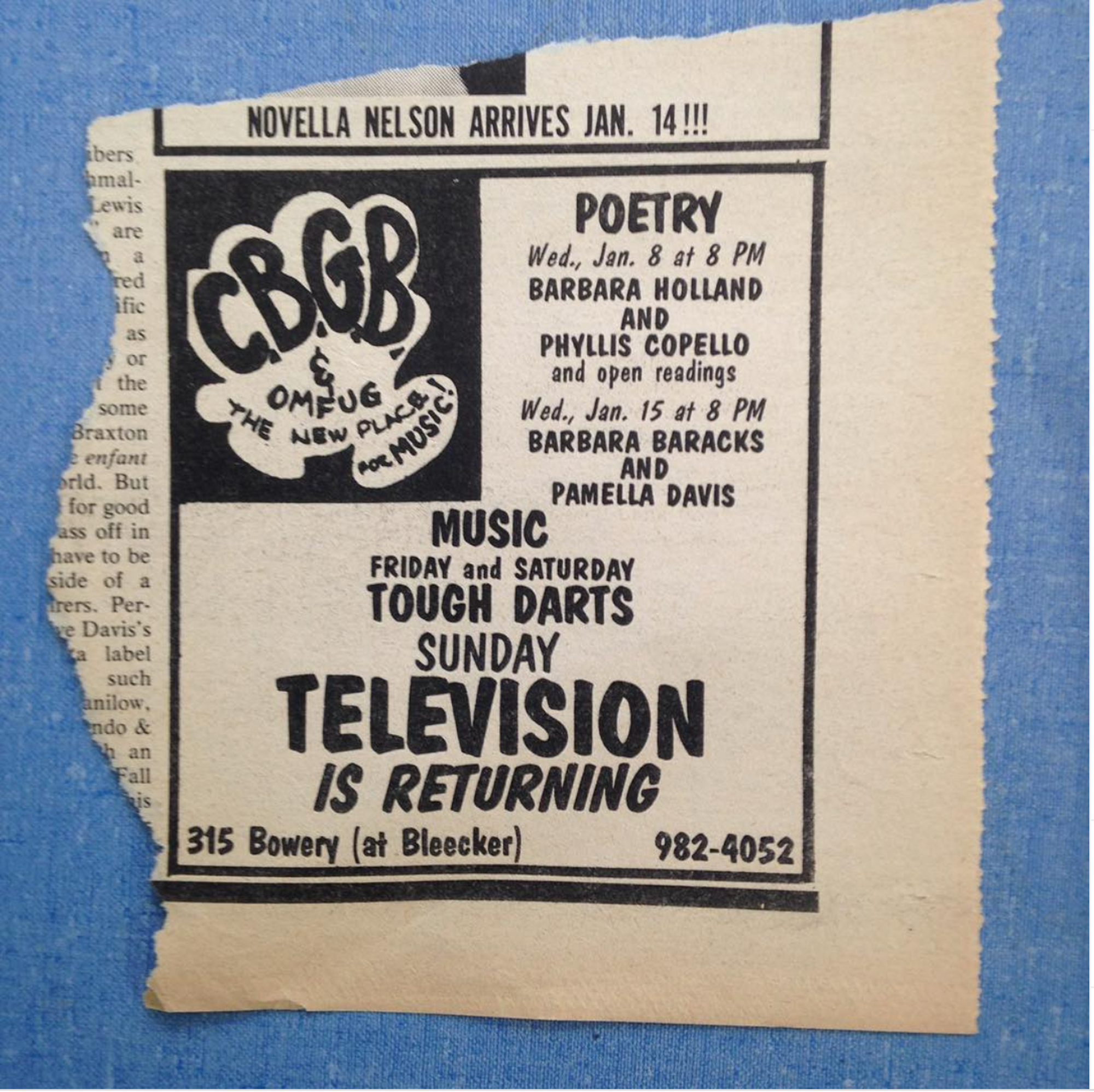

Moving to New York City in 1972, he saw Patti Smith’s earliest performances; frequented a new club called CBGB’s; passed through the St. Marks Poetry Project; bumped into Jean-Michel Basquiat. And so many clubs and galleries and cultural eddies that are long gone.

We’re lucky that Sante is the one who comes back with the stories, because he’s so much more than a witness. Sante has unending curiosity that makes him turn from one subject to something completely different, a commitment to bohemianism and an aversion to trends, a distrust of wealth, and a range of references that I’d call encyclopedic but I’m pretty sure an encyclopedia couldn’t hold them.

Some of the pieces in the book appeared in the New York Review of Books, others on the Paris Review blog and his own, in Bookforum, Artforum, Harper’s, Vice, elsewhere and unpublished, and one in the Beastie Boys book. For more than 20 years he’s taught creative writing and the history of photography at Bard College. Our conversation has been edited.

When did you get to New York City?

’72. I started commuting to high school in ’68. I did that for two and a half years until I got kicked out, and then a year and a half later I started Columbia. I lived in Manhattan til ’92 and I lived in the city until 2000. Right away, I thought that the only place I'd want to live is New York or Paris or maybe San Francisco, but New York and Paris were my poles. New York was this cauldron that was affecting world culture, but there was also a very local culture, and New York in the sixties was a really amazing place. Because it blended together high and low, and at the same time, it was the Big City and it was kind of a village. One of the great things about those days is that almost everybody was listed in the phone book. I mean, you could look up Andy Warhol, Igor Stravinsky, they were in the phone book. It gave you the sense that this is where everybody cool lived and, in those days, they would rub elbows, they'd see each other not just at gallery openings, but at the grocery store. It had a more communal feeling.

I lived for over 10 years in what was called the Poet's Building, which I write about in “Neighbors,” but I don't write about the poets. I write about the regular working class people in that building. But it also featured Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky, Arthur Russell, Richard Hell, who still lives there, and lots of lesser known Poetry Project people. The time when the Poetry Project was at its peak in terms of coolness, let's say, was in the early seventies. At that point, nobody had any expectations of ever making any money on their art, and that's where I came in. You lived in the Lower East Side because you want to live for cheap and make your art. It was taken for granted that you were going to work as a proofreader or in a bookstore or taking legal transcriptions or whatever, pretty much for the rest of your life. And that's okay because your rent was $98 a month.

We can look back now and see that was this self-driving furnace for creativity that seems singular. Do you think it could happen again? Or do you think that in this book you’re memorializing something that happens once in a generation?

It's very hard to say. I mean, I believe that to have a thriving arts community, the thing you need is cheap housing above all. And it's not just that housing is expensive, but also you can no longer, if you're young and broke, you won’t necessarily be able to live in the same neighborhood as your friends. And you need that physical proximity. You need to see everybody having breakfast together at the Ukrainian coffee shop, you know? It may happen again. It may not happen in New York. It might happen in Albany. It might happen in some weird place. You know, we'll know. Like in 10 years we'll suddenly wake up one day and find out that Wake Forest North Carolina has been the center of everything for a while, and we just didn't know about it.

I’m sure you’re asked this all the time, but do you miss New York City?

I profoundly miss the New York City of pre-1983 or so. I miss that so much. Before COVID I was there almost every week, and most of my friends are still in the city, so I have a social life down there that even though I've been here for two decades has no equivalent up here. Down there, in the eighties, it's true of the seventies too, especially on the Lower East Side, I could not walk a block without running into people. That doesn't happen anymore. There's so many more young people, succeeding waves of young people. Anyway, the city now, it’s going to be interesting to see what shakes out of all this. But it's just too battering to me to go to a neighborhood and not find anything except corporate nonsense. I used to have every neighborhood in Manhattan blocked out: Let's go see a movie. Oh, it's playing on East 86th street. Well, we'll be a little early, but I know like three bookstores we can hang out in. Those bookstores are all gone. Or place, just places to just hang, you know? Bookstores, record stores, junk shops, those places where you just go in and browse. Now the only way you can hang is by consuming something. I can go to museums, but it’s not the same. You know, I went to high school three blocks from the Metropolitan Museum. In those days it wasn't even a suggested donation. You just walked in and it was empty most of the time. You could have a 19th century French painting to yourself for hours. There was nobody there. It was fantastic.

I’ve been in Paris for a total of about 48 hours but I managed to get to the Louvre and had 19th century French painting to myself there. Everyone was off standing in line for the Mona Lisa.

I feel very lucky that I went to Louvre a whole lot of times before the tourist plague. When I went to the Louvre with my mother in 1963, I was eight and it was my first experience at a museum. What blew my mind was the room with the big early 19th century paintings like The Raft of the Medusa. They scared the shit out of me. But it was like, there's a word for this, when you have the profound existential reaction to art, where it flattens you, but elevates you at the same time. It's terrifying. But great. My other favorite Louvre story is when I was a student there in ’74, I went in one day and it felt like I was the only person in the entire museum who was not a Red Guard, hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of Red Guards and their blue uniforms and caps and with the Little Red Book in their pockets.

Sounds like a surreal film! How did you end up going from New York to Paris? What were you studying?

Well, first of all, I was very stupid. I was going to do a junior year abroad. But then I fell in love and so I switched to the summer program instead. And at the summer program, I met the great love of my life Number One, who was the subject of “ESP” in the book [the first essay], that's where we met. We spent the summer canoodling in various sections of Paris. I was there in a program on post-structuralism. I was a student of Sylvère Lotringer, his first year teaching in America, the guy who founded Semiotext(e) and the third subject of I Love Dick by Chris Kraus. I studied The Vampirism of the Senses, these hifalutin courses. I remember I was really, really envious because I met a guy who—we were living at the Columbia House in Paris, they have this amazing 18th century house, they don't have people living in it anymore—I met an American student who was studying at the Sorbonne and he was taking Roland Barthes’ class and he said, every week it's a different word or maybe two words, and he just will go off on that word. And that's what became the book Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes.

Wow. So what, what was wrong with this picture? It sounds amazing.

You know, the courses I was taking, I found less than engaging because frankly there was a lot of gobbledygook.

The piece “12 Sides,” short stories inspired by 12 records, is fiction. It’s an interesting way of writing about music without writing about music.

There are a few things in the book that had very specific prompts. In this case, it was for a show catalog for a show at Duke that was devoted to vinyl. What do you want to write about vinyl? I have hundreds and hundreds of 45s, many of which I bought in the late ‘70s when I was working at The Strand, from one of the last Fourth Avenue bookstores—they had huge stacks of 45s for like a dime apiece or a nickel apiece. I'd have to like take a chance that they were going to be playable. But so many of them had names written on the labels. That was the inspiration.

In a series essays on photography, you move through a set of ideas that explore and elevate vernacular photography.

I came into the photography field kind of backwards. I started becoming interested in photography as a result of buying old photographs and especially old photo postcards back when Astor Place was a 24-7 flea market and incredible things would show up and you’d pay a dollar for them. Seeing this photography that I think is art, but nobody intended it to be art, that really picked up my interest. And then as a result of my second book, Evidence, I started getting offers to write about photography and it became a whole second career. To me still the most interesting thing is vernacular photography.

Do you have the problem of the collector, drowning in your own enthusiasm?

Well, I don't collect anymore. I put a stop to it. Um, every once in a while, I'll, you know, I'll go on eBay and see something incredible and have to buy it. This happens. With the photo postcards, I bought my first one, I think in 1980 and collected for 30 years. I knew by a few years into it I was going to write a book. And then I made up my mind beforehand, the minute I write the book I stopped buying and that's it.

What do you think the role of criticism is?

I've always had an uneasy relationship with criticism. In the eighties when I started writing professionally, mostly what I wrote were reviews because the only other avenue open to young writers was personality profiles, and I was way too shy to do that. And also, I don't like celebrity. So I wrote reviews, I wrote a lot of reviews. Many of them ephemeral, best forgotten. I was a movie critic for a couple years, I wrote record reviews. But when I was young, I sometimes wrote mean reviews. Then I realized that I was deeply uncomfortable doing that unless there was a moral point. The only reason for writing a mean review was if something was being sold under false pretenses or if it was some big, popular shebang, that kind of thing. But writing a mean review of a first novel is really useless and cruel. I still review every once in a while. Mostly it’s review-essays. Partly because I got my college education at the New York Review of Books, and that's where I learned I can write one of those things, at the age of 26 working for Barbara Epstein. That started my whole career right there. It's all about considering a book, movie, even record, as a gateway into a whole world. Or then reviewing the work of the auteur in whatever form, as a totality, all these things that take it from being a review to being criticism. And since I don't engage in any kind of theory, it's practical criticism.

What is practical criticism?

Well, okay, I'm talking through my hat and I think there's probably a definition of practical criticism which is not what I'm saying, but what I mean is, something that addresses real world concerns without an academic scrim on it at all. People used to tell me, aha, but you say you don't use theory, but that just means you're using theory. You know, forget about it.

Do you mean that you include the biography and culture moment of these figures?

You have all these waves in every kind of literary and art criticism both, either the autobiography of the auteur is the key to the work, or the work stands entirely apart from autobiography, et cetera. And you know, these are useful optics for specific laboratory situations, but in the real world, there's interplay between those things. That's where I stand, is right in the middle.

Can you tell me more about working with Barbara Epstein?

Absolutely. I’d known I wanted to be a writer since I was at least 10. But as soon as I got near the New York literary world, I didn’t want any part of it. I mean, I was strongly attracted at first to St. Mark's Poetry Project; they were hippies, et cetera. But the New York literary world seemed stiff, hidebound, reactionary. I hated it. I hated pretty much all the writing that came out of it. I was devoted to one author—and that was Thomas Pynchon. He was like my patron saint for a really long time. I lined up at Scribner's bookstore at nine o'clock in the morning to buy the first copy of Gravity's Rainbow. But I could only afford the paperback, which is only worth a fraction of what the hardcover is. So anyway, by the time 1980 rolled around, I didn't read the New York Review. I did not read the New Yorker. But then working with Barbara was like a complete change because I loved Barbara. I just loved her as much as I've ever loved anyone in my life. She was a role model. She was nobody's fool. She got my jokes, I got her jokes. She was part of this establishment but also like a teenage guttersnipe making fun of it at the same time. She won me over 100%. I started reading the New York Review—working in the mail room, I would kind of glance at it, but I was interested in my own shit. But when I started working for Barbara, I started really reading it. And that's when I decided, Hey, I could write one of these too. My first piece was published in December ’81 and that was the official beginning of my career.

I still didn't really dig the literary crowd unless I could view it through Barbara's viewpoint. And I still do that. Her way of reading and also the people who were her friends. I didn't like all her friends, but many of her people were the really good people. And I realized that I had these anti-adult, anti-establishment prejudices that kept me from seeing what was there, because after all, they're writers too. They’re bad writers just as there are a zillion bad writers today, but nevertheless, there will be people with whom I share a common goal and a similar heart. Barbara allowed me to see that. And also impressed me with the hard work of it. I have her voice in my head at all times when I'm writing: this is too many words, we've already said that in the previous sentence, that is a dead phrase, overused, all these things. I hear Barbara say it and I revise accordingly. I mean, really, she made my writing.

What a great thing to have a good editor.

More than an editor, she was my teacher, my mother. I owe her everything.

In “The Now” you write, “I had a million questions I couldn’t even frame as questions, which resolved into a single glowing orb of curiosity.” That’s about New York City, which answers some of those questions. But has the curiosity stuck with you?

In a different guise, yes. It's the way I write my books. It's the way I write my pieces. I go into a subject like Paris or something, not really knowing what I'm looking for, but kind of knowing. I'm magnetized. You know the old thing: if you're a hammer, everything looks like a nail. When you have the single glowing orb of curiosity, you start finding what you're looking for behind every bush. It did not start as a writing method, but it ended up that way.

Subscribe to Broadcast