Baby-Making on Mars

This essay appears in print in our latest issue—alongside pieces by Emily Raboteau, Marcus J. Moore, and Catherine Lacey; poems by Eileen Myles, Ariana Reines, and Brandon Kilbourne; and drawings by Daniel Johnston.

The year was 1982, and Jeffrey Alberts needed to get into the Soviet Union. He couldn’t fly there from America. President Reagan had escalated the Cold War; direct flights between the two countries had been halted the year before. Alberts was instructed to fly to London by a man named Richard Keefe.

“I met Dick for the very first time, face to face, according to his instructions, in front of Barclays Bank in Heathrow Airport,” Alberts recently recounted. “He would be the guy wearing a Russian hat.”

And Alberts? He was the tall guy with wild hair and a goatee. If you are picturing Alberts as a spy, maybe a hero from a le Carré novel, I’ll tell you that he is a hero, but of a different stripe. A professor in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences at Indiana University, he had—at his fellow scientist Keefe’s behest—become an integral part of a high-stakes NASA mission. To complete his objective, Alberts needed to get into the Soviet Union and send 10 pregnant white Wistar rats into low Earth orbit on board the Soviet spacecraft Kosmos 1514.

Against formidable odds—the Cold War, the Iron Curtain, and even rogue monkeys—Alberts and his colleagues forged a rare scientific collaboration. Together, from the United States and the former Soviet Union, they carried out research that is now fundamental to our understanding of whether human life can be sustained beyond our planet Earth. They were the first scientists to study pregnant mammals in space.

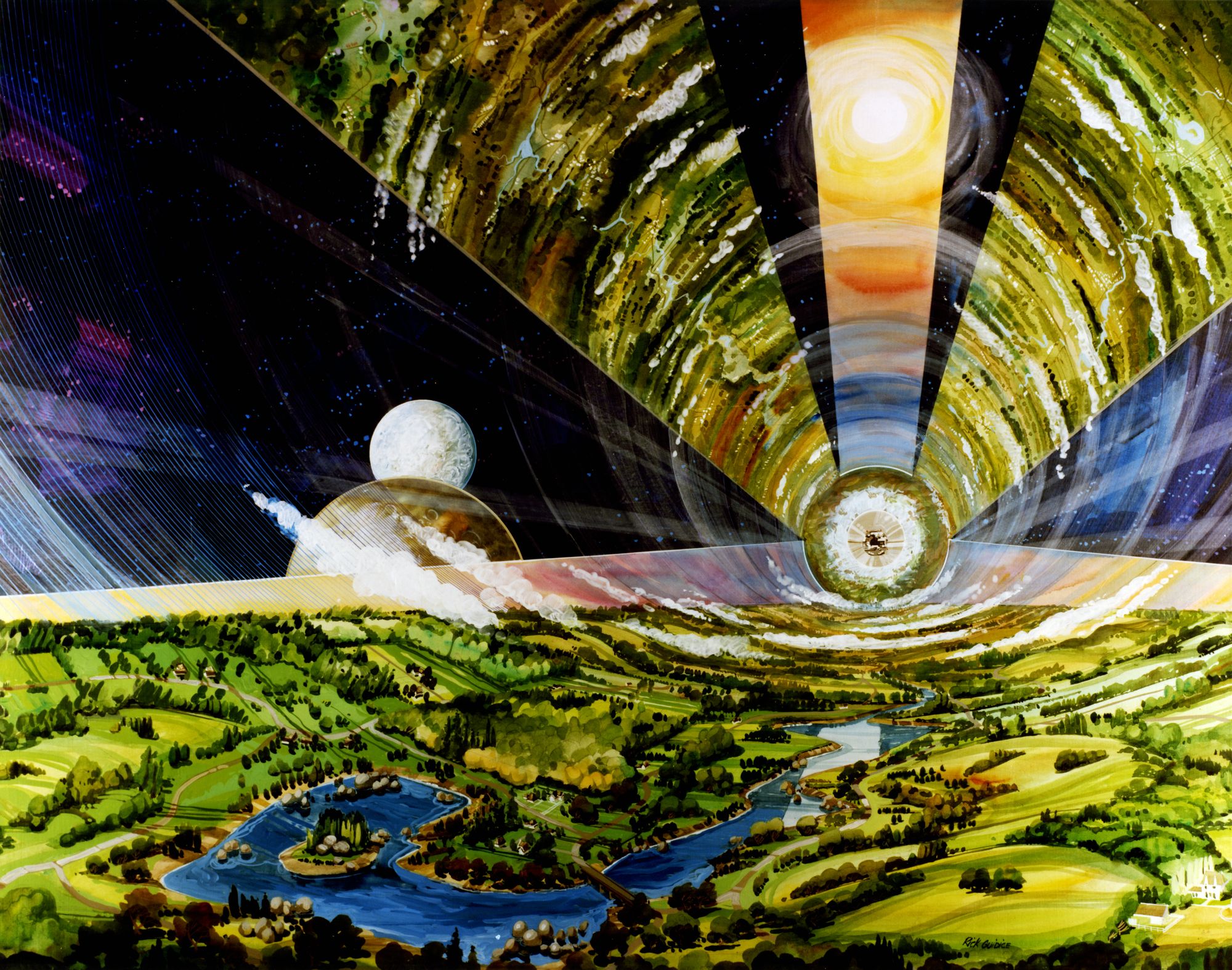

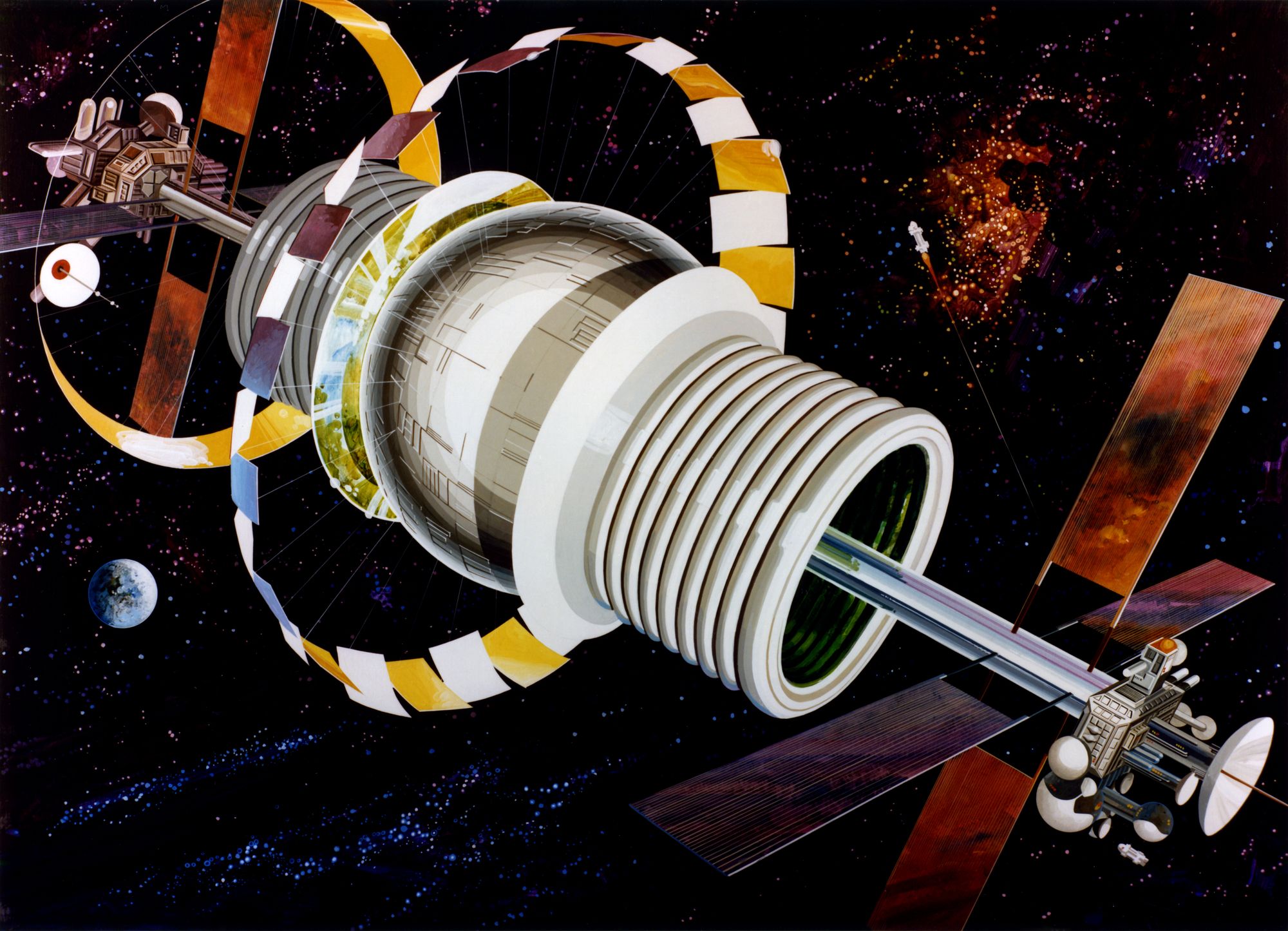

A rendering of the interior of an O'Neill Cylinder space colony, 1970s.

Courtesy of NASA/Rick GuidiceThese days, conversations about humans moving off Earth tend to revolve around a pair of billionaires—Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos. On January 16, 2025, Musk's SpaceX conducted the seventh test flight of Starship—a skyscraper of a rocket, the largest ever built, designed to carry humans to Mars. SpaceX plans to launch thousands of Starship rockets in the coming decades. On the very same day, 15 hours earlier, Bezos’s Blue Origin launched New Glenn—a smaller, yet still massive spacecraft designed to carry both people and cargo into orbit. While Musk envisions a future on Mars, Bezos imagines humans living in giant space stations orbiting Earth.

Their escapades and rivalry tend to dominate the airwaves, but the tech moguls are not the only ones preparing to take us off-planet. NASA is working to build a lunar outpost (while also proposing, as Musk and Bezos both do, that we mine our Moon for resources). NASA’s Artemis Base Camp—named after Apollo’s twin sister and goddess of the Moon—will feature a network of landing pads, roads, sheds, and acorn-shaped habitats, all 3-D-printed by robots using Moon dust. Construction hasn’t begun yet, but blueprints are in progress with viability tests underway. The Artemis Program was launched in 2019, during the first Trump presidency, and both Musk and Bezos hold contracts to transport astronauts to the lunar surface.

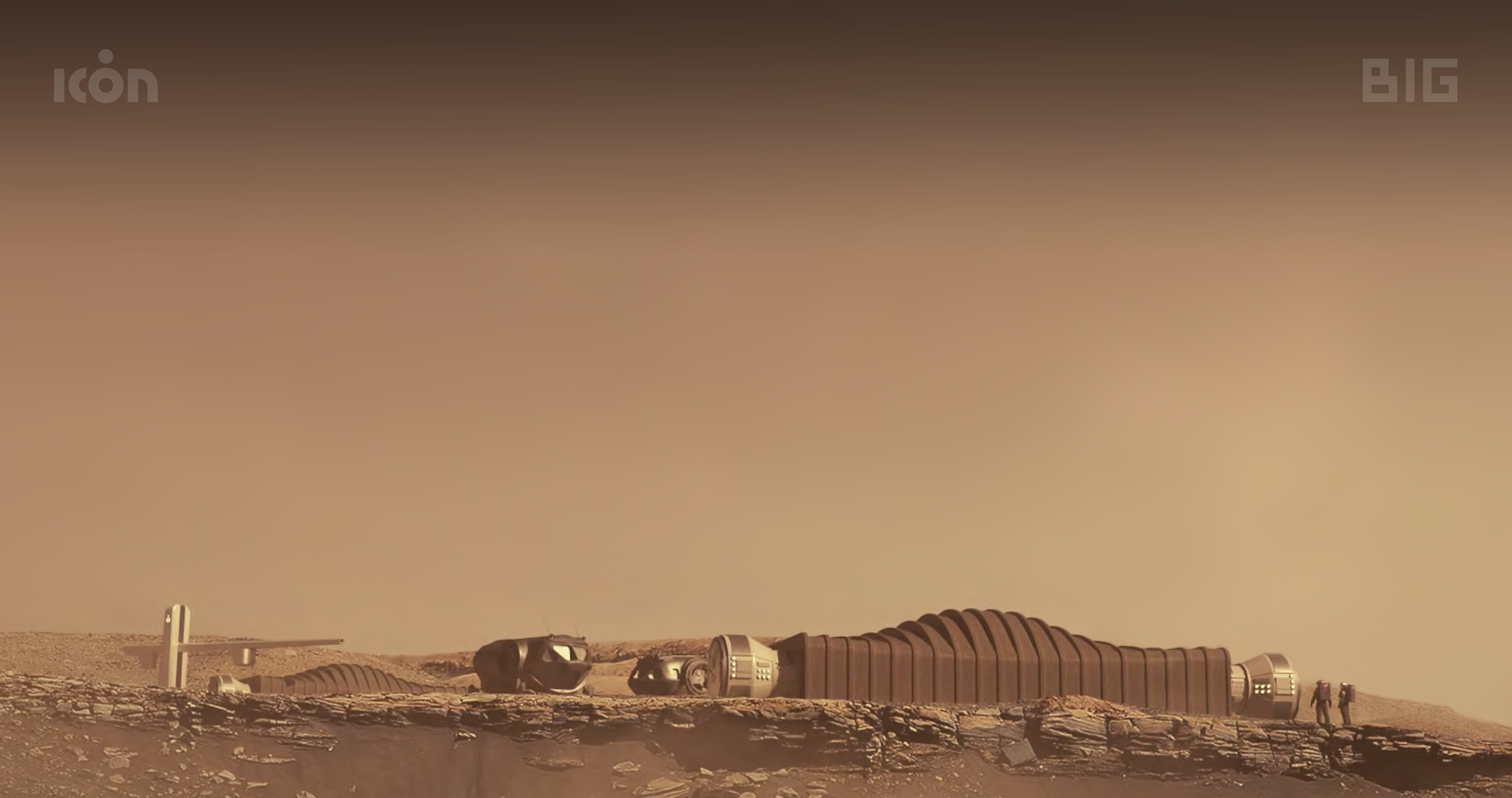

Rendering of a lunar habitat, designed by Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), in collaboration with 3-D-printing startup ICON and design firm SEArch+.

Courtesy of ICON and Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG)Rendering of ICON's Olympus system, which will 3-D print landing pads, roadways, and habitats on the lunar surface.

Courtesy of ICONWith Trump back in the White House, there are signs that the United States—while not abandoning plans for the Moon—is shifting its priority toward sending humans to Mars. Trump could change course at any moment, but NASA has been preparing for this goal, too. On July 6 of 2024, a crew of four volunteers concluded a 378-day stay in “Mars Dune Alpha,” an isolated 1,700-square-foot 3-D-printed habitat designed to help us prepare for life on the Red Planet. Two more such simulations are in the works.

The United States is not alone in its space ambitions, and political tensions here on Earth are playing out above us. China and Russia are collaborating on a lunar base, which they plan to complete by the mid-2030s. China is also preparing to send crewed missions to Mars, signaling its intent to challenge the United States for dominion in deep space.

Moving to Mars may strike you as fanciful—for who would choose to live in the discomfort of outer space? But consider this: In 2013, when the Dutch entrepreneur Bas Lansdorp offered four volunteers one-way tickets to Mars—albeit through his ill-fated and widely criticized Mars One project—202,586 people from more than 140 countries applied.

Rendering of Mars Dune Alpha, designed by Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), in collaboration with 3-D printing startup ICON and design firm SEArch+.

Courtesy of ICON and Bjark Ingels Group (BIG)Humanity has entered a new era of space exploration. This time, we don't just want to visit, we want to stay. From Musk and Bezos to former NASA administrator Michael Griffin and the late astrophysicist Stephen Hawking, advocates for moving off-planet increasingly frame the need to migrate as imperative to our survival, key to withstanding existential threats and building long-term resilience. But if getting to space will be a feat of engineering, staying there will be a feat of biology.

We’ll need to conceive and raise children away from Earth. Mothers and their young—not towering rockets—will bear the most weight of our space dreams. It’s through them that humanity will transform into a multi-planetary species. And for all the excitement about venturing into space, we know astonishingly little about how life there will affect pregnancies or child development—and, by extension, the future evolution of our species.

Whether space can actually save us remains far from certain.

*

As an evolutionary biologist, I find the prospect of humans moving off-Earth both thrilling and terrifying. Few behaviors have shaped our evolution as profoundly as migration, and not since the first group of adventurous humans—Homo erectus—left Africa nearly two million years ago has any human made such a bold move. Homo sapiens eventually followed, migrating out of Africa. We spread through Europe and Asia, interbreeding with other human groups—which increased our genetic diversity—and adapted to varied environments. This is how modern sapiens became who we are today. When we leave our planet—say for Mars—we will enter a radically new world, where adapting to less gravity will rank amongst our greatest challenges. Our biological and behavioral flexibility will be pushed to its limits, forcing a new phase of evolution with unpredictable consequences.

Homo sapiens have extraordinary flexibility when we are young, and evolution occurs through changes in development—starting in the embryo, long before birth. The environment of space will trigger a cascade of shifts—from our cells all the way to our culture—leading to new developmental outcomes. Some individuals might develop denser bones, others enhanced balance or behaviors better suited to surviving the planet-wide dust storms of Mars, where technological mastery may become as crucial as physiological adaptation. Traits that improve survival and reproduction on the Red Planet will spread through the population by means of natural selection, as those better adapted to the new circumstances will be more likely to survive and bear children. Their children will, in turn, be shaped by similar evolutionary forces.

But there's more to this story: an expectant mother, though increasingly treated by U.S. laws as a vessel for her fetus, isn’t merely that. Humans are part of a group of eutherian—colloquially called placental—mammals. Among our fellow animals in this group are rats, bats, pets like cats and dogs, farm animals, elephants, shrews, whales, and even armadillos. What unites us is how our mothers nourish us in the womb: through the placenta, which forms where the embryo attaches to the uterus. The placenta is a shared organ, composed of tissues from both mother and fetus. It produces hormones that affect both. Through the placenta, the two work as one unit, with intertwined cardiovascular, pulmonary, immune, and metabolic functions. Pregnancy transforms a mother’s physiology in ways that support her survival and that of her unborn child. In strict scientific terms, neither the fetus nor the mother is a traditional biological "individual"—they are a fused entity.

The daily rhythms of a mother’s life shape the senses of her fetus. Her speech, laughter, moods, heartbeat, the foods she eats, and even her breathing can be felt inside the womb. When she walks—an act that requires gravity—her fetus feels the changing pressure and hears the rhythm of her footsteps. It experiences shifts in spatial orientation and balance—vestibular shifts. These experiences mold the sensorimotor capabilities of the fetus. Environmental factors that alter the mother’s behavior or physiology—like, for example, dwelling in outer space—will inevitably alter her fetus.

After birth, mammalian mothers remain of paramount importance. A baby depends on its mother for survival and well-being, and other caregivers play crucial roles, too. Early care—whether from the mother or other adults—regulates the expression of hundreds of genes in a child through epigenetic modifications. When caregivers are under extreme stress, they may struggle to meet the child's needs, leading to neglect that can cause lifelong biological and behavioral challenges—and not just through epigenetic changes. The child may develop psychiatric disorders, have reduced brain volume and sensorimotor impairments, and, in extreme cases, suffer DNA damage. The unforgiving environment of space could amplify these harmful effects in a growing population, diminishing overall survival and reproductive fitness.

“Development is the artist; natural selection, the curator,” the biologist Scott Gilbert reminds us. After many rounds of selection—which we too often reduce to the cliché “survival of the fittest”—the brains, bodies, and behaviors of those who prevail will be transformed. And they may become something else entirely: Homo martians, if Mars is to be their home.

But before we get to any of these daunting unknowns, there are concrete questions with more immediate urgency. For example: Can mammalian pregnancies, including ours, even progress in outer space? Can fetuses develop without Earth's gravity? And if so, how might the unique conditions of space alter our basic sensorimotor abilities? If we plan to move away from Earth, we need answers. We need to know if we can adapt to vastly different worlds.

It was these very questions of life—and life beyond Earth—that took Jeffrey Alberts, 43 years ago, to Heathrow Airport to scan the crowds for a furry Russian hat by Barclays Bank. The experiments that grew from this meeting provide some of the only answers we have.

*

Alberts’s encounter with space biology—the study of how living beings adapt to outer space—was serendipitous. In the late 1970s, during his early years as a professor at Indiana, Alberts recalls being "totally indifferent to all of this stuff." But a master's student in his department—a Trekkie—had developed a passion for space science. Alberts encouraged her to follow her heart, and she followed it to Texas—attending what he thought was a “crazy-sounding” conference on how altered gravity affects animals.

One night, not long after his student attended the conference, Alberts was working late in his office when the phone unexpectedly rang. It was Richard Keefe, a neuroanatomist from Case Western Reserve University’s School of Medicine. Keefe had been working with NASA for several years and had learned of Alberts’s expertise in rodent sensory development from his student at the Texas conference.

The Russians were planning to send pregnant rats into space, Keefe explained. A select group of American scientists would work with NASA and be granted access to these animals. Would Alberts be interested in studying how rats develop in microgravity? "I just said yes," Alberts recalled, when I reached him via Zoom at his office in Bloomington. "It sounded like something I could do, and it was certainly exotic."

Over the next two years, Alberts and Keefe spoke regularly by phone, and under Keefe’s guidance, Alberts developed prototypes for experimental equipment in line with NASA’s specifications. He rigged cages to monitor the pregnant rats—the dams—after their trip to space and designed a series of tests to study the sensorimotor functioning of their pups, who would be born back on Earth after their prenatal stint in orbit. He devised thin mercury-filled tubes to wrap around the bellies of the pink, hairless rat pups who, at birth, are the size of a human pinkie finger. The tubes would stretch and compress with each breath the pups took, tracing their respiration. He had tests to tell how well the pups could roll over from back to belly—"righting" themselves—on a solid surface, a measure of their tactile and vestibular abilities. A similar test in water would eliminate the feedback of touch, isolating their sense of balance and spatial orientation. There were devices that emitted puffs of odor while monitoring the pups’ sniff rates. He had hearing tests, too, and optokinetic drums—rotating instruments often used to test vision in humans.

The sensory systems of birds and mammals—ours included—become functional in a fixed order: touch comes first, followed by the vestibular system (our motion sensor that detects acceleration, head movement, and spatial orientation to help us maintain posture and balance), then the chemical senses (smell and taste), hearing, and finally sight. In most species, the tactile, vestibular, and chemical senses come online in utero. Human fetuses can hear in the womb, but vision develops largely after birth. In rats, both hearing and sight develop postnatally. Despite these differences in timing across species, the study of space-exposed pregnant rats and their progeny would offer insights into how human sensory development might be altered beyond Earth.

In 1981, Alberts took his wares to NASA Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California—where he caught the space bug. “It turns out I like big things," he recalled, with a hearty laugh, “...and NASA is full of gigantic things.” Walking down the sidewalks, Alberts saw pressure tanks so large that the bolts holding them down were wider than his arms—the arms of a six-foot-one man—could reach around. There was the world’s largest wind tunnel, where rockets were tested to ensure they didn’t break apart while propelling through the atmosphere on their way to outer space. He saw centrifuges designed to test astronauts’ tolerance to accelerations greater than those experienced in Earth’s gravity—a kind of salad spinner for humans.

Alberts was dazzled. The equipment, the launches, the very dream of going to space—they were all gigantic.

The Wind Tunnel at NASA's Ames Research Center, 1979.

Courtesy of NASA/Ames Research Center/Melliar Ritchie/Don Richey*

We take gravity for granted. After all, we've never known life without it. Gravity is a fundamental force of nature. It sculpts galaxies. It warps space and time. It holds the universe together. Gravity also gives Earth her spherical shape. It is needed for rain to fall, for soil to drain, for heat to spread, for air and water to separate. Gravity gives weight to all things—animate and inanimate—and keeps us all from floating off into space.

Throughout the roughly four billion years of biological evolution on our planet, gravity—its intensity and direction—has remained constant. It's the only environmental parameter to have done so. Earth’s temperature, atmosphere, and sea level, for instance, have all fluctuated dramatically. Plant sensitivity to the Earth's gravitational pull—gravitropism—is what makes their roots grow downward and stems grow upward. When the first sea creatures crawled onto land some 390 million years ago, their bodies and brains had to adapt to a new gravitational load. Similarly, adaptation to Earth's 1-G environment has influenced our body shape, muscle tone, locomotion, and even brain structure.

While each planet, moon, and asteroid has its own gravitational pull, the intensities vary. The Moon's gravity is roughly 17 percent of ours, making movements feel much lighter for astronauts who walk on its surface. Mars, currently considered the most viable option for human habitation, has approximately 38 percent of Earth's surface gravity. Europa, a moon of Jupiter and another top contender for human settlement, has only around 13 percent of our gravity.

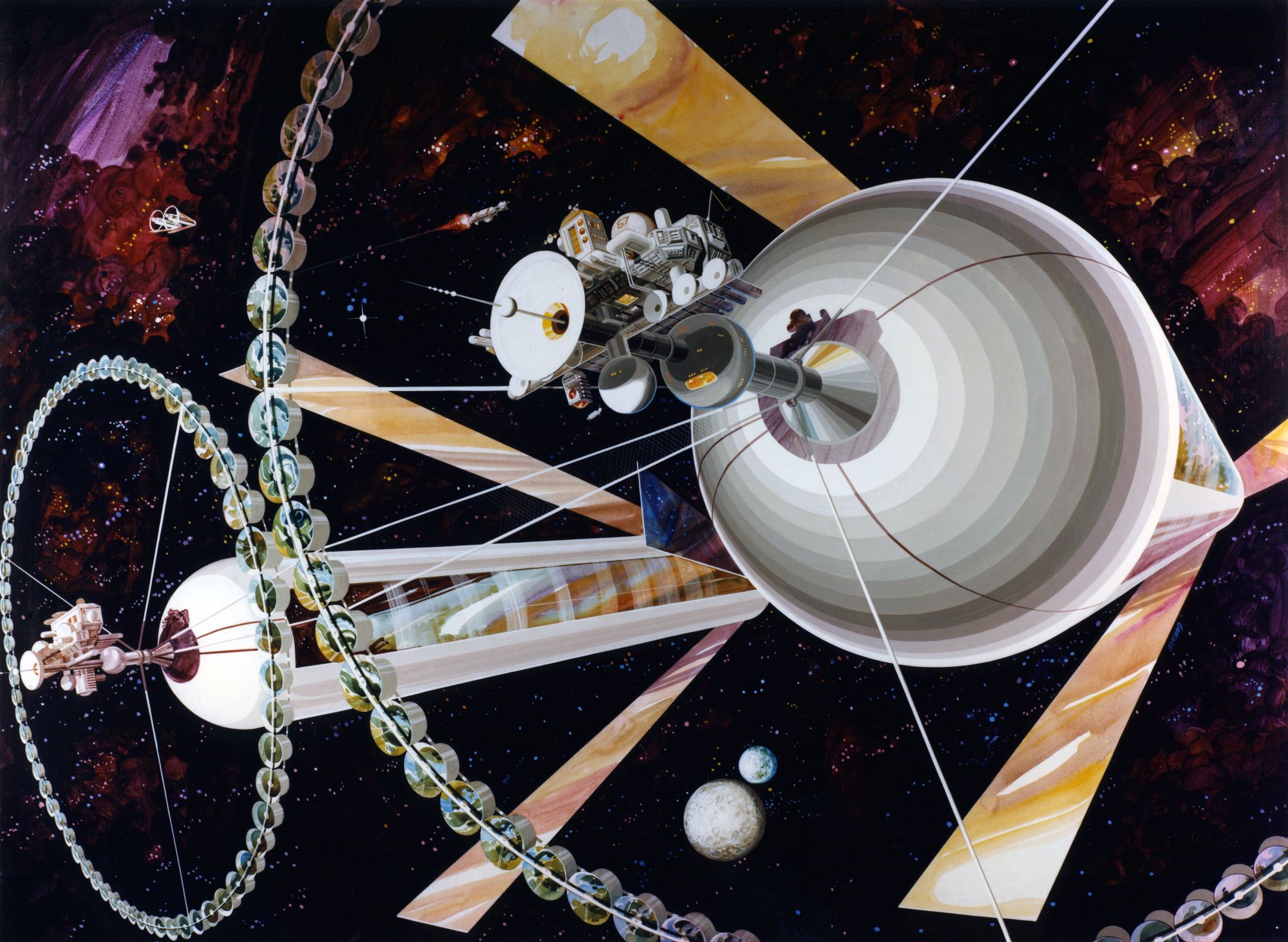

Exterior view of a pair of O'Neill cylinders, 1970s.

Courtesy of NASA/Rick GuidiceJeff Bezos hopes to sidestep the problem of lower gravitational forces by building floating colonies with artificial gravity. He draws inspiration from Princeton physicist Gerard O’Neill's 1976 book The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space, in which O’Neill proposed that Earth-like gravity could be generated by the centrifugal force of counter-rotating cylinders, each about 20 miles long and four miles in diameter: a machine whose inner surface would roughly equal the size of the city of Los Angeles, upon which millions of people could dwell.

O’Neill cylinders have become a popular motif in science fiction. At the end of the movie Interstellar, for example, Matthew McConaughey’s character finds himself in a hospital inside a cylinder orbiting Saturn. As he looks out the window of his ground-floor room, we see his incredulous gaze shift upward—from a baseball field to concave farms to inverted houses overhead.

Seductive though this idea may be, it has garnered less popular support than settling Mars—largely due to the immense engineering and financial challenges involved in building and maintaining such structures. Many view Mars as offering a more “natural,” if still daunting, second home for humanity.

While today’s discussions—at least in the United States—center on where humans might settle in space, the Russians, as far back as the 1960s, were asking a more fundamental question: if Earth’s life forms can survive and reproduce over multiple generations without Earth’s gravity. From the earliest days of space biology, they were studying the reproduction and development of both plants and animals in microgravity. They were visionaries, says Alberts.

*

When Alberts and Keefe boarded a Japan Airlines flight in London, bound for Moscow, their destination was the Institute of Biomedical Problems—the Soviet space biology institute. There, together with a team from NASA, they would negotiate the protocols for sending pregnant mammals into space for the very first time. Back then, it was science—not colonization—that motivated their efforts.

For Alberts, the U.S.S.R. itself became a part of space biology’s allure. “That brought its own total intrigue, crazy mystery, and romance about it,” he recalls. “It was behind the Iron Curtain, and it was dark and gray—literally. There was no food, and it was very harsh conditions, and they were doing this exotic space experiment at the same time. It was an alternative universe.”

Scientific collaboration aside, political tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union were high. The NASA scientists, some of whom had been coming to Moscow for years, learned to gauge just how high the tensions were based on where they were housed. Of his first trip in 1982, Alberts said, “The hotel they put us in was far away from everything and very, very isolated.” A van was sent to escort the group to the Institute of Biomedical Problems, about a 20-minute drive from Red Square.

Expecting the grandeur of NASA, Alberts was surprised by what he saw. “The Institute was just these drab Soviet buildings,” he told me, reminiscent of housing developments across the Eastern Bloc. Inside, the common toilet everyone used had long since lost its seat, and in lieu of toilet paper, there were newspaper squares, cut up and stacked in a little pile.

“And yet they were doing the most extravagant scientific experiments,” Alberts said. “They were hosting nine nations on these flights, and it was all being run out of this very, very, very plain place. It was always a reminder of how determined they were.”

The satellite that would carry the pregnant rats into space was designated Kosmos 1514. It was the seventh in a series of biosatellites launched by the Russians as part of their Bion Program, established in 1966. Biosatellites, which typically fly without a human crew, are designed to carry plants and animals to space and back, in order to study how spaceflight affects their biology and behavior. This one, Kosmos 1514, was a roughly two-foot-wide spherical metal capsule with a large observation window in the center, a flat cylindrical service module on one end, and a conical propulsion module on the other.

When it began, the Bion program was solely a Soviet endeavor. But by the mid-1970s, Bion had evolved into a truly international collaboration, with scientists from countries as geographically and politically diverse as the United States, France, the Czech Republic, Lithuania, Romania, Bulgaria, China, and the former German Democratic Republic placing their biological payloads on the Soviet-funded and -operated Kosmos satellites. Collectively, the Bion missions offered—and continue to offer—the single largest source of data on how living beings function in microgravity.

Image of Kosmos 1514, launched in 1983.

Courtesy of Wikimedia CommonsMicrogravity, the Bion scientists had discovered by 1982, affects fully developed and developing beings differently, with varied outcomes based on both the organism and its developmental stage. In general, the plants fared better than animals. In the absence of gravity, it turned out, plants can rely on other environmental cues—such as light—to orient and guide their growth. With the right kind of grow-chamber to mitigate the indirect effects of microgravity—for instance, the lack of natural convection, and therefore limited oxygen flow—the plants developed much as they did on Earth, but produced fewer viable seeds in space.

In contrast, fungi—neither plant nor animal, and belonging to their own kingdom—fared poorly in microgravity. They returned oddly shaped, with atrophied stems and enlarged heads. Among the animals, frogs and fish hatched successfully, but upon returning to Earth, they were found to swim atypically—an indication of altered vestibular function. Flour beetles and fruit flies also reproduced in space, but the young flies were hyperactive and died early.

An astronaut holding a pregnant frog during a Spacelab-J experiment studying how microgravity affects amphibian development, 1992.

Courtesy of NASAIn 1979, 60 quail eggs were sent into low Earth orbit on a Kosmos satellite for 18 and a half days. They were damaged on reentry into Earth's atmosphere by an incubator malfunction, but dissections revealed that embryonic development had proceeded in microgravity. Experiments on subsequent flights confirmed this, but the chicks that hatched in space developed severe abnormalities. Emily Morey-Holton, a scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center, reported that when released from the palm of the cosmonaut, "the bird first flapped its wings for orientation and began to spin like a ballerina, then kicked its legs, causing it to tumble." It struggled to fly and could barely perch long enough to peck at its food.

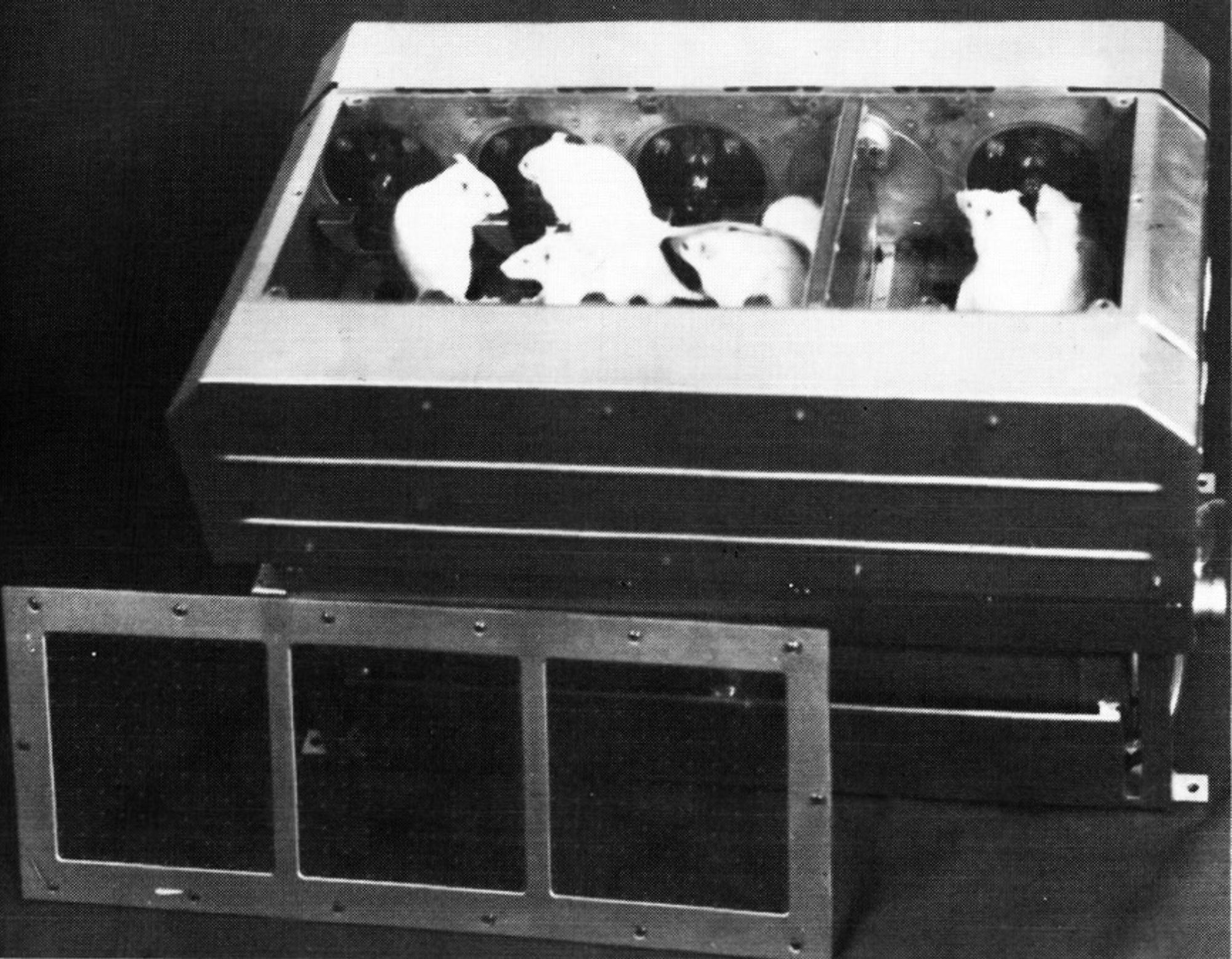

On that same Kosmos flight in 1979, the Russians made their first attempt to study mammalian reproduction by trying to mate rats while in orbit. Sadly, the rats did not mate, and the reasons remain unclear. Kosmos 1514, the mission Alberts was recruited to join, was a direct follow-up to this experiment. Instead of mating rats in space, the scientists planned to send already-pregnant dams who were roughly 60 percent through their pregnancies.

Rat BIOS with separator, as in Kosmos 1129.

Courtesy of NASA*

Kosmos 1514 was set to launch in December 1983. Now that the project had been green-lit, the scientist who’d brought Alberts to NASA, Richard Keefe, was no longer involved. Alberts was to work with Luba Serova, a Russian space biologist in charge of the Soviet side of their study. In earlier Kosmos missions, the Soviets had handled all the core parts of the operation: They recovered the animals, performed the dissections, and then passed the specimens to the Americans during a ceremonial “sharing of the tissue” meeting. But Alberts needed to study live rats, so the protocol had to be changed. “I was the first American to work shoulder to shoulder with Soviet scientists with living specimens,” Alberts explained. It was a big deal.

Alberts still speaks of Serova with great affection. “She's a total hero,” he told me. “She held these two sides together through all the political turmoil and extraordinary circumstances.” Serova was sharp and energetic, her hair a striking shade of orange-red—a color Alberts often noticed on the streets of Moscow, and understood more as the result of limited dye options than as a particular fashion. "She tended to sound like she was shouting when she would speak," he recalled, "barking commands in Russian." She worked brutally hard, often pushing herself to the point of total exhaustion. He sensed her home life was difficult. She lived with her mother and husband, and at the end of a long day of lab work (and a long commute home), Serova would do the housework. At times, he would see her eating scraps of food straight off a cast-iron pan that she had brought to work. Times were tough in the U.S.S.R.

Their collaboration got off to a good start. Alberts shipped 21 large crates of equipment from Bloomington to Moscow in preparation for the launch of Kosmos 1514. But then in September, just three months before the launch date, the Soviet military mistook a South Korean airliner for an American spy plane and shot it down over the Sea of Japan off of Siberia. All 269 people aboard died. Reagan cut off relations with the Soviet Union.

Federal projects between the two countries were to be shut down, putting Alberts’s years of work at risk. But an analysis of ongoing partnerships, conducted by the State Department, determined that this life science collaboration between the two countries wasn’t just rare; it was one of a kind. In a bureaucratic sleight of hand, federal authorities reclassified the experiment from “international cooperation” to an “interagency agreement,” thus bypassing the President’s decree.

*

Kosmos 1514 launched into low Earth orbit on December 14, 1983, from the Plesetsk Cosmodrome, 500 miles north of Moscow. On board were ten pregnant white Wistar rats, each at day 13 of their 22-day gestation cycle—and two adult male rhesus monkeys, named Abrek and Bion. They were there to help scientists understand why astronauts in space often experienced a headward shift of body fluids. The monkeys were implanted with sensors to monitor blood flow in their carotid arteries—the vessels in the neck that supply blood to the eyes and brain.

Abkhazia postage stamp illustrating Abrek and Bion on Kosmos 1514, 1983.

Alberts traveled to Moscow for the launch, but couldn’t visit the Plesetsk Kosmodrome to witness it. By Soviet decree, no American was allowed to see their space-vessels' launch—not even on a monitor. Meanwhile, a presidential order from Reagan had barred federal employees from flying in or out of the Soviet Union. So while Alberts had managed to reach Moscow by plane, his NASA colleagues had to take a train from Helsinki. “They came in sick as dogs,” Alberts recounted, “they’d caught a bug on the train.”

Kosmos 1514 was scheduled to remain in space for seven days. But one of the monkeys got out of his restraints and started dismantling the satellite from the inside. So the satellite was brought down early, after just four and a half days. It landed in a far-flung province of what is now the country of Kazakhstan.

The Soviet scientists, accompanied by the Soviet Space Force, set out to retrieve the animals. Since the Americans were to have no contact with the satellite, Alberts stayed in Moscow (years would pass before he finally saw a Kosmos biosatellite—on display at the Museum of Cosmonautics—its paint scorched, still carrying the sharp scent of reentry into Earth’s atmosphere). Alberts’s Soviet colleagues, in Kazakhstan, spent days crossing uneven terrain in a crawler-transporter, a massive tank-like vehicle designed to carry rockets. Their fur coats and hats offered little relief from the brutal cold. When they finally found the satellite, they threw up a semicircular quonset hut around it, installed picnic tables inside, and got to work beneath the flapping canvas. The picnic tables would double as dissection stations once the animals were retrieved.

Scientifically speaking, the mission’s shortened length was a blow. “Four and a half days is something like 20 percent of gestation, which is not great,” said Alberts, “but it’s way better than nothing.” Alberts had negotiated with the Russians to bring five of the 10 pregnant rats back to Moscow alive. The dams needed to be kept under strictly controlled conditions for the sake of the experiment, so Alberts hashed out every detail: how they would be transported, what they would be fed, and when. Unfortunately for him, his dear Soviet collaborator, Luba Serova, had other ideas.

“She was a scientist,” he recalled, “but a Russian woman in the richest sense of the word; who had decided—she was full of intuitions—that one of the females was feeling needy after the landing. So that rat was taken out of its cage and made the trip back to Moscow nestled in the cleavage of Luba’s breasts.”

This breach of protocol was, at the time, upsetting to Alberts. But all five females returned alive. Alberts was able to conduct his experiment, which aimed to answer two questions. The first was whether a mammalian pregnancy—at least in its latter stages—could withstand the challenge of microgravity. The second, if the fetuses survived, was to determine what had happened to their sensorimotor development.

Soviet Union postage stamp depicting the Soviet-Polish space flight, 1978.

Soviet Union postage stamp commemorating Cosmonauts' Day with Sputniks and Earth, 1963.

The first question was answered on Christmas Eve—before Alberts had even begun his testing. Late that night, he received a call in his hotel room. It was Serova, with good news: four of the five dams had given birth by natural delivery to live pups—the first mammals to have spent part of their gestation in the absence of Earth’s gravity.

When the scientists compared the flight dams with ground controls—pregnant rats at the same stage of pregnancy, housed and fed under identical conditions on Earth—they found that the rats’ duration of labor, number of pups born, pup weights, and even maternal care remained remarkably consistent.

The mother-fetus system, it would appear, was highly adaptable—capable of adjusting to an environment unlike any previously encountered on Earth. And with the birth of the Kosmos 1514 space pups, the idea of humans living beyond Earth moved out of the realm of science fiction.

*

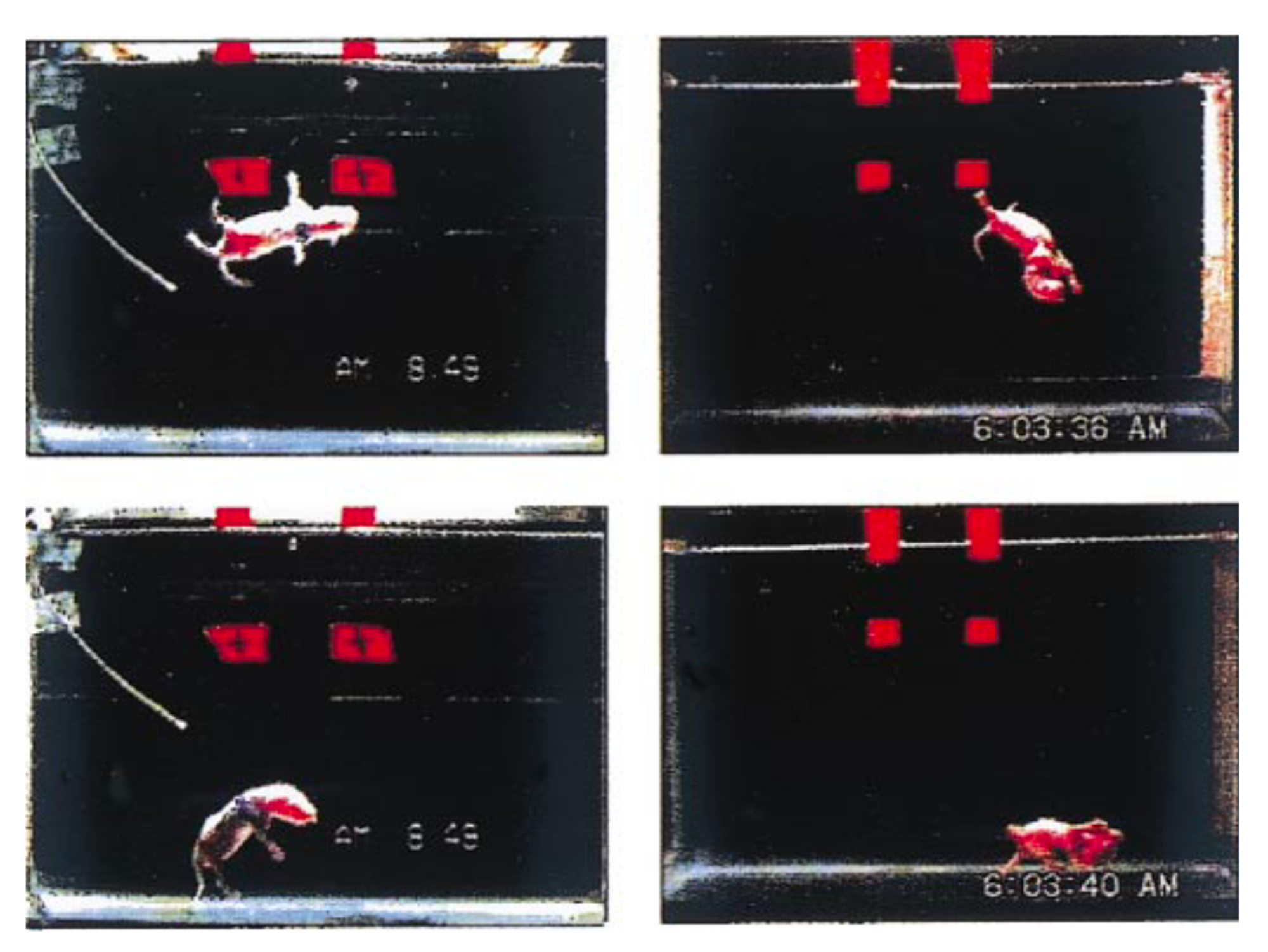

Years later, in the 1990s, Alberts and a NASA scientist named April Ronca conducted two follow-up experiments aboard NASA shuttles, which confirmed the findings from Kosmos 1514. In these missions, the rats spent the final 40 and 50 percent of their pregnancies in orbit. A key improvement here was the use of continuous video monitoring—24 hours a day, both in space and on Earth—which allowed the scientists to detect a subtle but significant difference during labor: The space dams, when they gave birth on Earth, experienced twice as many contractions as the ground controls.

Subsequent anatomical studies, conducted by colleagues of Alberts and Ronca in Canada, revealed that the muscles of the rats’ abdominal walls had been altered by their time in microgravity. Among the muscles that had weakened was the transversus abdominis—a deep core muscle that wraps around the spine and trunk like a corset. In both rats and humans, the transversus abdominis works with the diaphragm and the muscles of the pelvic floor to forcefully expel things from the body—be it feces, vomit, air during coughing and sneezing, or even a baby.

To understand why this muscle in particular had deconditioned, Alberts and Ronca turned to footage from the spaceflight. What they found was striking: The flight dams were rolling in their cages—roughly 700 percent more than their Earth-bound peers. Freed from gravity, they explored every surface—floor, walls, ceiling. They were small, furry astronauts in zero-G. When rolling, rats—and humans—engage our external oblique muscles, surface muscles on the sides of the abdomen. While those muscles are put to good use in space, muscles like the transversus abdominis—used to maintain and adjust body position in Earth’s gravity—are required less, and weaken. “Use it or lose it,” as the saying goes.

A deeper investigation revealed more clues. The flight dams had lower levels of connexin 43—a protein found in the smooth muscle layer of the uterus, in both rats and humans. The protein connects cells, one to another, conducting the contraction wave throughout the uterine tissue during labor. Reduced connexin 43, along with weak core muscles, would lead to weaker uterine contractions, requiring the mother's body to produce more contractions to move the fetus through the uterus and into the birth canal.

Pregnancy might survive outer space. Labor, on the other hand, could become significantly harder.

But back in the 1980s, Alberts did not know this yet—he was in Moscow, working with Serova to answer his second question by testing the pups’ sensorimotor responses on the day of their birth—“P0,” or postnatal day 0, in scientific parlance.

The sequence of sensory development in humans and rats may be the same, but the timings differ. Humans begin to hear in the third trimester, while our vision becomes functional shortly after birth. Rats, by contrast, are born blind and deaf and remain so for the first two weeks of postnatal life. At P0, they rely on their sense of touch, balance, taste, and smell—all of which develop before birth. In Moscow, Alberts’s tests showed that the other senses were largely intact, but their vestibular sense was clearly impaired (as was confirmed, a decade later, by more targeted testing after the two NASA flights).

To assess their vestibular function, Alberts held the pups on their backs in a warm bath—a position rat pups don’t particularly like—and then released them. Pups are naturally buoyant and tend not to sink like stones, giving them plenty of time to turn over and right themselves before reaching the bottom of the bath. When released by Alberts, in the absence of a surface to push against, the pups had to rely entirely on their sense of spatial orientation, posture, and balance—all functions of the vestibular system. Whereas 90 percent of the Earth-bound controls fully righted themselves, only 60 percent of the space pups managed to do so. The deficit persisted for five days, or until P5, after which the pups—still within the window of developmental plasticity—had adjusted to Earth’s gravity.

Video stills of P3 rat pups in a “water-immersion" test of vestibular development, showcasing the effects of prenatal spaceflight in neonatal rats.

Courtesy of Jeffrey AlbertsAfter their second NASA flight, Alberts and Ronca tested the fetuses just three hours after landing. Using heart rate as a proxy for cognitive engagement—a method also used in studies of humans—they found that the space-exposed fetuses showed strong sustained drops in heart rate—a sign of attention and learning—when rolled, while the Earth-bound controls barely responded. In this one respect, the space fetuses showed enhanced vestibular function.

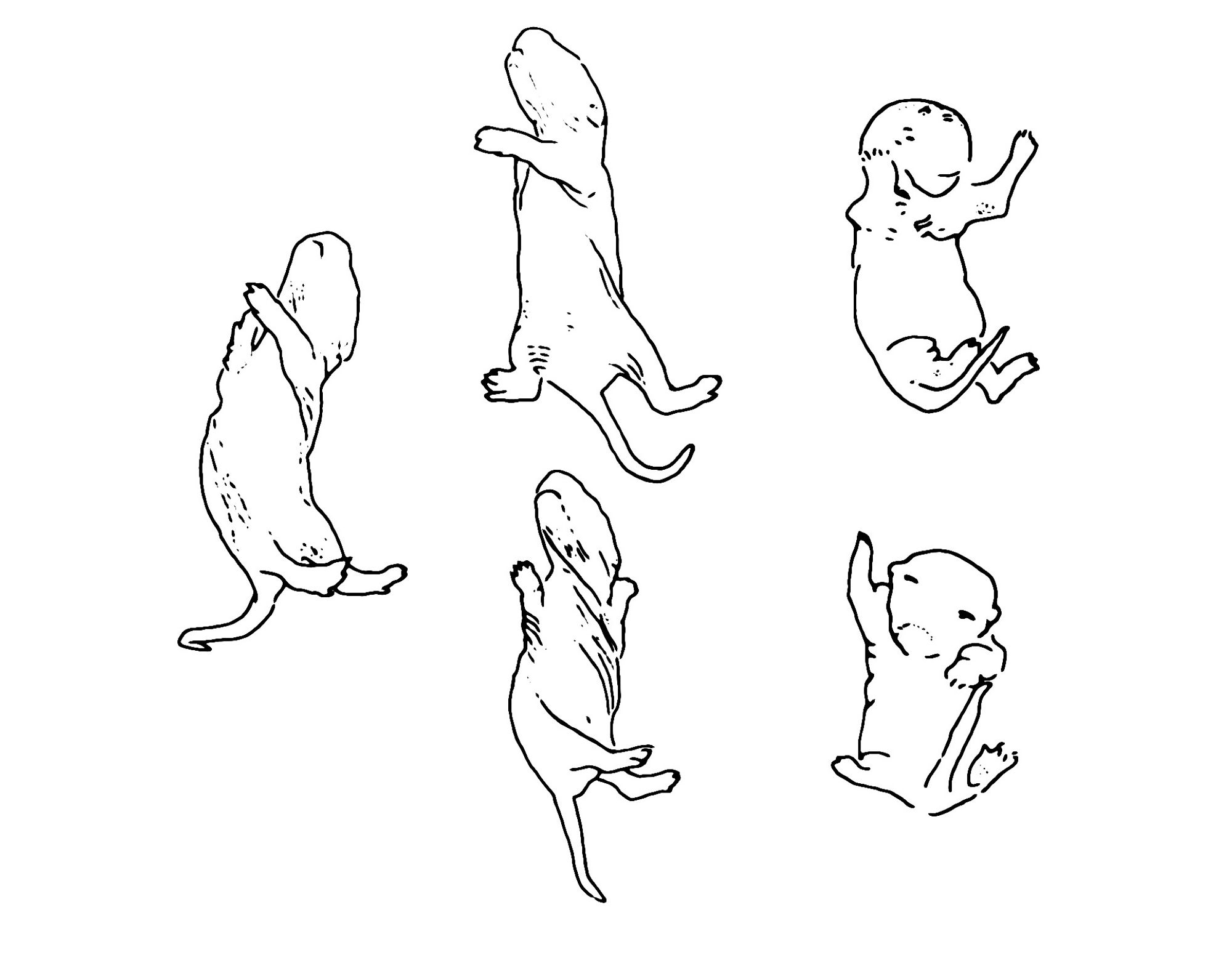

Line drawing illustrating movement categories in surface-righting tests.

Courtesy of Jeffrey Alberts and NASATheir heightened response to angular motion traced back to their mothers, who had rolled around and climbed walls and ceilings in microgravity. The fetuses experienced these movements in utero, during a critical phase of vestibular development, leaving them adapted to a world in which the ground was not the limit. This showed in their neurons too. In the absence of gravity, cells in the semicircular canals of the inner ear—key to sensing angular acceleration—formed stronger connections in the brain. Meanwhile, gravity-sensing neurons reached the brain but formed fewer synapses, consistent with the core principle of brain development that stimulation determines maturation.

When space changed how the mothers behaved, it also changed how their fetuses developed. Alberts now predicts that growing up entirely in space will rewire the sensorimotor system of any mammal. And it was after that first Kosmos flight, as he wrapped up his experiments with Serova in Moscow, that Alberts began to consider the full implications of humans living away from Earth's gravitational influence.

*

Alberts concluded his experiments in Russia in early 1984. The scientists had seemingly overcome every logistical and political hurdle. But as Alberts stayed to wrap up his experiments and ship back his equipment, the NASA crew decided to return home for the holidays. “At the time, you didn’t do this—you didn’t leave somebody alone in Moscow,” Alberts explained. “But they did, and then things started to go bad for me.”

A message came through Serova, offering no explanation, that Alberts was prohibited from taking the data back to America. Alberts was livid. After several failed attempts to convince the Soviet officials, he went to the American consulate in Moscow for help. Together, they devised a scheme. The consulate arranged for Alberts to call an American journalist from his hotel room. The journalist, who was in on the plan, would agree to run a story about the Soviets refusing to hand over the data, in violation of their international agreement with the United States. The assumption was that Alberts’s phone was bugged, and the call would serve as a warning—to whoever was listening in—to release his data, or the Soviet Union would be disgraced in the press.

Alberts can’t say for sure that anyone was listening, but shortly afterwards, the Russians agreed to release the data. The Institute of Biomedical Problems organized a symposium to mark the end of their collaboration and formally hand over the data disks.

The Soviets were big on ceremony, and Alberts knew that this would involve toasts, speeches, and the exchange of token gifts. He arrived at the Institute with his bags packed and his farewell gifts ready, but found that the meeting had been postponed by a few hours. As Alberts wandered the halls to kill time, he happened to reach into his backpack and discovered a handful of seashells from a recent visit to his parents in Florida. On a whim, he added the shells to his collection of gifts.

“I gave these shells to Luba,” Alberts told me. “They were very beautiful, and she just disappeared. She just floated before my eyes into some other sphere.” Serova held the shells up to her ears, gazing into the distance. Bewildered, Alberts turned to the interpreter assigned to the project, who had become a friend of his, and was also close with Serova. “You may not know this,” the interpreter said, leaning over, “but Luba believes in reincarnation—and she thinks she was a mollusk in her previous life.”

*

It’s hard to overstate the impact of the Bion program. More than 100 U.S. experiments were conducted on the Kosmos flights, resulting in over 200 publications. Hundreds of researchers, engineers, and students across several countries owe their training, some of them entire careers, to the Bion program. Their collective expertise has become a vital resource, not just for national space agencies but also for the International Space Station—which has carried forward this spirit of global cooperation.

The ISS, which was launched in 1998, includes both American and Russian orbital segments and is jointly operated by the United States, Russia, Europe, Japan, and Canada. The station has hosted astronauts from 23 nations. It ranks among the most ambitious international collaborations ever undertaken. But this era is coming to an end: the ISS is scheduled to be deorbited and sunk into a remote part of the Pacific Ocean in early 2031. Political tensions between the United States and Russia have been cited as one reason for the station's retirement—with Russia announcing its decision to quit and build its own orbiting outpost. China, one of the few countries to be excluded from the ISS, launched its own station in 2021. In the United States, private companies are set to usher in a new era of commercial space stations. And in a gesture rife with symbolism, NASA has handed SpaceX the task of delivering the ISS to its watery grave in the Pacific.

We have already ceded our rockets and space stations to men with messiah complexes—and our wombs may be next. Elon Musk aims to shuttle a million people to Mars in the next 20 to 30 years. If we are truly committed to becoming a multi-planetary species, there’s serious danger in entrusting that mission to billionaires and private space companies, or to the strategic agendas of competing nations. Migrating to Mars would be one of the most complex and perilous endeavors in human history. It will require more global cooperation than ever before—not less.

It will also require understanding what space might do to women and children.

Of the 693 people who’ve been to space, only 105 have been women—and that number includes tourists like Lauren Sanchez and Katy Perry. Among the female astronauts who have undertaken long-duration missions, most chose to suppress their menstrual cycles for practical reasons like limited water, waste management challenges, cargo constraints, and personal comfort. We don’t even know how many women have had their period in space, and the number is undoubtedly small.

The only empirical data on pregnancy in space come from Jeffrey Alberts’s studies of rats, the last of whom were sent into orbit in 1995—three decades ago. And Alberts’s findings serve as a warning: Even partial exposure to microgravity during the latter half of a rat’s pregnancy made labor more difficult for the mother and altered vestibular function—affecting both the brain and behavior—of the fetus. It’s reasonable to hypothesize that humans would experience similar, and likely far more extreme, changes if a pregnancy began and ended in space.

Human pregnancies move through a series of biological phases, each building on the last, and finely tuned to the Earth’s environment. The effects of microgravity—and other challenges like space radiation—will vary at every stage: from the earliest moments, when a child is just a cluster of cells; to the placenta forming and linking the life-support systems of mother and child; to the embryo building organs and limbs; to the fetus developing movements and senses molded by its mother’s behavior; to labor and birth. After birth, simple acts like breastfeeding and cradling a child will become more challenging. Even the slightest shift could ripple outward, altering—or ending—the lives of mother and child.

Pregnancy is a period of exceptional vulnerability. Both mother and developing fetus undergo dramatic changes that increase their susceptibility to environmental stressors—far above what healthy non-pregnant adults typically experience. Women who board Musk's Starship should not expect to survive giving birth on the Red Planet. Right now, we simply don't know enough about what will happen to pregnant humans in space—let alone how to keep them alive. And beyond pregnancy risks, infertility for Martian settlers of all genders is likely to be a serious problem.

No human has ever had sex in space, according to NASA—and given the agency's notoriously prudish stance on such matters, no astronaut has said otherwise. We might have learned something about the mechanics from PornHub after the site attempted, in 2015, to crowdfund the first zero-G sex tape.“ We will not only be changing the face of the adult industry,” said the company in a statement. “We will also be chronicling how a core component of human life operates while in orbit.” Sadly, for both the adult industry and for science, their campaign failed to raise enough money. My bet is on human ingenuity, but given all the physiological changes—like the upward shift of fluids in microgravity—sex in the 100-mile-high club could be arduous and unpleasant.

Exterior view of a Bernal space colony concept, 1970s.

Courtesy of NASA/Ames Research CenterMany astronauts report a decrease in libido during spaceflight. Male astronauts have generally reported normal function, but a recent NASA-funded study found that cosmic rays—and, to a lesser extent, microgravity—could increase the risk of erectile dysfunction among space travelers. Deflating news, to say the least. What’s more, a woman’s supply of healthy eggs could shrink by as much as 50 percent, and menopause might happen earlier on Mars because of radiation. Men could also have lower sperm counts and poorer sperm quality.

If a few brave souls still choose to make a Martian journey, they can’t come from just one nation, race, religion, class, or culture (and no matter how many children he fathers, Elon Musk alone can’t populate a planet). If we’re to have any hope of thriving off-Earth, we’ll have to let go of artificial boundaries in favor of true diversity. A diverse founding population will be better able to adapt and evolve on Mars, and have a better chance of developing new solutions for survival, giving natural selection more variety to work with. And we would do well, in this vein, to not limit ourselves to current space-faring nations. The greatest range of human genetic and physical variation is found in Africa. The birthplace of humanity may also hold the key to our future in space.

Surviving Mars will require a complete reinvention of how we live—from the habitats we build and the clothes we wear, to the way we grow food, treat illness, manage waste, raise children, and govern ourselves. Whatever we build will call on the full range of human diversity and ingenuity—and it will, inescapably, influence the evolutionary forces that act upon us.

Suppose we do survive, and our space-born babies grow into adults. They fall in love—or more likely, enter a breeding program aimed at selecting for space-adapted traits, one that would please the Bene Gesserit of Dune—and have children of their own. After many generations in space, their human brains, bodies, and behaviors will be transformed. Growing up away from Earth won’t just rewire the vestibular system, as Alberts observed. It will reshape their every sense: how they feel, smell, taste, and see. Their limbs may atrophy from underuse. Their speech may shift, too—on Earth, our jaws open with gravity, so the lower jaw muscles have to work to keep our mouth shut; in space, humans may lose some of those muscles. As NASA’s Emily Morey-Holton puts it, “E.T. may be a good example of a species evolving at a lower gravity field—with a rotund body, duck-like flappers for feet, minimal legs, long thin arms and fingers, and a large head, large eyes, and minimal hair.” Our space-born descendants may no longer be sapiens.

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.

Courtesy of PixabayIf Musk masterminds a city on Mars, or Bezos pours his fortune into an O’Neill Cylinder, they won’t just be building the first human settlements beyond Earth—they will be creating the conditions that determine the future evolution of our species. And inevitably, they'll wield extraordinary power over the most vulnerable participants in this grand experiment: the women whose pregnancies will become laboratories for humanity. Our Martian migrants must be told, in full, what they are signing up for. And perhaps the most sobering fact of all is that even success will come at a cost. Each generation developing in space will become more adapted to that environment, and evolution across multiple generations may change us irreversibly.

“We may find that if you grow up in space,” says Jeffrey Alberts, “it’s best that you stay there for the rest of your life.” If we boldly go where no man has gone before, it’s likely we will never return.

Yet, many of us will remain captivated by space—by Star Trek, Star Wars, Star Maker, 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Dispossessed, Major Tom. I could go on. But the truth is that becoming a multi-planetary species will be anything but romantic. It will be hard, dangerous, and gruesome. And if we hope for even the slightest chance at success, we’ll have to face our deepest divides, protect the most vulnerable with everything we’ve got, and work together like never before. Because in the end, space will change us, but it will not save us. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast