The Reverend Is Saved!

It’s a 40-minute drive to Kristin Hayter’s home in New England from the train station where she picks me up, and as we near her idyllic town, a road sign advertises “SATAN’S KINGDOM.” The sign, improbably, marks a local recreational site. But it seems heaven-sent from the world Hayter has created in her experimental music as Lingua Ignota: Satan has been a recurring figure in her blazing amalgam of metal, opera, noise, industrial, and baroque grandeur. From the passenger seat of Hayter’s Jeep, I scream my surprise. “SATAN’S KINGDOM?” She laughs dryly. “That’s when I knew I had to move here.”

Hayter recently retired her Lingua Ignota moniker, under which she recorded her first three incendiary full-lengths beginning in 2017. She’s now rechristened herself the Reverend Kristin Michael Hayter to embrace a conceptual new chapter. On this Thursday afternoon in September, Hayter wears a lemon yellow sweater, her blonde hair middle-parted to a low bun, with a Prada bag slung across her chest. She had in fact never been to the semi-rural community where she lives before becoming “obsessed with getting a derelict Victorian home to restore.” After finding the Gothic Revival of her dreams, she arrived here last year knowing no one, looking to start over.

The infernal music of Lingua Ignota mixed blood-curdling death growls with mellifluous melodies; liturgical drama with feminist revenge; rawness with virtuosity; brutality with overwhelming beauty. Though Hayter began vocal lessons as a child in San Diego—also the hometown of her clearest artistic predecessor, Diamanda Galás—she did not conceive of herself as an artist until she arrived in Providence, Rhode Island, for grad school. She earned an MFA from Brown’s Literary Arts program in 2016, where her ten thousand-page thesis “Burn Everything” took the form of a song cycle based on Igor Stravinsky, also using text appropriated from “subgenres of extreme music that mythologize misogyny” and court documents from her own domestic violence case. It gave birth to Lingua Ignota, the artistic persona that became an unplaceable outlet for her trauma as a survivor. Though Lingua Ignota first found an audience in DIY noise, experimental, and metal circles, Hayter owns her scholarly roots; she calls her work intensely “research-based.” As an undergrad studying writing, her academic work connected the regimentation of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier to anorexia (a disease she said “ran my life for 13 years”).

Her prodigious second LP as Lingua Ignota, Caligula, in 2019, was a breakthrough that scaled her audience; a piece of embroidered fan art at her home bears the forbidding benevolence of her lyric, “ABANDON YOUR BODY SO NO MAN CAN BREAK IT.” Her next and, ultimately, final Lingua record, 2021’s Sinner Get Ready, amplified her musicality with Appalachian folk instruments—she called its gently menacing balladry “rural horror”—and lost no severity. While composing it, however, Hayter found herself isolated in Pennsylvania and in another abusive relationship. Her new record, Saved!, is the first she’s recorded as an ordained Reverend and an extension of her efforts to tangibly heal; released in October via her newly founded record label Perpetual Flame Ministries, it moves away from themes of abuse. Saved! is a concept album in which Hayter assumes the character of a salvation-seeking Christian preacher, delivering decayed and warbled folk, augmented hymns, tape manipulation, and purgation tales for her most allegorical project yet.

When she’s not making high-concept avant-garde music and co-running her label, Hayter’s current hobbies include watching The Bachelor (“an anthropological interest”) and riding her dark bay horse, Coco. “I’m horse crazy now,” she says of this therapeutic love reclaimed from childhood. She has also been devoting ample time to restoring her 150-year-old house, which she shares with her tattoo artist boyfriend, who greets us politely mid-interview in one of two light-filled parlors.

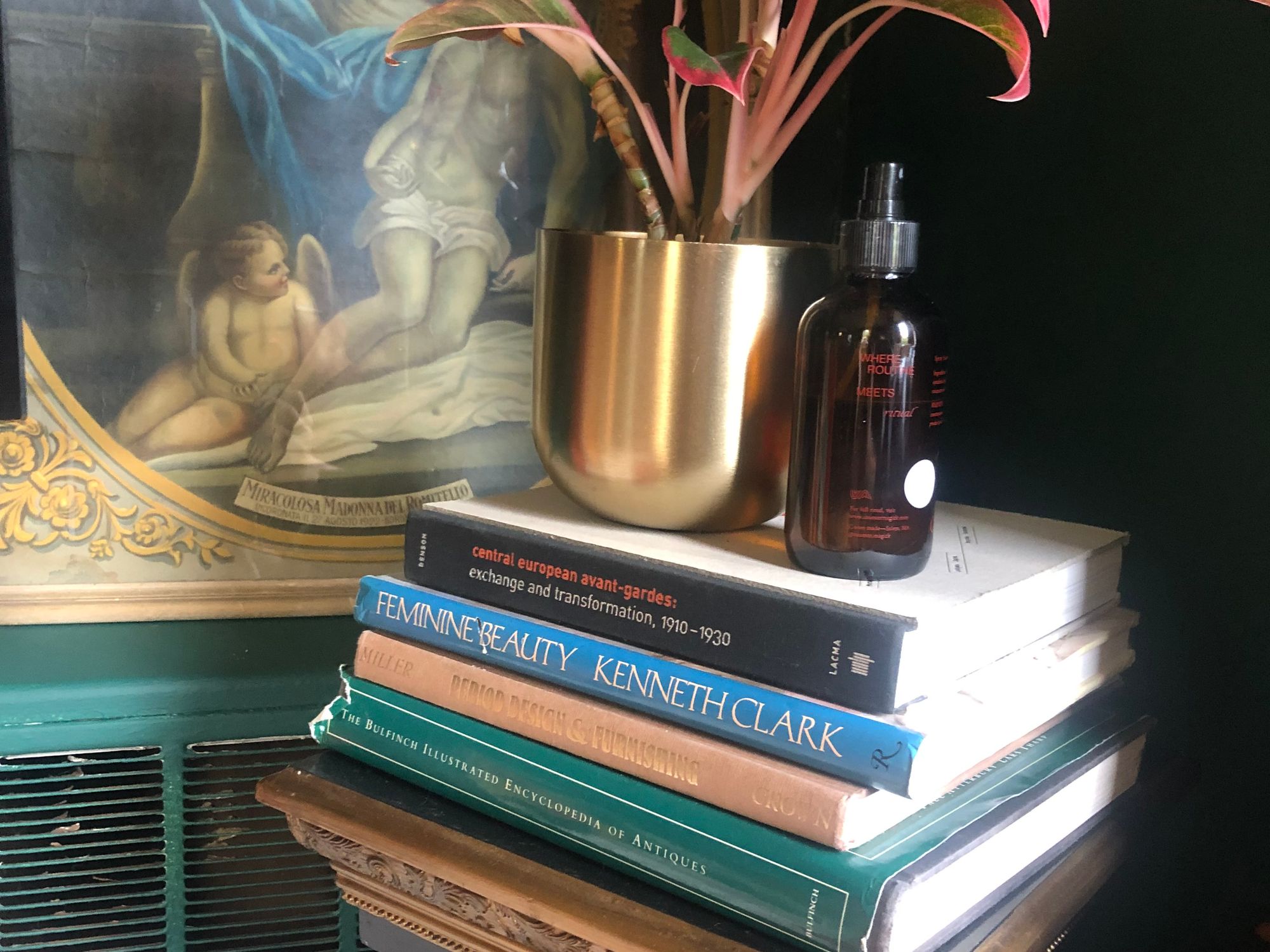

The satanic road signage has nothing on Hayter’s occultish oasis of a home. Throughout the ground floor, antique pump organs and ornately carved mantels hold religious relics, brass candelabras, oddities, and flowers. The house’s original woodwork includes carved medallions depicting the likes of Beethoven and Shakespeare; a chandelier hangs above the piano. Thrifted paintings abound. A Hank Williams record and Rite of Spring sheet music are on display, and lining the bookcases are Sartre, Beckett, Chekhov, Artaud, Baudrillard. Among the art books sitting in view are Feminine Beauty and Central European Avant-Gardes: Exchange and Transformation, 1910-1930. A heavy ecclesiastical vibe runs through the house’s very scent, laced with a fragrant spray Hayter mixed of cedarwood, pine, and cloves.

Down in her spider-filled basement, she shows me a six-foot tombstone she found there, a few months after moving in, for the father-in-law of the man who built the house. She directs me through catacombs-like corridors towards a space where, atop a mountain of coal, she constructed a floral installation for the cover of her new album. “It was supposed to be like an earthly paradise,” she says. “I was trying to create a Garden of Eden, but also vile and chintzy.” We spend the next three hours talking about her journey through and beyond Lingua Ignota. Before Hayter drives me back to the train, she takes me next door to the tiny episcopal church on her property. She sometimes plays the organ alone there after midnight, she tells me, before unleashing its imposing, divine drone.

Do you still consider yourself a noise musician?

I don’t think I ever really considered myself to be anything. I’ve always been most interested in the limits of language, whether it’s a musical language or a written language. I feel like noise is at the limits of music, or plays with that. My interest has always been in prodding at what the limits of a certain genre are, as opposed to trying to fit into any one in particular. I never really felt at home in the noise community or the metal scene. I have very much always approached things as an outsider, but I do feel that this new record is noise in a way. There’s no noise on it really, but it has the ethos of a noise record.

How are you feeling right now amid retiring an old identity and forging a new one?

It’s been a welcome experience. After Sinner Get Ready came out, and everything that came along with that, I was like, “I’m never going to make music again. I’m done.” And I felt that way for quite a while. Then I thought, “Maybe I can keep going and do something else.” Doing Lingy no longer felt right. I was more interested in this religious conversion stuff and the apocalypse of the self and all that.

It has been nice to no longer engage with themes of abuse and to just focus on doing fun stuff with the music, which has not been a part of my career so far. I feel good about performing in the future as opposed to completely dreading it. But if this ends up not feeling good for me for any reason, I think I could be musically fulfilled just singing to myself in the church next door.

From the beginning, you described the music of Lingua Ignota as painful, but was there a point at which you realized, “I can't do this anymore. This is not sustainable”?

A big part of my personal pathology is feeling like I don’t have value as a human being; I have value for what I do. When I started doing Lingua, all of a sudden it was like, “Oh, this has value for people.” It was a cipher for my experience, but it was not about me necessarily. At the same time, I was so miserable as a person and wasn’t actually healing.

So I got stuck over and over and over again. At a certain point, I started actually trying to heal in tangible ways, working really closely with a therapist and doing all the fucking shit. I was trying to accept myself as a person, and become a person that I liked outside of things that I accomplished. I realized then that I had to let go of Lingy, and let go of all that stuff.

I didn’t realize how painful it was at the time that I was making it, and I didn’t understand that I was in so much pain. I was really numbed out. In retrospect, I can’t believe that it happened. I can’t believe I was in so much pain that this music exists.

What were you like as a teenager?

I was a goth. I looked so stupid. Everything was mesh with the finger holes and just brutal. I never felt like I belonged anywhere. I also had really bad body image issues that got progressively worse over time. I got bullied a lot by the popular girls, and so I was like, “I refuse to participate in this society.”

One of my first shows was Converge at the Ché Café in San Diego. I was really into seeing classical music and I was doing classical recitals, but I was super shy and I didn’t love attention. I was also really into visual art, so I went to SAIC and from there I started doing multidisciplinary work.

Did anything from that time prime you for an interest in extreme music?

I was always interested in medieval music, which for classical is kind of extreme, or has an extreme set of constraints. My friends and I were into Ornette Coleman; we would get together and do weird jazz improv. And I was a huge Nine Inch Nails head, even though my friends frowned on me for that; they were like, “He’s too mainstream, we have to listen to only late Miles Davis and obscure math rock.”

You’ve referred to Lingua Ignota as an allegorical project, and your undergraduate degree is in writing. What has your relationship to language and storytelling been?

I got into school on a painting scholarship and I stopped painting almost immediately. Instead I got into art history and moved into studying language as an art form. I never thought I was a good writer per se, but I could take other people’s language and do interesting stuff with it. I became interested in telling stories in a procedural way with severe constraints. I was looking at formal poetry and stuff like the Oulipo movement and pataphysics and stuff that really takes risks with language, like Georges Perec’s A Void, which is written in French but does not have the letter e in it. And there’s a book called Eunoia by Christian Bök, where each chapter only has one vowel in it—almost like early algorithmic, patternistic ways of thinking about how to arrange language. That stuff was really fascinating to me, and you could almost always work with source material to achieve that. Hence working with Bach instead of writing my own music. That carried over into everything I did with Lingua as well.

Once you got to grad school, how did you envision yourself as an artist?

I never necessarily aspired to be a practicing musician. When I was graduating from Brown, I was performing some Lingua stuff at the end, but I had also applied to a PhD program at Brown. I always planned to go into academia and to do scholarly research. And a lot of my practice is kind of scholarly. There’s a lot of research and crap. Transcribing that into DIY spaces and into punk spaces was interesting, but I never really felt like I made sense in either world.

Your Brown thesis, which was the foundation of Lingua, was extremely provocative and included material about women who kill their abusers. What was the institutional response like from people in academia?

The thesis for Lingua came from algorithmically generated, preexisting work that was taken from the music that my abuser loved. He listened to a lot of hardcore, black metal, pornogrind, grindcore. I also love some of that music. But I took the language that I heard in there—particularly in the ones that are very into gender-based violence, like pornogrind—and created a huge database of source text. I put that into an algorithm, using Markov chain in orders three and four, and I created my own voice with it. Sometimes I would edit it, sometimes not. It is ultimately not any of my own language really. I was taking that language—which is so loaded, but also so meaningless, just a conceit of the genre—and I was trying to give it meaning again, but obviously in a different way.

So it was very confrontational work. My thesis advisor was always supportive and encouraging, but there were other people who were like, “This is uncomfortable for us to talk about.” People responded to it more in a DIY punk setting, and it felt better to perform for people who could respond.

What moved you to put this material—some of it about serial killer Aileen Warnis, a sex worker who murdered her clients in self-defense—into the music of your first full-length All Bitches Die?

I was in a really bad situation that I got out of halfway through being in school there. I started reading about reactive abuse and survivor abuse. I read this book called When Battered Women Kill, and then I started reading a lot about Aileen. She was an extremely tragic person who was failed in every conceivable way, and then did fight back against attackers and was executed for it. She became somebody who was really important to the ethos of what I was doing, of trying to create this manifestation of what it is like for women who are being destroyed, trying to create a very different narrative than the narrative of abuse that we’re often taught about fighting back.

Do you remember the point at which you decided that it would be powerful to create art out of trauma, to represent it and engage with it? Many people who endure abuse just want to move on.

Yeah, I don’t think I really thought it through [laughs], but it felt like the thing that I had to make at that point. I couldn’t make work about anything else. That was what was very recently happening in my life, and I was trying to figure out how to live. I thought making the work was a way of healing and processing it. It was an outlet, in some ways, and it was a way to validate and give voice to things that are silenced so often. But it didn’t help me heal necessarily. It wasn’t actual healing work, but it kept feeling like the urgent thing to do. I never saw Lingua as a thing that would take off. I had no idea that it would be something that I would be continuing to do. I think that was part of it as well.

You were talking about feeling in between the academic world and the DIY world. Your music itself is also a liminal sound, in-between screaming and singing, in-between beauty and the grotesque. It seems like you’ve been making unplaceable music to describe an unspeakable reality. Were these connected for you?

Absolutely. A very intentional part of the process behind making the music was that I needed it to be ineffable, and in some ways indescribable, in as much as the language we have for trauma is not up to snuff, perhaps. Creating these things that couldn’t necessarily be described in easy ways was a huge part and a very intentional part of the practice.

How else would you describe the feeling you were trying to create and inhabit with Lingua?

I wanted to create a space that felt simultaneously incredibly safe and incredibly dangerous, and to create a place where I could talk about my own experiences without actually talking about them—where I could obfuscate them as a way of protecting myself. And to create an intensely antagonizing outsider’s perspective that would perhaps infiltrate these scenes.

The source material was a way for me to say: this comes from an academic place. This all has intention. I am citing all my sources, so you can’t say it isn’t real. You can’t say it never happened. I had talked about my experiences of abusive people and it had been invalidated, so I was creating something that you couldn’t dismiss. Having all of this source material made me feel like I had a bit of a fortress around me. But I also think that it was part of one of my personal trauma responses, which is intellectualizing things.

It’s interesting to hear you refer to the rigor of your ideas as a fortress. There's this sense that in order to be taken seriously, your evidence has to be so concrete. You have to work so hard in order to prove a point. The music itself also feels like a fortress—the maximal nature of it, the technical virtuosity—on a note by note level. But I also think of perfectionism and how that might play into it.

Yeah, absolutely.

On the flip side of that, when Caligula came out, you said you were intentionally trying to make your voice not be beautiful. What does it mean to you to make virtuosic music in pursuit of something other than beauty?

Even though there was a lot of complex stuff going on in the music, it was important for it to feel organic and to feel like it was coming from nowhere. Making my voice uglier is also kind of fighting the socially beautiful feminine voice. There is a relationship between trying to make the voice sound gross and like it's falling apart, and coupling that with technical virtuosity to achieve this very destabilizing effect—again, to exist interstitially or liminally and not adhere to any one thing. Particularly for the voice, error and ugliness are more expressive than something sung beautifully or sung well, a lot of times. It is also to kind of subvert expectations a bit about what women in music should sound like.

This makes me think of your Caligula track “Fragrant Is My Many Flower’d Crown,” where the vocal begins so classically beautiful and by the end is kind of curdled. You sing, “I have learned that all men are brothers and brothers only love each other.” What do you remember about writing that song?

The lyrics are inspired by the Billy Bragg song “Tender Comrade,” which I explored because it was a song that was very important to someone who was really terrible to me. It was a way of reframing my experience of abuse. It was also a bit about my experience of the music industry at the time and the misogyny that is pretty widespread therein. I wanted to juxtapose very heavy, brutal lyrics with these major chords and pretty easy-to-parse piano accompaniment. The voice is a bit of a precursor to the voice heard on Sinner Get Ready. I enjoyed going into extended technique and throat singing for it. I was also trying to thinking about a very feminine non-confrontational song title to contrast some of my others, but then to sneak up on you when you actually listen to the song.

In terms of the Judeo-Christian motifs on Caligula, I remember thinking it felt like you were going to the source of evil, or the source of misogyny, and setting it ablaze. Did you feel like you were going to the source of evil?

I think I was trying to approach an unspeakable evil, and there are sort of antagonists and characters in each album. Creating a very destabilizing environment was part of that, where you don’t know what was going to happen next or how vicious and audacious it was going to get.

It was matter of your circumstance, but Sinner Get Ready was in a lot of ways set in rural Pennsylvania, which sounds like a pretty conservative and extreme place to be living in the depths of 2020. Did being there teach you about the evil you're confronting in the music?

Definitely. Pennsylvania was the site of Sinner Get Ready, and perhaps Pennsylvania is actually the antagonist of Sinner Get Ready. But it became about, again, intellectualizing the trauma and being like, “This is the site of where this is happening, so I’m going to learn everything I can about this place that I hate, that feels evil and awful to me, and that is decrepit and falling apart and lonely and full of people I don’t understand and who don’t understand me.”

I wanted Sinner Get Ready to sound like Pennsylvania, so I did all of this research into the folk music history of Pennsylvania as well as the bounty of religious music from that area. I wanted to create horror in a way that people maybe haven’t heard before. The song “Man is Like a Spring Flower” came from looking at the Pennsylvania Dutch tradition of Fraktur—illuminated manuscripts from 18th century Pennsylvania—and trying to think about how that related to American minimalism, like how to create an Appalachian string band in the style of Steve Reich.

“Pennsylvania Furnace” is such an evocative image; Caligula also felt totally on fire. What are those records burning down?

That has a lot to do with a sense of personal desperation, and transmuting that personal desperation into the musical desperation of like, “Ok, I have to be doing all of these things simultaneously to express this experience, and I will never be able to do it.” It’s weirdly Proustian in a way. Just continuing to try to add and build and research it as much as possible, and the more you build, the more it comes crumbling down, I suppose.

When you look at all of that research, all these crevices of humanity that you’ve explored through this project, what do you feel like it has taught you?

I’ve learned that there is unspeakable evil, but there’s also extraordinary perseverance and extraordinary beauty, and that those things can co-mingle. Even though the tone of the music is often quite absolutist, there is a lot of nuance also that I try to keep, and I can personally acknowledge that there’s a pretty vast spectrum of how those things materialize and manifest. I do think, after all this, it’s tanked my belief in humanity a little bit. I’ve started seeking beauty in other things, and I think that's part of it as well, artistically anyway—trying to look for the beauty in God or in nature.

Within all of this, how do you think your music itself communicates your agenda?

Sometimes in the vocals there’s a tone I take where you’re not quite sure whether I’m being sincere. Like in the song “All of My Friends Are Going to Hell”—the idea of people going to hell, in the Christian right, would be me and people who are actually my friends, trans people, women, Jewish people. But I took that song and turned it into something that says: the people who are actually going to hell are the hypocrites and those who are cruel and do nothing to speak up against inequity. I’m trying to shift the paradigm so the idea of God can be something else for people.

There’s a sort of nasal voice on some of the folkier songs that is a bit bewildering. What is that voice?

On Sinner Get Ready, I started to really lean into the conviction of a folk vocal, listening to a lot of sacred heart music and some glossolalia, not focusing so much on what it sounded like as opposed to what it conveyed within its conviction. There are a quite a few different voices on this new record, which is a bit about a fractured self trying to be made whole. The voices are supposed to be at different stages of the healing process perhaps. I was trying to take the idea of an experimental or avant-garde vocal and flip that a bit. There is an atonality, a tunelessness sometimes; it’s unrefined. It’s noise with no noise.

Have any particular folk records influenced the sound?

I listened to the Louvin Brothers over and over and over again, but I intentionally did not do their perfect harmonies. I was really interested in the angelic, tenor-y, but incredibly angular, sharp vocals there. And then a lot of old ethnomusicological Alan Lomax recordings were really influential in creating the sound of the record and its texture.

On previous records, the fortress you mentioned felt manifested in physical noise filling space; this record is a bit sparer, but there’s still that same fortress of ideas or intellectual fortress.

It’s deceiving in that it’s a little more spartan, but it is doing a very similar thing. It is trying to speak about healing without actually speaking about healing, trying to speak about my experience without actually speaking about it. The themes are different than Lingua, but again, it’s a deeply research-based project. It’s this refusal to be vulnerable and confessional.

At a performance I saw in 2019, you used industrial clamp lights and a sheet to create a really stark silhouette. What have been some performance influences for you?

I used to use clear painter’s tarp and mic stands to create a kind of screen. It was fun to try to renegotiate what the space was. I was thinking about the absurdist theater I’d seen and early Czech theater. Iterations of Beckett as well as Fluxus folks. A little bit of Actionism. So much of the influence comes from film, performance art, writers. I’ve always really liked Bruce Naumann, Ana Mendieta, Judy Chicago. Marina Abramović is a huge influence. When I was doing my grad teaching work at Brown, I taught a course where we kind of replicated Rhythm 0, but in a fully digital way. I love how she makes her body into the locus of emotion and of the art activity or what people impose on her.

Is conceptual art important to you?

Conceptual art is important to the project because I am so focused on the process and how the thing comes together as opposed to necessarily the product itself, and on making the process as much a part of the work as possible. That harkens back to a lot of the procedural writers that I mentioned, and folks like Samuel Beckett, another huge one whom I constantly think of because his characters are created and destroyed by their own language often. The relentless Sisyphean pursuit is a big part of what I’m doing, the fact that I don't think I’ll ever get there.

I’m curious about your fanbase. You have referred to yourself as “Lingy” a bunch of times; did fans coin that? It’s probably hard to decipher, but is there anything specific that you’ve learned about listeners’ relationships to the music?

Lingy was a thing that came about via other people and then I started using it. So I am also part of the mimetic culture around my work, I guess [laughs]. But I like that a lot. I’m not as super serious as people think that I am all the time. As a person, I am 95% attempting to manage absolute terror at all times, and the other 5% is like, goofy goober. I have learned that the weird mimetic stan culture is an expression of love. Somebody actually made Linguini Ignota.

People find ways to engage with you and to be a part of the story. I think that a lot of the people who find resonance in what I do also have a sense of not belonging. I think they pick up on that a lot of times, even if their experiences aren't the same as mine. They pick up on how you can be just as valid existing nowhere and refusing to exist in the parameters that are set forth for you.

Can you tell me about that very extreme glossolalia sample at the end of the new record?

It’s me. It is the act of speaking in tongues, which is a part of the Pentecostal-Holiness Movement’s idea of how one is saved or how one communicates with God. It’s the idea that God delivers language to you that you don’t know and that you can speak, and this is your direct line to God. To try to recreate that, I imposed a lot of restrictions on myself. I fasted and I tried to deprive myself of sleep, and I had Seth blare other people speaking in tongues at me for a very long time. Then I tried to repeat prayer until language went, and it was just brain, muscle, mouth, whatever. I was trying to do it in earnest: “Okay, can I communicate with God? If I were to speak to God, how would I sound?” It was honestly a bit easier than I thought it was going to be, which was a little weird. It really was just letting go of a lot of stuff that was unspeakable. ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast