What Kind of Clam Are You?

Robinet Testard, Marvels of the World, 1480-1485.

Courtesy of Bibliotheque Nationale de FranceMost visitors in the dim room on the first floor of the American Museum of Natural History are there to look at the 21,000-pound fluorescent blue whale model suspended from the ceiling, but when the writer Anelise Chen and I visited in October, she headed straight for the walls lined with smaller crustaceous creatures. “That one is probably a nautilus,” she said, pointing at a sinuous shape sitting inside a display case. “And that one’s the clam.” There were other animal specimens she couldn’t identify: small pinkish shells, smooth beige shells, bumpy shells, shells with spiky edges, shells whose swirls resembled the tops of cinnamon rolls. Shrouded in the pale yellow light of the museum display, some of these shapes looked entirely out of place, somehow not belonging in the same world as the French tourists standing behind us, the carpet beneath our feet. Others, however, like the clam, looked entirely mundane. “Isn’t it crazy that this is from 70 million years ago and it’s still recognizable to us?” Chen said.

Chen had never given much thought to these creatures, until one afternoon in 2016, when, recently divorced, she received a text from her mother warning her not to be too dramatic after crashing her bike. The accident had been caused by “momentary inattentiveness and conditions of reduced visibility (sobbing while cycling).” “Clam down,” the message read. Clam down, she thought to herself. Her mother had, of course, meant to say, “Calm down.” She’d made the same typo before. But Chen took her advice to heart as written: she began to wonder what life would look like if she metamorphosed into a mollusk. “At the time, I didn’t know anything about them at all and just imagined myself in this clam outfit with my legs sticking out,” Chen told me, crossing her arms in a knitted sweater that bunched around her shoulders. “In my first Google searches, I was just trying to figure out basic things: Are they alive? Are they happy?”

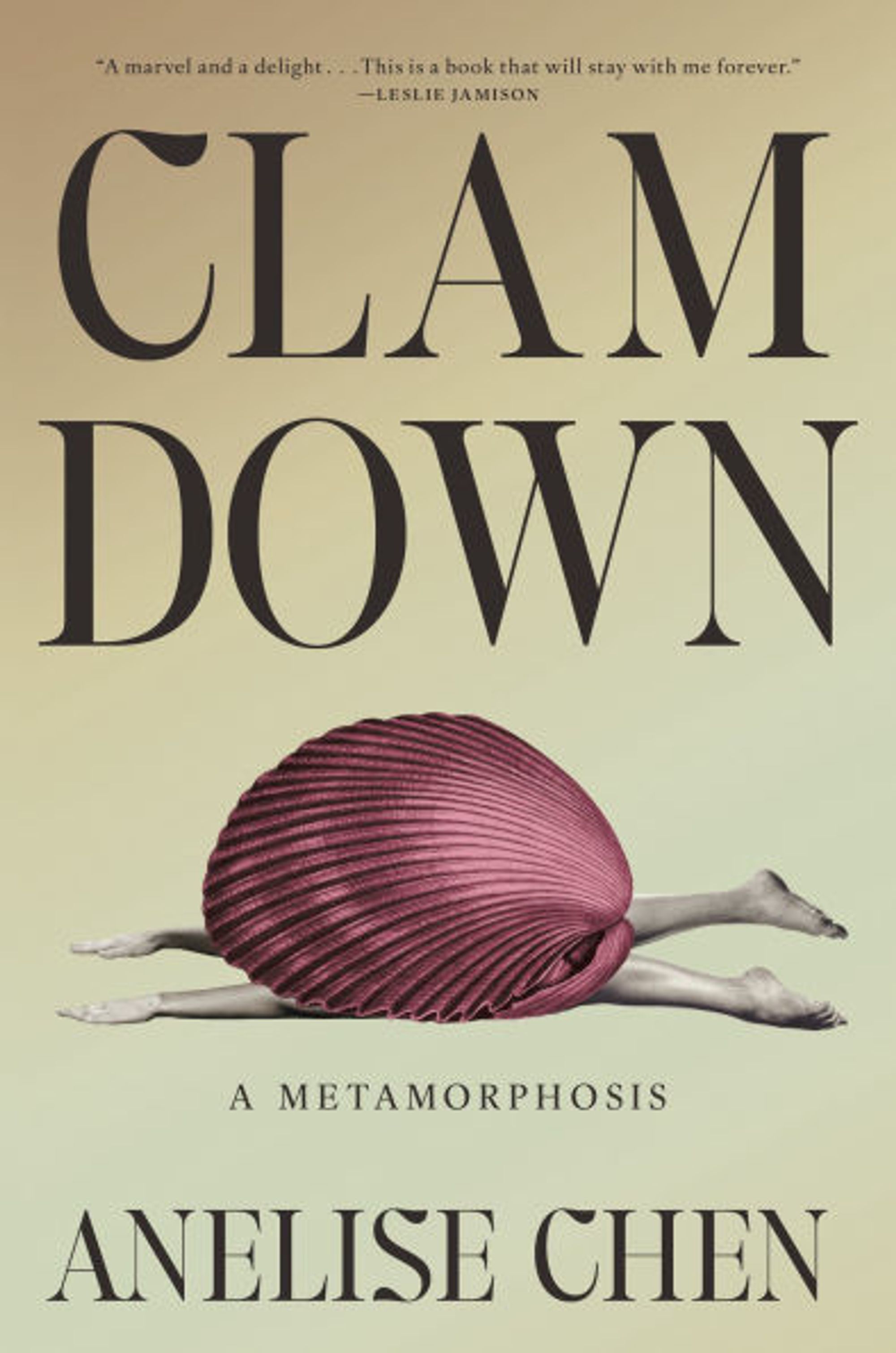

Her new book, Clam Down, is a memoir written in the “third-person clam.” Chen’s first novel, So Many Olympic Exertions, combined elements of sports writing and memoir in a style resembling hypomnemata, the ancient Greek form that coaxes narrative out of a writer’s “notes to the self.” With its Kafkaesque premise and various shifts in perspective, Clam Down takes this genre-bending tradition a step further.

Mollusks burrow. They create shells around themselves. They hide. And sometimes, people do too. Chen writes about the pleasures and perils of a life spent inward, but her aperture is never narrow. She mines stories from the worlds of art, science, and literature to consider why people retreat during challenging times, consulting the likes of Charles Darwin, Italo Calvino, Georgia O’Keefe, Agnes Martin, and others. As she connects the dots of her clam genealogy, her shell seems to open, little by little. “These survival strategies that we learn to cope with pain, it’s not like we just invent them,” she said. “They’re passed down to us.” Chen’s book reframes withdrawal not as escape, but as a kind of inheritance—a way of making sense and safety in an often inscrutable and dividing world—and as the main necessity for creating art. The challenge is turning reclusion into revelation without letting hiding become habit. How do you build a shell that protects without trapping you, cut off from others, inside its walls?

As it turns out, Chen’s crustacean roots run even closer to home. Her family moved to California from Taiwan when she was young, and her father spent her childhood in a self-imposed exile, going back and forth between the two. First, he left to create a mysterious software package aptly named Shell Computing, and later he finished a PhD program in digital learning. In Clam Down, Chen attempts to understand the effect his prolonged absences had on her. “I started looking at my parents and realized I was not the original clam,” she writes, recognizing their tendency to shut down during conflict as a defensive mechanism against racism, xenophobia, and more general alienation. “In fact, they are clams too and they have all these clam-like coping mechanisms because they’re immigrants.” Shifting between her parents’ perspectives, Chen moves in and out of the rhythms of their accented English. She pays careful attention to the linguistic and cultural barriers between people to illuminate the miscommunications inevitable to spoken word. These observations poke fun at the comforting, if misguided, illusion that we can grasp the full extent of what others are trying to tell us. “Human communication was a farce,” she writes in Clam Down, after trying and failing to find the words to say to a man she thought she was in love with. Yet, rather than abandoning language altogether, she gathers all of her own clammed-up misinterpretations and experiments with form and voice to write her way toward the spiraling question—and in this pursuit, she skirts her own “I.”

Chen is far from the first writer to use the third person to talk about herself. J.M. Coetzee’s memoir Boyhood comes to mind, as does Salmon Rushdie’s Joseph Anton. Unlike Rushdie and Coetzee, however, Chen also makes use of the first person in Clam Down, occasionally writing in her mother’s and father’s voices, but never her own. Glitches in communication appear most salient with her parents. “Why must we fight every time we see each other?” Her father asks at one point in the book. “What did I say wrong? Why, when I am only trying to prevent the suffering I experienced, do my children say I am the one hurting them?” Here, he seems to reach across the generational and cultural chasm, where intention and interpretation seldom align. Yet despite this room for error, Clam Down prioritizes the relational self, and ultimately hints at the idea that it is very hard to understand oneself separate from the encounter with others.

This anxiety-producing tug between looking inward and looking outward is a conflict central to Clam Down. “The question again. To speak or not to speak?” Chen asks. “Her research rectified a misconception. As a child, she mistakenly believed that the clams that stayed shut even after their counterparts had been steamed to death were the ones worthy of emulation. In fact, those were the dead ones, the ones you were supposed to throw away. She did not know, not then, that clams spend much of their lives with their mouths slightly ajar, like undersea mouth breathers.” Like humans, they need to open their mouths to live.

On the C train home from the museum that day, I began to see everything and everyone as clam-like: the women crossing their legs, the men wearing headphones, all of us curving into ourselves, hunching over our phones, cut off from the rest of the world in a tubular vessel some 100 feet underground. Here we were enclosed from the world, exposed to each other. We looked like the dancers in Martha Graham’s Oedipus, contorting and curling our spines into crescent shapes, folding inward. Like shells, we sealed ourselves off, disappearing our soft parts to protect them.

The train sped into the dark, grumbling as it slid along the tracks, and I listened in the same way I’d listen to the coming and going of the ocean, or the oscillations inside a seashell pressed against the ear. At the museum, Chen and I had talked about the sound and I’d mentioned Joni Mitchell’s “Blue,” which describes this strange hum.

A shell’s echo suggests something like movement, presence, but to hear it you have to listen alone. Only one ear can enter the spiral at a time, and it must be enclosed within the shell’s opening, enveloped in its curves and undulations, to hear anything at all. Chen writes from a similar place of solitude, with an ear ever-held to the opening of experience. Her approach isn’t isolation for isolation’s sake. It’s a better way to listen. And that’s what allows her shell to become less a shield than an archive: a container for memory and meaning. I hadn’t remembered Joni’s lyrics at the time, but in that moment her line returned to me in its entirety:

“She calls that noise a ‘sigh, a foggy lullaby,’” I wrote Chen in an email, then slipped my phone inside my bag and waited for my stop.

Peter van der Heyden, The Shell Floating on the Water, 1562.

Courtesy of Saint Louis Art Museum*

A few weeks later, I visited Chen’s apartment: a bright, airy space she shares with her husband, a horticulturalist, and their toddler, Henry, in New Haven. That afternoon, the dining room table was covered in a blanket of crumbs, the living room couch in toys and drawings. Warm orange rays shone through the windows, carving soft shadows around the room. Henry was sitting in his booster seat, learning how to crush apple slices with his hands to create a sticky, mushy paste. “Juice!” he proclaimed, clearly delighted, his fingers shiny. “Juice!” Chen stood off to the side, grinning as her child learned to speak through touch and taste and mess.

Chen has a knack for putting the banal in its proper context, treating the histories of inanimate objects as seriously as she does the biographies of human beings. People carry baggage and history, but so do clothes and cobblestones, rocks and shells. Objects, too, keep time and witness, perhaps more diligently than we can. In his essay “Always Returning,” Teju Cole learns from a colleague that the writer W.G. Sebald always wore two watches, one on each wrist. “Was it something to do with the mystical properties of different metals? Was it some strange sense of time that demanded simultaneous witness?” he writes. “Or was it simply [his] dry sense of humor? And were the watches even set to the same time zone, or was one testifying to past time, the way his writing did?”

Chen writes like she owns a second watch. Clam Down may not sit in an atemporal space, but it still weaves together multiple chronological threads. And her sentences, like Sebald’s, take on a meandering form. She glides between past, present, and future as though to ask: What if? What then? What now?

“Every decision you make has a lasting consequence, think about that, she thought as she walked down the narrow alleys shadowed by stark rows of Haussmann-era buildings,” Chen writes in Clam Down, recalling a trip to France. “The buildings were made of Lutetian limestone, the stone that built Paris, quarried right here since Roman times.” It dawned on her that these materials had undergone 40 million years of sedimentation and pressure. “Excised from the subterranean depths and lifted up to the surface, Paris forced you to look at all this memory in the eye, at street-level,” she continues. “That was why she couldn’t stop remembering.”

*

One Sunday in late October, Chen and I walked up East Rock in New Haven, a wrinkly, red-faced ridge that overlooks the city. She takes this walk every day, usually around 4:00 in the afternoon when she’s too tired to keep thinking. That day the ground felt dry and crumbly, the atmosphere hazy. It had scarcely rained that October and we could both feel it in the thinness of the dusty air. On the way up, we passed people walking in athleisure and small birds and parents with toddlers in tow. Chen and I didn’t make eye contact as we walked, our conversation taking on a more natural, less structured form. By the time we reached the top, I had nearly forgotten where we were going.

“What would you be if you were at this spot 22,000 years ago?” asked a sign on the summit ledge near a pile of dried autumn leaves. “From evidence that you can see at many places in East Rock Park,” it continues, “the answer is cold, VERY cold—you would be buried under a half-mile of ice.” The rocks one sees today appeared only after the ice melted away, exposing layers of sediment. On the way down, we stopped to look at the skeletons of beech trees on the other side of the city’s Mill River. Their branches and trunks were sad, barren, and greyish on account of the microscopic parasite that has been ravaging Connecticut’s forests for years now. Chen doesn’t know why they haven’t been chopped down yet, though she is glad they’re still there. She told me that the word beech and book have the same root because people used to write on tree bark, then corrected herself: “used to” is probably the wrong thing to say. “Just look at the graffiti on the trees,” she clarified, pointing at the white clouds of spray paint decorating their trunks—to say nothing of where paper comes from.

A few months after Chen and I met in New Haven, I was back in New York when I walked past a lumpy boulder, 30 feet high, sandwiched between two apartment buildings in Morningside Heights. The rock was locked up behind an iron fence, its surface smooth, black, and rain-soaked. A scrawny branch sprouted from one of its many grooves. Later that day, I found out that this boulder, part of the city’s ancient bedrock, is nearly 450 million years old. I started thinking about time again. The rock pointed to something truer in the landscape, and suddenly it seemed more genuine than the surrounding man-made buildings. Both rocks and shells are made of minerals; both have seen and touched more than most of us ever will in our lifetimes. “The mind reaches for geologic metaphor when thinking of generations,” Chen writes in Clam Down. “Misery was sedimentary matter. Layer upon layer of accumulation. Uplift, erosion, compression. Each generation minutely altered, living, dying, and drifting down to build upon the faults of the old.”

Clam Down: A Metamorphosis (One World, 2025).

There’s a moment in an Italo Calvino story when the narrator—a mollusk marooned on a rock somewhere—states that it wanted to make something that would mark its presence in the world. “So I began to make the first thing that occurred to me,” Calvino wrote, “and that was a shell.” Chen crafts Clam Down as that mollusk instructs. She peers out from her self-made enclosure at the sprawl of time, text, and space, twisting together fragments from within and beyond her. Estranged from her own story and species, she writes with the perspective, humor, and armor that distance provides. Back in the museum, Chen said that “in the moment of building, or making, you have no idea what you’re creating—you’re just in the mud, in the dark, but by the end of it all you end up with this beautiful, twisty form you can display.”

In this way, books are a kind of sedimentary process, a sort of shell-building, formations of thought and time that we slip into, grow within, and eventually shed. Chen told me her deepest satisfaction comes from seeing the spiral completed, the form made whole and ready for others to inhabit. “Absenting myself from the shell,” she called it. “And letting others come in and experience it for themselves.” ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast